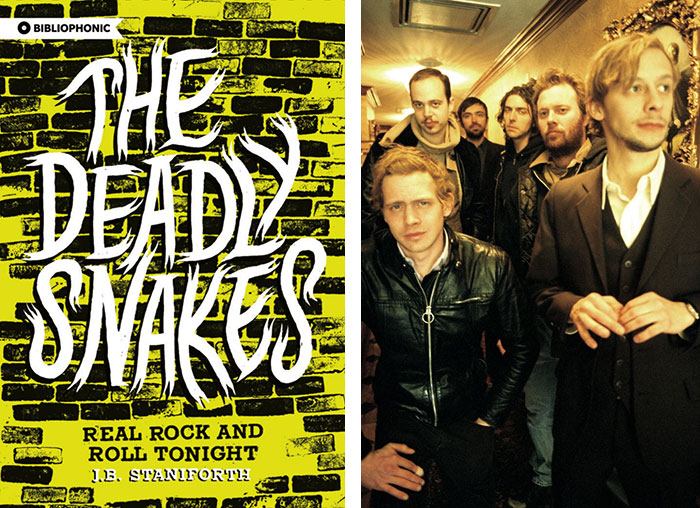

Band photo: Jannie McInnes/myspace.com/thedeadlysnakes

Band photo: Jannie McInnes/myspace.com/thedeadlysnakesIn the late summer of 2005, Toronto’s celebrated garage soul combo the Deadly Snakes gathered for ten days in a rural Ontario cabin to record their album Porcella. Though nobody said so at the time, each of the band’s six members knew that it would be the last time they made a record together. It was still more than a year before they’d play their final shows, but even in the cabin each young man knew already what he would eventually admit to his bandmates: touring and sharing a stage wasn’t fun anymore, and they feared losing the friendships that had been the band’s core since its inception a decade before.

There are hints of the Snakes’ coming end throughout Porcella, a rich and moody album larded with sadness and resignation. Yet each member of the group recalls the time spent in the cabin recording the record as a blissful interlude. Singer/organist Max McCabe-Lokos says of the Porcella session, “It was one of the best times of my life. I loved it.” The atmosphere of satiation and constant practice in the cabin, he maintains, worked magic on his musical ability. “The things my hands were doing, that I didn’t even know I could do, by the end of it, were amazing. I was doing stuff that I didn’t even understand how I was playing.” Piecing together an album whose lyrical themes dealt with emptiness, regret, and the dread of growing old, the band drank fine wines and spirits and dined every night on huge and sumptuous meals.

It’s the prosciutto, though, that first comes to mind when any ex-Snake talks about the recording of Porcella: McCabe-Lokos acquired an entire leg of cured pork as the session’s icon of excess. He hung it directly over the mixing board and left a knife nearby, allowing anyone passing to cut a piece for himself as he wished. Engineer Josh Bauman recalls he began each morning by wiping up the puddle of pork grease that had dripped onto the cover of the mixing board overnight.

The week’s rhythm drifted easily between playing, recording, and feasting. Because many of his parts wouldn’t be recorded until later on, saxophonist Jeremi Madsen used his downtime to make food runs into town and prepare enormous meals as the rest of the band put songs to tape.

“At the end of laying down a bunch of bed tracks, we’d walk into the kitchen and Jer’d have these incredible meals ready for us,” says drummer Andrew Moszynski. The band went so far as to list dinner highlights in the album’s liner notes, including baked trout stuffed with sorrel, wild mushrooms à la bordelaise, black pudding, crêpes with sabayon sauce, and beer can chicken.

That they should outgrow their juvenile disarray and develop adult tastes is not remarkable in itself. What is surprising about the career of the Deadly Snakes is that not only did they use the turmoil of growing up as the foundation for four critically acclaimed records, but they continued improving as they drew to the end of their arc, and incredibly broke down the band without ending the boyhood friendships that had struggled through a decade in pursuit of rock and roll. Despite the sustained conflict between passive lead singer/guitarist André Ethier and hot-blooded singer/organist/bandleader Max McCabe-Lokos, which had earlier exploded into an on-stage fistfight in New York, the band’s time together in the cabin sustained the bonds among its members, both musically and personally—at the same time as it enabled them to produce one of the decade’s finest albums.

To those who witnessed the band in their early years, the Deadly Snakes in their final era, a decade on, would have presented a startling contrast. For a downtown band that began bristling with adolescent antagonism, who dressed and acted like a retro street gang as a counterpoint to music that ran loose, wild and violent, they seemed unlikely to end their run as refined young men eating, laughing and playing reflective and mournful songs in a rural cabin. Even bound together as they were by a friendship dating back to high school, their internal history was peppered with conflict and violence (including one instance in which three Snakes threw the dictatorial McCabe-Lokos across a hotel room). No one—not even the band—could have predicted the career that would take the Deadly Snakes from the frantic, punk rock and roll of their first LP, Love Undone, to the dark, careful pop of their swan song, Porcella.

