A s Canada faces the threat of US president Donald Trump’s 25 percent tariffs and the painful process of industrial closures and restructuring that will result, the fight to save Algoma Steel in the early 1990s is an inspiring story about reclaiming our economic future. It is also a story of how labour unions have responded in such moments.

In January 1991, Dofasco, the steel-making giant based in Hamilton, Ontario, made an announcement that shook the Northern Ontario community of Sault Ste. Marie to its core. Dofasco was going to write off its $740 million investment in Algoma Steel, Canada’s third largest steelmaker, leaving 6,000 workers at the mercy of its creditors. In other words, the steel mill and all those jobs seemed to be over.

A senior civil servant in the Ministry of Northern Development estimated that Algoma needed $200 million to pull through. “All they need is an optimist with $200 million in the bank.” The joke prompted a senior adviser to Premier Bob Rae’s Ontario New Democratic Party to say that “one way or another, we were about to acquire an industrial strategy.” Despite the uncertainty, the premier’s office remained optimistic. “For all the gloom, there was a strangely positive tone to the meeting, produced . . . by the sense that this group and this government have what it takes to deal with the crisis.”

One of the reasons for optimism in winter 1991 was the fact that the United Steelworkers of America, the union at Algoma, had far more experience with worker buyouts than any other union in North America. Faced with a crisis in the US steel industry in the early 1980s, the United Steelworkers had brought on Ron Bloom, a Wall Street investment banker, as an adviser for industrial restructuring and worker ownership.

“There was a period of time when Bloom’s firm was working almost exclusively for the Steelworkers in the States on various industrial restructuring projects,” Hugh Mackenzie, former research director for the union, told me.

The Ontario NDP brought the parties together and worked out a deal. Its insistence that any solution had to include the union was pivotal, as was its commitment to guaranteeing bridge loans to keep the steelmaker in operation while negotiations dragged on. The rescue of Algoma required extraordinary political will. Looking back, there is every reason to believe that Algoma Steel would not have survived had any other political party been in power at that moment in history.

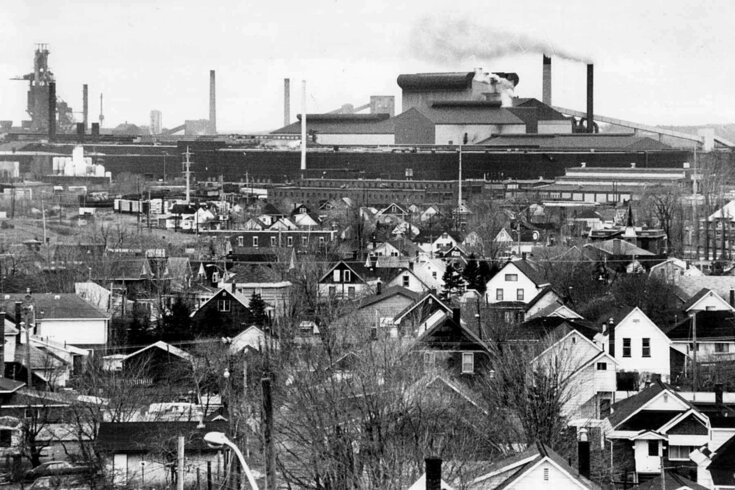

S ault Ste. Marie is located on St. Mary’s River where the waters of Lake Superior descend into Lake Huron on the long journey to the Atlantic. The river’s enormous water power drew American businessman Francis Hector Clergue to the Sault with the dream of developing a massive industrial complex on the northern frontier. Before his corporation collapsed in 1903, he had built a paper mill, a steel mill, and a railway to bring in iron ore from a mine near Wawa in Algoma district, about 200 kilometres north. But his industries lived on—among them, Algoma Steel.

Dofasco, Canada’s second largest steelmaker, but non-unionized, purchased Algoma Steel in 1989, promising to modernize the Sault Ste. Marie operation. Dofasco immediately collided with the United Steelworkers, resulting in a 112-day work stoppage in retaliation for downsizing, contracting out, and other issues. When Dofasco suddenly announced that it would walk away from its investment on January 23, 1991, the future of Algoma was put into doubt.

