ENVIRONMENT / MAY 2025

A Canadian Company Says It’s Fighting Pollution in the Philippines. Is It Cashing In Instead?

Paying plastic-waste pickers might just be a licence to pollute

BY RÉMY BOURDILLON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LISA MARIE DAVID

Published 6:30, APRIL 8, 2025

HERMINIO AGUILAR hasn’t had an easy life. Now seventy-three, he spent years digging irrigation wells on his native island of Negros in the Philippines, a few hundred kilometres south of Manila. In 2006, he had a stroke, which forced him to limit his activities. “I needed recovery,” says Aguilar, who is widely known as Toto. He went to live with his sister in Quiapo, a lower-income district in Manila, where some of the Spanish colonial houses are falling into ruin and children play pool on makeshift tables.

There, he accepted a position as a street sweeper. To earn extra money, he began collecting polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, plastic bottles—the kind used for water and sodas—that he found along his route. He would sell them to MSTS Junkshop, a small family business, which is packed to the ceiling with sacks of metal, cardboard, and plastic. Such stores play an essential role in the local waste management system: they purchase recyclables from waste pickers and then supply recycling companies with clean, sorted materials.

Across the Philippines, waste pickers—an informal community that at times relies on child labour—are typically more motivated to collect glass and metal. At MSTS Junkshop, a kilogram of aluminum fetches up to seventy pesos, or $1.72, compared to just fourteen pesos ($0.34) for PET. But one day in 2019, the family that owns and runs MSTS made Toto an offer: he could register as a member of a company called Plastic Bank. For every kilogram of plastic he collected, Plastic Bank would pay him a premium—on top of what he received from the junk shop.

Based in Canada, Plastic Bank issues what are known as plastic credits, starting from $0.16 per kilogram. In theory, this program allows clients like local PepsiCo and Coca-Cola manufacturers to offset their plastic waste by financing plastic collection in any of the countries where Plastic Bank operates—which, in addition to the Philippines, includes Indonesia, Thailand, Cameroon, Egypt, and Brazil.

Plastic Bank uses blockchain technology to record how much material each member collects. Based on that data, its credits scheme has led to around 20,000 tons of plastic being collected in the Philippines over the past three years; it’s also raised the income of over 20,000 members in the Philippines by 20 to 35 percent. Waste collectors receive occasional gifts depending on their output, such as vouchers to buy canned goods from partner stores and five kilograms of rice at Christmas. Partner junk shops benefit from the added volume of plastic that they sell, but Plastic Bank also provides them with sacks in which to pack the plastic, and it sometimes offers financial assistance for expansion.

Tricia May Vargas, a manager at MSTS, says she’s seeing more plastic come into the junk shop. “I would say that plastic used to occupy half their truck,” she says, referring to services that pick up materials and deliver them to recycling facilities. “Now they can fill the entire truck [with] just plastic.”

The concept of plastic credits emerged only a few years ago but is gaining popularity. A 2024 report from the World Bank identified 160 plastic crediting projects registered globally as of December 2023. Such initiatives aim to tackle worsening plastic pollution around the world: it’s estimated that at least 8 million tons of plastic is dumped into the oceans each year, and this figure could nearly triple by 2040 if current trends continue. Microplastics have infiltrated the entire food chain, from plankton to the human body, with still-unknown effects on animal and human health.

According to various studies, the Philippines is one of the world’s largest contributors of mismanaged plastic waste into the oceans. Filipinos use much less plastic on average than individuals in wealthier countries—about twenty kilograms per capita annually as opposed to, by one estimate, 105 kilograms in Canada. But in most neighbourhoods, waste is not sorted; it’s mixed together in garbage trucks and stored in poorly managed landfills. (The Philippines, unlike Canada and other countries, does not export its trash.) Many products, from shampoo to coffee, are sold in single-use, multi-layer sachets, which are almost impossible to recycle and have no resale value. According to the World Wildlife Fund, nearly three quarters of the volume of plastic that spills into the ocean from the Philippines comes from open landfills located near vulnerable waterways.

Plastic Bank CEO David Katz started the company in 2013 with the stated goal of alleviating poverty in places where trash is abundant and stopping the flow of plastic into the ocean. He grew up on Vancouver Island and says he has witnessed increasing amounts of plastic on the coast over the years as well as during his travels—which made him concerned about the effects on birds and marine animals. “Part of me is speaking for life that doesn’t have a voice,” he says with the passionate tone of someone giving a TED Talk.

