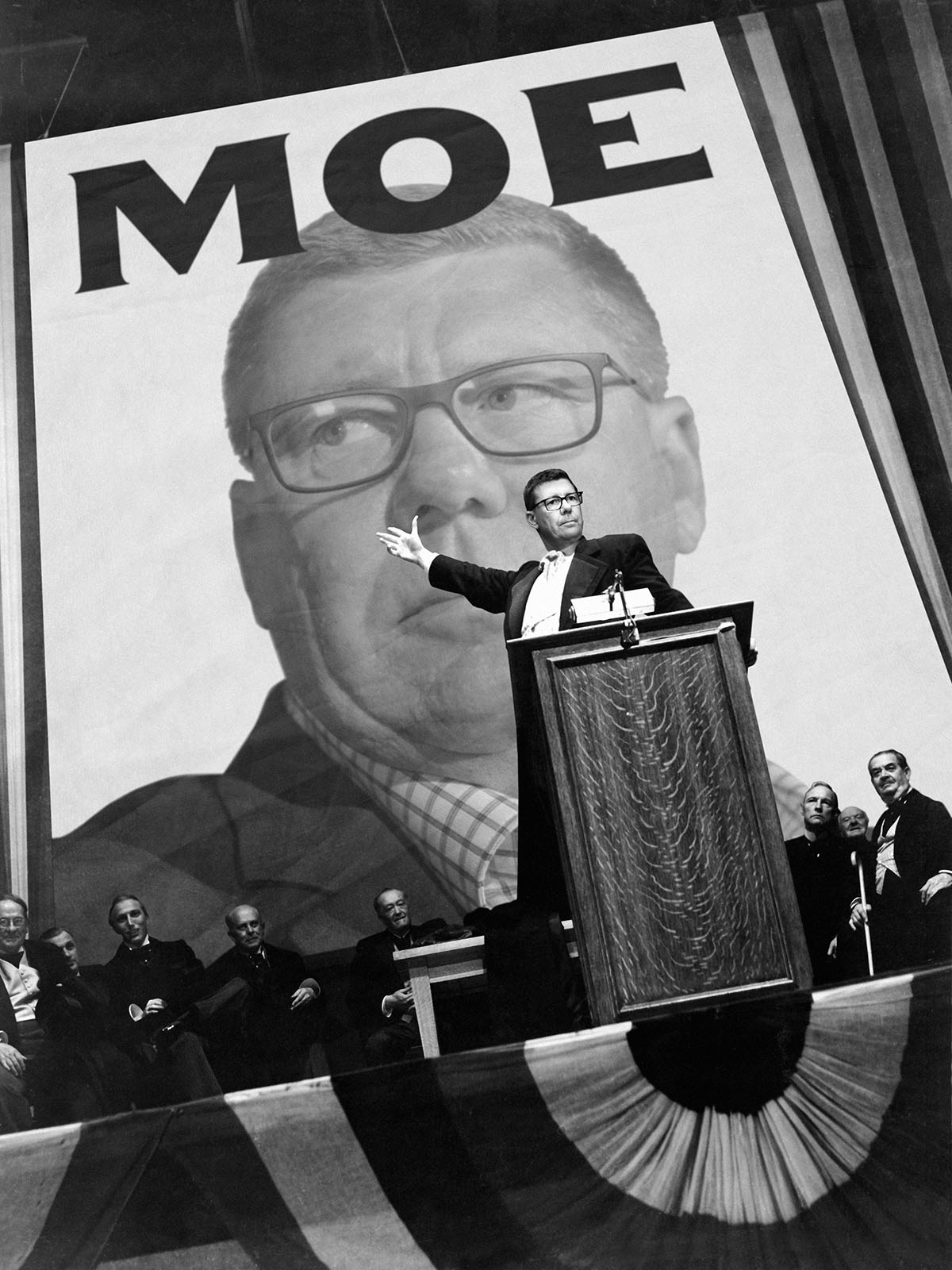

One evening in January 2018, Scott Moe, a former Saskatchewan environment minister, won the leadership of the Saskatchewan Party and became premier designate of the province. Before a room of buoyant supporters in Saskatoon, and between fist bumps with his family, he casually declared, “We will not impose a carbon tax on the good people of this province . . . and Justin Trudeau, if you are wondering how far I will go—just watch me.” The phrase was a play on former prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s response during the 1970 October Crisis when a CBC reporter asked how far he would go to maintain order and if he would suspend civil liberties in Quebec. (Days later, Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act.)

