“Ralphie at the races” is a story by Samuel Selvon that, like much of his short fiction, is structured as a joke. Set in Calgary, the immigrant tale follows a freshly arrived Trinidadian whose friend drags him to Stampede Park to watch the horse races. Ralphie refuses to bet, but he keeps picking the right horses and collapses into “utter despair” at the thought of the money he passed up. Finally, he bets on the last race and wins again, but in the ensuing excitement, he loses his ticket.

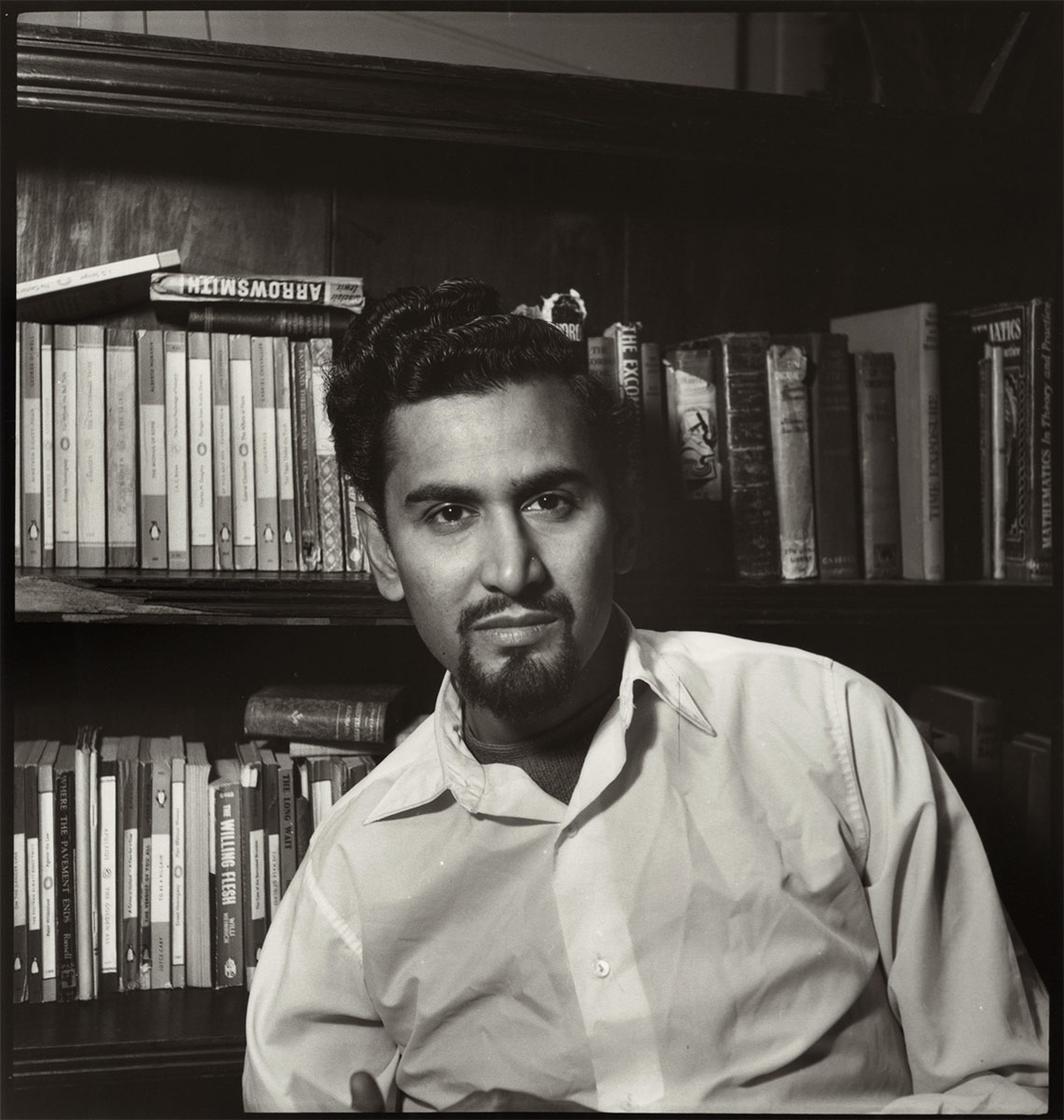

When Selvon himself immigrated to Calgary, in 1978, he was an accomplished writer with nine novels to his name. He leapt onto the scene in England with fiction that turned colonial subjects into protagonists, whether they be cane cutters in rural Trinidad or minorities in London hustling for jobs and women. His best-known work, 1956’s The Lonely Londoners, depicts the tragicomic struggles of working-class Caribbean men through an innovative use of creolized English and thrilling stream of consciousness. One largely unpunctuated, ten-page ode to urban promiscuity begins, “Oh what a time it is when summer come to the city and all them girls throw away heavy winter coat and wearing light summer frocks so you could see the legs and shapes that was hiding away from the cold blasts and you could coast a lime in the park.” These days, several of Selvon’s novels bear the imprint of Penguin Modern Classics. His good looks are on display in the National Portrait Gallery, right off Trafalgar Square, where his photograph appears next to Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing.

But when Selvon arrived in the Canadian west, he seemed very much a man who had lost his winning ticket. None of his accomplishments seemed to matter. He struggled with underemployment in the initial years, landing one visiting position at the University of Victoria but unable to find anything more stable. “I can’t even buy a mouth-organ for my son for Christmas, nor boil a ham, things so expensive,” he wrote in a December 1980 letter. Eventually, the University of Calgary hired him—as a midnight-shift janitor. He spent only a few months as caretaker before the English department wised up and gave him a writer-in-residence position. Still, his years in Calgary, which stretched from 1978 to his death in 1994, remain an aporia within Canadian literary history. Selvon has never been fully integrated into our curricula or canon, and the Canadian editions of his novels received few reviews.

