William Krehm once compared the Spanish Civil War, when it still seemed as if the anti-fascists might win, to a sunrise—a brief moment of light that was eventually clouded by defeat, and then swallowed by the Second World War that covered all of Europe in darkness, obscuring the stand made by those who tried to stop fascism’s first rise.

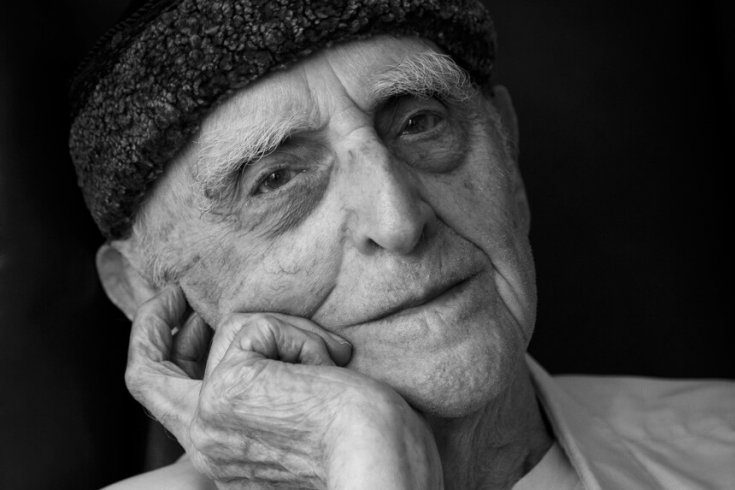

He is now one of the very few who can remember how that light felt and why it was worth fighting for. Krehm was once one among tens of thousands of international volunteers who went to Spain during its civil war of 1936 to 1939 to fight a fascist uprising led by Francisco Franco and backed—with weapons, soldiers, and the terror-bombing of defenceless civilian towns—by the armed forces of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.

More than 1,600 volunteers were from Canada, a legion of lumberjacks, relief camp workers, miners, immigrants, unemployed, and a few intellectuals including Krehm. Their lives had been crushed by the Great Depression and politics inflamed by a rising tide of fascism that the Western democracies preferred to appease or ignore. Some 400 Canadians died in Spain, left where they fell or buried in unmarked graves. Of those who survived, all but Krehm have since died.

The last American volunteer, Delmer Berg, died earlier this year, eliciting an unlikely tribute from US Senator John McCain who saluted Berg, a communist, because he “ransomed his life to a lost cause, for a people who were strangers to him, but to whom he felt an obligation, and he did not quit on them.” Stan Hilton, the last British veteran of the war, died in October. Of the 35,000 internationals who joined Spain’s fight, only a small handful from other countries may still live.

Krehm, who turned 103 on November 23, deflects inquiries about his longevity and unique status. He calls the question ridiculous. But there is no uncertainty about why he went to Spain in the first place. The answer is as clear to him today as when he was a recent graduate of the University of Toronto eighty years ago. “If one did not open one’s mind to what was happening in countries like Spain, one was blind to what is liberty,” he says. “Spain had reached a point that cried for democracy.”

Among foreigners in Spain, Krehm was part of a tiny minority. Most volunteers enlisted in the International Brigades, which were organized by the Soviet Union’s Communist International—even if many of the Canadian foot soldiers in them were not party members, or were indifferent communists. The last Canadian member of the International Brigades, Jules Paivio, passed away in 2013. Krehm’s politics were far more revolutionary. He joined the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, or POUM, the same unit with which George Orwell served when he was shot through the throat on the Aragón front. The two used to chat in Barcelona cafés.

Krehm believed the brand of communism propagated by the Soviet Union and its allies in Spain was little better than Franco’s dictatorship painted red. He dreamed of radical revolution. And in parts of Spain, especially in Catalonia, something like that dream erupted in the early days of the civil war. Workers and farmers took control of their land and ruled themselves. “All the lines of all the labour songs that had been written seemed to have taken on flesh and spirit and to be marching in Spain. It was too good to be true,” Krehm said in an interview in 1965.

For a time, the various elements of Spain’s anti-fascist coalition put their differences aside to focus on defeating Franco. It didn’t last. Abandoned by the Western democracies that should have been its allies, the Spanish government became increasingly dependent on the Soviet Union. It outlawed the POUM in June 1937. Krehm, who was a propagandist for the party rather than a soldier, was among those arrested. He was freed after three months in jail—an experience some of his comrades in the POUM did not survive. Krehm’s memories drift to Spain and then to Latin America, where he spent eight years as a foreign correspondent after the war, and back to Spain. “I think that I learned a great deal about the development of revolutionary thought in Spain, or at least in large portions of Spain, and I thank my stars that I was able to participate in that,” he says.

Krehm says he’s proud of what he tried to accomplish in Spain. He points to a poem written by Charles Donnelly, an Irish writer Krehm knew who died fighting outside Madrid as part of the International Brigades. “And I’m sure that the father of my friend here would be very proud of what his son is up to,” he says.

Besides, revolutions are never really defeated, at least not forever. “I remember this above all in Spain, that starting with the mountains and working towards the sea, there has been a huge process of human revolution,” Krehm says. “It can be buried for a while but it is bound to assert itself.”