But even people in that room had raised their eyebrows at Moe’s ascent in the party—including Moe himself, who, in one of his first public appearances post the election, described a text he had received from his brother-in-law: “‘Scott, are you the premier of Saskatchewan? WTF?’” Moe had been the second, even third, choice—the “least disliked” contender, John Gormley, a former member of Parliament and former radio host, once said. People were unsure how Moe, described by friends as ordinary and normal, would fare in his succession of the charismatic former party leader and premier Brad Wall. A successful salesman and communicator, Wall had helped bridge the province’s long-standing rural–urban divide and appealed to a more moderate pool of voters.

For many Canadians, Saskatchewan—a province of over a million people in a space roughly the size of Texas—is something of an afterthought, a land of rolling prairies and infinite blue skies. But for those paying attention, Moe has become the face of a province that may have considerable sway over the nation’s climate policies and the heart of an increasingly Donald Trump-esque ideology. A man of nebulous personality, which shape-shifts as per the moment’s needs, Moe has established himself as one of the most popular premiers in the country. March data from the nonprofit Angus Reid Institute indicated that Moe had a 53 percent approval rating—one of only two provincial leaders in the country to exceed the majority mark that quarter.

The “watch me” moment has since become a defining aspect of Moe’s six years as premier—and, with it, his adversarial relationship with Prime Minister Trudeau’s federal Liberal government. As Simon Enoch, director of the Saskatchewan office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, explains, this confrontational stance is Moe’s “one-trick pony,” which “seems to work.” Moe has successfully inched Saskatchewan politics further right—with extreme climate, LGBTQ2S+, education, and economic policies. The party has expanded the range of policy possibilities that the public is willing to accept. “You see consistently, over the past two or three years, a movement towards being a solid right-wing populist party, led by a right-wing populist guy in the form of Mr. Scott Moe,” says Ian Hanna, former special communications adviser for Wall. “There’s a transition in the party and a transition in the province.”

The Saskatchewan Party’s perennial challenge has been to appeal to urban voters, who tend to lean more to the centre or left. But Moe’s drastically loose COVID-19 policies and willingness to touch hot-button issues around gender and the environment have isolated him further from more swing and moderate voters. He can be impetuous in press conferences and the legislature and, to many residents, has become increasingly reckless, even dangerous, in his policy decisions. (Emails to Moe’s communications staff requesting an interview went unanswered.)

In October, Saskatchewan will hold its general election and vote for members of the legislative assembly. In May, though, a series of scandals led to then speaker Randy Weekes taking to social media with a photo of his Saskatchewan Party membership card cut in half, with the caption “Enough is Enough.” Six cabinet ministers have also decided not to seek re-election. All told, eighteen of Moe’s forty-six MLAs who were in caucus last fall are not running again.

Still, “he’s going to win the next election,” Hanna says. The Saskatchewan electoral system is configured so Moe can lose almost every urban vote in the province and maintain his leadership in the general election. The question many around the country are left asking is: What makes him so popular?

Moe, born in 1973 in Prince Albert, the province’s third largest city, on the banks of the Saskatchewan River, personifies rural Saskatchewan. The eldest of five siblings, he was raised on a farm in a predominantly white community of 1,400 called Shellbrook, just west of Prince Albert. He attended the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon, obtaining a bachelor of science in agriculture. He fishes, snowmobiles, and golfs. In the mid-’90s, he and his wife started a farming business, which later went bankrupt. He also owned a gas station and a pharmacy.

Saskatchewan’s rural residents comprise over a third of the province’s population, according to a 2021 report from the Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation. Many of the province’s residents are farmers, or only one or two generations from having lived on a farm. Its agricultural land comprises some 40 percent of Canadian farmland, earning the province its moniker, “the bread basket of Canada.” Saskatchewan is also rich in natural resources: it is one of the world’s largest producers of potash and uranium, and oil and natural gas, found beneath the prairie, are among its most valuable resources.

Because rural and small communities represent a solid portion of the voting population, much of Saskatchewan politics has catered to a stark rural–urban split. Before the 1980s, the province had been governed largely by the New Democratic Party and the social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation that co-founded the party. In 1982, to the shock of many, the province voted in Grant Devine, who led a Progressive Conservative government and transformed Saskatchewan politics, turning the once-powerful NDP into a shell of itself. Murray Mandryk, a local political columnist, told the CBC that Devine ran the worst government in Saskatchewan’s history, leaving taxpayers with more than $10 billion in debt.

