The ivy-covered brick house Michael Snow shares with his wife of twenty-eight years, the writer and curator Peggy Gale, is a far cry from the bohemian Manhattan loft where he spent much of the ’60s. Situated in an affluent Toronto neighbourhood, from the outside it looks nondescript, but on the inside it’s every inch an artist’s home. One wall of the living room is packed floor to ceiling with books, artists’ catalogues, and hundreds of vinyl recordings; on another wall hangs a big abstract painting by Snow’s contemporary, Ron Martin, as well as one of Snow’s famous Walking Woman pieces, the profile of a woman rendered in stuffed cloth, bulging out from its frame; and in the middle of the room stands a shining black grand piano.

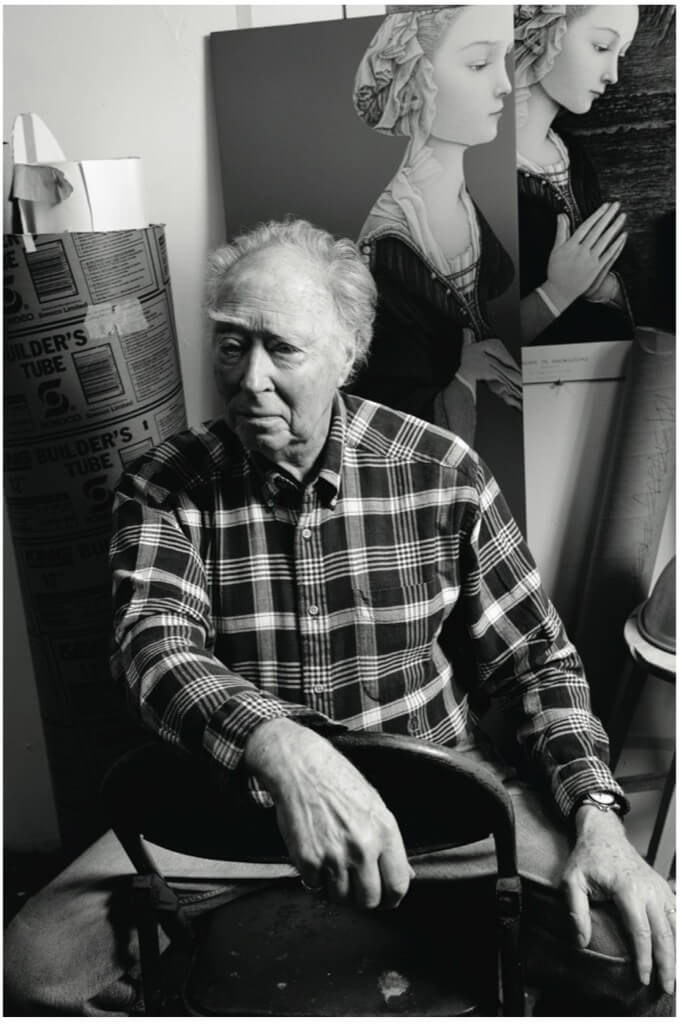

At eighty-two, Snow is, as he self-deprecatingly puts it, “ancient.” And he looks it. His once-thick sweep of hair has thinned to white wisps; and he is slightly stooped and brittle, his face and hands liver spotted, one eye drooping. But in his case, the depredations of age are misleading. His blue eyes are fierce, his wit quick and biting, his presence by turns playful and petulant, and his creative energy has scarcely flagged. When I visited him last fall, he had only recently returned from a summer at the log cabin he built himself in the Newfoundland bush—“There’s no phone or Internet out there, so I get lots of work done”—and he was sitting at his piano, demonstrating riffs he was thinking of playing at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art a few days later, as part of an exhibition by American artist Christian Marclay. Like Snow, Marclay has a reputation for combining visual art and music, and he asked Snow to improvise on clusters of notes in his recent photographs, images of which Snow had propped up on his piano.

“Here’s one!” he called out as his hands, as nimble as they are wrinkled, flashed across the keys. “But for this one, I think I’ll play the blues. I’ve always loved the blues.” With that, all smiles, he lit into a few bars of stomping blues.

