In 1954, soon after publishing the first volume of his Lord of the Rings trilogy, J.R.R. Tolkien received a letter from Peter Hastings, manager of a Roman Catholic bookshop in Oxford. Hastings suggested that Tolkien was “over-stepping the bounds of a writer’s job” in creating Middle-earth, arguing that the author should only write about metaphysical phenomena that God himself used. Tolkien, a devout Catholic, responded with an impassioned defence: “Are there any ‘bounds to a writer’s job’ except those imposed by his own finiteness? ”

His novels, about a gaggle of furry-footed hobbits caught up in a heroic quest, were a prototype of the high-fantasy genre: books set entirely in an imagined universe. Unlike portal fantasies (in which characters travel from our world into another, as in the Chronicles of Narnia) or urban fantasies (in which supernatural elements are introduced into our world, as in Twilight), high fantasies integrate gods, magic, and sorcery into the metaphysics of the imagined place—in this case, Middle-earth, a bucolic, village-dotted countryside that suspiciously resembles medieval England.

Sixty years later, Tolkien’s wildly influential series has spawned enough high-fantasy descendants to fill a library, among them Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain (set in a Wales-like nation ruled by a Sauron-like arch-villain); Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series (whose world is powered by the titular seven-spoked wheel); Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle (set in a pre-industrial, wizard-filled archipelago); and Terry Pratchett’s Discworld (in which a Frisbee-shaped universe balances on the backs of four elephants standing on a turtle).

Guy Gavriel Kay is the most visible Canadian contributor to the genre, having published high-fantasy novels for more than twenty years, including Under Heaven and such bestsellers as the Fionavar Tapestry and the Sarantine Mosaic series. He takes the notion of world building to its next logical conclusion, spinning intricately detailed, laboriously constructed, historically based dreamscapes. In April, he released River of Stars, a fantasy novel that models its imagined Kitai empire on the real-life Chinese Sung dynasty and relegates magic and sorcery to the background.

The genre, long marginalized to the Dungeons and Dragons set, recently bounded into the mainstream, courtesy of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, an epic heptalogy that has sold 20 million copies in North America and, in 2011, was adapted into Game of Thrones, a sex-and-swordfight series for HBO. Critics have praised Martin’s books for their gritty realism (an odd compliment for a fantasy series) and complex multi-character perspectives.

From where I sit, A Song of Ice and Fire’s popularity has little to do with the writing, which is no better or worse than that of most fantasy series. Rather, it owes its success to changing readership demographics, the disappearing boundaries between high- and lowbrow culture, and, of course, the power of the Internet to disseminate the gospel of Martin. This holds true for the entire genre. Its fans—no longer cloistered in their bedrooms, reading about knights, wizards, and trolls by flashlight—have come to control the conversation, in the academy and in popular culture. And as the associated stigmas have disappeared, the speculative genres’ multi-tentacled influence has exploded.

In the most popular works, though, the term “high fantasy” is something of a misnomer: all of these invented worlds look uncannily like our own. The topography mirrors that of earth: oceans, mountains, forests, deserts. Same goes for the inhabitants, who are humanoid and near-universally white, living in societies that are dichotomized into monarchies or pagan tribes. Even the names are practically the same; Martin’s central characters have vaguely English names such as Eddard, Catelyn, and Joffrey.

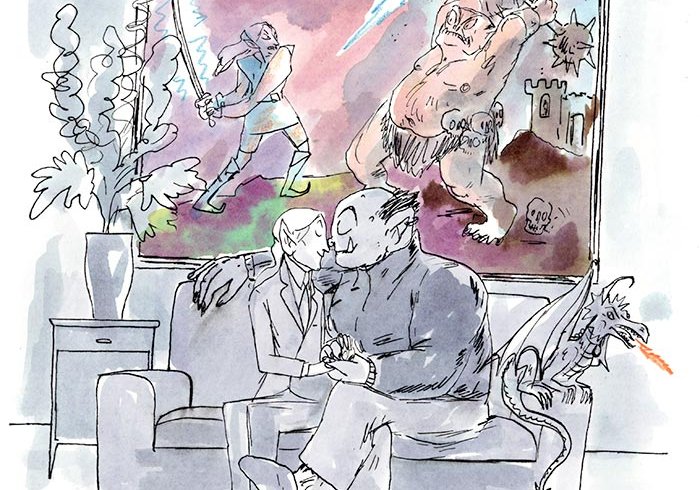

Rather than taking advantage of the imaginative freedom fantasy affords by devising outlandishly inventive worlds, most writers recreate tweaked variations of the past. “High fantasy” has become a synonym for “historical fiction plus dragons.” Critic Kathryn Hume once said the impulse behind all literature is either mimetic (imitating reality) or fantastic (altering and changing it). We have reached the point where the former has cannibalized the latter. Instead of an expression of what could be, fantasy has become a regression into what once was.

