The voice on the other end of the line was familiar enough. It was the message I was having trouble getting a grip on.

Suzy, one of my closest and oldest friends, was phoning from her Toronto home. “Matt, I don’t really know how to say this to you. But we’ve decided to go in another direction. I don’t feel like this is working out.”

It was a few sentences that were both simple and entirely complex. But the essence of it was easy enough to summarize: I was being dumped as a sperm donor.

Thus ended a nearly two-year effort on the part of Suzy, her wife, and me to get pregnant. It had never been my idea; Suzy and Jane, then just past their mid-thirties, had sat me down about two and a half years earlier for a talk. They proposed that since Suzy and I went so far back, and with a friendship that ran so deep, I would be the logical person to contribute my dna to their attempt to build a family. I was both honoured and thrilled; I’d never thought of myself as parent material per se, but the idea of helping Suzy and Jane have a baby—they were clearly going to be conscientious parents—while being on board as a godparent seemed appealing, to say the least.

At that moment, the break was extremely distressing. First, I had never really been heartbroken about not having offspring, but for more than two years I’d had plenty of time to daydream about just what sheer joy that might present. Second, the person who was saying it was one of my dearest friends. Suzy and I had met in high school. We were inseparable and told each other everything. She was the first person I ever told that I was gay. I gave a speech at her and Jane’s wedding. I was a pallbearer at her mother’s funeral.

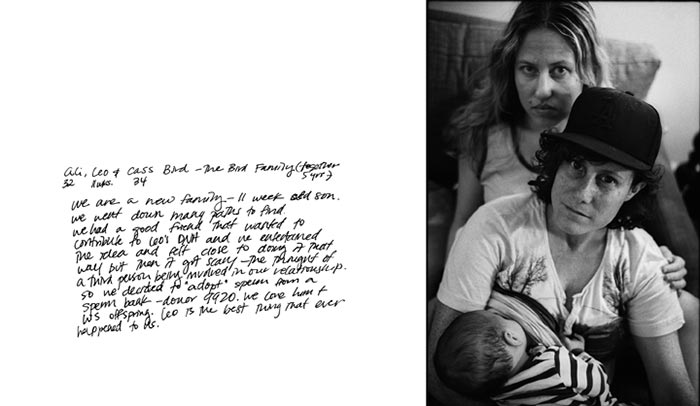

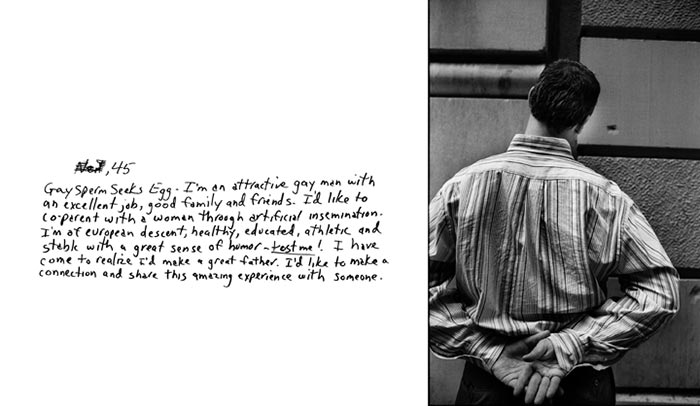

I know that Martin Amis has scolded us about avoiding clichés, but there they were, storming my brain: knife through the heart, kicked in the head, crushed, dumbfounded, thunderstruck. But what I would learn in the ensuing weeks is that I was hardly alone. In fact, I was caught in the gears of the various new machinations emerging from the burgeoning number of queer families, and one particular decision faced by many lesbians aspiring to parenthood. They have the means, but they still need sperm to get the job done. There are two options at this fork in the road: do they go the anonymous sperm donor route, or do they harvest the sperm of a close friend (usually gay)? We might call it the plan A (anonymous donor) or plan B (close gay friend) conundrum.