Snow is a serious jazz musician, so much so that it’s hard to get him to talk about anything else. But he is also, and more significantly, the most influential Canadian artist—ever. There have been other important twentieth-century Canadian artists, but none of their work has achieved the reach of Snow’s, over the course of a career that has spanned more than fifty years. Painters of the stature of Tom Thompson, Lawren Harris, and David Milne are virtually unknown outside Canada. Montreal automatistes like Paul-émile Borduas remain in even deeper obscurity, as do William Ronald and the other members of Toronto’s Painters Eleven. The only artist whose international impact has been even comparable to Snow’s is Vancouver photographer Jeff Wall.

The reason for Snow’s impact is in part the promiscuity of his output: he has made abstract and figurative paintings, collages, sculptures, films, videos, photographs, multimedia installations, sound art, jazz albums, and every imaginable combination thereof. It is no exaggeration to say that for virtually every approach to art popular among younger contemporary artists, Snow was doing it decades earlier. In 1994, Dennis Reid mounted the Michael Snow Project, a massive retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario and Toronto’s Power Plant, which included four separate books on Snow’s work—one devoted to visual art, one to film, one to sound art and music, and one to his various writings. And he’s still at it. In 2009, the Power Plant mounted a survey of his video projections called Recent Snow. In February of this year, the largest survey of his art in Europe since his 2003 exhibition at the Centre Pompidou opened at Le Fresnoy in France; curated by Louise Déry of the Galerie de l’UQAM in Montreal, the exhibit includes a bilingual catalogue. As if to make a point, he is also working on three books.

“I hope we’re not just going to talk about the past!” he exclaimed, standing up from the piano and heading to the kitchen to pour us more black coffee from a big Thermos he keeps there. He was decked out in a checkered shirt and jeans, as though ready to go out and chop wood; despite his elite credentials—Companion, Order of Canada; Chevalier de l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres, France—he projects a homespun, boyish enthusiasm for his work. “I have a lot going on. I’m doing a lot of writing right now, because nobody knows more about my work than I do. And I started a new piece on the road to our cabin in Newfoundland. I did it panning back and forth over the rough road, all the rocks and puddles, from the back of my truck. It’s going to be called In the Way.”

Vintage Snow, even in his eighties an artist whose unselfconscious confidence allows him to pursue ideas as they come to him—the artist as jazz musician.

Michael Snow was born in 1928 in Toronto, to a francophone mother and an anglophone father, and while he lived as a child in both Montreal and Chicoutimi, summering at his grandparents’ cottage on Lac Clair, it was in Toronto that he grew up. He was already making paintings and drawings when, as a student at Upper Canada College, he discovered the jazz of Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, and the moody, supremely sexual sounds of Jelly Roll Morton. “So I started to play,” he says. “I was basically self-taught. My mother was a fine pianist, and she tried to take me to lessons, but I wouldn’t go; I’ve never been an easy one to teach.” Unbeknownst to the young Snow, the exotic, urbane, improvisatory nature of jazz had already made an impact on modernist paintings—from American artist Stuart Davis’s bright, whimsical city scenes of the ’20s, to dour Dutch painter Piet Mondrian’s swinging masterpiece Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43)—and jazz music and bands soon made their way into his early work. A small cubist drawing from that period hangs on the wall in his living room: a bunch of guys with big heads and wild, eager eyes set against a receding, fragmented cityscape. “This is a portrait of guys I was in a band with,” he tells me. Jazz was his introduction to the freedom and possibilities of art.

After high school, he attended what was then the Ontario College of Art, studying painting and drawing under director John Martin, who introduced him to the small Toronto art scene. Martin urged him to submit an abstract painting entitled Polyphony (“It was just a rip-off of the work of Mark Tobey,” Snow admits) to the Ontario Society of Artists’ annual juried show, and it was accepted, resulting in the first public exhibition of his art. After graduation, he worked for an advertising agency, made paintings, performed jazz music and travelled around Europe for the first time. Then, in 1955, he got an odd but defining break. The animated film producer George Dunning, who went on to direct the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, saw a small show of Snow’s drawings and offered him a job as an animator at Dunning’s Graphic Films. “I told him I wasn’t interested in the movies,” Snow recalls, “but he offered me the job anyway. Dunning wanted to hire fine artists, not just animators. With painting and music, I was inspired by example, so I had a lot of influences. But in film I had no real background, so I learned from the inside.” At least two important things happened during his brief tenure at Dunning’s Graphic Films: he met his first wife, the artist Joyce Wieland; and he made his first film, the animated short A to Z (1956).

