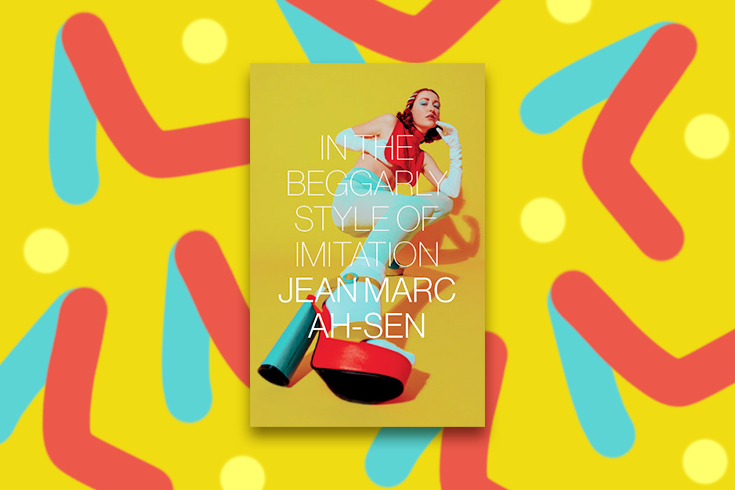

It is hard to know how to classify Toronto author Jean Marc Ah-Sen’s second book, In the Beggarly Style of Imitation (Below the Level of Consciousness). Marketed by the publisher as “a brief survey through the illustrious forms and genres of literary expression,” it is neither a traditional collection of short stories nor a conventional novel. What it does offer is a bewildering, subversive, and at times extremely funny exploration of how style shapes reality.

The book opens with what is probably its most conventional story, “Underside of Love,” in which Cherelle Darwish—the daughter of a character from Ah-Sen’s previous novel, Grand Menteur—witnesses her one-time lover’s tragic transformation into a disease-ravaged tent-dweller. “As to Birdlime” is the story of a roguish migrant who can’t stop mistreating the people around him, while “The Slump” follows a young woman navigating the sexual politics of a university writing workshop. But salted between these longer narratives—five in all—are song lyrics, photographs, a delightful essay on misanthropy, a series of aphorisms titled “Sentiments and Directions from an Unappreciated Contrarian Writer’s Widow,” an interview with a film-studies professor from the University of Toronto, a description of a film called “The Lost Norman,” and a literary cover of Jorge Luis Borges’s famous story “Borges and I.”

According to the introduction, written by someone called “K. Tanner,” the book’s chaotic form is intentional: its contents are a series of experiments composed using the arcane literary techniques of “draffsacking” and “tuyèring” favoured by an obscure literary movement called “Translassitude.” Tanner explains that the stories contained in the book “are ‘exercises of stylistic decadence,’ experiments in bald or disruptive imitation known as the ‘parametrics of purity.’” They also note that Ah-Sen has actually authored ten novels, most of them still unpublished, and that he now considers himself to be retired from writing. Apparently, the drawn-out publication of the remaining titles is merely an “administrative formality.”

The catch is that K. Tanner and Translassitude do not exist. Neither, strictly speaking, does Ah-Sen, though the person who appears in the author photo at the back did write the book and does live in Toronto with his wife and children. “Jean Marc Ah-Sen” is a pseudonym and names a character who is also part of the fiction. The contents of In the Beggarly Style of Imitation and Grand Menteur exist in what we might think of as the extended Ah-Sen universe, a capacious and multilayered world of Mauritian street gangs, sophisticated cinephiles, defiant refugees, and libertine art collectors that occasionally overlaps with our own reality.

Readers who go in for this kind of thing will probably find this reason enough to buy the book. Those who just want a believable story with fully realized characters may conclude that In the Beggarly Style of Imitation isn’t for them. But both groups might find themselves wondering whether there is really anything new about this kind of approach more than fifty years on from the famous metafictional experiments of Vladimir Nabokov and Flann O’Brien. Is Ah-Sen cracking open the tired tradition of the postmodern novel? Does he offer bold new answers to old questions?

