I was late coming to Stieg Larsson and his wildly popular Millennium Trilogy. Last spring, when I started reading the first volume, some 20 million people had already beaten me to it. By August, when I finished the third, that figure had almost doubled. Numbers that big—phenomenal even beside such recent literary juggernauts as Harry Potter and The Da Vinci Code—almost always result from word of mouth. But the buzz over Larsson’s books began even before they were published.

It started shortly after he submitted the manuscripts of all three novels to his Swedish publisher, Norstedts, in April 2004. Word spread quickly, and when the Frankfurt Book Fair rolled around that October publishers from all over the world were clamouring for a look. Translations were commissioned shortly after the first book appeared in Stockholm in early 2005, under the title Men Who Hate Women, and from there the groundswell grew, country by country. By the time it reached North America in 2008, as The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, not even a bad review in the New York Times could stop it.

I’m a fan of crime and espionage fiction, but the Millennium books were different. There was something mysterious about how, despite their obvious flaws, they drew you relentlessly into a world that was both familiar and strange. Instead of seeing that world from the perspective of a police force, detective agency, or newsroom, you saw it through a small magazine with big ambitions. Like his main character, Mikael Blomkvist, Larsson had been a journalist and a magazine editor, and I wondered how much of his own life had gone into his books? Or was I simply fascinated with Larsson’s Sweden, a country I’d always dismissed as being pretty much like Canada, only with more blondes, fitter grandmothers, and a better sense of design? His books made me want to know more.

When I went to Sweden last September, it was for another purpose altogether. My brother-in-law, Gordon, had recently died of an inoperable brain tumour, and my wife, Patricia, and I had gone to attend his funeral in Kungsholmen kyrka, a stately seventeenth-century church surrounded by a green park in Kungsholmen, one of the largest of the islands and headlands that comprise the city of Stockholm.

Coincidentally, the church was only a few blocks from the office where Larsson had suffered a fatal heart attack shortly before the first book in the trilogy was published in Sweden. As we listened to the pastor deliver the eulogy in soft, melodious Swedish, Larsson was on my mind, because it was Gordon who had introduced me to the novels, which had in turn fired my curiosity about Gordon’s adopted country.

A Glaswegian by birth, Gordon had come to Sweden as a young man in pursuit of a love that didn’t pan out. He stayed on, found a greater and more lasting love, settled down, learned the language, and made a life for himself that included both print and television journalism. Recently, he’d been travelling to China to teach the Chinese how to do stand-up news reporting. He was at the top of his game when the cancer struck, but he never lost his droll sense of humour: as his battle with the disease intensified, he began referring to himself as “the Scottish Patient.”

We were both fans of Henning Mankell, another internationally renowned Swedish crime writer. Gordon and his wife, Charlotte, owned a summer place in Skåne, the southernmost county in Sweden, not far from the picturesque coastal town of Ystad, where Mankell’s fictional detective, Kurt Wallander, works for the local police detachment. Skåne is a sunny part of Sweden, a place of rolling farmland and woodlots not unlike parts of southern Ontario, but Mankell’s tales are anything but sunlit; the lives Wallander encounters in his dogged pursuit of justice are filled with menace, sinister obsessions, and extreme cruelty. It’s common knowledge among aficionados of Nordic crime fiction that all is not as it seems in the sunny lands of Scandinavian socialism.

“Now that you are into Swedish crime fiction,” Gordon emailed one day, “you must try the Stieg Larsson books!”

And so it began. I bought a softcover edition of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and started reading.

Like many who come to Larsson cold, I found the book hard to warm up to. It runs to well over 800 pages, and although it’s touted as a thriller it begins at a maddeningly leisurely pace, almost like a Victorian novel. There is a mysterious prologue that includes a lengthy botanical description of a dried flower. Next, a respected investigative journalist, Mikael Blomkvist, loses a defamation suit brought against him by a wealthy financier and is fined 150,000 kronor—approximately $20,000, a slap on the wrist by Canadian standards. In addition, he’s sentenced to three months in prison, no doubt some Swedish Club Fed with uniforms by H&M and furnishings by IKEA. Then comes a rambling, twenty-five-page flashback involving a sailboat trip to a place called the Archipelago, where Blomkvist and a former schoolmate get plastered on aquavit as Blomkvist hears the convoluted tale that will get him sued. Next, there’s a lengthy introduction to Milton Security and its CEO, Dragan Armansky, complete with his exotic family tree and a detailed history of his business. By this time, it is page 47, and still no sign of a plot. I put the book down and turned to other things.

