The men are skating sitting down. They have strapped themselves into moulded plastic sleds fitted on the bottom with two steel blades, the kind used on ice skates, and they propel themselves using two hockey sticks. Each of these, at about seventy-five centimetres, is one-third the length of a typical stick and equipped with a standard curved blade on one end, for puck handling, and metal teeth on the other, for digging into the ice. Although the game has barely started, the rink already resembles the lunar surface, pockmarked with countless small craters. The men churn like locomotives, their arms the wheels and their sticks the pistons, their raw strength paired with the startling finesse required to stay perched on two narrow blades placed as little as three-eighths of an inch apart.

Some of the men have stumps rather than legs or feet, some have one leg, some have legs that are disproportional, and some have no outward sign of disability. Most sit with their legs or stumps straight, in line with the metal frames that stretch forward from their sleds, although one of the goalies—the Canadian, Benoit St-Amand—has his one full leg crossed in front of him. (The goalies carry just one stick, and their skate blades are set wide apart so they can stay upright.) The men play rough. Because they are at ice level, they check each other straight into the boards rather than into the more forgiving tempered glass above, and when this happens the sound of plastic, flesh, and bone against fibreglass is awful, something between a clatter and a dull crunch.

The sport is called sledge hockey. I am watching the 2013 World Sledge Hockey Challenge at the MasterCard Centre in Toronto, Ontario, last December. The Canadian national team is up against Russia in a round robin game to determine standings for the semifinals. The day before, Team Canada easily defeated South Korea, 5–2. This is the last international tournament before the 2014 Paralympic Games in Sochi, Russia. While sledge hockey is probably the most popular sport at the Winter Paralympics, few people, I’ve discovered, have heard of it. Today the stands are more or less full, because masses of schoolchildren have been bused in. Most of them are enthusiastic, cheering loudly when Canada scores, although some are sullen and unresponsive in the manner of teenagers, leaving to buy french fries or watch the Maple Leafs practise in the next rink over. On two platforms, accessible by ramp, a dozen or so spectators in wheelchairs have gathered.

Sledge hockey, invented in Sweden in the ’60s, is played by people with lower-body disabilities such as leg amputation, paraplegia, or partial paralysis. The rules are almost identical to those of traditional hockey, which sledge players call “stand-up.” However, because the athletes can only use their arms for propulsion, puck handling, and shooting, the sport is in many ways more physically demanding. It is played full contact, although T-boning another player with one’s sledge is illegal. “A lot of guys use those metal picks on the end of the stick to stab guys,” says Greg Westlake, the twenty-seven-year-old Team Canada captain. “I’ve had stitches. I have scars all over my rib cage. I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily a more physical game, but it might be a dirtier one.” During a US-Canada showdown at the 2009 Hockey Canada Cup in Vancouver, a massive skirmish erupted after an American player checked the Canadian goalie with just 1.7 seconds left on the clock. The fight has drawn over 266,000 views on YouTube.

Here at the World Sledge Hockey Challenge, the level of play is swift, smooth, and brutal. The men move in pirouettes, twisting at the hips to carve from side to side and brawling in dog pile fights. (“These teams do not like each other,” I overhear a Hockey Canada official say.) They are adept at catching passes under their sleds, between the front-end skid and the rear blades, which seems like an impossible manoeuvre. The score inches upward: 1–0 Russia, then 1–1, then 2–1 Canada, 3–1, 3–2, 4–2, 5–2, until Canada emerges victorious at 5–3. With my face at the glass, I watch a defenceman, Adam Dixon, shake his head, wide eyed and stunned, after a particularly big hit. Mostly, though, I watch another player, number 26. He is not flashy—he earns no points in this game, and is overall a lower scorer than the other Canadian forwards—but he is still domineering, intimidating, and, at six feet and 184 pounds, one of the largest men on the ice, sitting tall and broad in his sled. His name is Dominic Larocque.