In 1991, the Devine government was dissolved, in one of the biggest political corruption scandals in Canadian history, leading to the criminal convictions of sixteen MLAs or staff on charges of fraud and breach of trust. One of Devine’s ministers, Colin Thatcher, was convicted of killing his estranged wife; others were implicated in the infamous caucus fraud scandal—a scheme involving cabinet ministers and staff siphoning off over $800,000 of caucus communication money. One MLA spent that money on a Hawaiian vacation, while another used it to purchase a saddle and bridle sash engraved with his name. Tragically, one cabinet member took his own life.

The Devine era “is legend and lore around here,” says Tammy Robert, a communications consultant involved in Saskatchewan politics for two decades. The epoch came to signify excess, self-aggrandizement, and corruption, leaving the right fractured. The Liberal Party and Progressive Conservatives fought over the right-wing vote, which made it easy for the NDP to sweep in and win multiple elections in the ’90s. To control the Devine government’s debt, the NDP, led by Roy Romanow, restructured health care and closed or converted hospitals in rural communities, leading to a wide sense of betrayal and animosity. (In 1960, then Saskatchewan premier Tommy Douglas, a socialist, had introduced a universal insurance plan in the province, a first for the country. Within the next decade, government-sponsored health insurance covered the rest of Canada.)

“Put simply, Scott Moe has learned how to speak to the worst among us.”

To oppose the NDP, the right needed to unite. In 1997, an amalgam of Liberal Party members and former “completely demoralized and ethically besmirched Conservative Party members,” as Hanna puts it, founded the Saskatchewan Party. By exploiting rural grievances—disappearing social services, lack of employment opportunities, and the demand to protect oil and gas—the party was almost immediately successful in garnering the rural vote but struggled to appeal to city residents. In 2004, Brad Wall, a former ministerial assistant in the Devine government, became its leader. Wall led a policy review of the party’s failure to make inroads with female and urban voters and departed from some of its more controversial policies like opposing abortion and sending young offenders to boot camps.

“We pulled it off,” Hanna says of the party’s successful takeover in 2007 under Wall, “because there’s this big, lazy middle of disengaged people who . . . spend their lives not even thinking about what’s going on with the legislature.” He says there were hard-core voters on either side of the spectrum who always voted conservative or always voted NDP no matter what. The Saskatchewan Party, however, “captured the centre.” Moe, who had been living in Alberta selling farm equipment until he returned to Saskatchewan in 2003, was elected as a Saskatchewan Party member of the legislative assembly in 2011. He quietly rose through the ranks, serving in the cabinet from 2014 to 2017, under Wall, as minister of advanced education and twice as minister of environment.

In 2017, when Moe announced his candidacy for the party leadership from a trucking yard in Saskatoon, he had the endorsement of several prominent caucus members. The following year, he beat out three provincial cabinet ministers and a senior civil servant. When he became premier, according to sources, Moe was the party’s puppet, riding the strong brand Wall had built. But that quickly evolved. Moe “articulates a strong anti–federal government bias, a strong liberal bias, and stirred into all that is a virulent anti-union bias, which resonates with his supporters,” Hanna says. Robert agrees and says the Saskatchewan Party appeals “to that right-wing victim movement in Saskatchewan and Alberta” that was central to the convoy—referring to the 2022 trucker movement that converged in Ottawa and called for an end to COVID-19 vaccine mandates. “Put simply, Scott Moe has learned how to speak to the worst among us,” Robert says, “the people who are already angry.”

In 2017, when Moe began his leadership campaign, some of his personal skeletons tumbled out as he released a statement about his driving record. Moe had been convicted of drunk driving in 1992, when he was eighteen; in 1997, at twenty-three, he had collided with another car, killing the driver (the woman’s then teenage son survived). Moe received a ticket for driving without due care and attention, a provincial traffic violation. The news caused a minor scandal but not enough to hamper his win.

During his 2020 campaign, more of Moe’s past became public. He had faced charges in 1994 on two counts: impaired driving and leaving the scene of the accident (both charges were later dropped). A man named Steve Balog, whose mother, Joanne, was the victim of the 1997 fatal car crash, came forward publicly to disclose that Moe, previously unknown to him as the driver of the vehicle, had never personally apologized. (Balog and Moe later met, and Moe reportedly apologized.) That July, Moe disclosed the names of several Saskatchewan Party candidates convicted of impaired driving, revealing that nearly 10 percent of party candidates had such convictions.

The party has also been accused of exploiting the province’s inadequate laws around conflict of interest and campaign finance. The party has accepted millions of dollars in out-of-province corporate donations, and current rules allow foreign-owned companies based in Canada to pay for political influence in Saskatchewan. “Saskatchewan is the Wild West when it comes to campaign finance laws,” Duncan Kinney, executive director of the Edmonton-based Progress Alberta, told the CBC in 2016, after finding that out-of-province contributions from oil and gas, banks, and construction companies were flowing into the Saskatchewan Party. Responding to criticism, Wall had said the system was “robust.”

