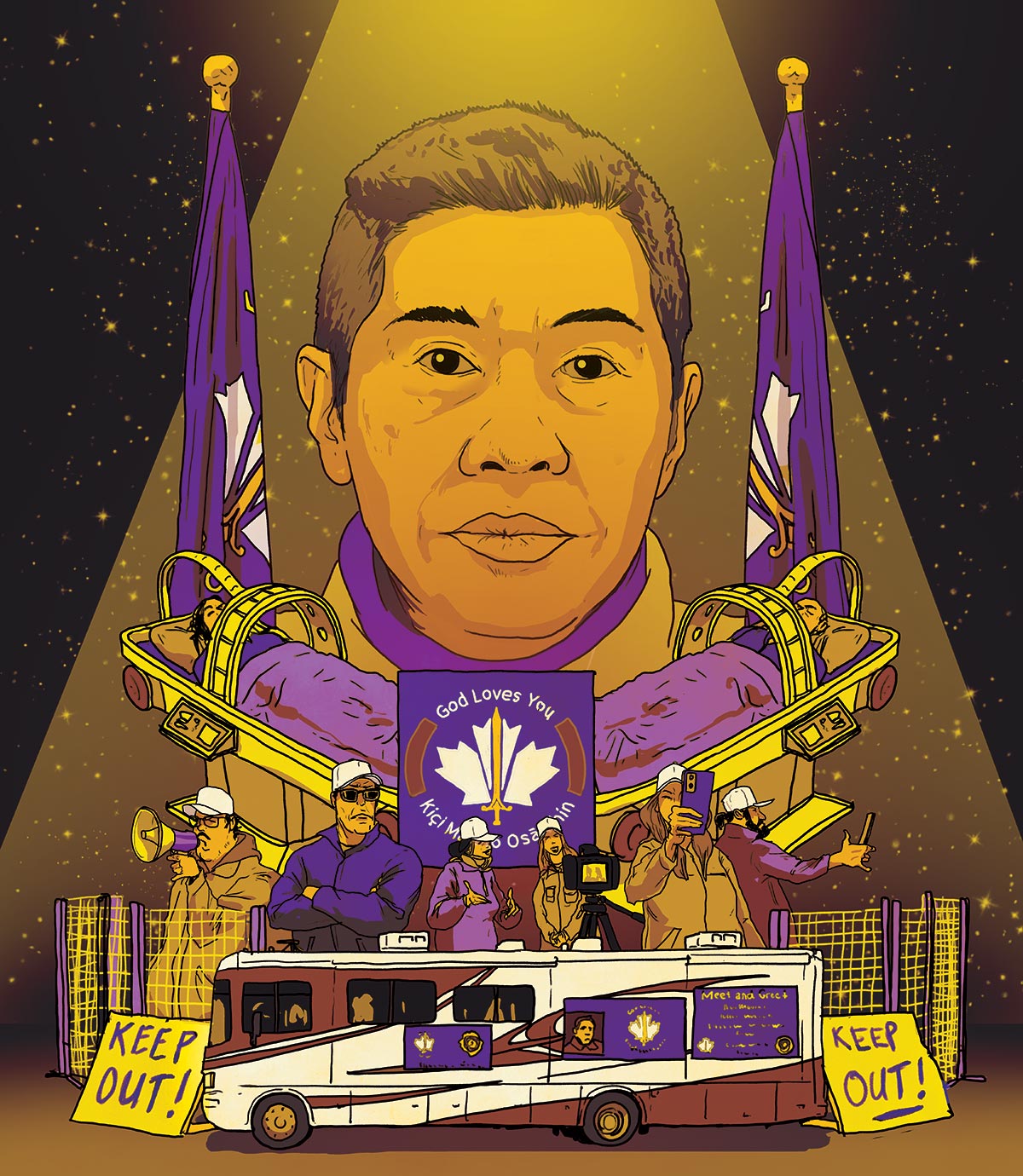

Few people drive into Richmound, Saskatchewan, without purpose. The town, with a population of just over 100, lies around seventy-five kilometres from the Trans-Canada Highway, near the Alberta border. So when a caravan of RVs and motorhomes drove into town one day last September, it caused quite a stir. The vehicles were adorned with purple and white flags featuring a white maple leaf and golden sword, portraits of a woman’s face, and signs referring to her as the “Queen of Canada.” Residents watched as the convoy turned off the main road, past the sole church and community centre, and into the driveway of the former school building. The group wasn’t just passing through.

