“The common image of the taxidermist has sunk from that of a civilized craftsman to that of an antisocial ghoul in the tradition of Norman Bates of the Hitchcock movie Psycho, who taxidermied his mother.”

Jane and Michael Stern, The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste

For someone who makes art from dead things, Mirmy Winn is unexpectedly sunny. There is nothing at all ghoulish or anti-social about her. When I met her at her Vancouver home, she wore a blue dress with a Tom and Jerry print and had her blond hair down. She told me that twice a year she performs with the ’70s-style dance troupe Tommy Noble and the Seahorse Dancers, and showed me her model train set, which included a tiny painted nudist, two hookers, and a beer-swilling clown. She laughed easily and smiled often—even when she brought me the human skull.

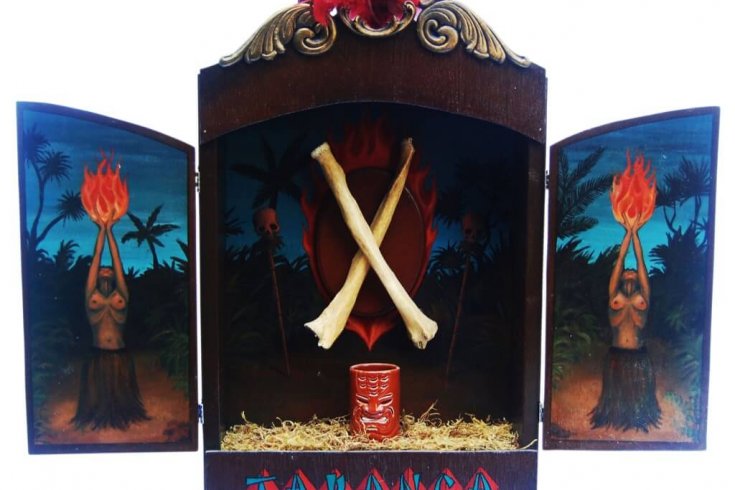

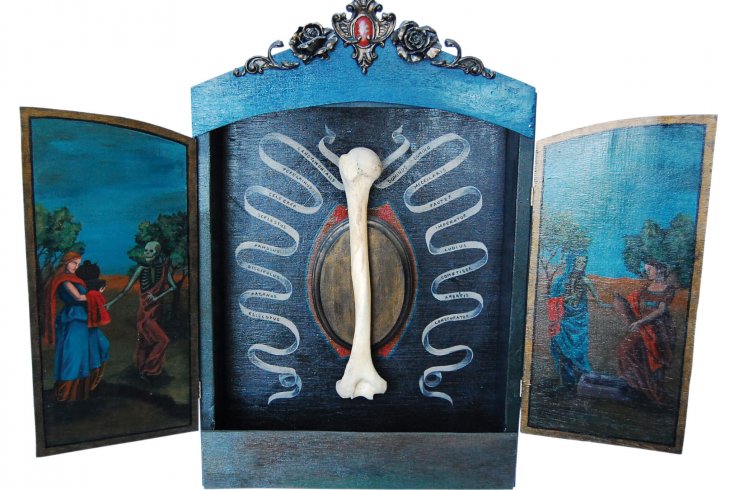

She didn’t place the skull in my hands. She grinned and made me reach for it—a kind of dare. The same morbid flirtation permeates her work, in which she builds and paints ornate boxes to house delicate remains like taxidermy pieces and animal skeletons. Some of her boxes remind me of marionette stages or grade school dioramas. The boxes that make up her Human Series, however, resemble medieval triptychs, with hinged side panels that open to reveal mounted human bones. Like her dare with the skull, Winn’s art challenges viewers to stand close to death. The pieces are memento mori: reminders that we, all of us, are going to die.

I took the skull from her and found it lighter than I’d expected, and a little rougher. It didn’t smell rotten, necessarily, but it did smell bad. After holding it for a little while, I could feel the smell, whatever it was, tickling the back of my throat. Winn nodded. “They all have that smell,” she said.