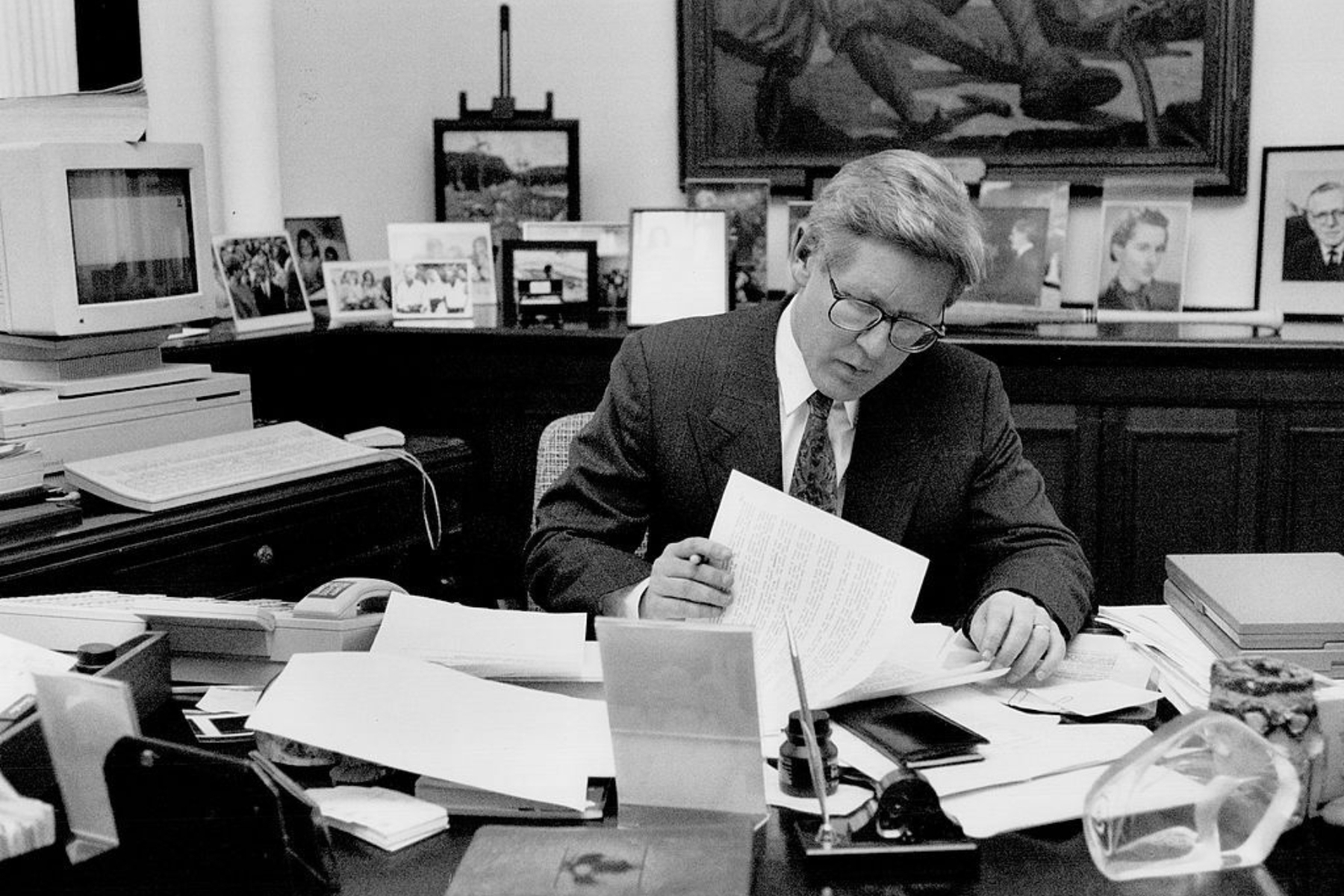

When I interviewed Rae recently, he recalled, “I got the call from the president of the company, from Dofasco, saying we’re going to do this, and I said, ‘You’re not doing anything without talking to us, and you’re not doing anything without talking to the union.’ I said, ‘My door’s open to talk to you, but if you think you’re going to be able to close this place and walk away, you’re wrong.’”

Rae then met with local union officials on January 29, to discuss how best to save the mill, and then with company officials the next day. The sequence of meetings is important here.

After Algoma was put under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangements Act, the United Steelworkers insisted on a long-term fix: if Dofasco “succeeds in getting short term relief, the problems won’t go away. The next time there is a crisis, Dofasco’s responsibility will be diluted even from what it is now. Responsibility will be shared by all those who help short term.” The union called it a trap, adding that it was “interested only in changes that address the problems of long-term viability.”