The woman pictured on the side of the vehicles was Romana Didulo, believed to be one of the most active conspiracy figures in North America. She and her followers had been wreaking havoc across Canada and online for years—propagating fictions about COVID-19 vaccines, sparking sometimes violent protests, and spreading conspiracies popular with QAnon, an umbrella term for the pro–Donald Trump theory that the world is run by a cabal of pedophiles who worship Satan. Didulo saw herself as Canada’s true leader, issuing bizarre “royal decrees” for her subjects, whom she refers to, cribbing from the United States Constitution, as “We the People.” Her tens of thousands of followers believe she holds authority over everything from law enforcement to income taxes. But to extremism experts and former followers, Didulo is a dangerous cult leader and a con artist.

Local residents were wary. “I was fearful,” says Shauna Sehn, who lives on a farm just outside of Richmound, recalling the arrival of Didulo and a couple dozen of her close followers. “Who are all these crazy people?” Shortly thereafter, hundreds of people, including Sehn, from Richmound and surrounding towns, protested outside the school building, screaming for the group to leave and honking their horns for hours as they circled the property. They held signs with messages like “Royal decrees are lying disease” and “Your kingdom does not belong in our countryside.” The RCMP, based a forty-five-minute drive away in Leader, dispatched a special mobile detachment to keep the peace. The RCMP said the situation posed no immediate threat, but they were nonetheless prepared for something more serious. Some feared this could turn into Canada’s version of the Waco siege. Apart from brief sightings when she went in and out of her RV, Didulo remained unseen, while members of her group, acting as her security detail, circled the school grounds, which they’d roped off, taking videos of the protesters.

The RCMP said the situation posed no immediate threat, but they were nonetheless prepared for something more serious.

The protests did nothing to sway Didulo and her followers. They weren’t breaking any laws; they were on private land. They had, it turned out, been invited to live in the old school by the man who had purchased the building and the property from the town after the school closed. Through last fall and winter, however, tensions only escalated between the townspeople and Didulo’s group. Cease and desist letters and emails, with threats of “public execution” targeting Richmound’s mayor and other locals if they didn’t leave the group alone, began to circulate. Though the letters were unsigned, it was clear to the people in town that Didulo, or her followers, was responsible. The RCMP, unable to determine an immediate threat, investigated but did not lay charges.

Now, after more than nine months, Didulo and her followers are further entrenched in Richmound. In such a short time, the presence of the group has exposed the fragility of a community confronted with an extremist ideology at its door. Some locals want Didulo and her followers out, worried that their town is being used to broadcast some of the most far-fetched conspiracy theories. Others, though they may not agree with Didulo, say the group should be left alone if they aren’t directly harming anyone. And a small but impassioned few, however, identify or sympathize with Didulo’s perspectives—including some who see the group’s presence in their backyard as an opportunity.

Little is known about Romana Didulo’s early life: we know that, as a teenager, around 1990, she immigrated from the Philippines to British Columbia. We know that she later ran a recruiting firm for the oil and gas sector. She had no public profile to speak of until the end of 2020, when she founded a political party, with herself as leader. The Canada 1st Party borrowed language from the American Republican Party—“draining the swamp in Ottawa!” and the like. Didulo’s platform was a vague combination of cutting taxes and prosecuting corrupt politicians and law enforcement agents, as well as eliminating “globalists and Communists” and targeting human and child traffickers—obsessions of the far right.

