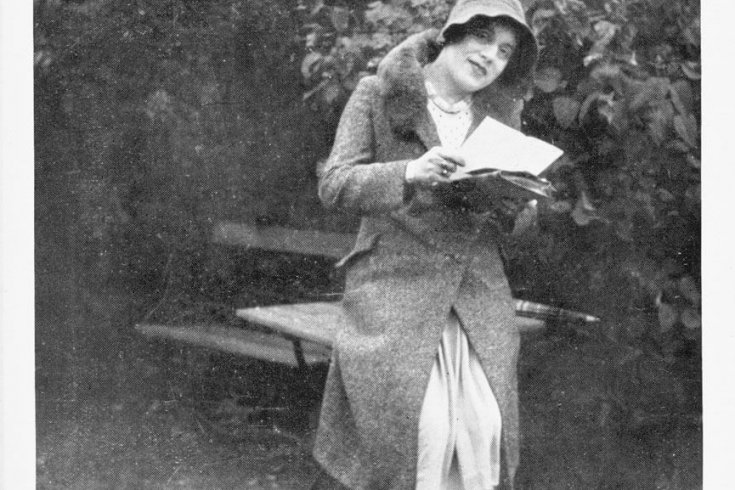

Nine decades before the world knew the name Caitlyn Jenner, they knew Lili Elbe—a successful Danish landscape artist who achieved fame as a biologically male artist before transitioning to her lifelong female identity. The publication of Elbe’s 1933 autobiography, Man Into Woman, is considered a landmark in the history of transgenderism. In 2000, a fictionalized account of Elbe’s life, The Danish Girl, became a novel by David Ebershoff, which now has become a British–American drama directed by Tom Hooper. Screenwriter Lucinda Coxon began working on the screenplay for The Danish Girl in 2004. While she can’t be happy that it took more than a decade for the film to hit the screen, the timing worked out nicely in a purely commercial sense: Thanks to Jenner, transgenderism is now a source of both upscale cultural analysis and lurid popular fascination.

The Danish Girl feels like a worthy art film. The images of 1920s-era Copenhagen—the fish markets, the tiny row homes in primary colours, the high-society fashions—are magnificent. The send-up of the period’s sexology (a pastiche of Freudian constructs and Christian-inspired hysteria over “perversion”) is fascinating. The acting performances from the two protagonists—Eddie Redmayne as Lili and her male antecedent, and Alicia Vikander as suffering wife, Gerda—are technically excellent. And arching over everything is the grand theme of sexual transformation—of a biological man courageously defying a conservative society by following his gendered destiny, at first by mere lace and lipstick, at last by a doctor’s scalpel. It’s the sort of morally uplifting movie that an earnest, liberal-minded couple should be proud to see on date night. Because it’s 2016.

“What’s surprising, even flat-out weird, is how alike all the protagonists are,” writes Plett (who has written often about her own gender transition). “Their lives unfold almost identically: they grow up in unsupportive families; their fathers are domineering or distant; their mothers are kind but frail. When they come of age, they leave humble hometowns to find new lives in the big city. They rent crappy apartments, work menial jobs, detach from their families, and fall in with crowds good and bad. Most of them are physically or sexually brutalized. By the time the novels end, [these] protagonists have fully embraced their true selves… The conclusions are steeped in melancholy hope; in fact, each novel ends with a character gazing, literally or figuratively, into the unknowable distance.”

Much of what Plett writes here applies very much to the plot of The Danish Girl—especially the bit after the semi-colon, albeit with a tragic twist.

To be fair, The Danish Girl does deviate in significant ways from Plett’s stencil of epic gender heroism. In particular, the protagonist here was not some menial worker, but rather a famous artist (born as Einar Wegener) whose life was full of glitter and accolades. He is never shown to be raped; and the one scene of brutality is less shocking than the examples that Plett cites.