The following Sunday, Gordon phoned from Stockholm and asked how I’d liked it.

“I bogged down,” I said.

“Give it another try,” he said. “Just make sure you have a free day ahead of you.”

So I started again, from the top. This time, it was different. Maybe I’d had a good night’s sleep, or maybe I had accepted the fact that this wasn’t going to be the kind of thriller that begins with a bloated corpse floating in on the tide with its fingers cut off. I began to realize that with Stieg Larsson God is in the details.

In addition to being a reporter, Blomkvist is also part owner and publisher of an ambitious little magazine called Millennium that had published his defamatory story and presumably bears some of the blame. It has a circulation of about 20,000 (pretty decent in a country of nine million), but appears to have little capital, and it’s losing advertisers because of the lawsuit. Blomkvist, however, is convinced that he was fed false information to destroy the magazine, and when the editors gather to discuss what to do next, their main concern is how to survive so that one day they can bring down their wealthy adversary for good.

I’ve been involved in several small Canadian magazines and know what frail vessels they are; how exhilarating the struggle to launch and keep them afloat can be; how pathetically dependent they usually become, either on government largesse or the backing of fickle investors; not to mention how hard it is to get investigative pieces off the ground on a tiny budget. This Millennium crowd lived in a world I knew, but it felt almost like a parallel universe. Larsson now had my full attention.

It’s only after page 47 that we meet one of the major reasons for the trilogy’s success: a troubled young woman of uncertain sexuality who dresses like a punk, has hair “as short as a fuse,” and sports the eponymous dragon tat on her left shoulder, along with a large but undefined grudge. Like Garbo, Lisbeth Salander wants to be left alone. Larsson has endowed her with powers that verge on the miraculous: he’s made her a genius hacker who can perform what she calls “hostile takeovers” of other people’s computers; he’s also given her a photographic memory, and a knack for research that any reporter would die for. These skills have earned Salander a secure position as Armansky’s star researcher, and we first see her in action as she presents him with a confidential report on Blomkvist, commissioned, for reasons not yet clear, by a wealthy client.

By Canadian standards, the material she turns up on Blomkvist could only have been gathered by a serious invasion of his privacy, but this is Sweden, where invasion of privacy is apparently routine. The report ultimately brings Salander and Blomkvist together, and thus, in a single stroke of brilliant plotting, Larsson launches an unlikely partnership that, over the course of the three novels, will ripen into one of the strangest, most haunting relationships in modern popular fiction.

When I finally put the book down a day and a half later, I was both elated and perplexed. It wasn’t just that the odd couple had managed to get to the bottom of a breathtakingly awful series of crimes; they had also managed, by publishing Blomkvist’s exposé in Millennium, to defeat their corporate nemesis, who, in one of the book’s more memorable lines, “was devoting himself to fraud that was so extensive it was no longer merely criminal—it was business.” In Canada, the way they did it—Salander illegally hacking into the man’s computer, Blomkvist claiming the material came from an anonymous source—would probably have landed them in court, in the unlikely event that they had succeeded in getting the story past the legal department.

That Sunday, I asked Gordon if journalists could really get away with that kind of thing in Sweden.

“It’s our dirty little secret,” he said.

For a second opinion, I contacted Anders R. Olsson, a freelance journalist in Stockholm who specializes in free speech and media law issues, and is the author, most recently, of a book called Wanted: A Technical Solution to the Problem of Evil, about the threats to free speech posed by Internet filtering.

I asked him if it was believable that Blomkvist could protect a source (Salander) who provided illegally gained information in such a high-profile case.

“Well, yes,” he said. “Swedes do have reasonably strong protection for sources; that’s true. There is a constitutional right for every citizen to speak to the media, and you cannot be punished in any way because you’ve done that. If you also wish to do that anonymously, you can demand anonymity from the journalist. And if that’s the agreement, the journalist can actually be put in jail if he reveals the source.”