Over time, Didulo revealed increasingly strange aspects of her ideology: she claims to have received recognition from Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump—and that she has communed with aliens. She claims to be “a divine being sent to Earth to fulfill a spiritual mission,” wrote Christine Sarteschi, a professor of social work and criminology at Chatham University in Pennsylvania who has followed Didulo since 2021, in the International Journal of Coercion, Abuse, and Manipulation. “Didulo’s purported divine abilities are numerous. She can cloak and uncloak herself. She can freeze or erase the memories of other people. As an individual with the ‘highest frequencies,’ shape-shifting is one of her natural abilities, giving Didulo the capacity to become anyone or anything, at any time.”

Didulo’s rise coincided with multiple social and political friction points in late 2020. Countries, including Canada, had ordered their first doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Joe Biden was elected US president, sparking Donald Trump to falsely claim the election had been rigged. And the originator of the QAnon conspiracy movement had suddenly gone dark after years of posting cryptic messages, or “Q drops,” on the websites 4chan and 8kun, formerly known as 8chan. Popular QAnon influencers quickly offered their support to Didulo. “Didulo stepped into the power vacuum. In a matter of months, her popularity exploded,” Mack Lamoureux, who has covered Didulo extensively, wrote for Vice.

Conspiracy theories like the ones she spreads might be easily disregarded, but they have real-world consequences, can turn from nebulous ramblings and diffuse online speculation to dangerous, threatening, and personal manifestations in a heartbeat. In the lead-up to the 2016 US presidential election, false theories circulated about a connection between Hillary Clinton, her campaign chair John Podesta, and child slavery—leading to a QAnon follower entering a Washington, DC, pizza restaurant with a military-style rifle and a handgun, and firing several rounds, to investigate. In the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were countless people who died from the disease after deciding not to get vaccinated because of conspiracy theories that the vaccines altered one’s DNA or led to infertility. And when Trump lost the 2020 election, his theories about voter fraud and an election conspiracy sparked a mob of his supporters to storm the US Capitol building on January 6, 2021, to halt the certification of the election results. Three weeks after January 6, Didulo abandoned her nascent political aspirations and took to the messaging app Telegram, reportedly from her basement apartment in Victoria, BC, to crown herself Queen of Canada, commander-in-chief and head of the “Kingdom of Canada.” She claimed to have been appointed to these titles by the “same group of people who would have helped President Trump.”

By the spring of 2021, Didulo’s Telegram following had grown to 20,000 people—an audience for her speeches, announcements, and made-up decrees, including that Canada was pulling out of the United Nations and the World Health Organization and terminating all foreign aid. Didulo warned her followers against getting the COVID-19 vaccine, falsely claiming it to be a tool of genocide, and began threatening health care workers and people enforcing pandemic restrictions and vaccine distribution, saying they were committing “crimes against humanity.” Didulo flooded her Telegram channel with news articles critical of pandemic restrictions and denounced Canadian politicians as “Criminals and Traitors.” Through that summer, she threw her support behind so-called “freedom rallies”—protests across Canada against pandemic lockdowns and mask and vaccine mandates. In July, as Canada’s vaccine rollout was under way, she claimed to have begun distributing medical beds, nicknamed “medbeds”—non-existent technology that Didulo and others claimed can cure medical ailments, perform surgeries, cure cancer, and make people immortal. “I’m disabled with Multiple sclerosis,” one Didulo follower wrote on Telegram. “And I know med beds will take care of that.”

Through the fall, Didulo’s threats against government and health care workers became more violent: she urged her followers to prepare to attack anyone overseeing COVID-19 vaccine administration. “Shoot to kill anyone who tries to inject Children . . . with Coronavirus19 vaccines/ bioweapons or any other Vaccines,” Didulo wrote on Telegram, where her followers had grown to more than 70,000, according to the Canadian Anti-Hate Network. Those threats caught the attention of the RCMP, leading officers to detain her in November under BC’s Mental Health Act. The RCMP did not confirm details of her arrest to media at the time and no charges were laid, but Didulo posted a video after her release recounting how she was questioned by doctors and was deemed not “certifiable.” The moment solidified her base. When she declared that all debts in Canada—including credit card debt, student loans, and mortgages—would be forgiven, some of her supporters believed it to be true and subsequently lost their homes or have been penalized for not paying income taxes and other owings. Instead, many gave her their financial backing. Buoyed by the adoration online, in early 2022, Didulo hit the road, on a royal tour of sorts across Canada.