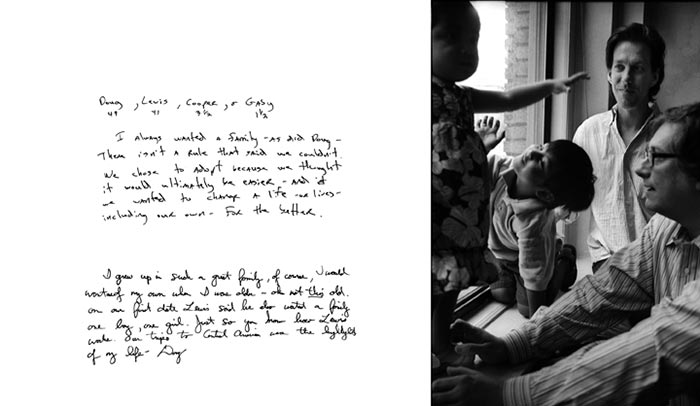

This is but one piece of a gigantic, multi-dimensional puzzle that is the burgeoning universe of queer parenthood. Though there aren’t any statistics on the so-called “gayby boom,” the North American gay and alternative media have been following it for over a decade. A gaggle of articles has appeared about the growing rate of parenthood among same-sex couples. Statistics Canada, despite being one of the very best data-compiling bodies in the world, doesn’t keep such details, and some of the lesbian and gay parents I talked to for this article said that even if the government asked, they’re not sure they’d answer forthrightly, given the community’s long-standing mistrust of such authorities.

Still, according to the legal, medical, and activist experts, same-sex parenting is indeed a growth industry. While gay men, being wombless, are at an obvious disadvantage, lesbians are forging ahead into parental territory at a rapid rate. Mona Greenbaum, a Montreal-based lesbian and the founder of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Family Coalition, says she started the organization a decade ago when she decided to join the maternal sisterhood, precisely because at the time there were no resources, no role models, no one to offer any advice. “We really were isolated back then,” she says. “That was ten years ago. We were essentially alone, or it felt that way.” Not anymore: “Now we have over 900 families in our membership. We conduct workshops where people discuss the issues surrounding parenthood and what the legal boundaries are, and offer meetings where people can exchange notes. When I started, this was a side gig. Now being coordinator has become a full-time job.”

Beyond Greenbaum’s shift into full-time employment, the new emphasis on parenthood—which has moved forward in lockstep with the push for legal recognition of same-sex marriage—represents an epic and controversial change in the gay liberation movement. That term alone now sounds decidedly quaint, but old-time queer activists have expressed dismay at the new directions of emphasis and focus in the gay and lesbian struggle. In particular, consider the words of Jane Rule, the iconic lesbian author and activist, who died last year. She argued vehemently against the fight for same-sex marriage, stating that “what we are pleading for is the state to take greater control over our relationships. I am violently opposed to the common-law provisions.” She also remarked that “policing ourselves to be less offensive to the majority is to be part of our own oppression.” These sentiments now seem to come from an eternity ago. The new attitudes toward same-sex marriage and parenting in the gay and lesbian community are matched by changes in perspectives toward such issues among the larger heterosexual population. At its core, the gay liberation movement made the argument for full equality for all. Its most radical activists have now had their worst fears realized: in many respects, homosexuality has been normalized. Fights over public sex and aids funding have been supplanted by discussions of parental rights and daycare provisions.

Those fighting the hardest for same-sex marriage rights were in agreement on two issues their opponents were also adamant about: same-sex marriage represents a fundamental change to the institution, and it is about the children. The people who were wrong were the ones who thought that once same-sex marriage got through Parliament, the struggle would be over; gays and lesbians who wish to parent are now facing a broad range of legal and institutional challenges, and overcoming these obstacles represents the next battle for the movement.

The ways to parenthood are varied; some adopt, though adopting foreign children is often out of the question (for a time, China provided a great deal of product in the international baby trade—but the country banned gays and lesbians from participating). One prominent Toronto-based lesbian author reportedly dropped $50,000 for a baby from California, a price tag that puts this process out of reach for most. The most practical, common, and growing form of queer parenthood comes in the form of lesbian motherhood—a two-parent household led by two women.

Greenbaum has witnessed and been a part of this change in queer culture. She sighs in recognition when I tell her my own story and explain my status as an ex–sperm donor. As she points out, this has become a pivotal question for aspiring lesbian moms. She has held workshops and discussions on this very choice for lesbian couples, to help them make informed decisions on which path to take.

The pros and cons of plan A were clarified when I visited a Montreal lesbian couple earlier this year. Liliane, a forty-one-year-old stay-at-home mom, and her partner, Joyce, chose to go with an anonymous donor via a sperm bank. The result is their three-year-old son and a newborn. “We did consider the other option. We thought about getting a close friend to do this, but that didn’t last for long,” Liliane says. “We actually didn’t have a close friend we thought would be appropriate. It seemed like we’d really be forcing it if we tried to make a relationship fit the circumstance.” She and Joyce decided to go the anonymous sperm donor route, in particular because they felt having a known donor in the picture might make things too complicated: “We knew that in many regards this means you have a pseudo-parent around, beyond the two lesbian moms. How would that work out? ”

But the sperm donor option has its own set of complications, as Liliane would soon find out. She liked the idea that when and if her offspring wanted to, they could make contact with their biological father or fathers. She and Joyce chose to buy sperm at a clinic where the donor had said he would be open to being contacted by the child once he or she turned eighteen.