According to the late Barbados-born and Toronto-based novelist Austin Clarke, this critical neglect was a travesty that demonstrated the worst elements of the Canadian literary establishment. As Clarke complained to Selvon in a 1980 letter, “You have to be born here, preferably on a farm, and you have to write about growing up with cow-dung betwixt your toes, in order to be taken seriously by those people who think they know about writing and literature.” The year of Selvon’s death, Clarke dedicated a full book to their friendship, A Passage Back Home. In it, he blames Selvon’s frosty reception on “the parochial disposition of the Canadian, and in particular the Western Canadians, towards literary interlopers.”

One can hope that times have changed for immigrant writers; Clarke himself won the Giller Prize in 2002 for The Polished Hoe. Yet, thirty years after his death, Selvon is still on the margins here. Is his story yet another tragedy, the writerly version of the immigrant whose credentials are never recognized? How can we make sense of the internationally feted giant of Caribbean literature who wound up among hay bales and cowboys?

In one sense, Selvon’s ties to Canada go back to his youth. Born in 1923 in San Fernando, he was educated at Naparima College, a secondary school established by Canadian missionaries who sought to convert Trinidad’s Indian community to Presbyterianism. But his first migration, in 1950, was more predictable: in his late twenties, after working as a journalist with the Trinidad Guardian, he boarded a ship to London, the imperial metropole. Selvon thus joined the so-called Windrush Generation, roughly 300,000 people from the Caribbean who moved to the United Kingdom between the late 1940s and early 1970s to secure employment and help rebuild a war-battered country. Famously, he was on the same ship as Barbadian author George Lamming, who commemorated their crossing in his 1960 book of essays, The Pleasures of Exile. Both planned to be writers, and the “secret society” that they formed on the boat prefigured a broader shift: the birth of a regional identity. Lamming was of African descent, Selvon Indian, and each came from a different island, but in England, their similarities became clear.

This new concentration of Caribbean writers in and around London drove an explosion of literary activity, with Selvon as a central figure. He participated regularly in the BBC program Caribbean Voices. His first novel, 1952’s A Brighter Sun, attracted praise for detailing the lives of Indo-Trinidadian peasants as they balanced tradition with the pursuit of education. It has since become a fixture of high school curricula across the Caribbean. An Island Is a World (1955), a middle-class bildungsroman, was less successful but outlined his commitment to creolization, whereby a Trinidadian identity trumps internal ethnic divisions. With The Lonely Londoners, Selvon crossed the racial divide himself by focusing on characters of African descent. The hit has helped earn him the title of the “father of black writing” in Britain, with descendants like Zadie Smith.