Yet above all, what set the Deadly Snakes apart from the vast majority of their peers—in garage rock, in Canadian popular music in general—was not their ability to grow and change, but their ability to do it well. Many bands make one exciting album before following “new directions” that lead them into wilting self-indulgence, but few start out great and young and wild, and get better as their records grow more challenging and complex. Fewer still have the good sense to recognize that, after having done their best work, the only dignified choice remaining is to disband at the height of their prowess, their friendships intact, maintaining the reputation of a band that never made a weak record.

The Deadly Snakes garnered little attention from the music industry or press in Canada. As Canadian “independent” music was exploding worldwide with the popularity of Montreal’s Arcade Fire and Wolf Parade, and Toronto’s Feist, Stars, and Broken Social Scene, the Deadly Snakes remained largely unknown outside of the garage rock underground they’d outgrown years before. The music industry only formally noticed them a month after they dissolved, when they were nominated for the 2006 Polaris Prize; they declined to reform to play at the ceremony.

McCabe-Lokos says, “My attitude was, ‘ No! I don’t want to bring my organ down there. We broke up!’”

* * *

Like all great rock and roll bands, the Deadly Snakes began in a basement.

Monday nights in high school, the four friends from west end Toronto who would comprise the band’s core from beginning to end—McCabe-Lokos, Ethier, Moszynski, and gifted trumpet player and multi-instrumentalist Matt “Matt-Dog” Carlson—held a weekly ritual they jokingly called “Boys’ Night Out.” (“Like we were a bunch of guys hanging out in the garage,” laughs McCabe-Lokos.)

Initially, they met in a doughnut shop for coffee and cigarettes, but soon migrated to Ethier’s parents’ basement, where they could furtively drink. Ethier, who had already begun playing and recording his own music, had instruments lying around, so it made sense that their camaraderie turned musical.

From one basement, the band—initially known as the Boys Night Out Band—struck out to another. They made their shaky debut as a four-piece downstairs from a laundromat in Kensington Market during a birthday party for McCabe-Lokos’s brother Nick. Having agreed to play the party as a dare to one another, they quickly cobbled together a handful of songs, learned a few covers of bands like the Troggs and steeled themselves to play live for the first time.

“When we played the birthday party,” McCabe-Lokos says, “We needed to make up a fake name for our fake band, and decided on the Deadly Snakes. The joke was that we had to be, like, a band, with a real band name. Then the band went on and we were stuck with it.”

They chose the name, Ethier recalls, to invoke the image of the sort of gang they might have been in high school in the ’50s. The band, he says, was “supposed to be a memory, like something that had already happened.

“We thought that name was really funny,” Ethier chuckles ruefully, “when it was only supposed to last a few months.”

Chris “Chico” Trowbridge, a former producer of CBC Television’s The Hour and current producer of CBC Radio 1’s Day 6 with Brent Bambury, was an early mentor to the band, releasing their first seven-inch single on his record label Crazy Money. He was at their debut show in the laundromat, where he met the band for the first time. As much as the show was intended to be a joke, for Trowbridge, the introduction was striking.

“So I follow the flyer directions down an alley,” he remembers, “down a set of stairs into the basement. There’s hardly anybody there, and this little kid, he looked like a twelve-year-old, comes up to me and aggressively goes, ‘ Can I help you? ’ I tell him I’m there for Nick’s birthday, and he says, ‘How do you know Nick? ’ I say, ‘I’m a friend from school. He invited me.’ That was Max, trying to kick me out of this party that had eight people in it. And he looked like a little boy, like a child. I thought, ‘What the fuck is this? ’”

When the band finally played, Trowbridge says, “They were borderline terrible—that was one of the great things about the Snakes at the beginning. They were brilliant too—they had written these great songs, these complicated soul ballads, that they could barely play.”

Especially striking to Trowbridge was a ballad the band never recorded called “The House of Love,” which captured, as much as Love Undone’s liner notes eventually would, the band’s founding principles. It was, he says, “this sad song about the ‘house of love,’ and when you go there, you must get married—which was a bad thing! I’m older than those guys, eight or ten years older, and listening to this I’m wondering, ‘What are these little kids doing, singing about getting married? ’ They were so naïve, but really sophisticated at the same time.”

Excerpted from The Deadly Snakes: Real Rock and Roll Tonight by J. B. Staniforth (Invisible Publishing, 2012).