I’m seven years old, and under my bed is a go bag for when I head over the wall. Inside the green plastic garbage bag are a few stuffed animals that I take out every night and return each morning. A fraying rabbit, Winnie-the-Pooh, a Rin Tin Tin dog. It’s not always the same three that make it into the go bag. I line up all my stuffed animals and decide which I can take with me. My older sister watches but never says a word. She knows there is no way out, but I still see potential openings. Our tall bedroom window looks out onto the back porch and has a wooden screen that can be removed only from the outside. When no one is watching, I sneak around to the porch and loosen as many swivel clips as I can reach. At the grocery store, I wander off from my mother and six older siblings and try to look like a child who needs rescuing, like I wouldn’t make a sound if someone snatched me away.

Nobody takes the bait. It will be fifty years before I make it over the wall on my own.

It was 1968 and I was stranded deep in the wilds of New York’s Westchester County with my parents, five brothers, sister, and 250 boys who had been sent to Lincoln Hall by the state to be rehabilitated for their petty crimes and truancy. Lincoln Hall was well camouflaged. Its expansive property was bisected by Route 202, a highway bounded by old stone walls that meandered through the southern tip of New York state and across the Hudson River. The Lincoln Hall campus encompassed a new chapel, a gymnasium with gleaming hardwood, an outdoor quarter-mile running track, a manicured baseball diamond, a swimming pool, handball courts, and a movie theatre. The entire property, on both sides of Route 202, was surrounded by acres of farmland.

Lincoln Hall was run by the De La Salle Christian Brothers with a handful of lay staff. Our family of nine had moved out of the Bronx two years earlier. Our parents, Ed and Pat, sold the brothers on a package deal—my mother, Pat, would be the school’s librarian, and Ed the new assistant vice-principal. Neither had the formal requirements for their jobs. Pat told anyone who asked that she was inspired by the Hollywood blockbuster Boys Town, starring Spencer Tracy as the real-life Father Flanagan. Ed looked the part of a man who could keep troubled youth in line, with his regulation Navy crewcut and the American bald eagle on his forearm. When we first arrived, Ed called Lincoln Hall a “country club for delinquents.” His office was on the main floor of the Fishbowl, an L-shaped red-brick building with wide glass double-doors framed by a semicircular portico. Near Ed’s office were the locked cells for the boys who acted up or tried to run away. When a Linky kid jumped the wall, it was Ed’s job to fetch him back and drop him in the cells for a few days.

Pat had negotiated our housing on Lincoln Hall property as part of the package deal. We lived on the ground floor of what was then the Lakeview, a 100-year-old house without lake or view. Ed sunk a pole into the front lawn and raised the American flag every morning. Every night, he picked two of his children to lower the flag and fold it into tight military triangles. On Sunday nights, Ed ironed his five white work shirts, then polished both his pairs of black penny loafers and both his pairs of brown penny loafers, in that order.

Life at the Lakeview was a roulette of transgressions. It always started the same way. Ed and Pat lined the seven of us up in the kitchen in age order. Ed promised nobody would get hit if we told him the truth. He wanted to know who broke into the locked fridge, who stuck gum on the dog, who left the car window open, who ate his pistachios, moved one of his razor blades, busted the couch, put a hole in the screen door, or drank the Vicks cough syrup. Sometimes there was no transgression at all.

Ed began at one end of the line and worked his way down to me. “Was it you?” Each No bought you a crack across the side of your head, clipping your ear with his Knights of Columbus ring. My oldest brother’s hands would fly up to cover his inflamed face, a scalded combination of fear and confusion. When my brother cried, Ed sneered, “Why are you crying? Tell me why you’re crying.”

Ed was a lefty but swung right with my second oldest brother, the only redhead in the lot, born with a misshapen ear and a birthmark on the side of his head. The ear was off limits. That was Pat’s rule. Pat liked to tell the story that she had seen her husband cry only twice: the first time he saw his son’s birthmark and when JFK was assassinated. Down the line, my brother with the bullet-shaped head, the beefiest of all the boys, would jut his jaw out to enrage Ed even more. It always worked.

Once, the middle brother, with sanguine hazel eyes the size of half dollars, jumped the gun and confessed just to get it all over with. It didn’t work. “You think I’m a fool?” My sister stared at the ground, shoulders rounded, plucking at the ends of her too-short shirt sleeves and hiccupping from fear and tears. “I bet you feel sorry for yourself.” I could feel our collective rage gather and dissolve with each pass up and down the line.