Winn grew up in Winnipeg. When she and her sister were children, their parents took them out on the Red River for painting trips: “My dad would spot a place, and we’d canoe there and eat food and paint all afternoon.” Her father was a lawyer, not an artist, but he knew enough to teach his daughters the basic elements of composition. Mirmy also loved to draw. The household rarely held enough paper to satisfy her voracious artistic needs, so her mother gave her the cardboard liners from pantyhose packages.

When Mirmy was in grade two, her school entered a province-wide drawing contest aimed at raising money to acquire a new snow leopard for the Assiniboine Park Zoo. “We had a snow leopard boy, and he needed a snow leopard wife,” she said. She saw a drawing of a snow leopard leaning on a cushion that one of the older students had made. She appropriated the idea—“My first art theft”—and drew a picture, in crayon, of a snow leopard sitting on a purple pillow in the forest. “It was ridiculous,” she admitted, but the piece won. First prize was a seat of honour in a parade, but Mirmy had to decline. “My father thought it was absolutely obscene,” she said. Still, after winning that contest she felt, for the first time, that she was an artist.

In truth, the young Mirmy was more interested in weasels than in snow leopards. She grew up fearing the one that stalked the forest bordering her family’s riverfront property. Weasels are mean. As a child, she was terrified of being attacked by them. “They are cute, but they actually kill things,” she said. “If you have weasels, you have no other wildlife.” Her fascination with the nasty little carnivores endured, and travelled with her to Vancouver, where, years later, she enrolled in the bachelor of education program at the University of British Columbia.