Robert believes private special interest groups unduly influence public policy. “Unelected citizens are running the government through puppet MLAs who are more than willing because they then go on to profit,” Robert says. Saskatchewan’s permissive conflict-of-interest laws allow MLAs and premiers, once out of office, to quickly become government lobbyists or to take up lucrative board appointments. Earlier this year, the NDP accused two Saskatchewan Party politicians of using government contracts to “cash in” for private interests. In June, Wall was inducted into Saskatchewan’s Oil and Gas Hall of Fame.

More recently, former speaker Randy Weekes accused Jeremy Harrison, one of Moe’s cabinet members, of intimidating behaviour and almost causing a security alert at the legislature in 2016. Harrison had walked into the building in camouflage gear, carrying a long gun in a case. It happened around a year and a half after a lone gunman killed a ceremonial guard at the National War Memorial in Ottawa and was shot to death entering Parliament. Later, Harrison admitted to the incident and said it was a mistake; he resigned as government house leader but remained minister of trade and export development as well as of immigration and career training.

While Moe remained the loud, boisterous voice behind the scenes, several MLAs like Harrison, who have been a constant through the Wall and Devine governments, pulled the strings. “Unlike Moe,” says a former Saskatchewan politician who requested anonymity, “they are the political Machiavellian operators, and they don’t fuck around.”

As soon as Moe entered office, he began calling for sweeping policy changes. The moderate facade Wall had built for the party began to dissolve as Moe tried to appeal to a more right-leaning base of supporters. One of his primary focuses was defending and bolstering the province’s recently crashed oil and gas industry.

Saskatchewan is a resource-based economy and the second largest oil-producing province in the country, after Alberta. While commercial oil production began to flourish in the 1950s, the province has advanced technologically to increase the pace and scale of drilling. In the mid-2000s, Saskatchewan experienced an oil boom, which coincided with the province’s broader economic prosperity, dubbed “Saskaboom.” For nearly a decade, Saskatchewan saw social services, employment, and economic opportunities—as well as emissions—soar. In 2014, however, oil prices dropped globally, and the industry took a hit. Rural communities questioned their future livelihoods, and Moe took it on as his mission to combat what the party saw as overly encroaching and ambitious federal climate policies. “If you want to understand why robust national climate policy is being blocked,” says Simon Enoch of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, “look to Saskatchewan.”

The province’s emissions, mainly from oil and gas, are the highest per capita in Canada, nearly 250 percent higher than the national average. The province also has among the highest per capita greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. In 2016, under the Paris Agreement, Trudeau committed Canada to emissions reductions to 30 percent below 2005 levels. Wall rejected the federal approach, and Saskatchewan is the only province that hasn’t signed the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, a countrywide plan to address climate change. The Saskatchewan Party introduced Prairie Resilience, a “made-in-Saskatchewan” climate strategy that includes best-performance standards but no carbon price.

In 2018, Parliament passed the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, a federal law establishing a minimum national standard for carbon pricing to meet Paris Agreement targets. The legislation is meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, creating a financial incentive for people and businesses to pollute less. The federal strategy allows provinces or territories to design their own pricing systems as long as they meet basic standards. Moe took the federal law to provincial court, challenging its constitutionality. The provincial court of appeal sided with the federal government. Along with Alberta and Ontario, Saskatchewan then took the carbon tax to the Supreme Court, again challenging its constitutionality, claiming it was “ineffective” and “job-killing.” The court, in a 6–3 decision in March 2021, upheld the lower court’s decision.

In 2022, at a Prince Albert and District Chamber of Commerce event, Moe was asked about Saskatchewan’s environmental record. “A lot of folks will come to me and say, ‘Hey, you guys have the highest carbon emissions per capita.’ I don’t care,” Moe said. “We have the highest exports per capita in Canada as well. We make the cleanest products, and then we send it to over 150 countries around the world.” Earlier this year, the Saskatchewan Party government decided not to remit the federal carbon tax on natural gas, violating federal law. Moe later announced that the Canada Revenue Agency has plans to audit the province. Trudeau said the agency is “very, very good” at getting money owed and wished Moe “good luck.”