Ed talked a lot when he beat his kids. He liked to lean in close, looking at your forehead instead of your eyes. With spittle at the corners of his mouth, he would remind you that you had no problems. “You think you have problems? You don’t know what a problem is. I’ve got real problems. You’ve got it made.”

After making his way up and down the line a few times with no result, Ed would turn to Pat and begin their canned exchange. What followed was part Beckett, part vaudeville.

“How did this happen to us, Pat? How did we get saddled with seven lying sacks of shit?” Pat would sigh and cock her head to one side, resigned, heartbroken. “To have to raise savages. A pack of animals. Thieves. Did we miss something? The roof over their heads, the food on their plates—Isn’t it enough?”

When they’d run through their script, Ed would pull out the big guns. It was the final, violent punctuation of the battering. Vile slurs we knew were wrong—vile even for the time we lived in. “I go to work every day and have to deal with n—ers and s–cs. Do you think I want to work with those animals? Do you think your mother wants to work with n—ers and s–cs and then come home to this? You kids? Seven lying sacks of shit?”

Ed and Pat would take a well-timed smoke break so we could spin a butter knife on the kitchen table to choose a victim. We watched the beating that came next. Afterward, with scarlet faces and ears ringing, we were piled into the car for King Kone ice cream, careful not to drop a sprinkle on Ed’s car seats.

At home, my family was a cauldron of threats and violence. Outside, America was seething.

If Ed was methodical in his violence, Pat was chaotic, hijacked by despair. She brandished a shotgun at her children. She grabbed knives from the kitchen and accused us of wanting her dead. She tore through the house at odd hours, cursing the man who had stuffed her full of babies and ruined her life. She would leave the house in her nightgown with an empty suitcase to sit at the end of the long gravel driveway, waiting for one of the boys to coax her back inside. Ed always played possum, asleep in his La-Z-Boy, until she spun herself out.

We were told, “What happens in this house stays in this house.” They needn’t have worried. At six, I stopped speaking for a while. I couldn’t drag a single word out of my mouth. I was terrified Ed and Pat were going to hell. I prayed for my parents and did my best to sound sincere. I worried that I couldn’t be a good person in a family like this and that maybe we’d all go to hell together. At St. Joseph elementary school, we stood with our hands over our hearts, facing the American flag, and recited the Pledge of Allegiance every morning. The nuns told us how to be good: carry orange UNICEF boxes at Halloween, pray for African babies, keep our hands and feet to ourselves, keep our mouths zipped in the hallways, and most of all, never lie.

The first lie I ever told myself was that I couldn’t run away from home because I loved my family. I told myself that my brothers and sister would never survive without me, that I mattered to them. I ran sentences in my head, practised lies to defend against the futility of my useless go bag. I told myself that I loved my father, and that I loved my mother, even when they beat me.

I did love my family, but that wasn’t why I stayed. A seven-year-old has nowhere to go.

On October 25, 2018, after more than three decades living and working in Canada, I walked into the American embassy in Ottawa and renounced my American citizenship. As instructed by my lawyer and embassy officials, I carried only a slim valise. Inside were a fistful of US government forms, my American passport for surrender, my American birth certificate, my Social Security card, and my Canadian passport to prove I would not be stateless after my renunciation. The valise also held a self-addressed express-post envelope, to receive my Certificate of Loss of Nationality once the US State Department had stamped its final approval, and a cashier’s cheque for $2,350 (US)—my exit fee.

My formal renunciation was the final step in a byzantine two-year journey that began when I applied to become a Canadian citizen a few months before the 2016 US presidential election. My creeping fear had evolved into grim certainty that Donald Trump would win. I was desperate to shed all birthright ties to my country.

Until the 2016 election, I’d always thought of my childhood as an outlier, so extreme that I couldn’t shoehorn it into a larger narrative. It wasn’t until Trump’s transgressive campaign—the ominous stalking of Hillary Clinton on a debate stage, the grotesque pantomime of a disabled reporter and fusillade of racist statements at his rallies—that I recognized my family as a diorama of America’s dysfunction. As I watched Trump lie in real time, disavowing reality while inciting violence, I realized that my family shared the same superpower: we could hide in plain sight, lie to ourselves, and make others believe it. And, just as Trump would disproportionately attack anyone who threatened to unmask him, we would go to any lengths to protect our lies.