It’s a quirky little film, but it implies themes that are consistent throughout Snow’s work: his close attention to the materials he works with, and his irreverent and often bawdy sense of humour. Shot in black and white and drawn in dark tones, it’s set against a background of two oblong windows and a swarming, sensuous ground. Two chairs face each other and begin hopping up and down, kissing each other at their fronts, flipping over and interlocking in a goofy yet ardent coital dance. By the second scene, domesticity literally creeps in. There is a house set on the horizon, and the two chairs sleep locked in a kind of cubist embrace, when in march a table and a vase. A to Z ends with the chairs politely pulled up to the table—a somewhat pessimistic allegory of the course of a relationship.

By the end of the ’50s, Snow and Wieland were married, and he was making a living as an artist and a jazz musician, exhibiting at the Bay Street gallery started by the Winnipeg-born frame maker Avrom Isaacs. It is easy to forget that Snow was an accomplished abstract painter. Lac Clair (1960), named after his childhood summer stomping ground in Quebec, is a work of oil on paper with taped edges. The piece’s central portion is a gorgeously brushed blue, the colour of water at twilight. The taped edges, on the other hand, underscore the constructed character of the image: this is a work that recalls the wind-whipped lake water typical in paintings by the Group of Seven, and that also looks inward toward its own nature as a work of art. But Snow was not by temperament an abstract painter, nor an artist oriented to working in a single style. He was always too restless for that, his mind crackling with too many different ideas.

“Even while doing purely abstract works, I was thinking about doing something with the figure,” says Snow. “So I started doing single figures without background on the wall. One day, I had this five-foot piece of cardboard, and I cut out a walking woman. I realized I had a stencil, so I decided to make a couple of copies. I then realized that what I had here was a female contour with a flat surface—and that I could do anything with it.” The prototype of the walking woman is a generic female form: breasts, a generously curving behind, her arm swinging back as she steps forward; and every subsequent iteration in the Walking Woman series, whether a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture, is based on that prototype. Snow has always insisted that the Walking Woman series has nothing to do with politics or feminism. “My subject is not woman or women, but the first cardboard cut-out of the walking woman I made,” he has said. “It’s not an idea. It’s just a drawing, and not a very good one.” But Walking Woman created a conceptual revolution in his work, allowing him to improvise in theme and variation, like a jazz musician, and, as he said, to do anything.