At first glance, most high-fantasy landscapes resemble Medieval Times theatre, with knights in armour, peasants in burlap smocks, and rustic villages. The Pre-Raphaelites, known for their fetishization of pre-industrial romance and myth, were the first to take fantasy fiction in that direction. In 1896, William Morris, the ultimate Victorian Renaissance man (craftsman, socialist, carpenter, poet, painter), published The Well at the World’s End, about a young prince on a quest for immortality and heroism. The gloomy-eyed Scottish preacher George MacDonald also drew on medieval legend for his 1858 novel Phantastes, which introduces a world called Fairy Land inhabited by giants and knights.

MacDonald had an indelible impact on Tolkien, who mined Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon folklore and history. His hobbits—Frodo Baggins, his uncle Bilbo, and his best friend (and possible boyfriend), Sam—live in charmingly cluttered underground dwellings and consume traditional English fare like cakes and rabbit stew. On their journey through the Britannic forests and knolls of Middle-earth, where the magical co-exists with the mundane, they encounter knightly heroes, sprightly elves, grumpy dwarves, and evil sorcerers. Tolkien derived his languages—Elvish, Adûnaic, Rohirric—from ancient Germanic, Celtic, and Scandinavian runes, as well as Anglo-Saxon.

For Tolkien, a medievalist and philologist at the University of Oxford, the Middle Ages served as an entry point into a British mythos that revolved around the nation’s land and languages. In a letter to a publisher, he explained that his mythology should be “redolent of our ‘air’ (the clime and soil of the North West, meaning Britain and the hither parts of Europe)”; that it should have “the fair elusive beauty that some call Celtic”; and that it “should be ‘high,’ purged of the gross and fit for the more adult mind of a land long now steeped in poetry.” The medieval era provided a blank slate for Tolkien’s romantic vision, untainted by industrialization and scientific reckonings.

After The Lord of the Rings was published in the ’50s, the copycats descended in droves. “Writers were trying to evoke a sense of the exotic, a sense of wonder,” explains Allan Weiss, a professor at Toronto’s York University who studies speculative genres. “You would provoke your reader’s imagination by providing a sense of an other land, and then you would do the same with the past.” Setting fantasy in a medieval context evoked the romance we associated with the Middle Ages, though authors tended to cherry-pick what they wanted to romanticize (the pristine landscapes, the simplified religious beliefs, the monarchical social structure) and what they wanted to discard (plagues, religious crusades, and torture devices).

Fantasy should be the freest of genres; authors might alter the laws of nature, invent species, and conjure entire metaphysical universes. But its limits are quite binding—restrictions imposed not necessarily by the writer, but by the reader, who expects familiar signposts. “You’re trying to give people a world they can see, so you pull elements from your own world to give it some grounding,” Weiss explains. “It’s a question that often comes up in science fiction: can you create a wholly alien alien if you can’t conceive of one? ” Through fantasy, the past becomes a knowable conduit through which that elusive sense of wonder can be achieved and fantastical whims can be indulged.

Fantasy also fulfills more nefarious desires. Many novels use backward settings as an excuse for backward attitudes toward women, minorities, and poor people, idealizing hierarchies stratified by class, gender, and race. Tolkien, for one, constructed a male-centric, lily-white universe in which race—whether hobbit, elf, orc, or dwarf—determines character, and the noble elves and the humble hobbits are stacked on a vertical class hierarchy. Tolkien lived at the dawn of the modern age, with two world wars, nihilism, and industrial innovation decimating the order of his universe. While his contemporaries, devout modernists like Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and James Joyce, flicked a middle finger at the old literary traditions, Tolkien used The Lord of the Rings to return to a time of simplicity, civility, and moral absolutism.