Read enough criticism of contemporary commercial fiction and you’ll get the sense that most writers and critics these days accept that literature exists to comment on the world in a relatively straightforward way. Fiction’s job—like Stendhal’s image of a mirror carried along a high road—is to reproduce the reality we encounter in a controlled fashion and provide an emotional frame to help us make sense of it. Evaluating books means judging both the writer’s skill at reflecting reality (facility with language, characterization, plotting, etc.) and the degree to which their frame is credible.

This approach can yield insightful criticism so long as it’s used on authors who tackle their writing with the same assumptions. But it also encourages us to imagine a “real” world, one where someone can fall in love or lose their parents or join a cult, and to think of style and tone and diction as merely being tools that help us reproduce a reality that exists independently of them. When a writer pulls it off, realism is a trick with astonishing power. When they fail, they are usually faulted for being insufficiently attentive to what the world is actually like or for lacking the talent to portray it.

Experimental books like In the Beggarly Style of Imitation have no truck with this approach for the simple reason that they don’t (or don’t just) reproduce an experience of the real but are engaged in sophisticated forms of play. Effective realist prose is often invisible: we don’t think about the sentences we’re reading because we’re lost in the story and the experiences of characters who, on some level, have come to exist for us. Experimental writers, on the other hand, often see drawing attention to the artifices and conventions that undergird our encounters with literature as part of the point. In novels like Eimear McBride’s A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, needlessly complex, pretentious, or contrived prose doesn’t miss the mark; it’s just another part of the game. The pleasures of this kind of fiction are intellectual, like the puzzle-solving satisfaction of translating a language you only partially understand. Reviewers who expect the prose to serve the story and the characters dismiss such books for being insufficiently readable and treat their virtues as vices.

In the case of Ah-Sen’s work, this desire to draw attention to the artificial nature of the story can be seen not only in his metafictional approach but in his intentionally archaic style. Ah-Sen’s sentences carry the reek of the eighteenth century: its long Augustan cadences, its elevated diction, its leisurely clauses, and its pungent use of words like handsel, rakehell, and pulchritude. The book’s fiction centrepieces, “Underside of Love,” “The Slump,” “Swiddenworld,” and “As to Birdlime,” might be largely set in modern-day Toronto, but they are mostly narrated in mannered, circuitous prose that keeps the reader at a distance from the action of the story.

Take the following paragraph from the opening section of “As to Birdlime”:

Leaving behind a young mother with child, Ste. Croix travelled to the Home District to seek his fortune; to ply his abilities in a situation where his standing might not fail him gainful opportunities. He felt wondrously justified in his action, for that he reasoned he would be better suited in a pecuniary sense to support his stripling; even if such support came at the cost of being unable to witness the progress of his little Aldegonde by his own account, at the very least—he would console himself when thoughts occasioned on the subject of his conscience—his child would not grow hungry or unhoused; draped in rags to be sure, but woe betide he who had neither the fortune nor the good sense to view it as a blessing, draped in something nevertheless.

In three sentences, this paragraph breaks just about every rule of contemporary prose writing. Over the past 100 years, we have become accustomed to an Americanized English that privileges short sentences, simple language, the active voice, and efficient clauses joined by basic conjunctions like “and” or “because.” Writing like Ah-Sen’s, which layers prepositional phrases and nestles clauses within clauses, reads as old-fashioned, harkening back to the prose of Swift and Fielding and Johnson. This is compounded by the use of archaisms like “wondrously justified” and “woe betide,” which put us at a decided remove from the narrative action.

This creates two main effects: a sense of farce and a feeling of psychological distance. The discord between Ste. Croix’s coarse antics and the elevated tone in which they are described is comic, but it also mirrors Ste. Croix’s own inflated sense of dignity. The clause offset by em dashes functions as a narrative turn in which we see that the sophisticated diction mirrors and betrays Ste. Croix’s hypocritical self-image. The style becomes a dimension of Ste. Croix’s characterization and, in a metafictional sense, a commentary on the literary trope of the “rake,” the amoral young man whose single-minded pursuit of pleasure leads to his own destruction. After all, the difference between a rake and a sociopath usually comes down to a question of narrativization.