Moe has found a unique ability to exploit fears that afflict more insulated Saskatchewan residents and aggravate long-standing racial tensions. In 2016, five Indigenous youth, including twenty-two-year-old Colten Boushie, from Red Pheasant Cree Nation, had spent the day drinking and swimming in a river when they had car trouble and drove onto the property of a fifty-four-year-old white farmer named Gerald Stanley. Stanley fatally shot Boushie in the back of the head. During the ensuing trial, Stanley’s testimony raised issues about trespassing and rural crime as central to his defence that his gun had gone off accidentally. In 2018, Stanley was acquitted of second-degree murder.

The case fed perceptions that theft and property damage in rural communities have become ubiquitous and that Indigenous people are to blame. Some fifteen years ago, in response to concerns among farm and rural property owners, Saskatchewan had passed the Trespass to Property Act, which made it a ticketable offence to be on someone’s property if they object. A few months after the Stanley verdict, the province reviewed those laws while the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities pushed for changes and Farmers with Firearms advocated for the armed defence of rural property. In 2021, Saskatchewan amended its trespassing laws, allowing landowners to take civil legal action against trespassers and increasing fines to up to $25,000 in certain cases.

In particular, these changes affected Indigenous people, who have inherent and treaty rights to hunt, fish, gather, and access traditional lands. According to Michelle Brass, a member of the Yellow Quill First Nation, the amendments have made Indigenous people feel unsafe while exercising these rights. Apart from public property, the only land that Indigenous people can freely access is Crown land—including reserves. This land is increasingly being sold off or leased, in what Trevor Herriot, a prairie naturalist and writer, says is a “hidden tragedy” that can threaten the region’s biodiversity. First Nations communities have accused the provincial government of privatizing land within their traditional territories without their knowledge. In response to the Boushie tragedy and the amended trespassing laws, the Treaty Land Sharing Network was created, a group connecting farmers with First Nations and Métis people to provide safe access to land.

Brass says the amended trespassing laws exacerbated pre-existing racial tensions following the Stanley verdict, feeding “the divide that had gripped Saskatchewan at that time.” The trespassing laws were designed to appeal to a particular base of Moe’s supporters, she says, “to create a sense of safety and that something was being done about the ‘problem.’” In effect, Brass says, this reduced the issue to one of “crime and trespassing,” which was “grossly negligent” and “contributed to the racial tension in this province.”

Two years later, Moe took on another contentious issue: gender identity. In August 2023, ahead of the school year, the government posted a news release online stating that school divisions must seek parental consent when students under sixteen want to change their name or pronouns used at school. Similar “parental rights” movements—often involving anti-government and right-wing extremist groups advocating against schools teaching about issues relating to gender, sexuality, and race without parental consent—have spread across the US and several provinces in Canada, including New Brunswick and Alberta.

Lawyers with the UR Pride Centre for Sexuality and Gender Diversity and Egale Canada, an LGBTQ+ rights organization, filed an injunction, which was granted that September. Moe characterized the injunction as “judicial overreach.” That October, he called an emergency session in the legislature and invoked the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The clause prevents a court from invalidating a law that violates Charter provisions on fundamental freedoms and legal and equality rights. The legislature passed Bill 137, the Parents’ Bill of Rights. (A poll released in December 2023 by the Angus Reid Institute found that most Saskatchewan residents support the bill.)

Bennett Jensen, legal director at Egale Canada and co-counsel for UR Pride, said the bill has had a chilling effect across schools in Canada, causing grave harm to youth who are being misgendered. “Teachers are scared to talk about the fact that gay people or trans people exist,” Jensen says. “Political leaders are talking about how mentioning the existence of gay or queer or trans people is sexualizing children. The stigmatization that is happening at this moment can’t be overstated.” For some youth, “this is truly life or death, and I don’t use that lightly.”

Moe may have begun as a compromise, a “shapeless” premier, someone opposition figures mocked in the legislature, shouting “We want Moe” or “Four Moe years.” And whose opposition to the federal government, to the chagrin of many, led him to claim Saskatchewan should be a “nation within a nation.” And whose influence is often overlooked. “He’s a potato,” says the former Saskatchewan politician quoted earlier, “and potatoes may not be the most appealing part of the meal, but they’re fine on the side of the plate; they don’t bother anyone.”

This facade almost works in his favour as the party works behind closed doors to shape policy that could threaten Canada’s future. But it would be a mistake to overlook Moe’s place as the standard bearer for an extremely popular party and a conservative province whose grounds are fertile for populism. For many, Moe appeals to people’s worst instincts in an increasingly polarized province—and country. “You’ve got this entitled white guy who has failed upwards his entire life running the province and is now at the pinnacle of his power in that role,” Robert says. “He has become more dangerous and more reckless because of this.”