Since 2022, companies in the Philippines are required by law to recover a portion of their “plastic product footprint” (up to 80 percent by 2028); one way to do so is by buying plastic credits. But there is no universal standard for managing and regulating plastic credits, making it difficult to measure the industry’s impact. As Katz puts it, “It still seems like the Wild West.”

In particular, plastic credits schemes tend to overlook the fact that there are hundreds of types of plastic, says Neil Tangri, a science and policy director at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, or GAIA, a non-governmental organization that describes itself as working toward climate and environmental justice. “Cleaning up a ton of plastic in the Philippines is not the same as producing a ton of a different plastic somewhere else in the world.”

While various players in the industry all handle easy-to-recycle plastics like PET bottles, they have yet to find a solution for single-use sachets. Plastic Bank advocates for a ban on non-recyclable materials; its member pickers tend to leave sachets in the street. PCX Markets, a leading plastic credits organization operating in the Philippines, acknowledges that such packaging gives poorer communities access to fast-moving consumer goods. The company, now based in Singapore, organizes the collection of sachets and primarily sends them to cement kilns to be used as fuel instead of coal, a process that’s highly controversial because it can emit toxic pollutants into the air.

Buying plastic credits also doesn’t “address the problem at source,” says Marian Ledesma, a campaigner focused on zero waste—a movement to eliminate trash—at Greenpeace Philippines. “For corporations, it is a way to continue producing more plastics, because they’ll always be able to buy more credits to offset this.”

Are plastic credits a licence to pollute? “You know what? Kinda,” Katz admits after brief hesitation. However, he prefers to frame them as a type of incentive for companies to reduce their consumption of virgin plastic. “I believe that the plastic credits should be even more expensive,” he says. “We need to really create an incentive for people to use more recycled content.”

But Tangri is not convinced by that logic: “Look at what’s happening with carbon credits. When their price goes up, two things happen: a lot more actors enter the market—which will bring down the price—or the polluting companies put pressure on governments to reduce the requirements.”

Comparisons with carbon credits, which are increasingly questioned for their effectiveness, are inevitable. To have any real value, both carbon and plastic credits must demonstrate what’s known as additionality, meaning they need to result in action that would not have occurred in their absence. Komal Sinha, senior director for plastic policy at Verra, an American nonprofit that issues both plastic and carbon credits, believes it’s easier to measure the impact of plastic credits, “because plastic is a visible, tangible material.” (A January 2023 investigation in the Guardian accused Verra of issuing “phantom credits”—credits that don’t represent significant carbon reductions—a claim the company denies.) In Plastic Bank’s case, says Katz, “we’re trying to add on more collectors. I think every collector ultimately creates some additionality.”

At United Nations talks late last year, delegates from more than 170 countries (as well as industry lobbyists and the International Alliance of Waste Pickers, which represents workers who make a living from collecting recyclables) failed to agree on a global plastics treaty aimed at fighting pollution, mostly because of opposition from a group of oil-producing countries. Compared with globally coordinated actions, plastic-offsetting schemes may seem more immediately effective. But Tangri points out that they amount to only scattered projects and not a “comprehensive” system. This approach, he says, runs counter to more effective solutions.

In places like the Philippines, says Tangri, that includes building alternative economies that don’t rely on plastics. It can also mean untethering collectors’ wages from the prices set by plastic credits projects or simply paying them a salary. “The waste pickers involved in the [treaty] negotiations have been very clear. They’re not asking for these kinds of plastic credits,” says Tangri. “What they’re saying is: when we pick things up, pay us for the service—don’t make us dependent on the market price.” Though that wouldn’t solve everything, he says, it would mean collectors could simply pick up everything they find.

For its part, Plastic Bank isn’t interested in hiring full-time collectors. “I think it’s even more exciting for the world’s most resourceful to have an unlimited opportunity,” Katz says. “If they want to work more, they’ll work more. They are the masters of their lives.”

In Quiapo, the overwhelming amount of trash on the sidewalks makes the work nearly invisible. Bottles and sachets pile up on the white-sand beaches of remote Philippine islands, where operating a junk shop is hardly viable due to the high costs of shipping materials to the nearest recycling plant, according to Mother Earth Foundation, a zero-waste NGO.

