In 2020, schools in Canada faced the unforeseen obstacle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and they shuttered in-person learning. No matter where they were living, students had their lives disrupted. Later in the year, online learning was blended with new forms of in-person learning.

As case numbers began to rise again in Ontario in September 2021, I started grade nine and entered a social experiment known as the “quadmester.” Each day, I was forced to sit for two and a half hours in class for one subject, then repeat the process for a second subject. Those two courses lasted only eight weeks, but they used a curriculum designed to be taught over five months.

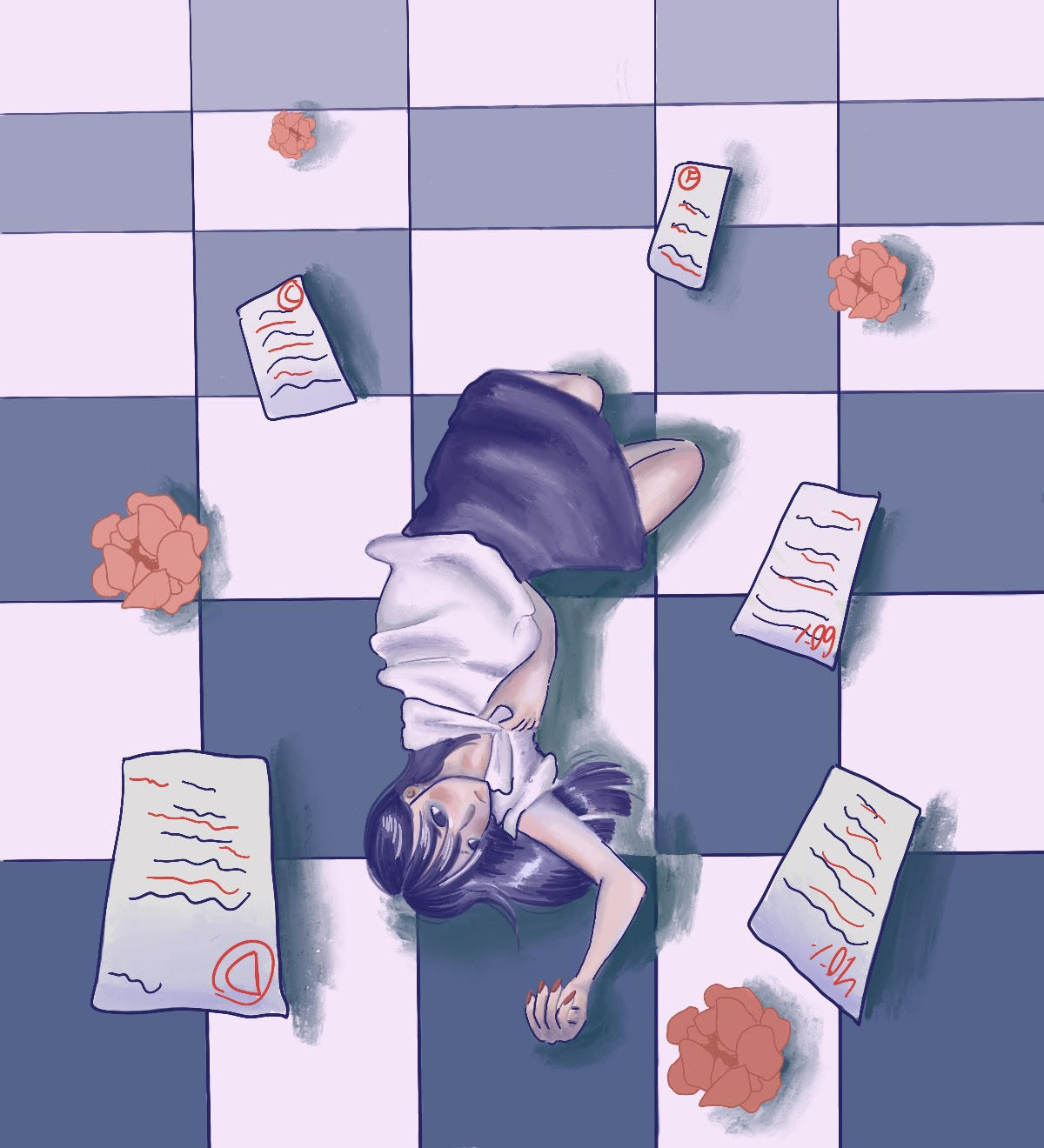

In my second week of high school, I caught a cold and, of course, was concerned that I had COVID. I stayed home, as instructed, and had to get a COVID test before going back to school. Thankfully, the test was negative, but the work I missed from being away for one day was the equivalent of three days of normal school. So, in the second week of high school, I had already fallen behind. It continued to go downhill from there. Mathematics, a subject I love, used to be fun. But, at the speed it was being taught, I had no time to absorb the algebraic formulas, practise them, and apply them; once the formulas were taught, the next test was always just a day away. Day after day, I had a sense of panic, worry about failure, and general stress from the high-intensity classroom, even though fear wasn’t something I had ever associated with school before. Classes have since returned to normal, but I still have questions about what happened, and I’m sure other students share many of them. What did the past two years of education do to us? And are we going to be feeling the effects of this for years to come?