Larocque doesn’t remember the explosion that took off most of his left leg on November 27, 2007. He recalls going to sleep around 2 a.m., after a routine foot patrol with his unit in Zangabad, in the Panjwai district of Afghanistan. He remembers waking up a few days later in the hospital at Kandahar Airfield, and that’s about it. When reminded of things he said or did in the interim, he thinks he has brief flashbacks, but he also believes he might be projecting. “When they told me, I had images in my head that were like, okay, that makes sense,” he says. “But if they’re real or if they’re from a movie—I can’t tell the difference.” What he does know is, on that November morning he was riding in an LAV III down Route Foster with five other soldiers from the Royal Twenty-Second Regiment—the driver, the crew chief, and the gunner in the front, Larocque and two other infantrymen in the back—when they drove over an improvised explosive device. The IED tore into the rear of the light armoured vehicle with such force that it blasted him up and out before he slammed back onto the roof. One of his fellow passengers in the back was thrown clear, fracturing a vertebra but escaping permanent spinal cord damage, while the other remained inside and lost both of his feet.

Larocque was twenty years old and had been in Afghanistan for four months. He had joined the army at eighteen, straight out of high school (his grandfather served in the same regiment, nicknamed the Van Doos, an anglicization of vingt-deuxième). By the time he came to at the airfield, his left leg was already gone from the knee down. It was mangled in the explosion, not blown clean off, but it had become infected and the doctors were forced to amputate. After a few hazy, sedative-filled days, he was flown to a military hospital in Germany and then to the Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus in Quebec City. In January, he was transferred to the Institut de réadaptation en déficience physique de Québec to begin rehabilitation. Over 2,000 Canadian soldiers were wounded during the war in Afghanistan. With Larocque at the rehab centre were his two fellow soldiers who were injured in the Route Foster explosion, along with two others who had been hurt in a similar attack a week prior, both of whom had lost a leg; a third man had died.

During his eight months of recovery, Larocque swam, exercised on a stationary bicycle, and lifted weights, training his body to work in its new form. The greatest challenge, though, was learning to walk with a prosthesis. He was fitted with a C-Leg, a $45,000 system powered by sensors and microprocessors that adapts its swing to the user’s gait, speed, and position. Getting used to a prosthesis requires a delicate combination of coordination, equilibrium, strength, and sensory awareness; the slightest change in elevation can send the wearer tumbling. “Normal people walk without thinking about it,” Larocque tells me over burgers in Quebec City, “but us, we always have to think about walking.”

He had chosen the infantry because he hoped to become a search and rescue technician, but now that was off the table. He began working as a graphic designer, creating brochures and posters for the military, but he wanted to do something active. As a child growing up in Valleyfield, Quebec, he loved soccer, football, lacrosse, and especially hockey, playing centre on his high school team, the École de la Baie-Saint-François Broncos, and for the local Valleyfield Braves. In the spring of 2008, while still in the hospital, he watched a telecast of the International Paralympic Committee Sledge Hockey World Championships, held in Marlborough, Massachusetts, where Canada eked out a 3–2 victory over Norway. He was intrigued but knew nothing about the game or anyone who played it. Then, in the fall of 2009, he caught a game featuring Montreal’s sledge hockey team, the Transat, and attended a clinic in Quebec City where the team’s players outlined the basics and showed him how to use the equipment.

Larocque started buying gear, including a Razor sled made by Unique Inventions. On weekends, he travelled to Montreal to practise with the Transat, and during the week he used the rink at the Valcartier military base, northwest of Quebec City, with friends who played stand-up. In early 2010, Soldier On, a government organization that helps disabled veterans get involved in sports, arranged for some twenty wounded military personnel, including Larocque, to attend the Paralympic Games in Vancouver, where they toured the locker rooms and played sledge hockey on the Olympic ice. Although he enjoyed the game, he considered it a marginal sport, until he watched Canada play Norway in the bronze medal game before a packed arena. Canada lost, but that hardly mattered. “The full arena, the fact that I’d already played, that I was good, that I had a good sense of hockey, that it’s our national sport—all of that directed me here,” he says. He had made sledge hockey his game.

In 1943, the British government asked Oxford neurologist Ludwig Guttmann, a German Jew who had fled the Nazis four years earlier, to become the director of the National Spinal Injuries Unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. After the war, the medical establishment began exploring novel ways to rehabilitate the unprecedented number of wounded soldiers. Several organizations already existed for athletes with disabilities, and in 1924 Paris had hosted the first International Silent Games (the precursor of today’s Deaflympics). Guttmann and the paraplegics in his unit at Stoke Mandeville tried out a variety of games—darts, snooker, wheelchair polo—before settling on archery. On July 29, 1948, opening day of the Fourteenth Olympiad in London, he organized a modest competition with a nearby hospital in which sixteen veterans participated. Guttmann dreamt, he wrote later, that “the time might come when this event would be truly international and the Stoke Mandeville Games would achieve world fame as the disabled men and women’s equivalent of the Olympic Games.”