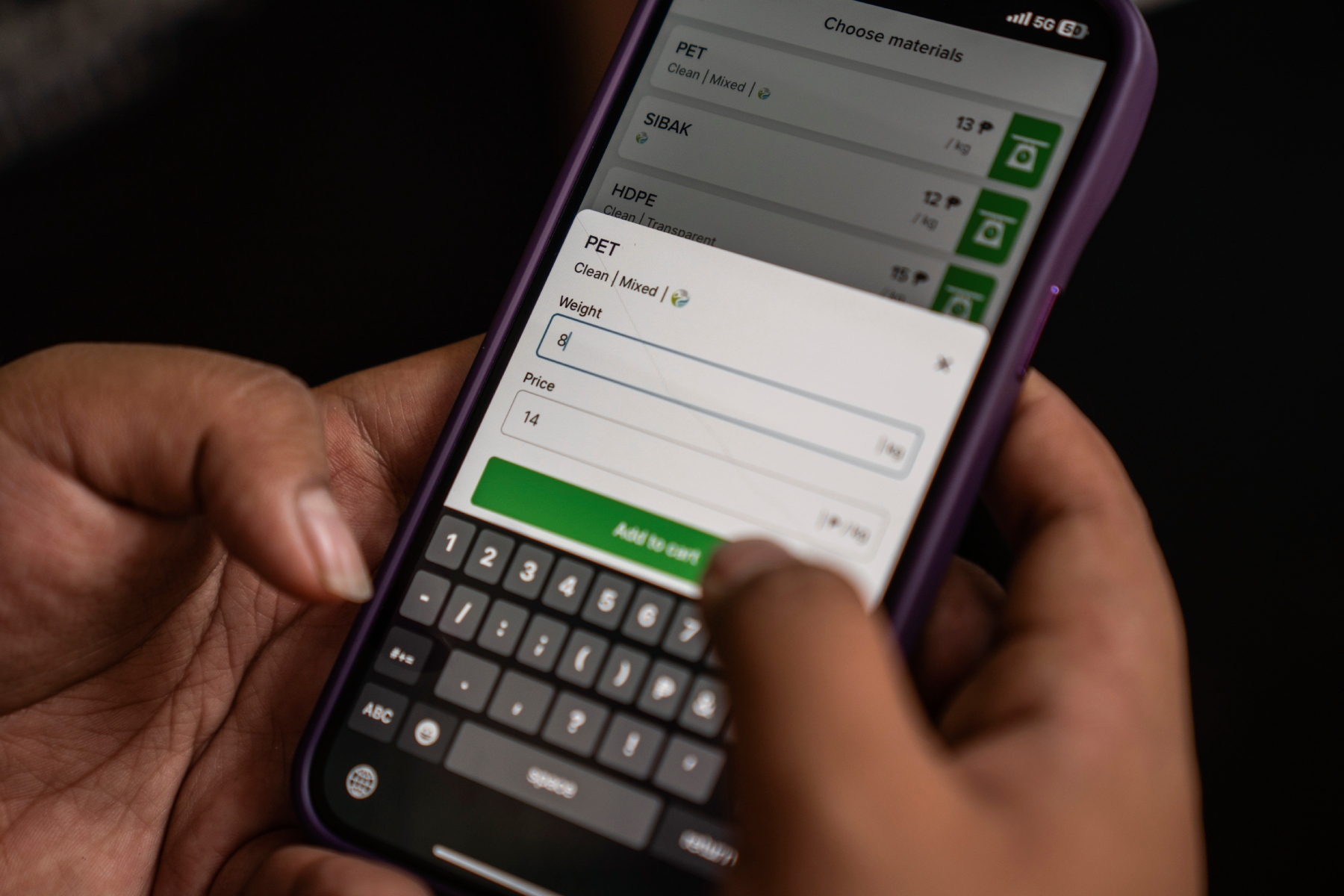

During typhoon-induced floods in 2023, Toto contracted leptospirosis, a bacterial infection that affected his right leg. Though he’s still working, he has difficulty walking, which is also in part due to his age. “We have a big garbage can. So, my neighbours go there, throw their trash. I go through it and sell what’s possible,” he says. He now goes to the junk shop almost every day. There, a manager helps him use the Plastic Bank app to record the weight of PET he’s collected. Based on his entries, the app rewards him with tokens that he can later convert into cash and deposit into a digital wallet, a widespread payment mode in East and Southeast Asia. Through his income from the junk shop and the bonus from Plastic Bank, he earns about 100 pesos a day, or about $2.42, which is not nearly enough to live on (the minimum wage is currently 645 pesos for most sectors in Metro Manila). He still lives with his sister and helps out with chores.

Toto smiles constantly. Even though what he’s doing is seen as dirty work, he’s proud of what he does. “As waste collectors, we get respect,” he says, “because we still earn money.”