Once, I walked into the kitchen just as Pat whipped her Bloody Mary at Ed’s head. She missed, and the tumbler exploded against the wall behind him. I was certain she had shot him. One of my brothers tried to comfort me and said this kind of thing happened in all families. I knew that wasn’t true. When Ed and Pat stopped eating meals with us and instead brought their plates of better food and pitchers of cold Tom Collins into the living room each night, I knew that that wasn’t normal either.

When Ed and Pat trotted us out in public, people would marvel at their outsize brood and how well behaved we were, how scrubbed clean we looked in Pat’s handmade clothing. They couldn’t hear Ed’s sotto voce in our ears, his breath on the backs of our necks as he’d lean over with a smile on his face if anyone was acting up and warn, “Fuck with me now and you’re fucking with your heartbeat,” or, “I’m going to lose my shoe up your ass when we get home,” or, “I’m going to knock you into the middle of next week.”

At home, my family was a cauldron of threats and violence. Outside of the Lakeview, America was seething. Early in 1968, South Carolina Highway Patrol officers fired into a crowd of student protesters at South Carolina State University, a historically Black school in Orangeburg. Three Black students were shot dead. In April of that year, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination ignited widespread rioting that escalated into shoot-to-kill orders. Antiwar demonstrations on college campuses spread across the country even as the US increased troop deployment in Vietnam. The Democratic National Convention in Chicago turned into a televised brawl. Richard Nixon ran on a “law and order” campaign that won him the 1968 presidential election, then dog-whistled about the rise of Afrocentrism and the Black Panther Party.

In 1972, right before his second term, Nixon’s White House was under investigation for a break-in and phone-tapping at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, in the Watergate complex. Beginning on May 18, 1973, the Watergate hearings aired live on all three major US networks. I was eleven years old and glued to the TV along with tens of millions of Americans who watched live or stayed up half the night to catch the rebroadcasts on public television.

When the Watergate hearings ended, in August, Ed had already lost or quit his job after seven years at Lincoln Hall (he never said which), and we moved to Connecticut. We bounced from one rental to another while Ed commuted back to Westchester to teach grade seven at Somers Middle School. The job came with a pay cut and a sixty-four kilometre daily round trip in the middle of America’s crushing recession and national gas shortage. In Connecticut, Pat wallpapered and sewed drapes for wealthy homeowners in Newtown, Bethel, Brookfield, and Darien.

At the end of our first year in Connecticut, Nixon resigned to avoid his inevitable impeachment. Vice-president Gerald Ford was sworn in as president, promising Americans that their “long national nightmare was over.” A month later, he pardoned Nixon. President Ford’s message was clear: Nixon was just a bad dream; the greatest country in the world doesn’t have paranoid presidents who order criminal acts and keep enemy lists.

In 1975, I started high school. My parents bought a house on Washington Avenue in Danbury with the student loans of their older children. Danbury was a small city surrounded by prettier towns, a dreary place pocked with abandoned hat factories. If you bought a hat in the early decades of the twentieth century, it was likely made in “Hat City” by European immigrants. But the industry was already in decline: by the early 1950s, when headgear began to go out of fashion, Danbury was washed up.

After buying their new home, Ed and Pat’s first act of community involvement was to sign a petition to bar a Black family from buying the house next door. Black families were largely confined to the public housing projects on Eden Drive and Laurel Gardens. Throughout the 1970s, race riots were a regular occurrence at Danbury High School, violent brawls that landed at least one student in the hospital. In 1979, fifteen years after the Civil Rights Act was passed, a member of the KKK was distributing pamphlets on the local state university campus.

I got a job as a cashier at the Danbury A&P just as Ronald Reagan resurrected the ugly myth of the welfare queen in his unsuccessful presidential run of 1976. Black families who arrived at the store with food stamps and WIC vouchers were greeted by security at the front and in the aisles. Deli cold cuts were wrapped and labelled in sets: one of three, two of three. Cashiers were told to check under Black toddlers sitting in shopping carts if three of three was missing.

I promised myself that there would be a day when I would tell the truth. I could be a good person.

By the time I hit my teens, I hadn’t prayed for my parents in years. I did, however, agonize that my own moral compass was in jeopardy. Deceit—about where I was going, whom I was seeing—was required every time I wanted to leave the house. Pat insisted that my friends were laughing at me behind my back, that they were not to be trusted. Late at night, I would roll the lies I’d told over in my head like worry beads. I promised myself that there would be a day when I would tell the truth. I could be a good person.