I felt as though I’d stepped through the looking glass. I’d read somewhere that Sweden first passed these press laws back in 1766. “How did that happen? ” I asked.

“It’s something of a mystery,” Olsson replied. “I mean, in 1760 Sweden was a poor, rather backward country of peasants in the northern part of Europe, and not in any way radical. So it’s rather strange that we were actually the first country in the world to have constitutional protection for free speech.”

Sweden’s press laws also guarantee Swedish citizens access to public documents but, as Olsson pointed out, this right is being eroded by the new media. “I don’t have a right to get a copy of electronically stored information in an electronic format, which means that if it’s a lot of information I cannot really deal with it,” Olsson said. “I can’t have 40,000 pages of written materials handed over to me, because it would cost me fifty cents a page. [So] it’s a lot harder to get the critical information you want if it’s in the electronic format than if it’s on paper. We were definitely the most open country in the world up until the ’80s or so. I don’t think we are anymore.”

The shifting sands of Sweden’s press laws may be at the root of the high-profile pickle that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has found himself in. According to an article in the Columbia Journalism Review last September, Assange apparently assumed that if his servers were located in Sweden, WikiLeaks would enjoy the same constitutional right to protect its sources as the rest of the Swedish media. But the rules for new media are different. To qualify for protection as a website, WikiLeaks would have to register as a Swedish entity and designate a “responsible editor” who, among other things, would have to be a legal resident of Sweden. Assange has applied to become a Swedish resident, but now that he is facing sexual assault charges there, the likelihood of him succeeding appears to be fading fast.

I went straight for the hardcover edition of The Girl Who Played with Fire—which Larsson had originally wanted to call The Girl Who Fantasized About a Gasoline Can and a Match. If Dragon Tattoo is a classic whodunit, Played with Fire deliberately shifts gears. He sets his protagonists in the centre of a fast-paced police procedural, paralleled by amateur PI work from Blomkvist, who manages, as convention dictates, to stay one step ahead of the cops. Salander has gone to ground and is hiding in plain sight in Stockholm when, amid screaming tabloid headlines, she becomes the prime suspect in a triple murder. Two of the victims were collaborating on a story about sex trafficking for Millennium, and this plunges Blomkvist into the middle of a frantic effort to save the story while trying to prove Salander’s innocence.

It’s all immensely entertaining, but astonishing at the same time. How in the world was Blomkvist able to dance with the detectives while withholding vital information from them, not only hiding sources but telling them he was doing so? Canadian police would have had his ass in a witness box or a jail cell before he could say skol.

I sent a query to the Swedish Association of Crime Reporters and received a reply from Petter Sundsten, a former newspaper crime reporter who produces Efterlyst (Wanted), one of Sweden’s longest-running true crime television shows. He wrote that “even though Blomkvist is some form of a ‘dream reporter’ (and some kind of alter ego for Stieg Larsson),” the books give a fairly realistic picture of how crime reporters work in Sweden. “The big exception,” he said, “is when it comes to crimes regarding the security of the state, treason, espionage, or unauthorized dealing with classified material.” In such cases, “the journalist can only be asked for the name of the source in an actual trial, if it gets that far, which is very uncommon. He/she will then only be asked if the person on trial is the one who provided the secret documents/information: yes or no? The court cannot, in the case of no, ask any further questions. And of course, most journalists would not answer at all.”

How typical is it for reporters like Blomkvist to conduct their own parallel investigations of a crime without getting a lot of flak from the police? “Very common,” Sundsten replied, “especially tabloid reporters.” But the same constitutional protections and obligations apply, he said. Sources, even those inside the police force, must be protected. Likewise, when a case has gone through the courts all the related police records are supposed to be accessible, since they are, by definition, public documents.

That helps to explain how Larsson was able to amass a huge trove of material, not only for his own investigations into extreme right wingers, but also for his research for the Millennium books, which, as he told his editor, are heavily based on actual cases.

In June, Patricia and I made a brief visit to see Gordon and Charlotte at their summer place in Skåne. Gordon was still able to talk, but the tumour was rapidly disabling his nervous system, and he was going blind and deaf; it was heartbreaking. When we went to bed the first night, there was a copy of the third book in the Millennium Trilogy, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, on our bedside table. Along with it was a brochure offering a tour of places in Ystad frequented by Henning Mankell’s fictional detective, Kurt Wallander. In Swedish crime fiction, it seems, the line between fiction and reality is blurry indeed.