The event grew from there, adding more sports and teams each year. Guttmann, whose love of the spotlight was matched only by his love for himself, never missed a chance to compare his games to the Olympics, even expressing the hope, reportedly, that the Olympics would someday include athletes with disabilities. Then, in 1960, just a few weeks after the Olympics in Rome, the Stoke Mandeville Games—featuring some 400 participants from twenty-three countries—took place in the same city. Although they were not named as such and had yet to establish any formal collaboration with the Olympics, these were the first true Paralympics. (The word was coined as a portmanteau of “paraplegic Olympics,” but once the games opened up to athletes with other disabilities the prefix’s official meaning changed to “parallel.”)

In 1964, the Stoke Mandeville competition followed the Olympics to Tokyo, but for the next two decades accessibility issues and official disputes kept the two events apart. The turning point came in 1988, at the Summer Games in Seoul (the first Winter Olympics for the Disabled, as they were called, were held in Örnsköldsvik, Sweden, in 1976). That year, the games were rebranded as the Paralympics, and it marked the beginning of a closer relationship between the International Paralympic Committee and the International Olympic Committee, which continues to this day. The Paralympics are now the world’s second-largest multi-sport event, held a few weeks after each Olympics. At the London 2012 Summer Games, 4,237 athletes with disabilities from 164 countries competed in 503 medal events across twenty sports. Historically, the Winter Paralympics have been smaller than the Summer, due in part to the difficulty of adapting winter sports for athletes with disabilities. At the Paralympic Games in Sochi, an estimated 700 participants from forty-five countries will compete in seventy-two medal events across five sports: alpine and cross-country skiing, biathlon, wheelchair curling, and sledge hockey.

Although Guttmann is often described as the father of the Paralympics, he was also notoriously petty and autocratic, ordering competitors to play certain sports against their wishes, insisting on the continued use of the Stoke Mandeville name long after the games stopped being held at the hospital, and dismissing non-athletic disabled people as “useless and hopeless.” Danielle Peers, a disability studies scholar at the University of Alberta and a former Paralympian, says, “He was hugely paternalistic, hugely controlling, and absolutely clear in his writings that athletes should have no say. It was very much a medical model: ‘We’re the experts.’”

Part of Guttmann’s ambivalent legacy is the Paralympics’ complex, controversial classification system, under which athletes are grouped according to the nature and extent of their disabilities, with many sports having multiple classes. (The IPC identifies ten eligible “impairment types,” including limb deficiency, hypertonia, and visual impairment.) Whereas sledge hockey is open to anyone with a lower-body disability that prevents normal skating, many other sports hold separate events for various impairment types. So, for example, in the 100-metre dash ambulatory sprinters don’t compete against those in wheelchairs, and all are evaluated by a classification panel. For visually disabled competitors, this simply means submitting to an ophthalmology exam, while for others it involves more rigorous testing and observation. Then there is the confusing points system: in some sports, a formula assigns a total point value to each person’s performance, so those with more serious disabilities are less disadvantaged, which means that an alpine skier who finishes last could still win gold.

The system remains a constant point of contention. “It’s very uncomfortable for the athlete, in that an expert comes along and determines your capacity and has a massive impact on your ability to play,” Peers says. “Often, the experience is alienating and medicalizing, and sometimes arbitrary.” Last year, at the Sledge Hockey World Championships in Goyang, South Korea, a Canadian player who had been deemed eligible to compete in previous tournaments failed to qualify and was sent home. Sometimes, to gain an edge, competitors have even pretended to be more disabled than they are. Following the 2000 Paralympics in Sydney, the second games in which people with intellectual disabilities were allowed to participate fully, a Spanish basketball player revealed that his gold medal–winning team consisted mostly of non-disabled athletes who had faked their low IQ results.