From the outset of the crisis, the Steelworkers saw a worker buyout as being their preferred option. In a January 30 letter to the premier’s office, the union noted that it had developed “significant expertise both internally and in the consultant community in the U.S. on these matters. Our union is uniquely placed to place the worker ownership option on the table in the case of Algoma and is in a position to offer valuable assistance based on our extensive experience.”

Not surprisingly, the union’s primary objective was “to maintain as much of the operation and as many of the jobs as possible consistent with maximizing long term competitive viability.” On this basis, they were willing to consider “any kind of configuration,” including major restructuring.

Rae brought all the parties to Queen’s Park in March 1991. He “told them that the Ontario government was not going to bail them all out, that they had to find a co-operative and market-based solution, and that we would do everything we could to broker a solution.” Dofasco was convinced to remain involved in the process, and even to develop a new restructuring proposal, given its sizable environmental and pension liabilities.

Dofasco’s May 1991 restructuring proposal would have seen a radical downsizing of the plant, with the termination of three of the mill’s four product lines as well as the closure of the iron ore mine in Wawa. Three thousand jobs would have been lost, and the wages of those remaining would have been rolled back by 14 percent. In this scenario, mill workers would have received minority share holdings in exchange for their wage concessions but no control over their investment. Dofasco also wanted to shift some of the company’s pension liability onto workers by converting the liability into Algoma shares, thereby exposing workers to enormous risk.

There was a dramatic showdown between the union and the company in Toronto. The union brought Bloom, who later recalled that Dofasco’s proposal was “a pretty draconian thing” as it “imposed all the pain on the workers.” The New Republic provided an account of what happened next:

With Dofasco’s restructuring proposal dead on arrival, worker ownership emerged as the last best hope for the mill’s survival.

T he union’s willingness to experiment and take risks led it, with the help of Bloom, to develop the voting trusts strategy, first developed after the West Virginia–based Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel faced bankruptcy in 1982. Concessions were negotiated in exchange for preferred shares that carried full voting rights. By 1990, roughly one quarter of the US steel industry was under some measure of employee ownership, and it had become the central job-saving strategy of the union, at least in the US.

To be sure, Bloom was uniquely positioned to lend organized labour a helping hand. He was what they call a “red diaper baby,” as his parents had met in Habonim, the socialist Labour Zionist youth movement in the 1940s. As a boy, Bloom was sent to the movement’s summer camp each year before he graduated to camp counsellor. “We sang the songs,” he recalled, “but it wasn’t about that. It was a broader sense of identifying with the underdog, and of observing the world through a lens, through people who don’t have as much and aren’t as lucky.”

After graduating from university in 1977, Bloom worked for the Jewish Labor Committee, an American secular Jewish labour organization, and then joined the Washington-based Service Employees International Union, where he soon concluded that the trade union movement needed to better understand the workings of business if it was to survive. To acquire these skills, he went to the Harvard Business School, graduating in 1985, and then made a name for himself at Lazard Frères, a Wall Street investment bank. Soon thereafter, he engineered a hostile takeover of Wheeling-Pittsburgh in order to achieve the desired result.

Bloom described his approach as “dentist-chair bargaining,” in which he “grabs the dentist by the balls and says, ‘Now let’s not hurt each other.’”

By all accounts, he was a brilliant negotiator. “Ron has what I refer to as ass power,” suggested one observer. “He’ll continue to talk about things, explore them, work on them, not letting the other side see what’s really important to him. Even if it’s important, he’ll bargain it away early and work on getting it back.” He later told one interviewer that in 99 percent of bankruptcies, new ownership results, and the existing shareholders are “wiped out, and the people who are the owners are typically the predators. They’re the guys whom the company owed money to.” The United Steelworkers, out of necessity, became one of those predators, using its leverage to win control of failing steel mills.

Bankruptcy was “a combination of law and politics,” Bloom explained. “By politics, I mean power. Creditors get their way because they have the leverage to get their way. It’s, as they say it, ‘an adults only game.’ Everyone is out for themselves, which is fine, but if you have leverage, you use it.”