Two days after we said goodbye to Gordon for the last time, he was airlifted to a palliative care hospice in Stockholm. There were no more emails or telephone calls. I started reading volume three.

Once again, Larsson had shifted genres. The book, called The Castle in the Air that Exploded in Swedish, is more like a John le Carré novel crossed with a Scott Turow courtroom drama. This time, the villains are not bikers, drug dealers, or serial assassins, but pillars of society fully prepared to break the law, undermine the constitution, and even murder in the name of national security and, of course, to save their own skins. For reasons I can’t get into without spoiling the plot, that means putting Salander away for good. This time, the story Blomkvist is working on for Millennium is Salander’s story: writing it is the best way he can think of to save her. But that makes him a target for the bad guys, too.

Possibly because Larsson didn’t live long enough to complete the editing process, Hornet’s Nest is the most ragged of the three books. There’s a jarring moment near the end, when Blomkvist says to his sister, who has been acting as Salander’s lawyer, “When it comes down to it, this story is not primarily about spies and secret government agencies, it’s about violence against women and the men who enable it.” Stieg Larsson, the novelist who had beguiled us for more than 2,000 pages, suddenly vanishes in a puff of smoke to reveal Stieg Larsson, the crusading journalist obsessed with driving home a point. It was as if Herman Melville had decided to end Moby Dick by having Ishmael pop up in his coffin and say, “When it comes down to it, this story is not primarily about an insane whaling captain bent on revenge; it’s about the systematic slaughter of one of our most magnificent marine animals and the men who enable it.”

It was time for me to find out more about Larsson and who he was before he became so famous. And it wasn’t hard to do. With the release of the third volume, and with worldwide sales approaching 40 million, the press and the Internet teemed with stories about Larsson the man, Larsson the journalist, Larsson the feminist, Larsson the pinko, Larsson the social militant. There were fan sites where avid readers discussed everything from what ring tone Blomkvist might have on his cellphone to whether the trilogy could be read out of order.

There were also two new books about Larsson in English: one by British crime fiction maven Barry Forshaw, called The Man Who Left Too Soon; and another by a colleague of Larsson’s, Kurdo Baksi, titled Stieg Larsson, My Friend. Both were rushed into print to capitalize on Larsson’s surging popularity, and the haste sometimes shows. Baksi’s memoir is perhaps the more revealing; it’s heartfelt, with a strong undercurrent of personal obligation to Larsson and the causes they shared. And Larsson’s partner of thirty-two years, Eva Gabrielsson, was getting ready to release a book of her own, with the working title The Year After Stieg. It will tell the story of how she dealt with her grief at his untimely death, and her treatment at the hands of the Swedish state, which, because Larsson died without leaving a will, awarded his entire estate—now worth many tens of millions of dollars—to his father and brother. They in turn have refused to deal with Gabrielsson until she hands over a computer thought to contain several hundred pages of a fourth novel.

Not surprisingly, there are several competing narratives in circulation concerning what Larsson was like, much of it silly stuff about how many coffees or cigarettes he consumed a day, or whether he wrote the books himself. Baksi describes him as a man who shunned the limelight, and who possessed a powerful sense of empathy with the victims of racial or sexual violence. Larsson’s opposition to hate crimes was visceral, not intellectual. But I also noted a tendency to inflate his prior reputation as a journalist. A close friend of Larsson’s, Graeme Atkinson, writing his obituary in the British anti-fascist magazine Searchlight (the inspiration for Expo, the magazine Larsson co-founded in 1995), made the exaggerated claim that Larsson had “covered every major world news story—as it broke and unfolded—for almost two decades.” The truth is that from 1979 to 1999, Larsson held down a desk job at Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå (TT), a Stockholm press agency, where he was essentially a copy editor, and designed pages, wrote captions, provided graphic artwork, and contributed occasional features that usually involved his two serious interests: crime fiction and right-wing extremism. The job allowed him to pursue his real vocation, as a magazine editor and author.

