Listen to an audio version of this story

“With every tap, a new legend is born,” says a familiar voice as the bass booms and the Fountains of Bellagio in Las Vegas freeze over. A suited-up, turtlenecked Wayne Gretzky emerges. “A chance to grab destiny, defy the odds—and strike,” he says. The fountains freeze into the forms of enormous football players and dunking basketball players. It’s so Vegas. It could pass as a trailer for a reboot of The Terminator, but it’s actually part of a new TV blitz by sports-betting monolith BetMGM. The takeaway of the ad is clear: sports are fun—but winning money? That’s legendary.

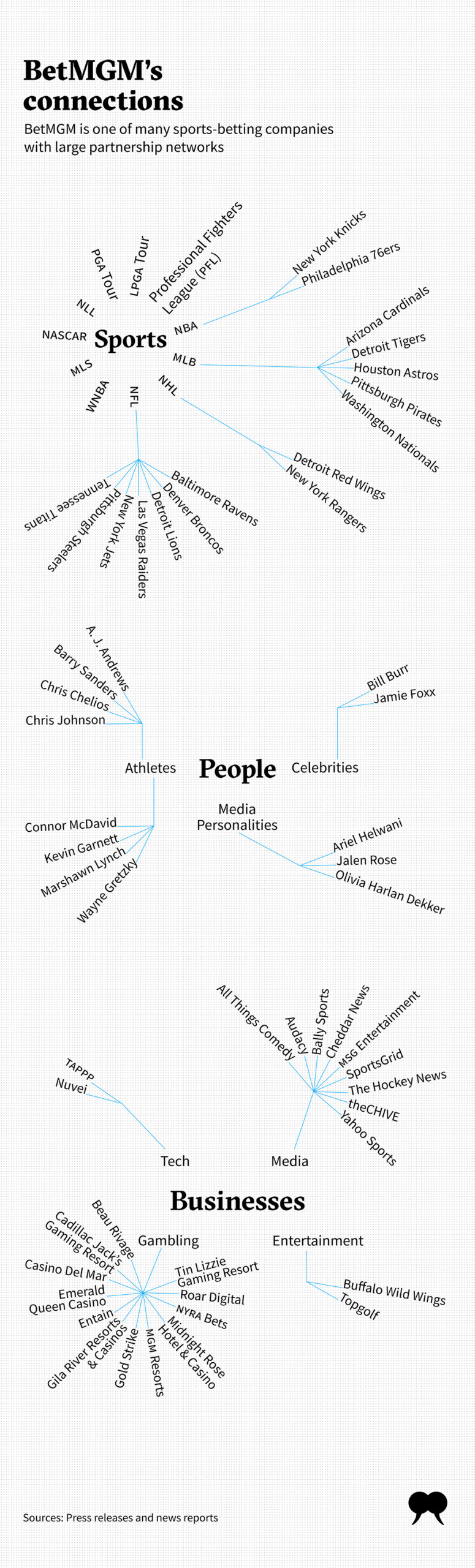

Corny ads like this one are the tip of the iceberg in North America’s new obsession with sports betting. The rapper Drake is posting million-dollar bets on Instagram; influencers are losing thousands on livestreams; Edmonton Oiler Connor McDavid is endorsing BetMGM. Actor Jamie Foxx and athletes such as NFL running back Marshawn Lynch and retired NBA forward Kevin Garnett are also official BetMGM brand ambassadors. Fox Sports has its own betting platform, Fox Bet. Even Disney owns a stake in DraftKings, a sports-betting company, and may be looking to increase its market share. Media personalities and broadcasters are also getting in on the action. Jalen Rose of ESPN is partnered with BetMGM, and Charles Barkley at the cable network TNT is with FanDuel, a sports-betting app. ESPN, CBS, The Athletic, TSN, and others all have official betting partners.

Following in the footsteps of the US and UK, Canada is caught in a gambling gold rush that is penetrating every crack and corner of the sports world. It’s all thanks to recent legislation changes that legalized most forms of sports betting in Canada and created a competitive market for private gambling companies in Ontario. Spectators have been betting on the outcomes of sports for roughly as long as people have been competing in them. But, with the ease of technology and weak advertising laws, these new forms pose serious risks to problem gamblers, sports fans, and to the integrity of sport itself.

It hasn’t always been this way. Since 1985, bettors can fill out “Sport Select” tickets provided by Canadian lottery corporations at convenience stores. The tickets allow for two types of bets: one, called a parlay bet, requires you to bet on the results of at least three different games and get them all right to win; and another, called a parimutuel bet, is one where all bets are placed together in a pool and the winnings are divided amongst those who picked right. By forcing gamblers to play these types of bets, the Sport Select system gives the house a 35 percent edge.