Near the end of January 2022, Didulo and a few close followers drove more than 4,000 kilometres, from Victoria to Ottawa, in RVs and other vehicles in order to join the so-called “Freedom Convoy”—a series of rallies and blockades—protesting COVID-19 vaccine mandates and lockdowns. Within a few days of trucks blockading parts of downtown Ottawa, which brought the eyes of the world to the capital for more than a month and prompted the federal government to invoke the Emergencies Act for the first time, Pierre Poilievre, months from being elected leader of the federal Conservative Party, expressed support for the convoy: “I’m proud of the truckers and I stand with them,” he said in an interview. “Canadians have finally had it.”

Didulo stepped into the spotlight, seeing an opportunity to use the attention of the protest to help grow her movement. “I am backed by the armed forces of the United States,” she shouted into a megaphone while standing on Parliament Hill. “There are no more elections, no more politicians, no more politics in the Kingdom of Canada.” She stated that “marshal [sic] law” would be in effect until she said otherwise. She also booked hotel rooms for Putin and then Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson, “either because they believed those persons would be arriving to meet with Didulo,” wrote Sarteschi, “or, more plausibly, to project the appearance of importance.”

A kind of madness has washed over the town, with people who otherwise led quiet lives being brought to the edge.

After the Ottawa protest dispersed, she and her inner circle left the capital to drift around Ontario, Quebec (including failed attempts to cross into the US), and Atlantic Canada, through the summer of 2023, looking for a place to land. In Peterborough, Ontario, where several of Didulo’s followers enacted her orders to conduct “citizen arrests” of police officers for “COVID crimes,” at least six people were arrested and charged with assaulting police. The group tried Halifax, and then the small town of Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia, before turning west.

One night last September, Didulo and her convoy pulled into Kamsack, Saskatchewan, a town of under 2,000 people near the Manitoba border. The town’s fire chief, Ken Thompson, told the CBC that he overheard Didulo’s group telling locals they were going to educate them and impose changes. Though Didulo reportedly never exited her RV, her followers riled up locals. As tensions rose, Kamsack’s community safety officer called the RCMP, and the mayor, Nancy Brunt, arrived on scene. Didulo’s security team questioned Brunt’s mayoral authority, Brunt said, telling her that “God had given them this land.” Brunt retorted: “This is my town. I’m in charge.” Kamsack officials organized a meeting and invited Didulo. The local hospital locked its doors and increased security over fears that Didulo or her followers might cause violence. But before the town hall could begin, Kamsack residents gathered in protest; Didulo and her entourage left, escorted out of town by the RCMP. “We’re so grateful for what everyone did yesterday,” Brunt told reporters, “coming together, all on the same side, all saying, ‘This is our town and no one is going to take it away from us.’”

After more than a year on the road, Didulo’s convoy continued west, in search of a more welcome place to land.

There are around sixty-five homes in Richmound, in half a square kilometre, so people are close. For decades, the Saskatchewan town was defined by its camaraderie and relative peace. Students attended one school from kindergarten through grade twelve, and families would gather at the park or the community centre. The curling club and baseball diamonds were packed on weekends. One of the annual highlights was the New Year dance. Richmound’s financial prosperity was tied to agriculture and the oil and gas industry; one of its peaks was in the 1980s, when natural gas was discovered below the town. New businesses and housing sprung up, and young people flocked to live there; the North Canadian Oils company drilled non-stop. But things began to decline in the 2000s—slowing oil and gas activity and resultant job losses—culminating around 2008, when the school closed due to a dwindling student population. “Some families moved away immediately,” says Sehn, who taught at the school for twenty-three years. In the years that followed, the grocery store shuttered, so did the curling rink.