Selvon’s second move, some three decades later, was symptomatic of the gap between cultural capital and cold hard cash. In expensive London, even a successful author’s earnings were insufficient. “I could never write fast enough to keep up with basic expenses like rent and food,” he later observed. He kept publishing novels through the late 1950s and into the early 1980s, including sequels to A Brighter Sun and The Lonely Londoners. He also received a visiting post in Scotland, at the University of Dundee, from 1975 to 1977. But as the English economy eroded and local critics seemed to move on from Caribbean literature, many of Selvon’s peers decided to cash in on their reputations elsewhere. Some returned to their home region to teach at the University of the West Indies, while others became professors at major institutions in the United States.

That Selvon chose Calgary was contingent. “That was where my wife wanted to go,” he wrote in a journal article in 1987. “She had visited relatives (who had immigrated there) a few times and glowed as she compared the standards of living.” In 1978, Alberta was riding an oil boom, and Calgary was attracting droves of interprovincial migrants. The prairie city of around 500,000 people was also a far cry from cosmopolitan London. In moving there without a job lined up, perhaps Selvon was betting his reputation would follow him.

“It’s hard to say exactly how he would have described his initial years in Canada,” Kris Singh tells me. The English instructor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University is part of a cluster of Canadian scholars re-evaluating Selvon’s legacy. In May 2023, he participated in a special panel at the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, the country’s largest academic gathering, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Selvon’s birth. Also on the panel was Cornel Bogle, an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University.

Singh and Bogle have pored over Selvon’s correspondence with Clarke, archived at McMaster University, to examine how diasporic writers support one another. Outside of Canada, Clarke was the lesser-known figure, but he had been based in the country since 1955, and Selvon turned to him for advice and contacts. The letters themselves are riotous documents: the two constantly trade jabs, with Selvon signing off one letter by telling Clarke, “God will bless you, son, don’t mind you black. And ugly.” Singh and Bogle read such moments as banter that satirizes racial divisions and affirms their intimacy. “There’s so much care hiding behind these postures of masculinity,” Bogle explains. The humour also makes Selvon’s situation harder to parse. Confessing to despair was not his style.

Neither scholar can offer a simple explanation for the Canadian neglect of Selvon’s work. Bogle observes that his residence on the prairies, far from the emerging Caribbean networks in Montreal and Toronto, made him an “oddity.” His status as Indo-Trinidadian may also have worked against him, given the academic tendency to focus on Black writers. Karina Vernon’s landmark 2020 anthology, The Black Prairie Archives, which seeks to disrupt the region’s realist and white literary tradition, thus makes no mention of him.

Another complicating factor was Selvon’s own silence. During his sixteen years in Alberta, he published little. His tenth novel, Moses Migrating, appeared in London in 1983; its humorous plot follows the protagonist of The Lonely Londoners on a return voyage to Trinidad, where he sleeps around and earns a prize for a carnival costume that satirizes the British empire. Other new material from this period is rare, and “Ralphie at the Races” may be his only published work set in Canada. As Singh tells me, while “we can speculate about how Selvon’s Canadian isolation affected his relationship-building and writing,” we can’t truly know why his creative well ran dry.

The image of the unrecognized author stranded on the prairies, who struggled to write in the absence of community, is a strong one. Yet people who knew Selvon during his time in Calgary offer a competing narrative: he was a humble and good-natured man with nothing left to prove.

Originally from Trinidad, Ruby Ramraj moved from New Brunswick to Calgary in 1970 so that her husband, Victor, could take up a position in the University of Calgary’s English department. He was a specialist in postcolonial literature who knew Selvon long before his arrival. Victor passed away in 2014, but Ruby and I spoke on the phone. After the Selvons relocated, “we became family friends,” she explains. As she recalls, Selvon and his wife, Althea, came to Calgary for pragmatic reasons: the city seemed like a good bet for the family, with educational opportunities for their children. Then there was the matter of property. According to Ruby, Althea’s brother had pointed out that “if they came here, they could actually buy a house, a whole house to live in.” They eventually secured that house, in the neighbourhood of Charleswood near the University of Calgary, where Althea landed an administrative position.