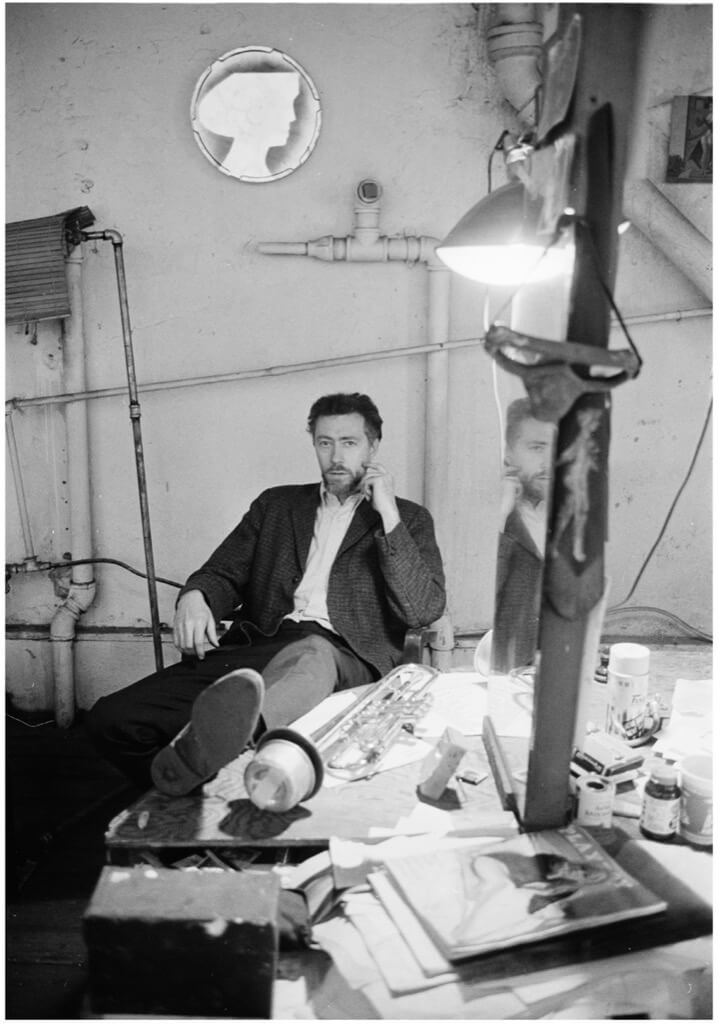

In 1962, Snow and Wieland, both represented by the Isaacs Gallery, were the power couple of Canadian art. But feeling the limitations of the Toronto art world, they were drawn to New York, which was immersed in one of the great creative periods in twentieth-century art: abstract expressionism, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and pop art. So they rented a loft in an industrial neighbourhood in lower Manhattan and made the move. And the Walking Woman series exploded.

Snow continued making paintings of the walking woman, in endless variations. Four Grey Panels and Four Figures (1963), for instance, consists of four different women, two facing outward and two inward, all in different levels of relief. One panel has a white ground, the figure in dark blue with a small orange figure inside it; another figure is just blank white canvas against a bright red ground; another is an outline with mottled daubs of light green, peach, and pink. Snow had taken a traditional theme in the history of painting and turned it into a rigorous, almost abstract element, yet at the same time had used a palette that suggested the influence of pop art. But the most significant development in his work at the time was his use of photography. He began taking pictures of sculptures of the walking woman placed randomly around New York. “I was never really interested in fine photography, and when I started using the camera I was just adding to the traditional tools of the artist.” Four to Five (1962), for example, consists of sixteen black and white photographs mounted on cardboard, depicting the walking woman on street corners, in stairwells, and in front of stores, with slightly bewildered-looking pedestrians hurrying past.

With his first full-length film, the thirty-four-minute New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), Snow moved the Walking Woman series into film, and introduced a new and important element: sound, in this case a landmark soundtrack featuring free-jazz greats Albert Ayler on tenor saxophone, and Don Cherry on trumpet. “When I made my first films in Toronto,” he says, “I didn’t really know that artists made films, but when I went to New York I found out about the underground cinema. We discovered a whole world of artists, and my conception of what film is or could be expanded.” Shot in black and white, New York Eye and Ear Control opens with typeset credits, then cuts to a dog romping through water with a walking woman set up on rocks. The film juxtaposes the walking woman in street scenes and on rocks in the water with images of real people, the sculptures always painted black or white. As the film progresses, the music undulates, often unruly and feverish. The concerns of New York Eye and Ear Control may be formal, but it’s hard to watch it without thinking that it’s at least partly about the relationship between the prototype of a generic women and actual women, between generic people and actual people, between rigid binaries and the porous fluidity of life. At one point, a woman compares herself with a cut-out of the walking woman, and the film culminates with a beautiful close-up sequence of a black man and a white woman making love.

Michael Snow is a note taker, an inveterate scribbler. He writes in much the same way he plays piano: quickly and freely, ideas pinging off one another. For each of his major works, he has written reams of notes, extemporaneously and by hand, many of them now archived at the Art Gallery of Ontario. He keeps two rooms as offices on the top floor of his house, and there are papers scrawled with notes and diagrams stacked on the desks, the floor, and the shelves. He has never lacked for ideas; indeed, he typically generates more than he can use in a given project, and they often end up resurfacing in later pieces. Wavelength (1967) is universally acknowledged as one of the breakthrough works in experimental cinema, one that has defined a whole minimalist genre of filmmaking called “structural,” but it is by no means clear from his notes that it was always intended to be as austere as it turned out to be. One of Snow’s unique strengths is his aesthetic flexibility; he adapts his style to a particular set of ideas, and then feels free to move on.

Wavelength is a single, forty-five-minute zoom shot from one side of a Canal Street loft to the windows facing the street on the other, accompanied by the sound of a sine wave that grows more urgent and mesmerizing as the film goes on. The action is without narrative, which does not mean it is entirely without incident: at one point, there is a crashing sound, and a man stumbles out and collapses on the floor, as though stabbed; at another point, a woman talks on the phone at a desk beside the windows. And there’s a lot happening visually. The screen flashes bright green, yellow, and blue, then focuses with a terrible clarity; sometimes the daylight disappears beyond the windows, so one can see the streaking lights of cars and buses passing by on Canal Street.