The school eventually fell into the hands of Rick Manz, a local handyman who, in 2017, purchased from the town the building and the land it sat on. According to Richmound mayor Brad Miller, Manz had wanted to turn the set-up into a medical cannabis operation, but that plan had fallen through, and the property lay vacant for years. (Manz did not respond to interview requests.) Miller says Manz was falling behind on paying property taxes, amounting to around $1,200, on the school. “He thought that he didn’t have to pay taxes, but everybody has to pay them,” Miller told me. Manz’s tax woes may have prompted him to reach out to Didulo’s group, which had been in the news. He had also garnered a reputation in town for peddling conspiracy theories: neighbours recall Manz spouting anti-vaccine falsehoods, claims the COVID-19 pandemic was a hoax, and more sensational QAnon theories—so it’s possible he also identified with some of Didulo’s views. Jody Smith, Manz’s neighbour, says he doesn’t know how exactly Manz got in touch with Didulo or her followers to invite them to occupy the old school—but that Manz warned him a couple days before the group’s arrival. “‘Things are gonna change,’” Smith recalls Manz saying to him last September.

After Didulo and her followers arrived, the group took a defensive posture that many perceived as hostile: erecting a metal fence around the school, installing “No Trespassing” signs, and scraping the school’s slogan—“Richmound School, with a you in it”—off the building’s sign. A couple weeks after Didulo’s arrival, as protests unfolded in town, Manz was charged with assault after an altercation with a neighbour who approached the school property one Sunday afternoon. (Manz’s trial has been adjourned until November.*) Almost overnight, many parents no longer felt safe bringing their children to the playground next to the school, partly alarmed about Didulo’s followers filming them without consent. Residents have been overcome with a fear they never expected when growing up in, or moving to, such a quaint place. “I hate that this cult in our village is now a deterrent for me,” Sehn says. For the first time, she’s thought of moving away. “And that breaks my heart.”

Word in town is that Didulo has plans to repaint the school purple and gold, her royal colours.

Anger and frustration in town have been boiling ever since: one person threatened to burn the school down with everyone inside it. A kind of madness has washed over the town, with people who otherwise led quiet lives being brought to the edge. One person told me they’d endure physical violence, even take a bullet if necessary, in order for the RCMP to lay charges against Didulo or her followers. These threats, and others like them, sincere or bluster, have shocked some residents. “You give [Didulo’s group] the power to make you afraid. They haven’t done anything,” Smith says, suggesting the town was giving Didulo too much oxygen, giving credence to something that loses its power when ignored. “She can make a decree, but does it have an effect on me?”

A rift grew between the locals who were vehemently opposed to the group and those who were seemingly sympathetic toward them and got caught up in the hysteria. “The perception among the townsfolk here is if you didn’t participate in the merry-go-round horn honking protest, then you must be associated with the [group],” resident Hugh Everding told me. He became so alarmed by locals who have tried to eject the group that he changed his profile description on Facebook to “Living in Richmound SK where the locals are crazier than the ‘cult.’”

Some residents became obsessed with watching the Kingdom of Canada’s daily livestreams, keeping their eyes and ears peeled for any whiff of wrongdoing they could use against the group. Last November, someone thought they had spotted a smoking gun: a heater propped up on a propane tank inside the school, a blatant fire code violation. Mayor Miller sent the fire chief, a building inspector, and a bylaw officer to the school, but neither Manz nor the group would let them in. Miller hired a lawyer to apply for a warrant to enter the school, in the hope that it would, if granted, allow them to pursue bylaw infractions and ultimately force the group out. “If you feel unsafe with people in your town, you should be able to do something,” Miller says.