Among people with disabilities, considerable disagreement exists over whether the Paralympics represent mere tokenism, an opportunity for non-disabled spectators to gawk at strange bodies, and an over-commercialized gift to sponsors eager to gain recognition as good corporate citizens. Many critics insist that running the Paralympics as a separate event consigns it to second-rate status. “By sanctioning a parallel system the Olympic Movement has failed to include disabled athletes in elite international competition and institutionalised exclusion as a taken for granted phenomena that is beyond challenging,” the scholars Peter Kell, Marilyn Kell, and Nathan Price write in The Paralympic Games: Empowerment or Side Show? Instead, they argue, disabled and non-disabled athletes should compete at the same games, side by side.

The south african sprinter Oscar Pistorius was born in Johannesburg in 1986 with fibula hemimelia, and when he was eleven months old both of his legs were amputated below the knee. Still, he became an athletic child, taking up running with the help of racing prostheses, which curve elegantly to the ground and earned him the nickname Blade Runner. He went on to compete in both able-bodied and disabled events, winning gold and breaking records in several championships.

Pistorius hoped to compete in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, but he came under scrutiny when the International Association of Athletics Federations introduced a ban on “any technical device incorporating springs, wheels or any other element that provides the user with an advantage over another athlete not using such a device.” IAAF data suggested that his artificial limbs wasted considerably less energy than flesh and blood ones, making him ineligible. He launched an appeal, and his lawyers furnished independent tests, arguing that the IAAF had failed to take into account the drawbacks of his double amputation. In the end, the Court of Arbitration for Sport agreed. Pistorius did not participate in the 2008 Games, but only because he failed to make the minimum qualification time. When he successfully qualified in 2012, he became the first amputee runner to do so, and although he didn’t win a medal in London he carried his country’s flag during the closing ceremonies. At the Paralympics a few weeks later, he won two golds and a silver.

Then things went dark. In the early morning of Valentine’s Day 2013, Pistorius fired four shots from a 9 mm pistol through the bathroom door of his Pretoria home, killing his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp, who had locked herself inside. His lawyers insist that he thought she was an intruder and that he fired in self-defence, but the prosecution argues that the shooting was premeditated. (His trial is set for March, overlapping with the Sochi Paralympic Games.) Before this ugly turn, however, he inspired a new public conversation about sport and disability. While he was not the first disabled person to compete at the Olympics, he was the first to so visibly employ technology and level the playing field. All athletes are, in a sense, cyborgs: they exist on a continuum, from the shot putter and his shot, to the archer and her bow, to the sledge hockey player and his sled. So where exactly do officials draw the line between Usain Bolt’s custom-made Puma spikes and Oscar Pistorius’s custom-made Cheetah prostheses?

Pistorius, of course, is relatively able bodied. Many Paralympians have more severe disabilities, and an athlete with cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis will not be as familiar to mainstream fans as Pistorius. Still, however imperfectly and temporarily, he challenged public perceptions of the archetypal human form. The issue was not that he couldn’t keep up with able-bodied opponents, but that he might be too good, too fast, too strong.

With Pistorius out of competition, the conflict over his Olympic eligibility has subsided. However, advances in prosthetics and accessibility technology mean there will be others like him who complicate the division between able-bodied and otherwise. Meanwhile, disabled sport appears headed for a tipping point: both the Beijing and London Paralympics shattered attendance records, with 3.4 million spectators at the former and $70 million in ticket sales at the latter. Legitimate questions remain about whether attendees showed up for the feel-good atmosphere or the athleticism. Still, if any game has the power to push disabled sport into the mainstream—in Canada, at least—it’s sledge hockey, with its potent combination of familiarity and toughness.