By 1980, Reagan was elected president and the house in Danbury turned out to be a lemon. The back half was below ground level and flooded on schedule. Mushrooms sprouted in the rust-coloured shag carpet, and our family was keeping pace with the decomposition. My second and third oldest brothers were both married and divorced before they hit their late twenties. My eldest brother never returned home after attending university in Nova Scotia. My middle brother had a psychotic break and landed in the locked psych ward at Danbury Hospital. My brother’s doctor recommended that Ed and Pat participate in his treatment and attend family therapy. They wouldn’t risk being exposed if details about our childhoods emerged, so my brother was left on his own for three weeks at the hospital. The seven of us scrambled away from one another. In 1981, when I left to attend university in Toronto, only two of my siblings remained at home.

A few years later, it was just Pat and Ed on Washington Avenue. They opted for a second chapter. In 1984, they came to Canada and soared through the immigration process on the wings of a recently passed bill to extend funding to Catholic schools in Ontario. They rented an apartment in North York and were promptly hired by the Toronto Separate School Board (today the Toronto Catholic District School Board) as special education teachers. Pat taught the primary grades in downtown Toronto and Ed taught at a high school just around the corner from their apartment building.

Ed delighted in being the brash American with the Bronx accent and badass tattoo. His students loved him. Among the stories he liked to tell was the time he stood on his desk in a toga to teach Julius Caesar, and how he had coached the baseball team wearing the Yankee pinstripes. Ed asked his students to help him out when school board evaluators came around during his probation period. He would ask the class a question, and every student would raise a hand. A right hand signalled that they knew the answer; a left hand would never be called on. One hundred percent participation with an astounding success rate.

Being an American in Canada was a lot easier than being one in America. I picked the best version of the American mythos and stuck with that until I couldn’t. I was breezy, opinionated, and confident. In my work life and with friends, I presented my Irish American family as a sprawling, grittier version of the Kennedys playing touch football on the front lawn—only our version included parents who didn’t take us to the hospital when we ended up with broken bones. The best lies are rooted in parallel truths.

I didn’t stay in touch with anyone from the States outside of a few family members. And, even though they had relocated to Toronto, I didn’t see much of Ed and Pat either. Instead, I settled into my Canadian life. After university, I became a landed immigrant. By the late 1980s, my work as a producer for the CBC took me to Alberta, Quebec, and Ottawa. My magazine writing took me to Saskatoon and to First Nations communities in Labrador. After my son was born, in 1991, I knew I would never live in the United States again. I couldn’t imagine uprooting him—or myself, for that matter. Still, I never considered renouncing my American citizenship or formally becoming a Canadian. Occasionally, a friend would ask why, and I never had a good answer.

I didn’t spend any significant time in the US again until the summer of 2001, when Esquire sent me to Florida to write about Nathaniel Brazill, a fourteen-year-old Black boy being tried as an adult for the fatal shooting of his white seventh-grade teacher, Barry Grunow. On the morning of May 26, 2000, Brazill had been suspended for throwing water balloons. He was sent home and returned with a handgun he had found at his grandfather’s house. Brazill later told police he had just wanted to say goodbye to two girls before the school year ended. When Grunow wouldn’t let him into the classroom, Brazill took the gun out to scare his teacher. As Brazill later told police, he didn’t know what had happened after the gun went off. “Well, like, I couldn’t see ’cause my eyes started to get real watery and stuff, so I just ran. After I seen the blood, I ran.”

Brazill spent the next year awaiting trial in the Palm Beach County jail. Through the Plexiglas, I could see a whisper of hair over his top lip. He had also filled out: he was four inches taller and twenty pounds heavier. His defence attorney knew what this meant. Brazill had gone from being a boy to a “thug.” His story was going to end only one way.

Brazill was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to twenty-eight years in prison, where he remains today. His story was in the queue for publication when the Twin Towers fell. Esquire held the piece. It wasn’t the right time. The right time never came.