While Baksi’s admiration for Larsson’s political activism and personal courage knows few bounds—at one point, he describes Larsson as “a mixture of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, the Dalai Lama, and Pippi Longstocking”—he thinks less of Larsson as a conventional journalist. They often disagreed about journalistic ethics, and Baksi even accuses Larsson of “professional misconduct” at TT, for writing about neo-Nazi death threats levelled against himself and some colleagues at Expo. The threats were real enough; the sin was in writing about them in the third person.

Among his peers, Larsson’s pre-Millennium reputation was nothing out of the ordinary, though Expo was—and still is—respected among journalists as a reliable source on right-wing extremism. Larsson had co-authored two books about right-wing movements, and was sometimes called in as a consultant by organizations like Scotland Yard. Thanks to his experience with death threats, he wrote a handbook for journalists, called Surviving the Deadline, on how to confront the dangers of their trade. The Swedish Union of Journalists plans to reissue the book with an English translation, as soon as the rights can be sorted out.

One of the few pieces of Larsson’s non-fiction writing I could find in English was a paper he gave at a conference in Paris sponsored by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe in June 2004. His contribution, on the Internet and hate crimes, stands out among the jargon-laden papers presented at the event. It contains many of his core beliefs, for example that politically motivated violence is always preceded by “a period of slander, innuendo, or rumour mongering that is meant to legitimize the actions that follow”; and that the underlying aim of hate propaganda is “fostering suspicion against democratic society, democratic institutions and democracy itself.” It is lucid, well argued, and, in its own way, a small blow to the claim put forward by a former colleague at TT, that Larsson couldn’t have written the Millennium Trilogy because he didn’t have the chops.

But the biggest question surrounding the trilogy, apart from what makes it so popular, is what drove him to write it in the first place? Larsson apparently told people the books would be his retirement fund, a plausible enough explanation for someone who never had much money. Baksi says Larsson had always been fascinated by popular genres, especially crime and sci-fi. He published two sci-fi fanzines in the ’70s, and was an avid reader of mainstream crime and espionage fiction. He wrote a few crime stories of his own in the ’90s but threw them away. Eva Gabrielsson told Swedish TV that the Millennium books “began with [his] frustration that there wasn’t a forum to tell people what today’s society is really like. About injustice. How cruel discrimination against women and violence against women really are. All the things he couldn’t express at Expo or in other contexts.”

It’s almost too pat an answer, and yet it seems convincing. Expo focuses almost entirely on the extreme right, whose members, though undoubtedly dangerous, are probably the most predictable opponents imaginable. Larsson took them seriously, but for a man of his intelligence this must have required saintlike dedication. It’s easy to imagine him wanting to broaden his horizons, so he invented an imaginary magazine, Millennium, with a mandate to take on the world.

Gabrielsson, who often co-wrote articles with him, recognized that something new was happening when he started to write the Millennium books. “This time around,” she told Swedish television, “I said, hang on, this is different. This comes from a wellspring. The smallest pebble I drop in might do some harm.”

We may never know what that wellspring was, but we can guess. Like much great literature, and Nordic literature especially, the Millennium Trilogy is a saga of revenge, a massive settling of accounts. And not just against men who hate women; the books are a huge “fuck you” from a smart, working-class kid to a journalistic and political establishment he never really belonged to, despite having tried once, and failed, to get into journalism school.

Was Larsson a vengeful person in real life? Baksi says that his one weakness was his inability to forgive anyone who had ever crossed him or let him down. “Up north, where I come from,” he quotes Larsson as saying, “you never forgive anyone for anything.”

But if Larsson never forgave others, perhaps he never forgave himself either. Baksi’s book reveals—and Eva Gabrielsson confirms—that when Larsson was fourteen he watched helplessly while three of his mates gang-raped a young girl. Later, he tried to apologize to the victim, but she angrily rebuffed him. “That was one of the worst memories Stieg told me about,” Baksi writes. “Presumably, it was not his intention to be forgiven after writing the books, but when you read them it is possible to detect the driving force behind them.”