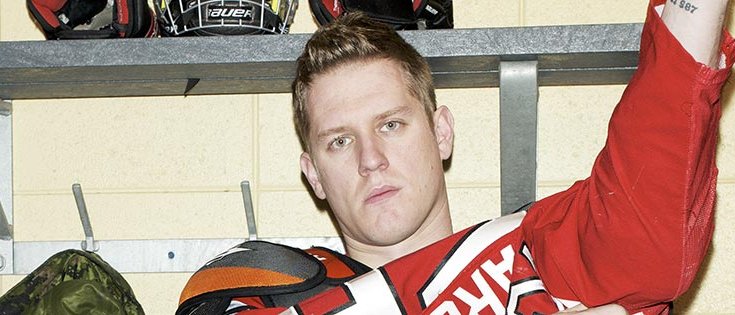

Soldiers often look like soldiers, and Larocque is no exception. He has close-cropped dirty-blond hair, pale green eyes, a square jaw—the whole deal. He is muscular, the slight hitch in his gait from his prosthetic leg hardly diminishing his imposing presence. He drives a white Mitsubishi SUV and wears Ray-Ban aviators, tight Parasuco T-shirts, and cargo shorts. On his upper left arm, he has a tattoo of geodesic shapes and vaguely Aboriginal masks, inspired by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s.

In the spring of 2010, at the Défi Sportif (an annual Montreal event for athletes with disabilities), a few recruiters saw Larocque play sledge hockey and invited him to try out for the national team. That September, he attended the selection camp in Petawawa, Ontario. “You could see right away that because of his hockey background he had some real good instincts,” says head coach Mike Mondin. “The way he could see the ice real well, the way he anticipated the play, his checking skills—you could see that the potential was there.” After the camp, the coaches sat Larocque down in a conference room and told him he had landed a spot on the team. He spoke little English, though, so he simply got up and walked out of the room, his face impassive. “We kind of looked at each other and said, ‘I’m not sure if he really understood that he made the team,’” Mondin says. The manager, who spoke French, chased Larocque down in the hallway and clarified that he had made the cut, despite only having played since January. “After nine months, I joined the national team,” Larocque says. Then, grinning and switching to English, he says, “Not too bad.” (Although his teammates say his English has improved, he and I spoke almost entirely in French.)

He quickly distinguished himself on the team, which consists mostly of seasoned players. Greg Westlake, the captain, has played sledge hockey since he was fourteen. “I always like lining myself up against him, because he loves throwing hits, I love throwing hits, and it’s just good work,” he says of Larocque. “I’ve definitely peeked at the other team’s line in practice and made sure that I’m in line to face him. I don’t even know if he knows that I do that.”

If sledge hockey is difficult to master, it could be because it imports, almost wholesale, the rules and ethos of stand-up hockey but requires a substantively different skill set. As a child in Oakville, Ontario, Westlake (whose feet were amputated when he was eighteen months old because of a birth defect) played regular hockey using prosthetic legs but, he told me, “I was never going to make the NHL on two artificial feet.” He wanted to play at a high level, so he decided to switch to sledge hockey, travelling to nearby Mississauga to practise with a club team. “I just figured I’d get out there and be one of the best guys on the ice, because I’d played stand-up,” he says. “When I got on the ice and there were people who off the ice were in wheelchairs or missing a limb, and they were way better than me my first time—I was just blown away by how good these athletes were, and it sold me on the sport.”

Because the sport is so small and specialized, it offers few equipment options. The sleds cost between $549 and $749, and Unique Inventions—which is based in Peterborough, Ontario, and supplies the Canadian team—is the only commercial manufacturer in Canada. The company also outfits the national teams of South Korea, Japan, Germany, the US—even Sweden, birthplace of the game. “That’s how we manage to do it,” says founder Laurie Howlett. “It’s not a big market, but when you’re shipping all over the world it’s enough to keep you going.”

Sledge hockey takes an added toll on players’ bodies, not least because of the sheer difficulty of being disabled in a world designed for able-bodied people. For those who use wheelchairs, repeatedly hoisting themselves on and off an inaccessible bus, or in and out of an inaccessible rink, becomes a gruelling upper-body workout. Then there are the injuries. “Any of those hits you see, players going into the boards—some have said it’s like hitting a brick wall at full speed,” Mondin says. As well, the sleds are difficult to keep under control. At a provincial league game in Montreal, I saw one player hit another from behind with his front-end foot guard, and his opponent tilted back and up like a drawbridge before slamming down to the ice. Larocque accidentally dislocated Westlake’s jaw once, after losing his balance and hitting his teammate in the chin with his sled’s foot guard.

