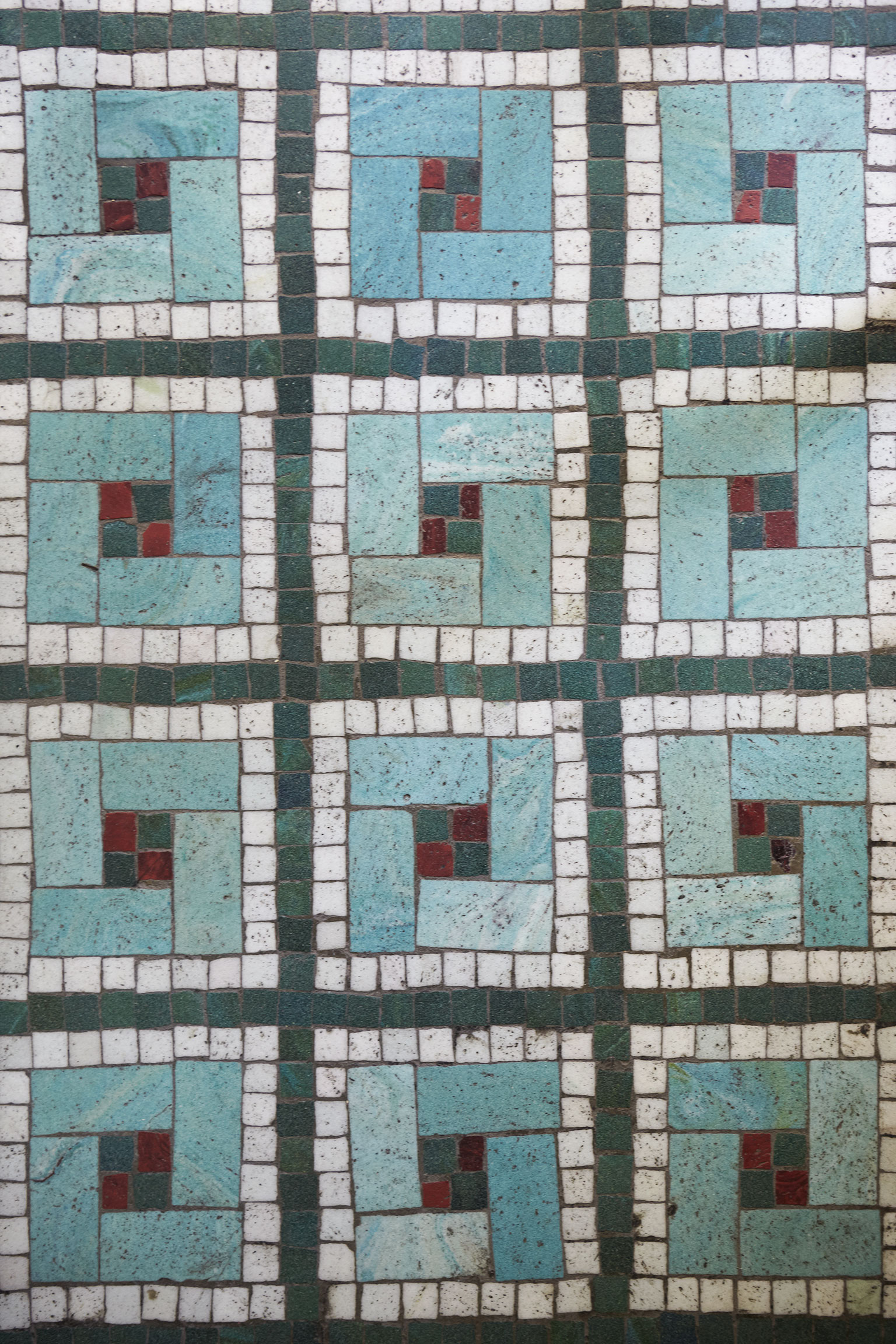

It took ninety-nine days to build the Southam Press Building in 1908. And befitting the crown of a publishing empire, jewels were affixed throughout: Striking tile work in the main stairwell. A stained glass street number above the front doorway. Fireproof reinforced concrete beams. A state-of-the-art sprinkler system, just in case. Red curtain walls by the Port Credit Brick Company. Sills, lintels, and coping—all of it Canadian.