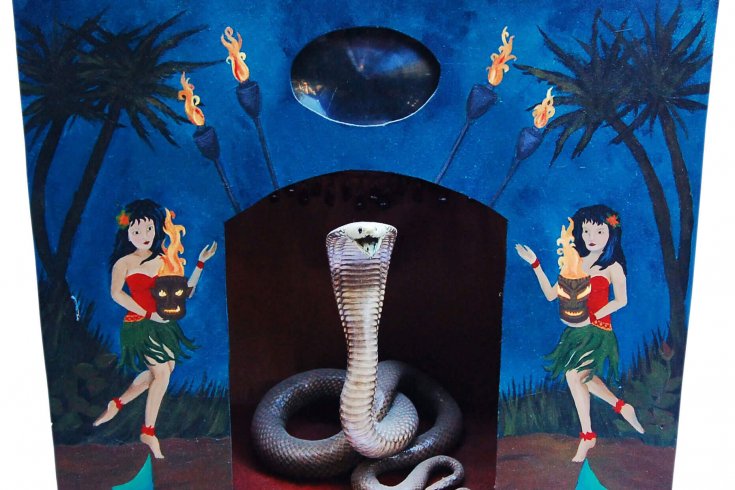

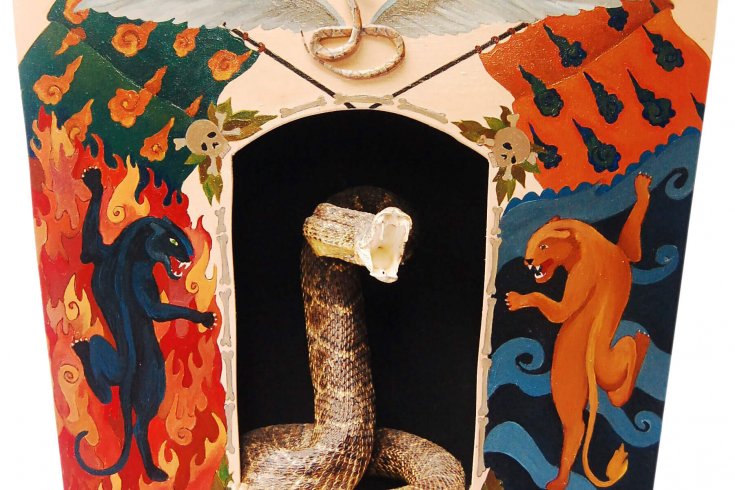

She bought her first stuffed weasel in 2003 and named him Mr. Sizzles. The weasel was not handsome; it was one of the most poorly mounted taxidermy pieces Winn had ever seen. One of his eyes was higher than the other. He had a gin blossom nose and crooked teeth, but Mr. Sizzles’ defects endeared him to Winn. She built a box, painted it, and placed him in the centre. The piece inaugurated her Weasel Boxes series. She purchased more vintage mounted weasels from thrift stores, and from taxidermists liquidating their collections. The more grisly and sloppy the mount, the better; she couldn’t resist an animal with one eye or a lopsided mouth. “The weasels with the funny faces are unloved and need a good home.” She built dioramas for all of them, placing each honoured critter in the centre, and painting the boxes with images inspired by everything from Japanese tattoos to ’50s pin-ups and the Mexican Day of the Dead.

The playfulness of each piece relieves whatever gloom an old, dead animal in a box might suggest. One of Winn’s weasels, named Mittens, is a master hypnotist. Pushing a button on the box causes Mittens to shout “Sleep!” with a rather unhypnotic tone and volume. The Nicknamer is a mounted pine marten that invites the viewer to select a twenty-four-hour nickname from a deck of fifty-two labelled cards. Options include Crybaby, Lumpy Pants, and Puddles. A piece entitled World of Hurt features a fortune-telling mink. Viewers are prompted to ask the mink a yes or no question, then push a button for the answer. Sadly, the digitized voice always says no.

Even the mink with the crystal ball could not have predicted the divided public reaction to Winn’s work. She first exhibited her weasel boxes in 2005, in a show called, appropriately, Weasels. Many gallery visitors loved the exhibit’s lowbrow quirkiness, and it broke the gallery’s sales record. But other people were horrified. They considered taxidermy tasteless at best, immoral at worst. It didn’t belong in an art gallery, they felt, but on rough tavern walls or above the fireplace mantels of redneck trophy hunters. “I haven’t sold my taxidermy to too many vegetarians,” Winn admitted. At one show, someone wrote all over the gallery guest book that she was a murderer, then stole two of the four weasels from their boxes. At another, a woman stomped into the gallery—“She was about sixty, with wild, woolly hair”—and hollered at Winn about the murderous and depraved art on display. “What have you done? ” she shrieked. Winn figured the woman was likely the thief from the previous show. She calmly explained to her that the taxidermy in the show was all vintage: “It’s not like I went out in my Elmer Fudd outfit and hunted weasels.” The woman eventually relaxed. “I don’t know how she knew I was the artist,” Winn said. “Maybe she smelled the weasel on me.”

If her weasel boxes were born out of childhood fears, Winn’s Human Series had a more Old Testament genesis; like Eve herself, it started with a rib. While in Manhattan, one of Winn’s friends found a bin of human bones for sale and bought her a rib. “It was the best present ever,” she said—high praise from a woman whose husband gave her a mounted mongoose attacking a cobra for her birthday, and fashioned an aluminum, ’50s-style ray gun for their first wedding anniversary. Winn decided then to use human bones in her art. “It was the best thing I ever thought of.” Since then, she has made around twenty painted triptychs containing human bones.

She didn’t want to tell me where she gets her bones. “That’s all anyone asks,” she said. “I want to joke and say I found them in a bag in the park.” She’s not being secretive, but she doesn’t want to break the spell. The human remains she uses in her art are heavy with mystery, and they inspire questions about the living bodies they once supported. Whose flesh hung on these bones? Did they belong to a man or woman? How did these people die? She writes fantastic biographies for the bones in her Human Series. “At the age of 17, Seraphine was struck by lightning while gathering plums in her father’s orchard,” begins one story. Another starts with “Xenocrates was born in Delphi during the exact moment of a solar eclipse.” Winn works the bones into triptychs painted with scenes of these imagined lives. “There is a magic I am trying to create,” she said.

In banal reality, human bones are surprisingly easy to obtain. Winn sources most of her acquisitions from Berkeley, California, where dealers sell off pieces from broken anatomical models. The Bone Room, one Berkeley retailer, takes online orders and ships internationally. Its adult skulls start at around $700. A full rack of human ribs costs $260; kneecaps will set you back $75 a pair. According to Canada’s Criminal Code, it is legal to possess, buy, and sell human bones, as long as they have not been “improperly or indecently” interfered with. Still, boxes of human remains tend to arouse the suspicions of customs officials, and Winn’s shipments take a long time crossing the border.

