Sometime this year, the federal government is expected to introduce legislation that will pave the way for fee-simple (read: private) land ownership on First Nations reserves. According to its champions—former Kamloops chief Manny Jules and on-again, off-again Harper adviser Tom Flanagan—the new law will generate business efficiencies, investment opportunities, and individual prosperity for the 300,000 Native people living on reserves in Canada.

Editorial boards and political affairs observers have commended the First Nations Property Ownership Initiative, a working proposal crafted by Jules and Flanagan, along with Christopher Alcantara and André Le Dressay, in their 2011 book, Beyond the Indian Act: Restoring Aboriginal Property Rights. Proponents, who include a handful of First Nations, dismiss the alarms raised by most of the 600-plus Native communities in Canada, as well as Native studies scholars and the Assembly of First Nations. The Globe and Mail’s John Ibbitson has summarized their objections thusly: “The first is that native land is traditionally communally owned. Private property is yet another assimilationist Western concept being imposed on native culture. The second is that once reserve members own their land, they can sell it to non-natives, eroding the land base.”

Ibbitson rejects these concerns out of hand, arguing that “the legislation will be strictly voluntary. Only those first nations that want to embrace the concept of private property will do so.” This line of reasoning presumes that communities and individuals driven to desperation can freely engage in decision making, when in fact many of them will succumb to a coercive land grab that has been 500 years in the making. He also contrasts the proposed legislation with the US General Allotment Act of 1887, better known as the Dawes Act, pointing out that it was involuntary. He is not alone in dismissing the nineteenth-century law. Backers of the First Nations Property Ownership Initiative regard its dismal legacy as a trivial aside, a laughable historical analogy: different time, different place. But as Cherokee novelist and 2003 Massey Lecturer Thomas King observes in his new book, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, “When we look at Native–non-Native relations, there is no great difference between the past and the present.”

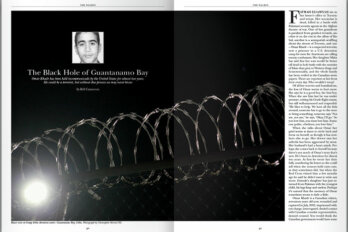

The Price of Freedom

Two billionaires buy up Europe’s last fiefdom

Andrea Wan

Until 2008, the small island of Sark, in the English Channel, was Europe’s last fiefdom. For centuries, a seigneur ruled in place of the British monarch and upheld the feudal constitution. After the billionaire Barclay twins, David and Frederick, bought a private island off Sark’s coast in 1993, they launched a series of lawsuits in the name of human rights and democracy to chip away at the state’s constitution. The Barclays now own almost a quarter of the island, employ over 170 of its 600 inhabitants, and publish its only newsletter. They have met with considerable resistance from residents who question their true motives: in 2010, two years after the island held its first free election, David Barclay tried unsuccessfully to buy the seigneur’s title and residual legislative powers for two million pounds.

—Vanessa Pinto

Sponsored by Massachusetts senator Henry L. Dawes, one of many sincere reformers who sought to fix America’s “Indian problem” after the Civil War, the Dawes Act empowered the president to subdivide reservations into 160-acre parcels that would be “allotted” to tribe members. The idea behind the sweeping legislation was to nullify treaty obligations and de-tribalize Indians through forced acculturation—what Teddy Roosevelt benevolently described as “a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass.” Eliminate reservations, dissolve tribes, and, voila, Indians are transformed into self-supporting citizen farmers and ranchers, integrated into the mainstream economy, and insulated from the forced removals that had previously characterized relations between Indians and the US government.

But what to do with the excess land after the president allotted a reservation? The surplus would be sold on the open market, with the government holding the revenues on behalf of the tribes. And sold it was—to white farmers and ranchers, railroads, timber companies. By the time John Collier, commissioner of Indian Affairs under Franklin Roosevelt, convinced Congress in 1934 that allotment was an unequivocal failure and a national embarrassment, tribal lands in the United States had plummeted from 55.8 million hectares to 19.4 million, half of which was arid or semi-arid desert. However noble the savage, it is no small feat to raise wheat and livestock in the desert while the federal government mismanages your royalties.

The Dawes Act, along with the supplementary Dawes Commission of 1893 and the Curtis Act of 1898, unleashed a bonanza for mining and petroleum interests, including Standard Oil and 3M. (And I would be surprised if resource extraction companies, looking to expand their operations or secure rights-of-way on reserves in Canada, were not quietly studying the unscrupulous tactics of their allotment era predecessors.) For American Indians, the Dawes Act proved to be a disaster that obliterated tribal land bases, imposed the rights and responsibilities of land ownership (taxes, foreclosures, distressed sales, the legal and financial complexities of property) on allottees who did not ask for it, and left those not formally recognized as Indians on the government rolls homeless. While Senator Dawes did not intend it, his legislative hobby horse destroyed communities; uprooted and broke apart families; sent many into abject poverty and others to bankruptcy; disrupted land-based education and traditional knowledge; and destabilized tribal political and legal systems for generations.

But as Native humorist Will Rogers once said, “If there is one thing that America does worse than any other nation, it is to try and manage somebody else’s affairs.” Two decades after Congress scrapped allotment in 1934, it once again attempted to convert tribal lands to fee-simple ownership, with the Indian Termination Act of 1953. This, too, was disastrous.

Is the 3.2 million hectares of reserve land held in trust by the Canadian government as economically productive as it could be? Likely not. But we should be cautious of productive versus non-productive talk, especially when it comes to a Native land base that, in a country of 909 million hectares, is already minuscule. Thomas King calls this dichotomy “the logical fallacy that has haunted Indian history and policy in North America since contact—to wit, that all people yearn for the individual freedom to pursue economic goals.” Simple discussions of dollars and cents, mortgages and investment capital fail to consider the symbolic, religious, and cultural purchase of communal lands for the larger Native community: Status and Treaty Indians, as well as non-Status Indians; those on reserve and those off; those who can vote in band elections and those who cannot. Nor do current conversations entertain the possibility that band membership might someday expand through means other than birth—that Ottawa’s punitive “two-generation cut-off clause” might be replaced with community-specific definitions of citizenship. Indeed, as Metis-Cree journalist Miles Morrisseau has pointed out, the only thing we know with any certainty about the top-down legislation “is that First Nations will have less land than before.”

Yes, the First Nations Property Ownership Initiative is intended to be voluntary. Early drafts of the Dawes Act called for voluntary allotment, too. But it is curious how the fine print can change at the last minute—especially when it concerns Native issues. In the debate over private ownership, smug dismissals of the General Allotment Act should give us pause, not because Canada will inevitably repeat America’s mistakes, but because legislators and policy wonks seem so convinced that it won’t.

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.