Southam occupied 19 Duncan Street for fifty-nine years. By the early 1960s, the basement was filled with modern offset presses. Colouring books were printed on older Crabtrees on the second floor. There was a bindery on the third, along with storage for the maps and pamphlets Southam produced for Esso (that tiger you put in your tank was likely printed here). There were letterpresses, typesetters, composers, and salesmen scattered throughout the six floors. And when everything was running at full tilt, you could feel the building sway—ever so slightly—east to west.

The shine had long since worn off when, in 2003, Ken Alexander and David Berlin leased 4,351 square feet for a new magazine about Canada and its place in the world. They didn’t know much about magazine publishing at the beginning; they knew even less about decorating. They erected paper-thin walls, with some offices being far too big and others far too small. On the advice of an eccentric designer, they painted everything taupe—which didn’t sit well with the art department. Then The Walrus experienced its first Canadian winter, and along with everyone else the art department realized that wall colour was nothing compared to radiators that never worked.

Anybody who has ever talked to a Walrus editor or fact checker on the phone knows about the fire trucks. For years, Pumper 332 across the street was the busiest fire station in the country. It lost that distinction in 2012—but try telling that to Shelley Ambrose, the Walrus Foundation’s executive director, who famously would yell at the sirens zooming past. (She would also open her sash window and shout “Get a job!” at the Big Bike, which did laps around the building every day in the summer under the power of corporate team builders who clapped along to “YMCA” and “I Gotta Feeling” with far too much enthusiasm.)

Editors can tolerate a lot: cramped working conditions, flickering lights, late copy, mismatched second-hand furniture that would make even a university student blush. But noise is the exception. Sure, there were pleasant sounds at 19 Duncan. Most mornings, police horses clip-clopped their way down Adelaide Street West, just outside my window. I always smiled when I heard their hooves approach, and would stand to watch them pass. (My smiles grew larger when impatient cyclists rushing to Bay Street would ride through the road apples.) But for every horse, there was a cougar bar across the street blaring music at 3:30 p.m. There was the summer the landlord repointed all the brickwork and spent weeks jackhammering a concrete bridge that connected our building to the one immediately south. There was the time the band Hedley filmed their music video for “Kiss You Inside Out” on the corner: “I don’t know if you’re ready to go where I’m willing to take you, girl.” After two dozen takes, none of us cared where they were going, as long as they hurried up and went.

But the loudest, most disruptive sound we heard came, one sweltering afternoon, from within. We were hours away from sending the magazine to press, and I was sitting in the managing editor’s office, staring at proofs. Suddenly, a shuddering ka-thump came from near the black and white photocopier. Shrieks and shouts and holy craps followed. Without warning, our hefty air conditioner compressor had fallen from the drop-tile ceiling and slammed into production director Sharon Coates’s desk before landing on the floor. Sharon—whose name has appeared in every issue of the magazine—wasn’t at her desk at the moment, otherwise she may have died of fright. Shelley promptly told everyone to go home. The sky was falling at The Walrus, and not in the financial sense this time. Predictably (for anyone who knows me), I kept the fact checkers at their desks, issuing them symbolic hard hats and a round of tallboys. We had an issue to get out the door, and these were the conditions we had come to expect at 19 Duncan.

Today, The Walrus moves to the other side of Yonge Street, into a well-preserved bicycle factory that was built in 1895. Our new neighbourhood, Old Town, is quieter and more historic than the Entertainment District, and we will encounter less vomit on the sidewalks as we make our way to work on Monday mornings. Our days will be quieter, too—the better for editing. We won’t have to contend with throngs of moviegoers when the Toronto International Film Festival rolls around in September, and there will surely be fewer fire trucks passing by.

Who knows what will happen to the wonderful mosaics that countless so-called Walrii walked across countless times each day. Who knows if the condo developer putting up a fifty-seven-storey tower will save the faded Southam Press sign painted on 19 Duncan’s southern facade. Who knows if any of us will actually miss what always felt more like a frat house than an office. But there was something right about spending all those years in a building that was as proudly Canadian as we were, even if none of us realized it at the time.