Unsurprisingly, gamblers turned to illegal online sports books. These offshore companies provided single-event betting—on the result of a single game or match—higher payouts, and more interesting prop bets, which are more granular and may or may not directly impact the final score: for example, betting on which specific player will score, how long the anthem will last, or how many times NFL quarterback Peyton Manning will say “Omaha” during the game.

What these offshore systems didn’t provide was tax revenue. Eyeing the potential, the Canadian government decriminalized single-game sports betting on August 27, 2021—nearly two months after the Safe and Regulated Sports Betting Act (Bill C-218) received royal assent. The act allows provinces to dictate who can offer sports betting, the types of bets permitted, and what sports can be bet on.

Single-event betting is now available in every province through provincial lottery systems. Ontario is an exception, as it took a different approach, in 2021, by using its alcohol and gaming commission to manage online gambling through a subsidiary organization called iGaming Ontario. By doing that, it opened the market to private gambling companies on April 4, 2022. It’s the first and only jurisdiction in North America to take this approach. “This is a big experiment,” says John Holden, a sports-law expert originally from Ontario and an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University. Ontario is “bringing these companies over to the white market, the legal regulated market, and really extending an olive branch to them.”

The US saw a similar change nearly five years ago. Single-game wagers were banned in most states until the Supreme Court, in 2018, struck down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, which basically outlawed sports betting in the country, excluding a few states.

After the act was overturned by a 7–2 decision, each state could create its own sports-betting laws. At least thirty of them now have legal gaming markets, and a handful more are predicted to legalize in the coming year. Even states like Texas, which are largely opposed to any form of gambling, are considering legalization.

“There’s been a cultural shift,” says thirty-eight-year-old Steve Delaney, a truck driver from New York state who is recovering from a gambling addiction. “It’s all I see on Facebook; I see billboards all over the place.” He hosts a podcast called Fantasy or Reality? The GPP (short for Gambling Problem Podcast), where he speaks about all things addiction and offers hope to gambling addicts.

More than a year into his recovery, he fell prey to the American gambling market, which is much more developed than Canada’s. He’s worried about his Canadian counterparts being targeted by gambling companies. “It’s become so meshed and ingrained in sports that it seems like it’s a normal thing to do,” he says.

Ever since the infamous 1919 World Series, all major sports leagues have seen gambling as a direct threat to the integrity of sport. In the best-of-nine World Series, Joe Jackson (nicknamed Shoeless Joe) and the Chicago White Sox took on the Cincinnati Reds. Gambling was illegal but widespread, and under-the-table bookies had the Sox as favourites. But rumours floated that the Sox were conspiring to throw the game.

After the Reds upset the Sox to win the series 5–3, evidence was compiled, and an investigation connected the players to various criminal rings. Shoeless Joe and seven other players were charged with conspiring to defraud the public.

After that, the major sports leagues “never differentiated between legal and illegal gambling,” Holden says. “They just viewed it all as bad.”

In 2014, however, NBA commissioner Adam Silver wrote an op-ed in the New York Times calling for the federal regulation of sports gambling. The 518-word article was widely shared and discussed and changed sports leagues’ opinions of gambling. In an email to ESPN, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban said it was groundbreaking. “Leagues for decades were hypocritical about gaming, pretending it doesn’t exist. Adam ended that hypocrisy.”

The NBA realized what everyone knew: making it illegal didn’t stop it from happening. Since then, every major North American sports league, except for the National Collegiate Athletic Association, has come around to legalized betting. According to the American Gaming Association, in 2021, Americans bet a record $57.22 billion (US) on sports, up 165 percent from 2020. And 2022 witnessed the fastest start ever to the first quarter of a year, as sports-betting revenue reached a record $14.31 billion (US), up 26.8 percent from the same period in 2021.

Legal gambling is, however, only a fraction of the global industry. A 2021 report estimated that between $340 billion and $1.7 trillion (US) is illegally wagered every year globally. An American Gaming Association study also found that 52 percent of US sports bettors participated in the illegal market—and that 82 percent of them were surprised to learn they were using illegal websites.

In a speech to the Canadian House of Commons, Conservative MP and former sports journalist Kevin Waugh argued that a legal market would bring in tax revenue and allow governments to “put strict standards and protections in place to protect consumers and offer assistance to those who need it.”

Delaney says that the risks of this new market aren’t being taken seriously. “I feel like you’re opening up the floodgates for the people who may not have gambled in the first place,” he says, “and you’re going to create exponentially larger amounts of problem gamblers.”

The idea that a legalized market is safer rests on the assumption that someone is actively trying to protect gamblers. Who could possibly look out for the gamblers when the same companies that are broadcasting, reporting on, and advertising the games now have a vested interest in encouraging gambling?