Most importantly, Lili’s character deviates from Plett’s observation that popularized trans protagonists “do no wrong; they remain gentle and stoic in the face of difficulty”: Lili sometimes is shown to be unhinged, and can act callously to long-suffering Gerda—especially when Lili refuses to stand by Gerda just at the moment when her own paintings (of Lili, in fact) turn her into an artistic sensation. When an exasperated Gerda declares at one point to her sexually transitioning husband, “It’s not always about you,” she has the audience’s sympathy.

Plett asks: “Why are cisgender [i.e., non-trans] readers so moved by such one-dimensional characters?” At its best, The Danish Girl is not one-dimensional, because it lingers as much on Gerda’s emotional agony and confusion as it does on Lili’s gender. But Plett’s critique feels spot on when she complains that cis-authored novels tend to reduce the complexity of a trans person’s suffering to the subject of gender. To wit: At the beginning of the film, Einar’s whole being is wrapped up in the glorious rhapsody of painting. Yet he abandons his art entirely when he comes out as Lili, who declares herself fulfilled with a job selling perfume at a Danish department store. To any creative person (even, say, a mere magazine writer), this career decision seems completely bizarre. Even if rooted in the facts of Lili’s true personal history, it requires far more explanation than that which the film provides.

When my wife and I got home from The Danish Girl, we started Googling biographical information about the true Lili Elbe. As one might imagine, her life—and in particular, her relationship with Gerda—was more complicated than the film suggests. Of course, true stories always get simplified to some degree in biopics: Every tale needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. But in this case, the variations seemed especially striking. The real Lili, in all her complexity, made me think of Plett’s observation that trans characters created by trans authors tend to dwell on their sexuality as only one part of a (often dysfunctional) self. (By way of example, Plett cites a female post-transition protagonist who “blows her savings on heroin and gets fired for being late to work.”)

In Kim Fu’s 2014 novel about a transgender Chinese–Canadian child, For Today I Am A Boy, a trans woman named Audrey is asked, “What’s your dream? ” She reflects: “If I had other dreams, they stayed hidden behind the bulk of the one dream that consumed all my thoughts, dominated my existence. What else did I want? I couldn’t see past it. I had no energy left for other fantasies.” After describing this scene in her Walrus essay, Plett writes: “It’s hard not to ache for people like Audrey, who face such adversity and fight so hard. I can ache for these characters, too, but only by disconnecting from what I know about transgender life as it is actually lived, and by avoiding the questions that knowledge invites. Questions such as: What if Audrey did have energy for other fantasies? Or what if she transitioned, only to find that it didn’t solve all her problems? The world of the book would open up; the easy, romantic tragedy of it might not remain. I understand why cis people love these characters, but the Gender Novel does not represent the truths of trans lives.”

But hey, I’m cis. What do I know? After quoting Plett at such length, the least I can do is ask her what she thinks about The Danish Girl. Did this film escape the Gender Novel trap—or transcend it?

Casey Plett

I wanted to like The Danish Girl. I didn’t. I would love to see a complex, sad, vivid movie based on Lili Elbe’s life. This movie wasn’t it. I can’t speak for all trans people here, and I know of one trans lady personally who loved this film, but I was bored and frustrated. Here’s why.

So first: Eddie Redmayne. Many people (like me) don’t want to see a cis man play a trans woman again, ever—like, ever. Redmayne is a good actor, and a total babe, and he does perform well here. They still should have had a trans woman play her. Not just for all the usual reasons why cis people playing trans people is dumb; but can you imagine what Candis Cayne, for example, could’ve done with that role? Gerda is kind of fun the first half, though I found her two-dimensional and reductive in the end—starting out as saucy Cool Girl in Act I and becoming Tragic Spurned Wife in Act II.

The script, though. It’s atrocious and boring. It’s like someone got inspired by a Shakespeare tragedy, then combined the verbosity of R.L. Stine with the subtlety of Brendan Fraser. I couldn’t take it. You mentioned the tropes I wrote about in my Walrus article: To me, this exemplified many of those, and more still.