But, aside from its metafictional qualities, In the Beggarly Style of Imitation can be enjoyed purely as a romp through different styles and literary forms. At less than 200 pages in length, the result is a masterpiece of economy. The book doesn’t have time to drag: each story offers its unique flavour and sticks around just long enough to excite the palate before being replaced by something completely different. Style, for Ah-Sen, is always on the move. It’s where the sheer pleasure he takes in language is met by a formal structure that can contain its excesses. But is that enough?

Encountered on its own, Ah-Sen’s eclecticism might seem merely idiosyncratic, even cack-handed. But, in the context of a project apparently intended to explicitly “reflect the storied genesis and formalization of elements that would become recognized as the modern novel,” it becomes brilliantly subversive. By blending contemporary forms of meta- and autofiction with the language and idiom of literary classicism, Ah-Sen encourages us to imagine ourselves as mimetic creatures.

These themes emerge most clearly in pieces like “Ah-Sen and I” and “Swiddenworld: Selected Correspondence with Tabitha Gotlieb-Ryder.” In the former piece, Ah-Sen sets himself the challenge of writing his own version, down to the word count, of Borges’s page-long meditation on the relationship between Borges-the-man and Borges-the-literary-edifice. What he offers is a true literary answer: where Borges described his public self devouring everything his private self produced, Ah-Sen describes the feelings of resentment and devotion his writer self—at once a burden and a conduit for libidinal release—inspires in him. To Borges’s famous last line (“I do not know which of us has written this page”), Ah-Sen offers a distinctly twenty-first century rejoinder: “I do not care which of us has written this page.”

In “Swiddenworld,” the drama of art, authenticity, and power is staged in a series of letters between an art collector and an agent whose avarice for modern art (and decidedly kinky forms of sex) leads to a series of comic betrayals. As a piece of writing, it’s pitch perfect, swinging between the banalities of formal correspondence and a kind of ludicrous erotic badinage reminiscent of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill, the Marquis de Sade’s Justine, and the poetry of John Wilmot. It’s also the story that most explicitly addresses the problems of art, style, and imitation suggested by the book’s title. The relationship between the collector, Serge Mayacou, and the agent, Tabitha Gotlieb-Ryder, revolves around the tension between Mayacou’s sexual apprenticeship under Gotlieb-Ryder and his attempt to replace her as a professional acquirer of art objects. In both cases, Mayacou is learning from Gotlieb-Ryder and, in a sense, becoming her. Mayacou ends the story by debasing himself entirely to Gotlieb-Ryder, but this debasement is also a kind of mutual fulfillment. The relationship between sub and dom is a symbiotic one, after all, and Gotlieb-Ryder needs Mayacou as much as he needs her.

The fact that Ah-Sen chooses to handle this exploration of imitation and power by imitating a long-established but rather tired literary form, the epistolary novel, only serves to heighten the irony he raises: forms and styles remain vital only so long as they are imitated, and by choosing who and what to imitate, Ah-Sen is placing himself in no less a position than that of arbiter of the life and death of literary styles. The imitation of style may be beggarly, but it is through the imitating supplicant that a style’s value is established and maintained. Where the Romantic tradition sees art as the expression of some kind of preexisting individual, the classical self is created by the forms of expression available to it. Novels, plays, operas, Twitter accounts—all offer avenues for creating identities of our own by refining and adapting the kinds of things we see other people doing. And, in the endlessly generative process of artistic production, what we produce becomes, in turn, a mimetic model for others.

Ultimately, “Jean Marc Ah-Sen” is the fiction that makes all of these other fictions possible, that knits together the letters of Serge Mayacou and the interview with Bart Testa. For this very reason, trying to intuit where Ah-Sen the writer ends and the Ah-Sen you might find walking down Dufferin Street begins is a fool’s errand. They are products of each other, just as they are products of Fielding and Borges and Mauritius and Toronto.

At a time when writers—and writers of colour in particular—are described as being voices rather than having them, Ah-Sen offers a vision of the self that is compulsively creative and ecstatically pervious to the world. Ah-Sen contains multitudes, and in this marvelous book, he reflects the multitudes that have created him back to us, a hall of infinitely distorting mirrors as old as art that will carry on for as long as his style inspires imitators.