After considerable preparation, the union’s restructuring plan for Algoma was ready by August 1991. Leo Gerard, a former hard-rock miner from Sudbury, made the public announcement. It included long-term wage concessions, the elimination of 1,600 jobs, mainly through early retirement and natural attrition, and capital investments of $500 million over the first five years. In return, the new Algoma would be employee owned and controlled.

As Ken Delaney from the United Steelworkers explained to me, a “particular set of circumstances” made Algoma Steel “the right candidate for an employee buyout.” There was no corporate white knight waiting in the wings prepared to invest real capital. Dofasco wanted everyone else to “take a haircut,” except itself. “If Dofasco had been prepared to invest money, this might have gone completely different. But nobody was prepared to step up,” Delaney says. Creditors were therefore convinced to go along with the worker buyout. “We were the only dance partner available, to be blunt,” Delaney told me. “It doesn’t matter how ugly you are—if you’re the only dance partner available, you get the dance.”

Pushed into a corner, Algoma’s management eventually agreed in principle with the worker ownership model, but the details needed to be ironed out. Multipartite negotiations dragged on into 1992, and there were moments when these talks threatened to break down. The breakthrough came at the end of nine days of around-the-clock negotiations at Toronto’s Park Plaza Hotel, led by George Adams, a judge of the Ontario Superior Court, who had been brought in as arbitrator.

T he deal was announced by Rae at Queen’s Park on February 28, 1992, ending more than a year of uncertainty. Algoma’s new board of directors now comprised the CEO, five employee nominees, along with seven independent directors, including former premiers of Ontario (Bill Davis) and Saskatchewan (Allan Blakeney). In exchange, unionized workers gave up $2.89 per hour in wages and salaried staff lost 14.5 percent.

Algoma’s new mission statement read: “As equal partners, Algoma and the United Steelworkers of America make as top priority, the creation of an organization that is dedicated to economic security and empowerment of employees and to continuing improvements in productivity and quality.” The new era at Algoma Steel was symbolically marked by the elimination of punch clocks for employees and the suspension of its membership in the local chamber of commerce. On the shop floor, the worker buyout ushered in a period of experimentation.

There were also wider lessons. The Algoma Steel buyout helped Bloom to appreciate just how much leverage trade unions can have during bankruptcy proceedings. For him, the buyout yielded two key insights: “First, you can typically show that liquidating a company is a lousy deal for everyone involved. Second, once you’ve convinced stakeholders that they’re better off with a living company, labor has enormous leverage. The law technically gives lenders and suppliers priority over workers, but you can usually find new lenders and suppliers. The workers, on the other hand, are virtually irreplaceable.”

If Bloom’s role was crucial, so, too, were those of Gerard and Delaney as the three men worked out the union’s successful strategy. The support of the NDP government was crucial at every step. Without question, the Rae government invested considerable time and energy into the buyout of Algoma.

The mill continues to operate today, albeit under private ownership, but the worker buyout has been all but erased from political history. For some of Rae’s senior advisers, Algoma Steel represented “the high-water mark achievement of the industrial policy that we [the NDP government] had in mind.” It was soon eclipsed by the fight against the mounting deficit and the government’s embrace of the politics of austerity under the “social contract.”

Gerard went on to become international president of the United Steelworkers, only the second Canadian to do so. A few weeks after Barack Obama’s victory in the 2008 US presidential election, Gerard received a call from Obama’s transition team, asking for advice on the automotive crisis. He put Bloom on the call, who impressed the presidential aid with his blunt assessment. Bloom ended up managing the restructuring of General Motors and Chrysler for the US government, after which Obama named him his “manufacturing czar.”

“He may only manufacture deals, but that’s been more than enough to retool the Rust Belt,” declared Time magazine in 2010, naming Bloom one of its 100 world changers. But as Ross McClellan, who worked in Rae’s office, quips: “He was our czar first, we beat Obama.”

As Canadians are once again faced with a period of radical restructuring thanks to Trump’s threatened 25 percent tariffs on all Canadian exports to the US—the steel industry likely to be hit particularly hard—there is much to learn from this episode in history.

Adapted and excerpted from The Left in Power: Bob Rae’s NDP and the Working Class by Steven High, copyright 2025. Reproduced with permission from Between the Lines.

On Friday, April 25, join us for The Walrus Talks at Home: Tariffs. Four expert speakers will discuss what the U.S. tariffs on Canada mean, both now and in the future. Join us online. Register here.