There’s a telling moment in Dragon Tattoo, when the industrial patriarch, Henrik Vanger, tells Blomkvist about the impact the loss of his grand-niece, Harriet, had on him:

“For the last thirty-six years,” Vanger says, “not a day has gone by that I have not pondered Harriet’s disappearance. You may think I’m obsessed…”

“It was a horrific event,” Blomkvist says.

“More than that. It ruined my life…I can’t forget what happened…But the funny thing is, the older I get, the more of an all-absorbing hobby it has become.”

“Hobby? ”

“Yes…when the police investigation petered out I kept going. I’ve tried to proceed systematically and scientifically. I’ve gathered all the information that could possibly be found—the photographs, the police reports. I’ve written down everything people told me about what they were doing that day. So in effect, I’ve spent almost half my life collecting information about a single day.”

It’s hard to believe that Larsson, a masterful hunter and gatherer of information about dark human passions, was not talking about himself.

The day after Gordon’s funeral, Patricia and I joined a group of around fifty people at the foot of Bellmansgatan in Södermalm, close to Mikael Blomkvist’s fictional bachelor pad, which Larsson situated in a very real eighteenth-century building with a spectacular view over Stockholm, a city without skyscrapers. The Millennium Tour, run by the Stockholm City Museum, has become a pilgrimage for legions of Larsson fans from around the world. Following in the footsteps of his two protagonists, we walk up and down the steep cobblestoned streets and along the broad thoroughfares of the island. Södermalm is a gentrified but still somewhat down-at-the-heels part of the city, filled with beautiful old architecture, quiet parks, and ugly Soviet-style apartment blocks. We pause at the restaurant where Blomkvist is almost gunned down, and at the coffee shop where Salander walks out of his life, as she thinks, forever. Our guide, a bright, young multilingual teacher, occasionally fires questions at us, as if to test our knowledge of the text, and interlaces her commentary with excursions into Swedish history that are as full of blood and gore as Larsson’s novels.

Oddly enough, nothing in the books had prepared me for the experience of walking those streets. Larsson is always precise, sometimes obsessively so, about where his characters walk, which Tunnelbana stop they get off at, and where they drink, but his writing seldom evokes place or atmosphere. His world is largely one of information and action; the rest you have to fill in for yourself.

Many commentators have pointed out a kind of moral geography in Larsson’s Stockholm, with the good guys living mostly in Södermalm and the bad guys across the water, in Östermalm and Kungsholmen and beyond. But the geography also provides clues to his deeper intentions. For instance, the building where Salander buys herself a luxury hideout is not far from the fictional Millennium offices, which in turn are a short block away from the 7-Eleven where she buys her Billys pan pizzas and her Marlboro Lights. Far from putting Blomkvist out of her life, she appears to have arranged things so that an accidental encounter with him is always possible. Knowing this adds a new dimension to their unlikely love story.

Most of all, though, the Millennium Tour’s popularity confirms that a wonderful literary alchemy has taken place. In five years, Larsson’s protagonists have become as real to his readers as that other unlikely crime-busting duo, Holmes and Watson.

An hour after the tour ends, I’m standing in a skylit room on the seventh floor of the solid seven-storey apartment building in Kungsholmen where Larsson suffered his fatal heart attack. It looks pretty much like any other editorial office I’ve ever been in: spare, functional, without many creature comforts or personal flourishes, as though individuality were swallowed up in the intensely collective effort of putting out a magazine. I’m here to talk with Daniel Poohl, Larsson’s second successor as editor-in-chief of Expo, about the magazine that was an important part of Larsson’s real life, and his other magazine, the one he invented in his mind.

Tomorrow is election day in Sweden, and Expo will be buzzing with staff and volunteers. An ultra-nationalist anti-immigration party, the Sweden Democrats, is poised for the first time to win seats in the Riksdag, Sweden’s parliament. Larsson and Expo have been tracking the party’s evolution for years, going back to its beginnings during the virulent racist movements of the ’80s. For now, the office is quiet, the only sound the steady drumbeat of heavy rain on the skylights.

Poohl, a slender man of twenty-nine with dark-rimmed designer glasses and a fashionable shadow of a beard, takes me on a quick tour. There’s not much to see: a kitchen counter, some ten workstations, a square conference table surrounded by chairs, a large whiteboard with indecipherable bits of handwritten information. Just behind me, there’s a cubbyhole not much bigger than a walk-in closet, with bookshelves and a sofa-like bed covered with blankets and throw cushions.