Some school boards first experimented with the octomester model: students focused on one subject a day for twenty-two days, then switched to another subject, for eight subjects in total for the school year.

To remedy some of the deficiencies in the condensed style of the octomester, many school boards in Ontario, as well as at least one high school in Winnipeg, adopted the quadmester, as did some Saskatchewan schools, though they typically called it a quarter system. Some high schools in Saskatchewan also used a quint system of five separate blocks per year. Cohorts in all these models were designed to keep students within the same peer groups, with limited socialization to prevent the spread of COVID-19. For our two-month quadmesters, I was in a cohort of fifteen students for all my classes, though numbers varied. I even spent lunch break with the same students.

Lizzie Cameron, who just graduated from grade twelve at Paris District High School, in Paris, Ontario, says her school experimented with quadmesters. In fall 2020, she had to go “through a week’s worth of material in one day. So you tend to have major projects and tests much more regularly.” In math class, she says, “we did two units at a time, one in the morning and another in the afternoon. So we would have a quiz or a test or some form of evaluation every other day, as well as the regular worksheets. If you didn’t understand something right away, you were in trouble.” It felt like a stamina test, she says, and it took a toll on students’ mental and physical well-being.

Ryan Imgrund, a biostatistician and independent educational consultant who has worked with the government of Ontario, says that “the overall purpose of that system was to ensure that classes could move easily between in person and online.” He says the quadmester was a way to find a compromise between the octomester and semester system, which is why so many school boards adopted it.

Even though the quadmester is less intensive than the octomester, many students struggled with the pace of testing. Aidan Connolly, a student entering grade twelve at St. John’s College, in Brantford, Ontario, was taking two science subjects at once. Though he says his teachers were good, it was still overwhelming. He ended up taking two tests every week for the entire quadmester.

And then there’s the issue of focus. Holding a student’s attention at the best of times is a difficult task for teachers. A popular notion suggests that a student’s attention wanes fifteen minutes into a lecture; if so, in a 150-minute quadmester class, a student will lose their mental focus at least ten times.

The frustration about the inadequacy of quadmesters and online learning frequently brought about burnout and anger in students. Lucas Balog was a grade twelve student-council leader at Paris District High School when he returned to quadmesters and in-person learning in February 2021 and says he observed more divisiveness, fights, and aggression than in his previous years of high school. Lockdowns and online learning had tipped the scales toward a lot more students hating school, he says. “They should enjoy learning. They should enjoy seeing their friends.”

Some administrators say the quadmester system was the best option. Reg Lavergne, the superintendent of the Ottawa-Carleton Secondary School Board, says the quadmester system had some benefits. He says it was intended to keep students safe in classrooms. “It was a necessary step that everyone had to take. At the end of the day, I have 100 percent faith and belief in the teachers and their ability to care for kids and their ability to say, ‘Okay, given this situation, how do I change this? How do I modify this? How do I adjust it to help them?’” Lavergne says, “I think we also started to understand that learning can look very different and that’s okay.”

The future ramifications of the quadmester system are clear to educational consultant Monika Ferenczy. Because it compresses lessons into shorter amounts of time, quadmesters left teachers with “no time for review or remediation if students had a hard time with a particular concept.” She suggests that students will not remember what was covered when they take the next level class in the same subject. These learning gaps will need to be filled through other supports, such as tutoring.

Ferenczy notes that there is already a body of research demonstrating the pandemic’s impact on anxiety and depression. This means schools will need additional resources to support students in the years to come. A meta-analysis published by JAMA Pediatrics states that youth mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic have likely doubled.

As vaccination rates rose among high school students, many school boards returned to a normal schedule and dropped cohorting. By spring 2022, school boards in Canada had made the choice to return to invite students back to in-person learning and the tried-and-true semester model.

Students such as myself are thankful the social experiment of the quadmester has ended, resulting in the return of my well-being. Certainly, the educational systems we know today have never experienced a pandemic of this scale before, and the response was based on practicalities. Schools needed to open. Students needed to return to in-person learning. Teachers and students needed to be safe.

But, to me, it seems that this generation’s mental health and ability to learn were afterthoughts. Parents needed the schools open so they could go to work. Governments were pressured to get things back to normal. But at what cost? Will we look back on this period of the pandemic and realize that so much was lost?

I suppose only time will tell. As we continue to remain in the midst of the ever-present threat of COVID-19, we may be labelled “generation COVID” and be forgiven for our underlying anxiety, our apprehension toward the future, and, maybe, our lack of education fundamentals, which we lost along with our childhood. On the other hand, maybe we’ll have a future that just goes back to normal. I hope for the latter.