I appreciate (and am flattered by) you holding the film up to my thoughts, but the fact is there are other, older trans tropes besides those contained in the spurt of novels I described. The hysterical/“crazy” transsexual is definitely one of them. And this is the kind of thing that breaks my heart: Most of us know what it’s like to be “unhinged” as you put it, but Lili never moved me on that score. The movie portrayed her as a tragic-mad single-minded hen, not a 3-D complex human struggling with how to manage such impossible levels of pain.

Compare Lili to the two trans protagonists of Tangerine, Sin-Dee and Alexandra. Those two deal with a horde of separate problems, and respond to them in inconsistent ways at different parts of the movie. They’re real, complicated humans. Lili just hits the same woeful note throughout the entire film. I happened to watch both these movies very close to each other, and the humanity given to the trans people involved is worlds apart.

Also, the scene where Lili gets beat up is unnecessary and fabricated—and it pissed me off. There was no purpose to it besides the audience expectation that trans women get beat up just for walking the streets…so let’s beat her up. It is not related to anything that happens before or after in the film. It functions very much like the scenes I described in my article. I couldn’t disagree with you more on this.

I want to be surprised when I watch a trans movie. I want to have my expectations upended. Nothing in The Danish Girl did that. It’s not even like anything in the film gets trans experience glaringly wrong. (The movie is historically inaccurate in various way, but no more so than usual Hollywood treatments.) It’s just that the emotional range is stunted to the point that, as my friend Rani Baker pointed out, the script often reads creepily like forced-femme porn.

I watched the movie with my girlfriend, who is also trans, and she tempered my cynicism as we watched it—observing, “Yeah, I went through stuff like that. I had experiences like that.” With regards to clothes, or the relationship between Lili and Gerta, I had experiences like this, too; this is fair. But as you observed, every character, every scene, every line can be boiled down to, in essence, “Woah, man…gender, right?” The characters never have other motivations or complexities. Even the art bits serve only to highlight impending gender-doom. There are no stakes or tensions in any scene besides that Lili is a girl, and won’t this just ruin it all?

On that note, I think you are unfortunately wrong when you say “The Danish Girl is not one-dimensional, because it lingers as much on Gerda’s emotional agony and confusion as it does on Lili’s gender.” I may not have mentioned it in my Walrus article, but focusing on the poor cis people who must endure a transitioning partner rather than the pain of the actual trans person is also a trope of trans stories. And I’m not too sympathetic to it.

It’s a pretty-looking film, beautifully shot. There are so many gorgeous scenes, whether they contain Lili or no. But to employ a tired trope myself: There’s nothing behind the curtain.

Maybe I’m especially frustrated at the screenwriter because I would’ve loved to write a movie about Lili Elbe, or, at least, I would’ve loved a trans woman like me to write a movie about her. Lili’s life means a lot to me. Man Into Woman had a deep impact on my own life when I read it five years ago.

But, of course, cis people got to make the movie instead. Their film takes zero risks, and yet they will be called brilliant for it anyway. To be blunt, I think you’re more right than you realize when you say: “It’s the sort of morally uplifting movie that an earnest, liberal-minded couple should be proud to see on date night.” I think this movie was made to appeal to people like you, and make you believe you should find it moving and give it awards. To me, it was the kind of safe, syrupy-tragic movie that cis people are supposed to like and feel good about liking. I say: let’s all go watch Tangerine instead.

But since this movie was, in my opinion, made for you and not me, I suppose I could ask: Would you watch The Danish Girl again? Do you think you’d get more out of it each time, the way the best movies stay with you? Did you find it an emotionally compelling and moving film?

Jonathan Kay

I see that we disagree on several important points. Moreover, I think that these points of disagreement get us precisely to the crux of the difference between the way many trans people and many cis people might watch such a film.

To answer your question: Yes, I did think that this was an emotionally compelling film—at least in its early and middle parts. My test for this is whether scenes from the movie forced their way into my conscious mind, unbidden, in the days after I have seen a film. The Danish Girl definitely passes that test.