Ironically enough, when considering plan A, many lesbians are forced to look south of the border for assistance—this despite the fact that Canada’s civil rights laws for gays and lesbians are considered light years ahead of their American counterparts: same-sex marriage, no ban on gays in the military, and immigration and refugee regulations that recognize oppression of gays abroad. But even so, most lesbian sperm seekers these days must go cross-border shopping. Canada’s laws surrounding assisted procreation have become far more restrictive than in America, where ideas of private enterprise and individual choices in the marketplace tend to eclipse government oversight.

Greenbaum says the legal landscape for sperm banks and fertility clinics operating in Canada shifted in 2004. In March of that year, the federal government passed Bill C-13, the far-reaching Assisted Human Reproduction Act, into law. The government had been trying for some time to come up with legal guidelines around the growing prospect of people conceiving families in new and different ways, with efforts dating back to 1993. But in the public consciousness, the science was moving at an incredibly rapid rate, meaning anxieties were running higher than usual—in particular when the first mammal, Dolly the sheep, was cloned. Suddenly, science fiction was merging with reality, and future shock set in. The result, argue many lesbian moms and their advocates, was that a number of legal provisions concerning surrogate mothers and sperm and egg donation got mixed up with fears about cloning and species crossbreeding. C-13 strictly forbids mixing animal dna with human embryos, for example, while also making paid surrogacy illegal and prohibiting the sale and purchase of sperm.

Gays and lesbians could be forgiven for feeling a bit insulted. The huge chunk of legislation appeared to link procreative techniques that would help them form families with potentially horrific scientific experiments. “I understand, to an extent, where they were coming from and what they were attempting to do,” says Kelly Jordan, a Toronto-based lawyer who specializes in law related to assisted human reproduction, and is herself a lesbian mom. She says she feels the authors of C-13 were probably well intentioned, “but they were short sighted. I see no evidence that surrogates or donors have been exploited for their genetic material. The surrogates can’t be paid beyond their basic expenses—which just means women’s work is getting unpaid or underpaid again. And the banning of paid sperm donation in Canada has simply led to a shortage, which has meant women are forced to go to the US for sperm.”

That is precisely where Liliane turned to be impregnated. She and Joyce visited a US sperm bank’s website, where pleasing slogans welcomed them to the prospect of pregnancy. They looked at photos of potential donors, reading brief statements from each about why they’d chosen to donate sperm. Something in a note by one man touched Liliane. “He seemed sweet to me,” she recalls. “We just felt that this would be the right one. We bought four doses of his sperm for $1,200.”

But she and Joyce would find that plan A came with its own set of surprises, some unwelcome. Their sperm bank claimed donors would be retired after a reasonable and limited number of donations, to keep half-siblings to a minimum. The couple also learned of an online registry where recipients could check out their donors using identification numbers. They signed up, and to their surprise found that their donor was a popular choice among wannabe moms. They also discovered that a lesbian couple they knew in Victoria had used the same donor, and were thus connected to them by dna whether they liked it or not.

“At this point, Joyce called the clinic,” Liliane recalls, “and asked what the protocol was. They discussed things and agreed that this particular donor should be retired. We were quite taken aback that there would be so many people using our donor’s sperm.” The clinic’s website implied that it was notified by its clients when someone had a child through their services. But that assurance left nagging questions, too. “Notification to the clinic of a pregnancy or birth is entirely voluntary, so there may be many they are not hearing of,” Liliane points out. “As well, how do they know this donor isn’t going to ten other sperm banks and donating at the same time? Our child could have quite a number of half-siblings.”

Furthermore, while the sperm bank they went to insisted it had a screening process in place, Liliane has no idea if they asked any questions about donors’ comfort level with lesbian parents. What if their child, at eighteen, ventured to make contact with the donor, only to learn that he was entirely uncomfortable with the child’s family? “I really hadn’t thought of that. It never crossed our minds.”

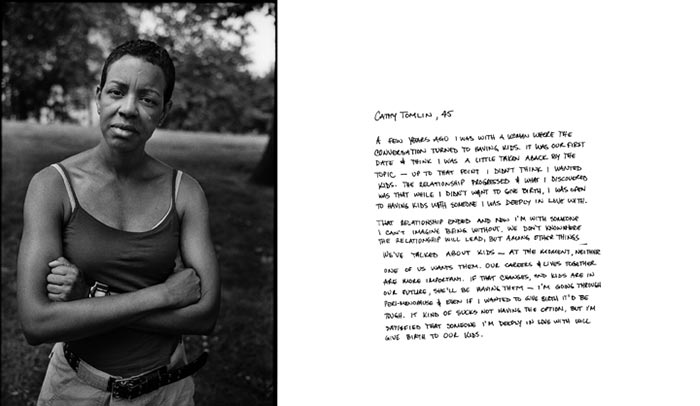

Meanwhile, other lesbian moms feel strongly about having a donor around, acting in a quasi-godparent capacity, so the child can know its biological father as he or she grows into adulthood. Many of those I interviewed say this choice often boils down to a cultural difference. A lesbian couple from France, for example, may have a heightened consciousness of lineage and pedigree. For them, the best choice would probably be to go with a known donor.