The camera’s movement in Wavelength is relentless but not fluid; one always has the sense that the halting zoom is controlled by hand. Eventually, the image hones in on the section of wall between the windows, where there is a drawing of two walking women and a photograph of water, as though the film were quoting both New York Eye and Ear Control and Lac Clair. “When I made Wavelength,” Snow says, “I thought it would be seen a few times, but when I showed it at Jonas Mekas’s 41st Street theatre everyone liked it, and Jonas said I should submit it to an upcoming festival in Europe.” It ended up winning first prize at the 1967 Knokke experimental film festival in Belgium, and Snow instantly became a major figure in the experimental film and art world.

It’s difficult to underestimate Wavelength’s impact, because it represented an entirely new approach to filmmaking: Snow was not using film to tell a story, nor as a means of making highly personal reflections; he was using it as though it were a sculptural material and he was creating a “temporal shape.” His next major film, La région centrale, is if anything more radical and visually spectacular. Whereas Wavelength is structured around a slow zoom, La région centrale is organized around the circular movements of a robotic arm designed to hold a camera directed at the austere landscape of northern Quebec. “It was part of exploring the medium,” he says, “and it seemed interesting to push it out from the body. I had used rooms before in Wavelength, because they have a human identification, so I got to thinking about open and wide landscapes. The machine was being made in Montreal, so I went up to Quebec City and looked at aerial photographs. Then we rented a helicopter and landed in a place where you can’t see any human life.” He adds, “I wanted it to be as if you’re seeing images you’ve never seen before.”

Three hours long, La région centrale represents a fundamental reimagining of landscape in the visual arts. Traditional landscape paintings, like those of the Group of Seven, imply a human point of view, and a horizon scaled to a human perspective. Snow’s film has no human point of view whatsoever, and its swirling, hallucinatory images, now close up on rocks and tundra, now expanding out onto mountain vistas, the horizon now on top and now on the bottom, seems to view landscape less as a stable place than as a delirious field of matter and energy.

Wavelength and La région centrale are intense, cerebral works. Snow’s other major films, made after he and Wieland moved back to Canada for good in the early ’70s, display his more whimsical side. The four-and-a-half-hour “Rameau’s Nephew” by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (1974) opens with Snow whistling riffs in front of a bright red background, and goes on to an extended sequence of people at a tea party speaking their lines backwards. *Corpus Callosum (2002), his first digital work, continued his exploration of the nature of mind and perception, this time focusing on the ways the brain manipulates information to create images. Here, he worked with a computer programmer to generate images of people in a Toronto office that stretch, squeeze, distort, and randomly vanish. “*Corpus Callosum actually ends with a little sketch I did when working at Graphic Films in 1955,” Snow tells me, “so in a way it was a return to animation.”

The exhibition at Le Fresnoy is not an exhaustive retrospective, but rather focuses on Snow’s media works: photographs, video projections, video installations, sound installations, and films. This is partly pragmatic; Snow’s output has been so vast, all over the place, and at times frankly uneven that it’s hard to assemble it into a single, coherent exhibition, a problem that plagued the 1994 show at the AGO and the Power Plant. It is also consistent with Le Fresnoy’s singular mission. Located in a former adult holiday camp near the Belgian border, it is an innovative art school dedicated to the electronic and multimedia arts. “It’s still a big show,” Snow insists as he riffles through the disorder of his office, pulling out one of the many floor plans for the show he sketched with a ballpoint pen. The exhibit amounts to a powerful argument for Michael Snow being the original multimedia artist, not as a political position or even an aesthetic one; he is refreshingly free of ideologies. He is a multimedia artist because of the range of his curiosity, and because his ideas do not fit snugly into any particular idiom.

Of the more than thirty works included in the exhibition, the earliest is Sink (1970), a slide projection of an old loft fixture luxuriantly filthy with paint, ink, and brushes; it resembles an homage to the old style of making art. Solar Breath (Northerm Caryatids) (2002) is a video projection of wind and light passing through the shimmering curtain of an open window, an image that feels both lyrical and elegiac. And Condensation. A Cove Story (2008) is a time-lapse video of light and weather passing in a Maritime landscape. The show’s singular features, however, are two powerful sound installations: Diagonale (1989), which revives the sine wave from Wavelength, but at a low timbre heard in different ways in a sixteen-speaker sound environment; and Sinoms (1989), in which Snow had some twenty voices with French and English accents recite a complete list of the mayors of Quebec City. The effect is by turns like that of an incantation and of a cacophonous choir. He uses sound in much the way he uses film images in Wavelength and La région centrale: as a sculptural material through which he can create new experiences, associations, and possibilities.