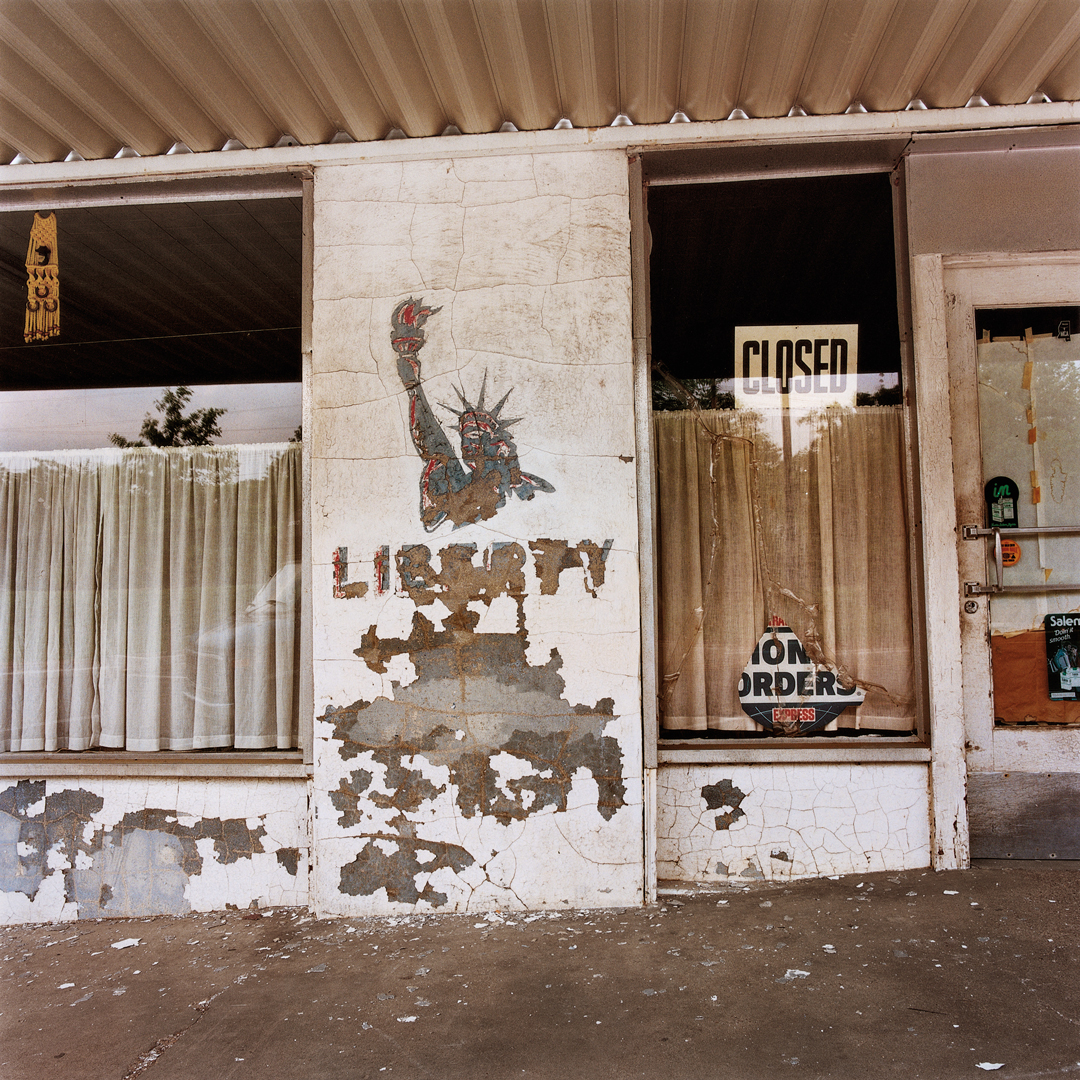

After Nathaniel Brazill and 9/11, the distance between myself and America cracked open. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, I bought an American flag and hung it on my front porch in Toronto. It was a strange impulse, a phantom-limb spasm of patriotism that I thought had been properly excised. It was also an echo of my childhood attempts at prayer, an obligation to feel what others felt.

Whatever cell memory made me hang the American flag quickly fizzled. I didn’t hang the flag on the one-year anniversary of 9/11 or any year after that. What followed for America was the steady erosion of its meticulously crafted image on the world stage. A bad-faith pursuit of nonexistent weapons of mass destruction led to the disastrous foray into Iraq. At home, the Patriot Act and Homeland Security expanded the government’s surveillance powers. Police departments were militarized with equipment off-loaded from the US Army—equipment used in full force today. When Americans took to their streets last spring to protest the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, they were greeted by police officers straight out of Call of Duty: bulky monochromatic uniforms, body armour, tactical vests, flak jackets, helmets, visors, and semiautomatic assault rifles at the ready.