I imagine Larsson (a notorious insomniac and night owl) relaxing here, dreaming his dreams—plotting out his future novels, perhaps.

Poohl gives me a brief history of Expo: founded in 1995 by Larsson and others to confront the rising incidence of organized right-wing violence in Sweden, which culminated that year when seven people were murdered by neo-Nazis; established as a foundation with a mandate to “safeguard democracy and freedom of expression against racist, right-wing extremist, anti-Semitic, and totalitarian tendencies in society.” The magazine’s core was the extensive archive of materials about the extreme right that Larsson had already spent more than half his life compiling.

Expo’s premiere issue attracted a few subscribers and much attention, not all of it welcome. Some neo-Nazi groups began a campaign to shut down the magazine. Staff members received death threats, and the windows of retailers that sold Expo were smashed, its printing company vandalized. Two of Sweden’s largest evening tabloids, Aftonbladet and Expressen, stepped in and, in the name of solidarity, printed and distributed 800,000 copies of Expo’s next issue as a supplement. But Larsson remained a marked man, haunted by hate mail and plots against his life. This was the reason he’d never married Eva; as a couple, they’d be easier to find.

In 1998, the volunteer staff suffered mass burnout, but Larsson and a handful of others soldiered on. From the late ’90s until 2003, Expo was co-published with Svartviitt (Black/White), a magazine about racial integration run by Kurdo Baksi. By 2004, the year Larsson died, Expo was back on its feet as the Expo Foundation, with a publishing arm (the magazine and its website); an educational arm that provides speakers and resources to schools, politicians, police forces, and other groups; and a research arm that issues an annual report on right-wing extremism in Sweden. Today the magazine is a colourful, handsomely produced quarterly with a circulation of just over 2,000, a modest newsstand presence, and a small staff of paid reporters and editors filled out by volunteers. It has private backers and grants from organizations like Artists Against Nazis. The magazine recently received a prize of 200,000 kronor (around $30,000, established by Larsson’s father and brother and named in his honour, but so far that’s all the benefit it has received from the Millennium Trilogy’s huge success. Expo has won other awards, but the one Poohl is proudest of remains the Torgny Segerstedt Freedom Pen Award, named after a Swedish scholar and newspaper publisher who openly stood up to Hitler despite Sweden’s official neutrality.

Is there much of Expo in Millennium? I ask. Poohl laughs. “When I read the book,” he says, “I couldn’t see anything from Millennium in Expo, to be honest—quite the opposite. I saw Millennium as a kind of fantasy magazine.” There’s a moment in the first novel when Millennium suddenly gains 3,000 new subscribers in response to one of its stories. “When I read that, I started to laugh, because it was quite clear that Stieg had no idea what would actually happen if 3,000 people suddenly subscribed. I mean, your computer would explode.” And Poohl wonders, almost wistfully: had Larsson survived, would he have used all that money to start a magazine like Millennium, with a broader mandate than Expo’s? The question hangs in the air, unanswered.

Did Poohl think, as many do, that there are two Stieg Larssons—the magazine editor, researcher, and activist on one hand, and the thriller writer on the other? “No, I think it’s the same person,” he says, “and I think the Millennium series wouldn’t have been possible were it not [written by] the real Stieg, so to speak. Because it’s so much about the topics he found interesting. If you knew Stieg, you would recognize them immediately.” Poohl says Larsson’s colleagues regarded him as an accomplished researcher, but his greatest contribution to the causes he fought for was “first of all his way of analysing and [writing] about quite complicated, complex political worlds in a very—is that a word?—accessible way that made it easy to understand. And that is quite hard to do. There are many books about far-right parties, and there are many academics trying to understand how they work, but for the people who don’t actually have the time, or don’t understand these academic pieces, I think Stieg played an important role.”

The fundamental idea underpinning the Expo project was, as Poohl puts it, that racism and democracy are incompatible. “Stieg always [said] that every person, every organization, every company, every trade unionist, has the possibility to act as a democrat, against racism and intolerance. We must have different voices and different actors in the anti-racist struggle. And that may be the most important thing Stieg taught me and many other people who work for Expo today.”