The Canadian team has recorded some important recent victories. Last April, at the world championships in Goyang, it went undefeated, ultimately triumphing over the US. Then, in August, at the Four Nations tournament in Sochi, it narrowly defeated Russia, 4–3, in a shootout during the finals. Everyone agrees that Russia will be the team to beat at Sochi, even though it has never had a national team. “They’ll be the toughest ones, and the team has only existed for three years,” Larocque says. In 2010, Russian representatives visited Ontario to study the game and ordered dozens of sleds from Unique Inventions. Unlike the Canadians, who are scattered across the country and practise together for just one a week each month, the Russians are brought together for an intense training schedule. As the Olympic host and a global hockey power, Russia takes the sport seriously, but after an embarrassing fourth-place finish at the Vancouver Paralympics Canada also has something to prove. “I want to win a gold medal,” Westlake says. “And you can’t play hockey for Canada and not go to a tournament expecting to win.”

Afew days after Canada defeats Russia at the World Sledge Hockey Challenge, I return to the MasterCard Centre for the gold medal game. It’s Canada against the US—still, for the time being, the two best sledge hockey teams in the world. The Canadians have not lost a single game during this tournament, and the Americans have only lost one, to Canada in a previous round. Members of the vanquished Russian and South Korean teams watch from wheelchair-accessible platforms, and red Team Canada jerseys fill the stands. The US players’ sleds are flashy, covered in a mosaic of American flags. Next to me in the press box, a Hockey Canada official quietly whistles along to Smash Mouth’s “All Star.”

The game moves furiously. When the men check each other at centre ice, they go sprawling, spinning like tops. I wonder, not for the first time, at their ability to propel themselves with one stick while handling the puck with the other, an unfathomable feat. Nine minutes into the first period, Adam Dixon scores, with an assist from Larocque. Later, Westlake and another forward, Billy Bridges, score just thirty-two seconds apart. Larocque plays hard. He scrabbles in the corners, slipping onto his back and twisting, his sled slicing through the air. At one point, an American player, Andy Yohe, skates into him and simply bounces, a meteor glancing off a planet.

Watching them reminds me of the term “super-crip,” which disability studies scholars use to describe a certain kind of person, as portrayed in the media. Super-crips have scraped the lows of their disabilities but have come out the other side as better people. They teach everyone to be grateful for their privileges, not to sweat the small stuff. Athletes are particularly susceptible to such characterization, as I discovered writing this story. Before his fall from grace, Oscar Pistorius was the ultimate super-crip. The inverse is the passive, vulnerable vegetable, with little room for nuance in between. The problem with the super-crip narrative is that it reduces people to their disabilities and places the onus for change on the individual so that he, rather than the society around him, must adapt.

For able-bodied people like me, it can be difficult to watch athletes with disabilities without falling into well-meaning discrimination. I know I am writing about Larocque because he is a war veteran and a hockey player and handsome and a literal poster boy who appears on posters for Soldier On. He fits a certain vision of what a Paralympian should be. In January 2012, the Canadian Paralympian Committee launched a YouTube campaign, Super Athletes, featuring Larocque and several others. In the videos, a gravelly baritone voice holds forth on each competitor’s skills as cinematic music swells. Any team might commission this kind of overdramatic advertising, and it is gratifying to see athletes with disabilities presented as champions above all. Still, it’s hard to escape the sense that something is off—that these Paralympians are considered admirable not for their accomplishments on the field, but because of what they have overcome off it. As the men race across the ice, I wonder if it’s possible to observe them without looking for more than what is there—how I might find grace and power in the game without reducing the players to vessels of inspiration. When mainstream conversations about athletes with disabilities simultaneously recognize their difference and greet them as competitors first, something will have shifted for the better.

The game is scarcely a contest. Although Josh Pauls of the US scores in the second period, it will be his team’s only goal. During the final minute, the play grows more frenzied as the Americans scramble to close the gap and the Canadians maintain their advantage, but there is no hope for an upset. When the whistle blows, the rest of Team Canada pours onto the ice and piles into the net, flinging off their helmets, ecstatic and smiling. After the usual rituals—the gold and silver medals, the anthem, the lifting of fists and sticks to the stands—the players glide off the rink. Outside the dressing room, they unstrap themselves from their sleds. Some, like Larocque, immediately put on their prosthetic legs, some hoist themselves into wheelchairs, some hop on one foot, and some get up and walk, as the locker room door swings shut behind them.

This appeared in the March 2014 issue.