And the reason for this is that The Danish Girl was written with a cis viewership in mind. Which shouldn’t be surprising, if only from a crass commercial point of view. Cis folk, after all, do constitute the majority of the movie-ticket-buying public. As noted above, I spent a good deal of the film identifying with Gerda, the cis wife trying to figure out what to do with her life in the face of what is (for her) a massive emotional cataclysm. The movie needed a character like that.

You criticize The Danish Girl for “focusing on the poor cis people who must endure a transitioning partner rather than the pain of the actual trans person is also a trope of trans stories.” But why? The most interesting movies (and this applies to all narrative art forms) aren’t “gay movies” or “straight movies” or “trans movies” or “cis movies”—but rather movies about the human condition that happen to focus on gay, straight, trans, or cis characters and themes. Surely it would be limiting, for both artist and viewer, to produce a film that emphasizes only one character’s, or one group’s, perspective. That approach feels like a species of activism, whose influence inevitably has a crushing effect on all forms of art.

Indeed, I would go further than that. For the sake of argument, let us assume The Danish Girl should be judged as a piece of art that is explicitly conceived to show the world only from a trans point of view. Even under this assumption, aren’t the inner lives of cis relatives, lovers, and friends central to the lived experience of a trans person? Transexuality, like all other forms of biologically rooted identity, doesn’t exist in a vacuum: Much of the pleasure and pain a trans person experiences in life will emerge from interactions from cis people. And cis people, like all people, see the world through the lens of their own selfish needs. From Gerda’s point of view, the sight of her (formerly male) husband in woman’s clothing is a sort of emotional apocalypse. All at once, she sees a life unfold before her: spinsterhood, loneliness, childlessness. (This is the world of the 1920s we are talking about, and she is an old maid by the standards of the era.) If Lili loves Gerda, as we are assured she does, then how can none of Gerda’s concerns matter? And if these concerns do matter, how can any filmmaker not deal with them in a serious way?

I will go further: Only by dwelling to some extent on Gerda could the filmmaker even aspire to universalize the film. I remember when Heath Ledger died in 2008, I poured out a column about Brokeback Mountain, in which I finally figured out why the film had such a powerful effects on me. “Brokeback is too often pigeon-holed as a gay love story,” I wrote. “But the homosexuality in the movie was incidental to a larger theme: the random cruelty of the human condition. [Enis and Jack] were gay men living in a homophobic world. When they were true to their love, they lived in a tiny snowglobe of ecstasy. But everywhere else, they were lonely men living a lie. The wreckage in the film is not really about gay love, or even love itself. It is about powerlessness…When Jack famously says to Ennis ‘I wish I knew how to quit you,’ the you could be anything. This is why so many people who aren’t gay, and care nothing for Western vistas and cowboy flicks, were so affected by Brokeback.”

The Danish Girl is no Brokeback Mountain. But at its best moments, it had the same impact on me—an impact that I never would have experienced if there hadn’t been multiple characters I could connect with. And part of that impact, I like to think, is some enhanced understanding of the nature of transexuality, and the history of its persecution in Western society. It is perfectly true that this “was the kind of safe, syrupy-tragic movie that cis people are supposed to like and feel good about liking.” But sometimes you can feel smug, and be educated, at the same time, no?

Casey Plett

You said: “For the sake of argument, let us assume The Danish Girl should be judged as a piece of art that is explicitly conceived to show the world only from a trans point of view. Even under this assumption, aren’t the inner lives of cis relatives, lovers, and friends central to the lived experience of a trans person?”

That feels like a straw man to me? Of course they’re central. That’s a false choice. If you have taken in pieces of more trans-centric art, you would likely know it is certainly possible to house both phenomena (a trans POV and an empathetically portrayed cis character) under the roof of one work.