Former professional basketball player and popular TV analyst Charles Barkley’s press release from December 2020 is a sample of the media’s promotion of gambling: “FanDuel helps our show be more informative and interactive, and they do it in a way that any knucklehead could understand, so even if your team is down by 20 in the fourth quarter, with FanDuel you’ll have a reason to keep watching.”

With “knuckleheads,” Barkley could very well be referring to what we all know to be the target market of these companies—young men.

It makes sense; for the most part, men watch more sports than women, and bettors consume about twice as much sports content as nonbettors, leading to more advertising revenue for the leagues and higher overall engagement.

A 2016 Australian study found that young men now view sports wagering as a “natural ‘add on’ to sports” and felt social pressure to gamble. It also found that advertisers look to create new subcultures and identities associated with their products. A twenty-nine-year-old respondent in a similar study in 2017 said that advertising “is holding that mirror up to what is good and fun about sport, which is friendship, and comradery, and hanging with your mates, and having a punt while you’re doing that.” Delaney sees many of these impressionable young men come to his support-group meetings. “They feel inadequate with themselves, and their identity becomes being a winner.”

The 2017 study also showed more subtle ways betting is integrated. For example, how commentators spoke about the performance of players and teams through an “odds lens,” always analysing how many points a player will get or using betting terminology in their play-by-play. In Canada, former sports anchors like Cabbie Richards and Dan O’Toole, who were known for antics that appealed to younger viewers, now host dedicated sports-betting segments.

This integration is often more blatant. In a British ad shown immediately before the kickoff of the 2018 England-versus-Colombia football World Cup knockout match, which was seen by 23.8 million viewers, the screen said, “England to score in the first 20 minutes. 4-to-1.” In fact, 17 percent of all World Cup advertising that year was for gambling.

Matthew Young is Director of Research and Evidence Services at Gambling Research Exchange Ontario and a senior research associate at the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. He says Canadian gambling-advertising laws are comparable with those for alcohol advertising, when they could be more like stricter cannabis laws. Cannabis policy bans all promotions of sales and any attempts to shape attitudes toward consumption. “It accomplished many of its goals quite well. We don’t see large upticks in cannabis-related harms, and youth use hasn’t gone through the roof.”

Young is by no means a gambling abolitionist, but he suggests looking abroad to more established betting markets for policy direction. In the Netherlands, for example, recent legislation has put the onus on gambling companies to prove that their ads are not being seen by people under twenty-four. Belgium is set to ban nearly all forms of gambling advertisements. The UK government has launched a law review that will consider banning betting firms from sports sponsorship on team jerseys and lowering online casino stakes.

Societies that take a public approach to health care are quicker to ban advertising in favour of the common good. “Something like this may never fly in the United States; it’s a much more individualistic culture,” Young says. Canada tends to vacillate between public-health and individual-freedom approaches, and different governments will have wildly different ways of addressing gambling policy. For now, Young says, Canadian gambling-advertising policy is all over the place. “Even the Crown corporations that operate gambling are going: ‘This is too much.’”

Advertising isn’t the only problematic development—new game modes have created quicker and more accessible forms of betting. It used to be that gamblers would go to the store to fill out their bets and then wait for the game to end before they got their results. Now you can make your bets on an app and bet throughout the entirety of the game. If you think your team will score in the next five minutes, or there will be a yellow card in the next ten, place your bet. There’s always something to bet on and a way to dig yourself into a deeper hole. This has made sports wagering look increasingly like slot machines, says David Hodgins, a psychology professor at the University of Calgary and a research coordinator for the Alberta Gambling Research Institute. “You get the experience of having losses disguised as wins,” he says. “You can put in $1, and you may get some feedback that you’ve won something in some aspect of your bet, but you’ve lost the other aspects.” For a gambling addict, it’s “essentially like someone moving from smoking marijuana and drinking to injecting cocaine,” Delaney says.

Young sees a perfect storm brewing—increased gambling advertising and availability and a vulnerable population at the tail end of a pandemic. He recalls the early days of the fentanyl crisis. “I’m reminded in the sense that there are a few factors coming together here where I wouldn’t be surprised to see an increase in gambling harm and an increase in people reporting gambling disorder over the next few years.”

Delaney was predated by a mature American gambling ecosystem that overlooked the vulnerable, and he worries Canada is headed the same way. It’s been more than a year since he’s gambled, and he hopes his testimony speaks to others on the same path. Sixteen months ago, he was miserable. “I was living a horrible double life; I was so unhappy, I was so unhealthy, I hated myself. And now I’m happier today than I’ve ever been in my life.”

To get to where he is today, he had to cut sports completely out of his life. He didn’t watch the Super Bowl and doesn’t know who’s in the NBA playoffs. Despite it being such a huge part of his life, he says, he doesn’t miss it much.

“My happiness, my life, my family are more important to me than watching the Knicks or the Mets play.”