One evening last October, with the hoopla of the Toronto International Film Festival just over, the local experimental film community gathered in one of the immaculate new theatres in the Bell Lightbox to view an equally immaculate new print of Wavelength. Purchased from the Canadian Film Makers Distribution Centre, it will be part of the TIFF Cinematheque’s archive of important Canadian films, and is among the few non-narrative works to be voted one of the 100 essential films of all time for Essential Cinema, the Bell Lightbox’s fall 2010 series.

After the screening, TIFF programmer Andréa Picard introduced the audience to Snow and Annette Michelson and P. Adams Sitney, two influential American academics who were early champions of his work. Friends for more than forty years, the trio shot the breeze about the trenches of the ’60s New York avant-garde. But one could sense that Snow was impatient, fidgeting in his chair; I could almost hear him barking, “I don’t want to just talk about the past!” While some people think Snow would have achieved still greater acclaim had he remained in New York, he doesn’t feel nostalgic for his years there; he’s too preoccupied by what he is doing now.

He has had a long and close affiliation with the film festival. In 2000, he was commissioned to make a short film entitled Prelude, to be shown before some of the festival’s screenings. And he has been a regular attendee, if only to remark upon the myriad instances in which someone used an idea he had first. He was also supposed to execute a public art project called Tower of Film for Festival Tower, the condominium behind the Bell Lightbox, but in August he filed a $950,000 lawsuit against Ivan Reitman and the Daniels Corporation for backing out.

Snow possesses a significant reputation for making public art. In Toronto alone, he has created the flying geese in the atrium of the Eaton Centre; the rowdy fans bursting from the facade of the Rogers Centre; and the eerie images floating in plasma screens set in false windows above the Pantages hotel. “I’m also working on a public work for the Trump Tower,” he says. So he has already made his mark on his native city, but Tower of Film, with its witty evocation of Leonard Cohen’s darkly ironic “Tower of Song,” held special significance for him. After all, who better to do a public sculpture for a project largely devoted to celebrating cinema as an art? “Tower of Film was supposed to be a large, two-sided film strip with sprockets and an optical track,” he says. “The images in the frames would be of a camera panning up and down the building—and they were to be lenticular, which means that any movement by the spectator would change the image. It’s a form of holography.”

Snow agreed to let the Daniels Corporation put his name forward to the City of Toronto on the understanding that he was being commissioned to create the public art project, subject to the city’s approval. According to Snow, Daniels received special permission from the city to make the commission without the usual public competition. After the commission had been approved, there were several meetings to discuss his ideas, and at the last of them he made a presentation which was greeted enthusiastically by several people, including Ivan Reitman, and Bruce Kuwobara, the architect. A few weeks later, Niall Haggart, a Daniels vice-president who had been present at all the meetings, sent Snow a letter saying that they were not going ahead with the project. There has never been any explanation for this abrupt cancellation.

The legal merits of Snow’s case (he never signed a contract) are unclear. But his perseverance in the face of Reitman’s and the Daniels Corporations’ considerable resources—Snow may be a Canadian icon, but he’s not rich—exemplifies his idiosyncratic hybrid of naïveté, tenacity, and natural self-confidence. “I don’t care about the money,” he insists. “I just want to get the work made.”

Michael Snow is at an age when it would make sense to be thinking of his legacy, but he is remarkably in the moment. The opposite of the tormented artist, he still clearly loves being Michael Snow. His busy fall and winter have included working trips to New York, Philadelphia, Lausanne, Lisbon and Le Fresnoy, with a few musical gigs thrown in for good measure. By next summer, he’ll be back in his cabin in Newfoundland, where, without distraction, he can make art. Maybe he’ll continue his exploration of the rocks and mud and grass on the road up to the cabin. Maybe he’ll work on a project he wants to do, using photographs passed down from his grandmother of life in early-twentieth-century rural Quebec. We can be sure he has plenty of other ideas as well, scribbled somewhere amid the notes stacked in his office.

This appeared in the March 2011 issue.