Look at Steph in the novel Nevada, for instance, the cis ex-girlfriend of the book’s protagonist, Maria. Both cis and trans readers can relate to Steph; her viewpoint in the book is super crucial to understanding the main characters, and furthermore Maria is a jerk to Steph in many ways that have little to do with her transition per se. Yet few works are more explicitly for a trans audience than that book. Razmik in Tangerine is a very real and sympathetic character. The short film Roxanne, about a trans sex worker and a cis child on the streets, is shown quite evocatively through both characters’ eyes. The upcoming show Her Story appears in previews to centre trans women while containing interesting and developed cis characters.

If you are familiar with works like this, then that’s another conversation, but I think if you were more acquainted with different types of trans art, you would see a difference between these works and The Danish Girl.

Furthermore, I think you are making a very crucial miscalculation here—that because I am saying a trans movie made for cis people won’t speak to trans people, that therefore the converse is true: A movie explicitly conceived with a trans audience couldn’t interest cis people, and therefore no one would buy tickets. I’m sorry if I’m putting words in your mouth here, I don’t mean to, it’s just that this is a common misconception and it’s so incorrect. Non-Mennonites enjoy Miriam Toews’s books, folks who’ve never been prostitutes are moved by John Rechy and Amber Dawn, and non-indigenous Canadians can and should read Leanne Simpson. I would argue (to the degree I can do so without asking them) all these authors speak to their own communities first, and by doing so end up with better books that, it turns out, everyone can appreciate.

You suggest that my approach “feels like a species of activism whose influence inevitably has a crushing effect on all forms of art.” I get it, it feels like part of my argument, centring the viewpoint of a small group of people, rubs up against ideals of making art for a universal humanity, that feels like the narrow-minded propaganda books of The Jungle or Horatio Alger books or something. I feel like that’s the argument you’re getting at. But I would suggest that my approach, not worrying about educating outsiders, not compromising work in order to be accessible to folks in the majority, that actually allows artists a freedom to speak the truth as they see it, intimately and without fear.

I would posit this is actually a very good way to come up with great art.

To limit trans art to a cis viewpoint in the hopes of education, that is a species of activism, that has a crushing effect on art. You mention being “educated” as a pro to this movie (an argument I also refuted in my Walrus article), and by that token I’d ask: What could be more intimate, revealing, what could an outsider learn more from, than listening in via novel or film an artist speaking to their own community?

And if trans people made a good movie with a trans audience in mind, don’t you think you would be interested in seeing it and probably like it?

I refer you back to Nevada once again. That book will tell you more about trans women than The Danish Girl ever will, and cis people love it too, because it’s just a damn well-written book. Zoe Whittall writes for queer people; tons of straight people love her books because they’re fantastic by any standard. (And can you not learn loads about the Referendum-era Montreal queer scene by reading Bottle Rocket Hearts?)

You say, “Surely it would be limiting, for both artist and viewer, to produce a film that emphasizes only one character’s, or one group’s, perspective.” But every piece of art has a perspective in mind and choices to make about audience. It is impossible not to limit perspective to various characters and groups. We’re doing that right now as we go back and forth, making assumptions of which references and terms our readers will get and which ones we will need to explain, and, likely, choosing such references and terms accordingly. (I am already fretting that the reference of The Jungle will not land to a Canadian audience, as this is an American book frequently taught in US high schools like the one I attended, yet I have no Canadian example that works remotely as well, so this is a choice I make and here we are.)

Every piece of art makes those choices. Some get more leeway with those choices then others. Cis people have generally been allowed to make stilted and inaccurate art about trans people without anyone questioning them. Now that’s changing, hence why we’re having this discussion at all.

If we lived in a world where trans people made art about trans people with the freedom, access, and resources that cis people make art about trans people, I wouldn’t be so bothered. But we don’t. So I am.

Finally, like I said before, I’m glad you asked me to contribute my perspective (I would like to request every cis reviewer to likewise consider calling their resident transsexual before pontificating solo on these works). I would also respectfully wonder how your missives on this subject might change if you had to compare The Danish Girl to work by actual trans artists. And finally, if you’re interested in learning more about Lili Elbe, scout a copy of Man Into Woman. Unlike the movie, it contains words written by her.