On the day Larsson died, he arrived at work to find the elevator out of service, so he trudged up the winding staircase to the seventh floor. He was overweight and out of shape, his body abused by years of too many cigarettes and cups of coffee, too much junk food, too little sleep. When he reached the top, he looked so awful that one of the staff decided to call an ambulance; Larsson collapsed before they could pick up the phone. Again, the broken elevator became a factor: the medics had to climb the same stairs and then carry him on a stretcher all the way back down. In an ambulance, one of the medics asked a colleague how old Larsson was. He tore off his oxygen mask and uttered his last words: “I’m fifty, damn it!”

Poohl was en route to work when he got a call saying Larsson had been taken to hospital. A couple of hours later, someone rang from the hospital with the news that he was dead. The Expo staff was devastated, of course, but decided that the best way to honour him was to carry on.

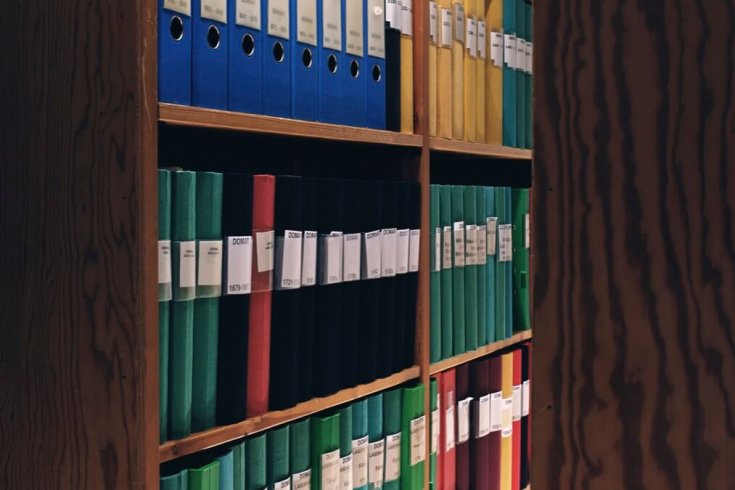

Before I leave, Poohl takes me down a hallway to show me the heart of Expo, and Larsson’s real legacy—the archive—in a compact room behind a locked steel security door. We enter through a tight passage between a set of huge shelves on wheels and runners. Poohl begins shoving them aside, one by one, showing me the contents. There are hundreds of metres of file boxes and ring binders, neatly catalogued and organized and easy to access. There are countless police records chronicling the trials and convictions in every traceable hate crime in Sweden. There are collections of right-wing publications, brochures, posters, internal memos, correspondence. There are files on businesses that sell Nazi regalia and white power music. There are books: Larsson’s own studies of the extreme right, and of the Sweden Democrats; Alan Bullock’s massive biography of Hitler; William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Do they have a copy of Mein Kampf? “Yeah, we should,” Poohl says.

I take one last look around at this monument to Larsson’s magnificent obsession, and then we slip out and Poohl locks the door.

“Okay, so that’s Expo,” he says.

“And Expo comes from ‘exposure, exposé’? ”

“Yeah, I think it’s a great name.”

We left Sweden the next day. On a layover in Amsterdam, in a tiny hotel room near the main station, I watched the Swedish election results on an English-language cable channel that looked and felt like BBC World, except that the announcers and reporters were all Chinese. The Sweden Democrats were the big news. They had captured only 5.7 percent of the vote, but thanks to the country’s electoral system they would win twenty seats in the Riksdag. The announcer predicted a fall in the value of the krona against the euro.

There was something almost surreal about this channel, so I kept watching. Then I realized it was broadcasting directly from the capital of China, where the kind of free speech that made Larsson’s life work possible is not even on the agenda. What I was seeing was some kind of simulacrum of a cable newscast, for export only. The announcers had the moves, the gestures, the tone, the phrasing down pat. But it still felt hollow, like a shadow play. I drank a silent toast to Gordon, praying none of this was his work.

It’s a brave new world out there. Larsson’s books have been translated into thirty-four languages, including Chinese. I raised my glass to the screen. “First he took Stockholm,” I said, paraphrasing our national bard. “May he take Beijing.”

This appeared in the March 2011 issue.