She seeks out “third-class bones,” specimens that are old, stained, and unloved. “Somebody died, and these are their remains,” she said, “and they’re in a drawer collecting dust. I take them, and I create something new and give that person a new life.” The bones originally came from India or China, but that is all she knows about them. She rarely learns the gender of the owners. The small bones—vertebrae, sacra, and sternums—she uses most often in her work are nearly impossible to sex, although she sees some bones as feminine. The collarbone and the scapula are female, she said, though she is not sure why—something about the smoothness of their surfaces, or their gentle curves. Perhaps these bones suggest femininity because the collarbone and the scapula are considered beautiful parts of a woman’s body.

The artistic display of human remains is an ancient tradition, and was especially prominent in early Christianity. Churches scrambled to obtain sacred relics as a means of attracting congregations to their pews. Body parts of saints and martyrs were especially prized, even if their authenticity seemed dubious. At one point during Christianity’s confused adolescence, at least three churches claimed to possess the preserved head of John the Baptist. Jesus’s and the Virgin Mary’s ascensions into heaven were rather inconvenient for relic dealers as there were no holy corpses to display. Instead, vials containing Christ’s blood and Mary’s breast milk appeared, as did Jesus’s foreskin and baby teeth. The veracity of these remnants was unimportant, as long as devotees believed in them, and believed in their stories; the miraculous lives of Christian saints and holy men from other faiths imparted spiritual powers to their remains.

But Winn’s anonymous bones come with no such narratives, so she creates fictions for those whose true biographies remain unwritten. A discarded clavicle inspired the story of Odette, the Patron Saint of the Damned. A humerus gave rise to the tale of Lalazar, a priest’s apprentice who saw demons lead plague victims from their deathbeds. A scapula told the tragedy of Horishi Kiku, a tattooist whose designs magically came to life. Haunted by her powers, Kiku committed suicide by tattooing a poisonous snake onto her own chest. Winn hopes her triptychs create a “second coming” for her nameless, storyless dead. When they are mounted, she feels an energy emanating from the bones that does not exist beforehand. She is not a terribly spiritual person, but she can sense the life in them.

She composes these biographies and assembles the shrines with great care and respect. She hopes the bones’ unknown “donors” would approve of their reincarnations. This is why she did not, at first, tell me about Bijou the Bear Handler and her sister, Piranha-Hanna. For these pieces, Winn cut a set of little shark teeth and inserted them into the empty tooth sockets of two human jawbones. According to her story, the mandibles belonged to twin sisters born with jagged teeth who ended up as sideshow performers: Bijou in Russia, Piranha-Hanna in America. “I feel a little bit guilty,” Winn said, because these two pieces break her rule about being respectful to the bones’ owners. “They may not like these teeth. I mean, would you? ”

Shark-toothed twins notwithstanding, the aim of Winn’s Human Series is to restore the collective space between the living and the dead. Through most of the past two millennia, Western cultures had an intimate relationship with their dead. Cemeteries moved from outside the city walls and into the churchyards, and the spiritual commingling between the living and the departed formed a single community. Modern secularism severed this closeness, and death became something to fear, to avoid, and to hide away. Winn’s work seeks to change this. Having the dead not just among the living, but hung in the living room, forces us to re-examine our relationship with death and become comfortable in its presence. “Death is part of life,” Winn told me. “It can be sad—I’ve had people I love die—but sometimes it is the perfect ending.”

I gave the skull back to her when I stood to leave her home. I’d been holding it for two hours, and had passed its physical and symbolic weight from hand to hand. Its smell still clung to my fingertips and lingered in the back of my throat. I pointed out that the aroma reminded me of sour milk.

“Interesting,” she said. “I’m going to have to go and sniff my bone cupboard.”

This appeared in the January/February 2011 issue.