When I joined Facebook, in 2010, a window into the America I’d left behind opened with friend requests from my Immaculate High School class of 1979. Dozens of my Catholic schoolmates now identified as conservative evangelical Christians. I remember being unsettled by the vociferous religiosity that cluttered my Facebook feed: prayer chains, personal testimonies about God’s love, and anti-abortion rhetoric. The burgeoning Canadian in me noticed that almost every American political speech ended with the command God bless America. By 2015, the conspiracy theories about Barack Obama’s US citizenship had turned into misogynistic attacks on Hillary Clinton. My New Jersey cousins were vocal Trump supporters. By the summer of 2016, I’d worn out the unfriend button, and my application for Canadian citizenship was in the queue.

For people mortified by Trump’s victory, those years were a psychic grinding of gears.

Trump’s victory, on the evening of November 8, 2016, was a flash-bang grenade. When the country’s senses came back, president-elect Donald Trump was lumbering across the stage with his family in tow. Clinton was the winner of the popular vote, with almost 66 million votes, but it didn’t matter. Trump’s gleefully nihilistic campaign had earned him almost 63 million votes. He’d promised a border wall, maligned Mexicans, advocated a Muslim ban, stoked violence against protestors at his rallies, threatened to jail Clinton, and bragged about sexually assaulting women. I was on the phone through much of the night and into the early morning with my middle brother in Connecticut. He’d been reassuring me for weeks that Trump didn’t have a hope in hell; Clinton would mop the floor with him.

When Trump won, my brother said he’d be impeached within a year. He wasn’t alone in this belief. The day after Trump’s inauguration, the Women’s March drew millions of protestors in cities across the country. Similar protests continued for the next two years. It seemed that many Americans could not reconcile Trump’s ascendance with their ideas about America. The dissonance was profound.

On February 22, 2017, about a month after Trump’s inauguration, I took my oath of Canadian citizenship along with dozens of others at Scarborough Town Centre. It was standing room only, with friends and family members of the soon-to-be new Canadians crowded together along the back and side walls, holding tiny Canadian flags. The excitement was infectious, and almost immediately, I was caught off guard by how emotional I felt. What had begun as a calculated off-ramp to unload my American citizenship had deepened into something else when I wasn’t looking. The presiding judge kept things short and sweet. She congratulated us and suggested we get to know our neighbours, make new friends, and visit Canada’s provincial parks.

And so it was as a Canadian that I watched the midterm elections in November 2018 and watched Trump roll back Obamacare and withdraw from the Paris Agreement. It was as a Canadian that I watched him hand out tax boons for the rich, withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal, put children in cages at the southern border, embolden violent white supremacists in Charlottesville, attack the press, shelter US enemies, and alienate allies.

While Trump napalmed the sociopolitical landscape, the mainstream media—CNN, the New York Times, the Washington Post—paddled in circles, wilfully pretending, perhaps even believing, that Trump would transform into something more presidential—that he’d stop slandering his opponents, colluding with Russians, or egging on white supremacists. He never did.

For people mortified by Trump’s victory, these years were a psychic grinding of gears. Seeing but not believing. Predicting nonexistent tipping points—“This is not who we are”—and waiting for the country to be rescued by a rotating cast of heroes who never showed up: James Comey, Robert Mueller, John Kelly, James Mattis, Susan Collins, any honourable Republican. It was a cruel political Ferberizing. But I wasn’t surprised. I was watching my childhood, writ large.

With my Canadian citizenship in hand, I hired a lawyer at the end of May 2018 and slogged on with the bureaucratic waterboarding of renouncing my US citizenship. I struggled to remember exact dates and the addresses of where I had lived and worked in the United States almost four decades ago. I was unnerved by sinister warnings about the repercussions of lying or trying to evade taxes. They demanded the highest balance in every one of my bank accounts over the past five years (Form 114a) to screen for possible money laundering. I had to provide the name and credentials of my lawyer (Form G-28). I had to fill out a Non-Resident Alien Income Tax Return for each of the past five years (Form 1040NR). With each completed form, I revealed more of myself to the American government.