Didulo and her crew fled to a farm, about fifteen kilometres away, that belonged to Tom Tuchsherer, Richmound’s previous mayor until he stepped down in 2019. Tuchsherer says he doesn’t believe in Didulo’s ideology but had been ashamed of how locals were getting so riled up. When Manz called him to ask if Didulo’s group could park their vehicles on his land for a few days, Tuchsherer was visiting his dying wife in the hospital. “I said yeah, whatever,” he recalls. “I had no issue with it.” His decision was met with scorn. Tuchsherer said his family received threats on social media, and he was accused of having lost his mind. Tuchsherer says that the night after Didulo and her followers arrived, neighbours drove pickup trucks around his property, firing flare guns to scare the group.

Smith and his wife were there too, using one of Tuchsherer’s workshops. “They were really unhappy that [Didulo] was there,” Smith says. “I didn’t want them burning anything down thinking that was going to drive them out.” For Smith, that incident revealed how volatile the situation had become. He calls what the group has done “disrespectful” and says that “they crossed a line,” but in his mind, Didulo’s presence was revealing something else entirely in the town of Richmound. “There’s lots of good locals here,” he says, “but there’s a few that are just to the extreme—and even among them there’s extreme ones. Who knows what they’re capable of.”

Two years before Didulo arrived in Richmound, around the time she and her followers were trying to spread their message across eastern Canada, Melinda Fischer moved to Richmound from Alberta. Fischer owned a third-generation farm in the Richmound area with her sister and moved back in the hope of returning to a slower pace of life. “Boy, was I in for a rude awakening,” recalls Fischer, who had retired from a job at Scotiabank and begun working as a bus driver. Shortly after moving into a bungalow in town, she decided she wanted to build a chain-link fence around her property. She hired Rick Manz to build it. For Fischer, Manz’s beliefs were just some of his many quirks.

When she noticed water damage on the public road that might affect her fence, she notified the town council. According to Fischer, Mayor Miller and the council told her they would pay for repairs after they fixed the road issue. Fischer hired Manz to dig holes for the fence. But when she presented the council with a bill of $630 in the spring of 2022, the town offered to pay only half. Fischer felt duped—enough that she began questioning the town’s finances and eventually embarked on a crusade to expose what she believed to be a financially irresponsible town council led by a mayor who, she believes, is misusing taxpayer funds. Fischer started airing her grievances on Facebook, publishing minutes from town council meetings that, she argued, proved the town’s misspending. “I opened up a big can of worms, because nobody ever questioned or stood up to them,” Fischer says. Even though the town eventually ended up paying the entirety of Fischer’s bill for the fence, she remained hell-bent on exposing what she describes as “corrupt bylaws and policies”—and removing the mayor.

Over the years, Fischer’s disdain for the mayor and the town council festered. She made a spreadsheet documenting any town expenses she could find and became alarmed at rising expenditures. “There were two years, one went up to $61,000 and the other one went up to $71,000,” she says. “People, wake up, this is our money that they’re spending. . . . I’m sort of flapping at the gums, like, I’m a financial adviser. Look!”

Fischer’s hatred toward the town administration continued to grow as she tallied up its expenditures. She was furious over the hiring of a full-time caretaker, a position she believed should have been on a contract basis. “[We are] wasting our money when our village is already going broke,” Fischer says. Then Didulo rolled into town last fall. At first, Fischer says, she was disinterested in the group—she had never heard of them. “How can you just be the Queen of Canada? I just brushed it off,” Fischer recalls. “I just don’t really know what QAnon is all about.” But after a few months, as most of the town rallied to kick the group out, Fischer had an idea: a sudden influx of a dozen people, around 10 percent of the town, could help her cause. She became convinced that a bunch of potential new votes could help oust Mayor Miller. But Didulo and her followers weren’t residents; they couldn’t vote in the upcoming municipal election. In a vacant lot that Fischer owned, right near the old school, lay the solution.

Fischer asked Darlene Ondi, Didulo’s right-hand woman, for the names of everyone living inside the old school. Fischer added Didulo, Ondi, and ten others to the title of her vacant lot. Now, as landowners, they would be residents with a vote. She then emailed the updated title information to Richmound’s administrator. “I kinda did it out of spite,” Fischer told me. “It was my total idea. I thought, ‘You know what would really piss these people off . . . ? I’m going to give [Didulo’s group] free rein to the city.’” Word quickly spread through town—without knowledge at the time that Fischer was behind it—which confirmed the worst fear of many locals: that Didulo and her group were making moves to take over the town.

