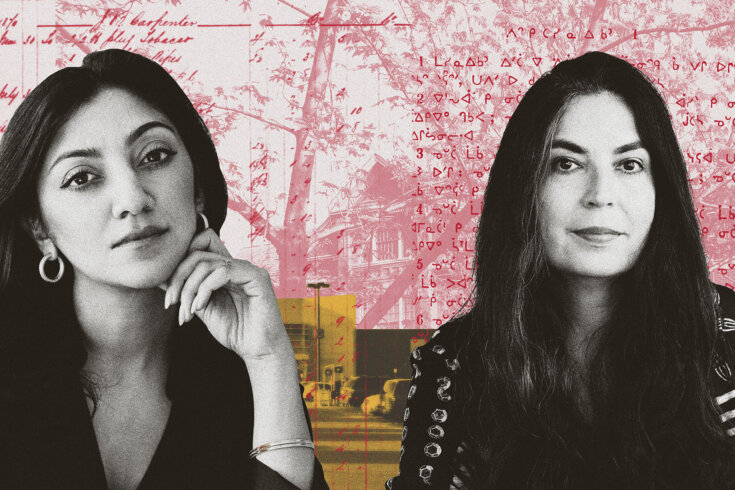

In The Knowing, Tanya Talaga reaches back four generations to piece together her family’s history and the story of how her great-great-grandmother Annie went missing.

The Anishinaabe author, journalist, and documentary filmmaker’s third book is a forensic investigation into the ruinous colonial ideology that caused Annie to be institutionalized for years—the same ideology that propped up residential schools across the country where thousands of Indigenous children ended up missing or dead. The Knowing—released this past August—cements Talaga’s reputation as a force in not only constructing colonial history rarely taught to Canadians in school but also for showing how that history reverberates today.

My own memoir, In Exile: Rupture, Reunion, and My Grandmother’s Secret Life, also digs into a family mystery. It examines the colonial project in the Indian subcontinent and how it impacted ordinary women like my grandmother, who disappeared from the lives of my father and his six siblings. Talaga spoke with me about how she knew she was ready to take on the story, the connection between the colonial extraction project and residential schools, and the internal compass that guides her to the stories she pursues.

SA: When did you feel like you were ready to look into what happened to Annie?

TT: My mom had been asking me for a really long time to find Annie. And I inherited my uncle Hank’s file folder that contains notes and letters that he had written and photocopies of the family trees of all these people—I had no idea who they were. I received it years ago, but I didn’t look at it very often, because it was just so daunting. I had to be ready to do it.

Someone who is an archivist and had read my two other books told me, “You know, if you ever need any help with anything, ask me, and I can help.” Around the same time was the discovery out of Kamloops of the 215 children buried there. It was becoming apparent to me that it was all pieces of the same story. I had this voice in my head for the longest time saying: You have to do this, you have to find Annie. And it just became really loud.

SA: Your book chronicles how the arrival of Christianity provided a religious justification for the stratified societies being created. You drew the line between residential schools run by various denominations of the Christian church and this larger economic project of extraction that began with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Tell me just a little bit about how important it was for you to make the argument that residential schools were an intentional part of this colonial extraction.

TT: The governors of the HBC were concerned with making sure the Crown had money. It was all about lining the pockets of the London businessmen and families who fuelled the project of the fur trade and slavery.

That was combined with the feeling of superiority that the colonizers had, especially when it came to Indigenous people, because we were “savages”—we weren’t Christians; we lived with the land; our languages were completely different.

When I looked at these Indian residential schools and the Indian Act, none of it was set up to further the best interests of First Nations people. In fact, it was the opposite. It was to remove us from our land, to assimilate us. But the Indian Act made it impossible for us to become doctors and lawyers or to go to university. So what was the purpose of these Indian residential schools? Look at the day of a student in every single school—it was the same thing. Half of the day is academic, and the other half is working in the field, being in the laundry, learning how to bake, learning how to be a domestic. Why were we doing that? To serve the dominant class. So that, to me, was a definite show of the caste system that was present.

SA: You’re critical of the Anglican Church and the Catholic Church for their role in the residential school system. Was that a sensitive subject to navigate, since these institutions are still a big part of many people’s lives?

TT: There are Indigenous communities that are still incredibly Anglican or incredibly Catholic. I worried about insulting people and upsetting them. But at the end of the day, I think we have to acknowledge this is the truth. While some denominations may be trying to change now, these are the indisputable facts.

SA: The most common question I’ve been asked since writing In Exile, and mostly by people who aren’t writers, is: How do you start to look into your family history? And you go into such detail when writing about who led you where, how you got a certain record from the government, or how you discovered a branch of your own family tree. It really felt like a guide for other people who want to uncover their own history. What advice do you give to people?

TT: When it comes to First Nations or Indigenous people, it’s a bit different. A lot of our records are held in the Library and Archives of Canada. And I always tell people: if you’re looking for anything on Indian residential schools and members of your family, start with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, out of the University of Manitoba. That’s a good place to start if you’re looking for a particular student or family member. But if it’s broader than that, this is where it gets harder. For my community, it’s also going to Facebook—every community has somebody who’s really on top of the genealogy. Another is the church archives—trying to find where the church that your family members had major life events happen at, then going back to that diocese is helpful.

SA: You describe returning to places that you didn’t realize were so significant to your family but always feeling drawn to them. How did you tune into that? We all have these intuitive pings and these visceral feelings, but sometimes we just aren’t paying attention.

TT: When I started writing Seven Fallen Feathers, and writing newspaper articles about Northern Ontario, about murdered and missing women, about what’s now known as the Ring of Fire, that all felt to me like I needed to be doing this.

I think all of us have that inner compass. Do you listen to it, or do you not? In my experience, if you don’t listen to that inner compass, things get messy. You get off track. You’re not leading the life you were intended to lead. You know when you’re going the right direction, and you know when you’re not. You feel it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.