To complete my formal renunciation, I was instructed to appear at the American embassy in Ottawa on October 25, 2018, at 1 p.m.—six months after I began the process. The embassy looks like an above-ground bunker, rising at an illusory slant and bulwarked by concrete barriers, a modern-day portcullis to prevent anybody from driving in. Cameras are mounted like turrets. The interior is muted in comparison. I was greeted outside the front door by a guard who waved a security wand over me. Inside, a second guard checked my valise and pointed me down the hall, to the cashier’s wicket, to hand over my bank draft. After a short wait, vice-counsel Angela M. Mora went through my personal documents and government paperwork sheet by sheet. She then had me read and sign form DS-4081, Statement of Understanding Concerning the Consequences and Ramifications of Renunciation or Relinquishment of US Nationality. The statement reiterated warnings about tax evasion, becoming an alien, and America’s power to extradite me back for a criminal offence.

Finally, the question I’d been warned about by my lawyer and by other expats who had already renounced: “Why are you choosing to renounce your citizenship today?” I had been given straightforward instructions for this exact question. I was to make it clear that I had no plans to ever work or live in the United States again and I no longer wanted to keep my citizenship. Instead, I prattled on about how I had come to love Canada. I blurted out that I didn’t hate America and I might even feel sad about giving up my citizenship, but my life was in Canada now.

I was seven years old again, trying to convince myself that I loved the country I was escaping. Vice-counsel Mora looked relieved when I stopped talking. She stamped the final sheet of paper before confiscating my passport.

I renounced my American citizenship so I could stop lying, about my family and about America. The cherry-picked mythos of my American childhood that I’d imported with me to Canada didn’t hold up over time. It didn’t hold up with my siblings either. A brutish childhood is a burdensome thing to have in common. One of my brothers tells people his whole family died in a tragic plane crash. I appreciate the economy of his solution. Another brother simply disappeared. My family fled to three different countries and two continents. The shortest distance between any two of us was a five-hour drive we never made.

President joe biden ran a successful campaign on the myth of the American character. He promised the American people that he would restore the nation’s soul as well as its standing at home and abroad. He called Trump’s presidency an “aberrant moment in time” and reassured exhausted voters that it wasn’t too late to turn things around for the country.

More than 81 million Americans voted for Biden, the most votes a candidate has won in any American election. Trump garnered the second highest number of votes, almost 74 million—nearly 10 million more than he won four years ago. By any calculation, this election was not a repudiation of Trump or his policies. His 2016 declaration was prophetic: “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose voters.” Trump is the end-stage manifestation of America’s malignant self-deception. Biden’s victory doesn’t change this diagnosis, and his job got harder. On January 6, Trump fortified his supporters with another helping of lies about a stolen election, then watched them storm the Capitol Building, an attack that has so far claimed five lives and telegraphed America’s wounds around the world.

In a nation riven by racial pain, discrimination, violence, and poverty, the biggest threat is not what divides Americans but what they have in common: the abiding lie that America is the greatest country in the world.

In 1991, my sister wrote a letter to Ed and Pat from England. In it, she catalogued the horrors of her childhood and the shadow it cast over her present. I got a copy of the letter at the same time and dreaded what might happen next. I didn’t hear from either Pat or Ed, and a week later, I got a call from a police officer telling me my father was dead. I assumed Ed had killed himself. It wasn’t until I got to Scarborough General Hospital, where my mother was waiting, that I learned he had died of a heart attack. He was sixty-two.

Ed had hidden the letter from Pat. My second oldest brother told me I had to find it before it killed Pat as well. After the funeral, my siblings went home to England, Vancouver, Ottawa, Chicago, California, and Connecticut. (There were fewer of us together in the same room when my mother died, in 2003.) It was just Pat and me and my six-week-old son left in Toronto. For weeks, I got regular phone calls from my brother asking if I’d located the letter. I hadn’t, because I’d never looked for it.

Months after Ed’s death, Pat called me, crying uncontrollably, and I knew immediately that she had found the letter. I wondered what had taken her so long. I went to see her at her apartment, in Don Mills, where we sat across from each other at the dining room table. She asked me if it was true, what my sister had written in the letter. I understood that the question was a dare; Pat didn’t look away until I answered, Yes. I remember her hands resting lightly on her teacup. She looked past me, out the window, and told me she couldn’t remember anything like that ever happening in our family.

February 19, 2021: A previous version of this story misspelled Lash LaRue’s name in a caption. The Walrus regrets the error.