It’s 3 p.m. on a Saturday, and despite a few missed turns and several kilometres of backtracking, I’m the first to arrive at a debate prep session for Toban Leckie, thirty-year-old political tyro with the upstart Strength in Democracy party. I let myself in to his parents’ cottage on Picard Lake, about 150 kilometres northeast of Toronto, in the riding of Peterborough–Kawartha. There’s a pair of Toban Leckie lawn signs in the foyer to match the two I saw on the drive up (part of a limited campaign arsenal), and the radio is blaring the CBC. After twenty minutes spent staring outside at the coruscating water, I awkwardly welcome Leckie’s campaign team, and then Leckie himself, to the most tranquil war room in Canada.

Things get less tranquil, however, as Leckie recounts exchanges from a recent debate. “I want to be Peterborough’s voice in Ottawa, not Ottawa’s voice in Peterborough,” he says. It’s a statement Leckie has made before. But when he says it this time, a clamour breaks out: “That’s what he said? What!” says one team member. “That’s what we’ve been—that was in our brochure!” stammers another, who’s also Leckie’s close friend and campaign manager.

It seems NDP rival and veteran politician Dave Nickle lifted the line for himself. Leckie smiles as he tells his team of five (six, if you include his girlfriend) about the incident, looking almost gratified that one of the Big Three would copy his party’s mantra. When opponents take up Strength in Democracy’s positions, he says, “that demonstrates we’re affecting the dialogue.” For Leckie, a self-employed contractor and a graduate student at Trent University with no political experience, it’s about the best he can hope for.

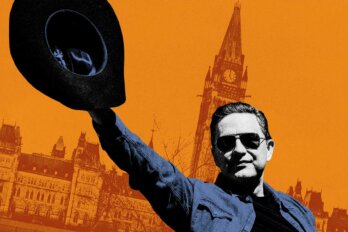

Peterborough–Kawartha is a Conservative stronghold whose most recent member of Parliament, Dean Del Mastro, resigned last year after he was convicted on three counts of breaking the Elections Act. That means Leckie is effectively, if not technically, standing in a by-election; and with his candidacy announcement in June, he became the first member of Strength in Democracy to contest a riding outside Quebec. The party was founded last October as Forces et Démocratie by two sitting MPs—Jean-François Larose, formerly of the NDP; and Jean-François Fortin, the current leader, who defected from the Bloc Québécois—making it a fringe group with as many seats as the Green Party. It was after Leckie joined that the party was impelled to adopt an English name, proposed by the candidate himself. (Because the writ dropped before the anglicized moniker could be made official, only the original name will appear on the ballot—not ideal in a riding where the percentage of people who speak French can be comfortably rounded to zero.)

A self-described regionalist party despite its Blackshirtish name (which Leckie says voters haven’t taken issue with), Strength in Democracy takes few hard policy stances, all of which place it on the left side of the spectrum: It’s against oil sands and pipelines but in favour of Senate reform. It wants to restore funding to the CBC and keep Canada’s military away from ISIS. But for the most part, it’s up to individual candidates and MPs to decide what they believe is best for their constituents. That means Leckie is permitted to wonder aloud during the session whether the retirement age should be lowered to sixty-five, or to declare with impunity that he’s not always certain about what he believes. And as the debate prep carries on, as the sun makes a silhouette of the trees and Leckie demands to know why the hell parties are making policy decisions just to win votes, it becomes clear that while he’s learning how to argue like a politician, he may never be able to act like one.

Having participated in only a few debates so far, Leckie is still figuring it all out. This is his first formal prep session, but the discussion meanders around his rhetorical strengths and weaknesses, peppered with sometimes vague suggestions (“tackle an issue and say how this party is different”) and Pollyanaish boosterism (“I think you won that last debate, I honestly do”) from the team. It seems unfollowable and unproductive, but Leckie takes copious notes anyway, insisting that it’s all very helpful.

Leckie is passionate about politics—possessed of all the idealism that the clichéd adjective implies, and of all the earnestness that loses elections. (His campaigners are afflicted with this same earnestness: When the group broke after an hour and a half of shoptalk, one asked me unironically if I could imagine anything more fun. I didn’t have the heart to say that I could and, in fact, frequently had been.) He tells me that he listened to the Maclean’s leaders’ debate on speakerphone, sitting on the floor of a client’s heatless nineteenth-century cabin, eating dinner and yelling at Stephen Harper’s disembodied voice through mouthfuls of food. He tells me freely that his chances of winning Peterborough–Kawartha are slim, but that he’s happy just to be part of the conversation. Still, he’s not sure whether he can call himself a politician just yet. “Not that elected office is necessary,” he says. “But I’m acting like a politician.”

As the night wears on, the action moves from the solarium to the living room, where the team listens to one of Leckie’s debates in the same way hockey players review video. His voice quavers as he fields the first question, and again when he tells the audience that he doesn’t know if free-trade agreements can be repealed because he’s “not a politician yet.” When the moderator informs the debaters that they can make closing statements in whatever way they choose, Leckie tells the audience he feels tempted to sing, but the joke doesn’t take. Yet it’s clear throughout the debate that Leckie knows his riding well, and that, unlike his competition, he can speak without consulting a policy binder.

Still, after hours of discussion, it doesn’t seem to me that Leckie has got the role of hardline politician down. He’s relentlessly reasonable. He doesn’t want to call Nickle out for pinching Strength in Democracy’s line—“I don’t want to make fools of anybody”—or to attack his opponents, or to be what Canadian politics is right now. When I ask if he’d ever consider running for one of the major parties, he doesn’t rule out the idea (surely not the response a campaign manager likes to hear). But for that to happen, he says, “it would require a major shift in one of them,” an unlikely turn away from the pettiness and tone-deafness they represent to so many Canadians.

It’s nearly 10 p.m. when the team gathers around the kitchen table for dinner, seizing burgers and sausages as if they’ve only just realized how hungry they are. When Leckie tells them to have at the beer and wine, one of the volunteers asks if she can make a Caesar instead. But while vodka abounds, there’s no Clamato. “Mistakes were made,” Leckie says. He’s never sounded more like a politician.