In those early years, Ramraj’s husband worked to put Selvon’s books on the shelves and convince his colleagues of the author’s stature—“the university wasn’t really aware of Sam Selvon and how important a writer he was until a lot later in his tenure in Calgary.” Yet her memories of Selvon’s time as a janitor are not exactly tragic. The position was well compensated, and Selvon himself did not seem especially put out. “He said, look, I’m already a writer. I can do anything.” Back in 1985, in a Calgary Herald Sunday Magazine feature that highlighted Selvon’s transition from cleaning staff to writer-in-residence, he said much the same. “It didn’t bother me to work as a janitor for a few months, you know. . . . In fact, I rather enjoyed it.”

After about four years, Selvon’s professional situation improved. In addition to his work at the University of Calgary, he took visiting positions at other institutions in Western Canada. He became a regular on the conference circuit and received Canada Council for the Arts grants, which he used to fund writer’s tours and research travel back to Trinidad. During this period, his reputation in the UK and his homeland continued to grow. He received honorary doctorates from the University of the West Indies in 1985 and the University of Warwick in 1989. His public persona remained decidedly unpretentious. He’d never attended university himself, and in a 1992 interview, he described himself as a “primitive writer” who followed his instincts and “paid very little respect to the rules, purely because I’m ignorant of them.”

Selvon’s youngest daughter, Debra, does not remember much about the move, as she was only five at the time. Above all, she recalls her brother suggesting she say “I am a Canadian” with a twang in order to shake her English accent. In those early years, she thinks, her older brothers had a harder time adjusting, and her father once told her mother “he’d dig graves if he had to, to assist in the bills.” But she likewise remembers her father having few close friends, including writers and professors. He was quite pleased with his honorary degrees. “I overheard him speaking to his friend on the phone and asking him to refer to him as ‘Doctor Doctor,’” she wrote to me.

As for recognition by the Canadian literary establishment, she’s not sure he cared. After all, “Trinidad and England gave him so much.” Ramraj agrees. “I think he was good in his own skin and he knew what he did.” Selvon became a Canadian citizen in 1981, and in interviews, he described the country as easier to adjust to than England. Yet, as he flew off for frequent international speaking engagements, he may have had little reason to envy fellow Calgarians crossing their fingers for prizes from Ottawa.

Selvon also remained deeply attached to Trinidad. “I have never thought of myself as an ‘exile,’” he wrote in 1987. “I carried my little island with me, and far from assimilating another culture or manner I delved deeper into an understanding of my roots and myself.” His last days have been mythologized as a result. In 1994, he fell ill during a trip to the island and developed pneumonia. He died on the tarmac at Piarco International Airport, en route to the jet ambulance that was supposed to fly him back to Canada.

For some, these final moments symbolize the country taking back its native son. One of his novels is called Those Who Eat the Cascadura. According to local legend, anyone who samples this island fish will end their days in Trinidad. In a commemorative tribute to the writer, Trinidadian author and educator Ismith Khan returns to this tale to frame Selvon’s passing as a poetic form of fate. “I am glad Sam returned to Trinidad, it would have been too lonely to be buried in England or Canada, both of which are far too cold for someone who loved the sun, loved his island, and loved his people.”

Back in calgary there was a memorial service for Selvon. ARIEL, a quarterly literary journal, published a special edition on his work. They included an excerpt from an unfinished novel, tentatively titled A High of Zero, that was set to take place in Trinidad, England, and Canada. It’s easy to fantasize that this book, which added up to about 130 handwritten pages, would have provided the missing link, the local triumph that would have staked his claim as a Canadian author. Clarke, of course, insisted that the criteria for belonging—“cow-dung betwixt your toes”—were narrower than that.

The paradox, though, is that the Canadian literary establishment was never powerful enough to doom Selvon to obscurity. His place in literary history was already assured elsewhere. In the end, the struggles of his early years in Canada combine with more benign images: Selvon the writer who collected his honorary doctorates and mingled with authors and professors, Selvon the homeowner who played Scrabble and grilled salmon with the Ramraj family, Selvon the gambler who loved to watch the horse races at Stampede Park. If his reputation never fully transferred over to Canada, that was a bet the doctor doctor could afford to lose.