In March, Fischer and Manz appeared together for the first time on Didulo’s Telegram livestream. Ondi applauded them for their “bravery.” “It is not a comfortable nor sometimes appreciated position, and it isn’t easy to stand out above the crowd,” Ondi said, acknowledging that she had become a landowner in Richmound.

“Land owners, voters, eligible to walk around freely in this town without supposedly being harassed,” Fischer replied with a smile.

“That’s great for the world to know,” Ondi said. “Twelve new voters, maybe more.”

Eventually, Fischer raised her ongoing issues with the town, referencing her spreadsheet that documented the council’s spending. She mentioned various municipal expenses: the $900 a month spent on someone to test the safety of the town’s water—who, she noted, is married to a Richmound elected official, as if a conspiracy is afoot; the $14,141 the town has paid in legal fees over Didulo’s presence. “I, for one, a resident of Richmound, don’t want to pay it,” Fischer said. “I want you to know this, too,” she continued, as if speaking to her town, “I have stuck up for you as an outsider. I am an outsider, according to these people in Richmound. . . . With an objective point of view, to those on the opposite side of the fence, there shouldn’t be any opposite sides of the fence.”

While Fischer insists she’s not a member of Didulo’s group—“I know I have to pay my taxes,” she told me—she has nonetheless been embraced by them. Later in March, Didulo hosted a livestream in which she bestowed “ministerial titles” on her most dedicated followers. In her fantasy cabinet, Manz was named “Minister of the Economic Corridor” and Fischer was appointed “Minister of International and Internal Protocol.”

Over the following month, tensions only escalated in town. One night, several locals, dressed up in clown suits and masks, held up a mock version of Didulo’s purple Kingdom of Canada flag and filmed themselves lighting it on fire. One woman drove up to the fence around the school in the middle of the night and screamed obscenities at the building. Someone who had set up a fake Facebook profile began messaging Fischer, writing: “You have more eyes on you and enemies than you can ever see. You are done!!”

Mayor Miller has tried to restore calm, hosting closed-door meetings overseen by a facilitator in an attempt to resolve issues—some that predate Didulo’s arrival. Fischer was not part of the meetings. “I was proud of a couple people that showed up and talked with the group in a positive manner on our side,” Miller says.

At the end of April, a group of Richmound locals anonymously launched a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for the town’s legal fees to shore up municipal bylaws and “any necessary measures to expedite Romana’s removal and manage this unprecedented situation,” the page states. The town had, until that point, spent around $20,000 in legal fees on the issue. Miller told me that while the town council is not, and cannot be, involved in any such fundraising efforts, the council’s lawyer advised him that it “can accept any donations it wants.”

Word in town is that Didulo has plans to repaint the school purple and gold, her royal colours. Her followers have been seen to be tilling the land around the school in order to plant gardens or farm. Richmound’s mayoral and council election is in November.

This March, I visited Didulo’s compound and walked the fenced perimeter. Her RV, parked outside the school, was adorned with a “MEET AND GREET” sign. The building’s windows were boarded up; no one was in sight. I shouted “Hello!” and, after a minute or so, a man emerged and asked if he could help me. I introduced myself as a journalist, but before I could finish my sentence, he waved me away, saying they wouldn’t do interviews. By this point, another man had walked out and appeared to be filming me with his phone. “When’s Romana’s meet and greet?” I asked. He mumbled something inaudible, then said I could check their website. The man urged me to be more “respectful” with Didulo’s name, ostensibly imploring me to use her royal titles, then returned inside.

The fence that surrounded the school appeared to have no opening at all, no easy way for people, or anything, to move in or out. Despite being made of metal, parts of the fence appeared flimsy, as though anyone could just push it all over.

*Update, June 6, 2024: The article has been updated to reflect the latest developments in Rick Manz’s court proceedings.