These retroactive social structures have reverberated across the genre. The Wheel of Time, Robert Jordan’s fourteen-book series, essentializes men and women across a stark gender line: both sexes have separate functions, in society as well as in the balance of Jordan’s spoked universe. Women can channel saidar, described as a gentle river of strength, while men channel saidin, a raging, stormlike source of power. (Women also get spanked a lot.) Meanwhile, Joe Abercrombie, another bestselling high-fantasy author in the UK, writes about a murky medieval world in which a dark-skinned people called the Gurkish terrorize the white protagonists with zombie soldiers.

George R.R. Martin may be the worst offender, crystallizing all of these problematic structures in his Song of Ice and Fire books, where women are either manipulative shrews or subjugated whores. The exception is the princess Daenerys Targaryen, who is nonetheless powerless without her husband (who rapes her) and her pet dragons (who protect her). Furthermore, Martin’s tales draw on colonial racial stereotypes, via a barbaric, swarthy race called the Dothraki, who eat raw horse hearts, rape women with abandon, and provide a scathing contrast to the cool, calculating white Machiavellians grappling for the crown.

History allows fantasy writers to access values and traditions from the past, albeit a past in which dragons and elves are a common sight. And at a time when white men are losing power—to women, minorities, immigrants, and even machines—an alternate reality in which they still reign supreme can be an appealing fantasy indeed.

By contrast, Guy Gavriel Kay uses the limits of fantasy to his advantage. His novels blatantly model their fictional settings on real-world societies: Spain during the Crusades in The Lions of Al-Rassan, the Byzantine Empire in the Sarantine Mosaic, and Sung dynasty China in his latest book, River of Stars.

“I don’t even write high fantasy,” he told me, though the nature of his works—magic-tinged secondary worlds—says otherwise. But I see what he means. His meticulously constructed lands remain ultra-faithful to their source material, right down to the wall hangings of twelfth-century Kitai, the hippodromes of ancient Sarantium, and the military regiments that storm Al-Rassan. He limits the magic to what the characters might have believed in, which results in literature that feels more like historical magical realism than high fantasy. If a Taoist priest exorcises a demon from a young woman’s body, it is based on Kay’s knowledge that the ancient Chinese believed in and used this kind of magic.

He grew up reading historical fiction by Geoffrey Trease, Rosemary Sutcliff, and Dorothy Dunnett, and first angled into fantasy in 1974, when Christopher Tolkien recruited him to help edit The Silmarillion, his father’s unfinished almanac of Middle-earth. Ten years later, Kay published his first novel, a straight-up portal fantasy called The Summer Tree. It would become the first volume of the Fionavar Tapestry, a trilogy that drew on Celtic, Arthurian, and Norse myths, among others, to upturn expectations of what fantasy could do. “It was a backlash to the backlash,” he explains, referring to the move away from high fantasy in the ’80s, in favour of grittier urban fantasies.

After Fionavar, he wrote his first work of historical fantasy, Tigana, set in a slightly altered version of medieval Italy. It was a loophole for an ethical quandary: he wanted to write historical fiction but felt squeamish about attaching imagined desires and impulses to real figures. Instead, he invented new worlds, just different enough from their inspirations that he could write unbound by the rules of history. “Those shifts gave me tremendous creative freedom and released me from this anxiety I feel about saying, ‘I know what Henry VIII’s favourite position in bed was.’” It creates a winking camaraderie between writer and reader, acknowledging that neither will ever know what really happened.

Like Kay, other authors recognize that high fantasy thrives on familiarity, that it always fulfills a desire for a pre-existing world, albeit a disappearing one. Moreover, they have turned those yearnings on their heads, delivering more progressive alternate realities. The people of the primary race in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle have copper-brown skin, while the villainous Kargs are white-blond and pale. And Mercedes Lackey and Marion Zimmer Bradley incorporated matriarchal societies into their high-fantasy works. In Lackey’s case, her Valdemar books concern a goddess and a queen who reign over male peons; while Bradley cast the Arthurian fables as feminist legends, beginning with The Mists of Avalon.

Unlike these other fantasy heretics, who still insist that their worlds are purely fantastical, Kay dispenses with the straw man theory that fantasy is an escape from the real. He uses his novels to reveal specific moments in history, highlighting the complexity of their social structures rather than obscuring them in the soft focus of fantasy. “The past is both astonishingly different and startlingly similar,” he explains. “I like to make the two points, sometimes in the same paragraph, so readers get both the strangeness of the past and the eerie familiarity of human behaviour across centuries.” The evolution of high fantasy over the past century has affirmed that there is no such thing as an unknowable world, and Kay’s books help us know ours a little better.

This appeared in the June 2013 issue.