Still, plan B has its own set of sub-choices. If lesbians opt for the do-it-yourself, or “turkey baster,” method, things can move along with no state interference. If they have problems getting pregnant, however, and a fertility clinic is needed, then the lesbian moms and their chosen donor can hit another barrier. As the law stands, sperm banks in Canada often reject sperm from gay men, citing the same line of reasoning for refusing them as blood donors: risk of hiv transmission, even with gay sperm donors being tested for hiv, and even with sperm being frozen and held for six months and tested for the virus. In January 2007, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld this ruling, after a lesbian argued that excluding her from using the semen of a gay friend violated her constitutional rights. A three-judge panel stated that the federal regulation is “rational and health based,” given the “higher prevalence of hiv and hepatitis among men in the msm [men who have had sex with another man] category.”

Lesbians and their gay sperm donor friends have a simple option, of course, and that is to defy the law, either by outright lying about their sexual preferences, or by keeping mum about their personal information. One gay man, Jonathan, a Toronto lawyer involved in a known-donor arrangement, says the fertility clinic he and a lesbian couple went to operated amid a Clintonian aura of don’t-ask, don’t-tell. “They knew full well that I was gay, and that the two women sitting in front of them were a lesbian couple,” he recalls. “They never asked us about anything; we never said anything. It was fine. We worked it out and ended up with a daughter.”

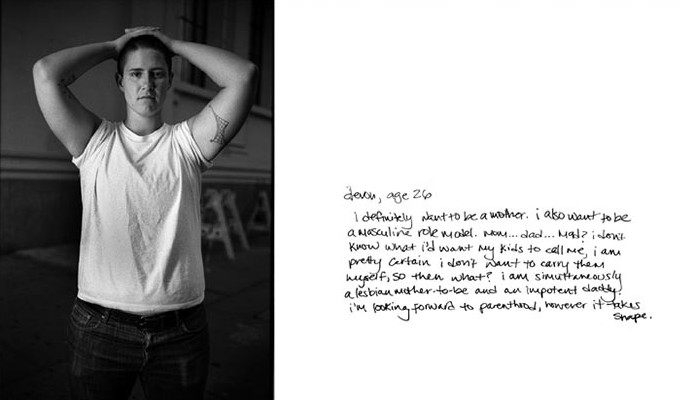

During our interview, Jonathan takes umbrage at my use of the term “donor.” The semantics I’m employing, he points out, have far-reaching social, ethical, and legal implications for all involved. “I find it insulting to be called a donor,” he says. “When we entered this agreement, it was clear that I would be filling a parental role. I’m not a donor; I am a father to my daughter. It all boils down to the role you’ve agreed upon.” Many of the lesbian moms I spoke with argued the opposite, correcting my use of the word “father” and asking that I refer to the gay men involved as “donors.”

This debate over labels has a familiar ring for gays and lesbians; for decades, words like “gay” and “queer” were part of long-winded meditations on how we identified ourselves and were represented by others. Jonathan has reason to be touchy; this fall, he heads into an epic custody battle against the lesbian couple he had his daughter with.

Kelly Jordan confirms that the enforcement of laws and regulations around sperm donation and fertility procedures are haphazard at best, with each clinic operating on its own terms. She points to the fact that although C-13 was passed in 2004, it wasn’t until January of 2006 that the Assisted Human Reproduction Agency of Canada was established. It has wide-ranging duties, including overseeing and enforcing the law, and critics pounced on the appointees to the agency, all of whom were chosen by Prime Minister Harper, and many of them outspoken critics of abortion and ignorant of new fertility treatments—reasons to make lesbian and gay parents nervous.

Because plan B can often be carried out at home, free of institutional interference, some lesbian moms find it very attractive. For Joan and Shauna, another Montreal couple, it seemed a perfect fit. Joan, who was to carry their child, had a close gay friend who had just completed a Ph.D. and was teaching at an American university. Intelligent, handsome, and out of town, Robert was everything they could ask for. And he seemed not to want too much contact beyond a vague godparent role in the child’s life.

What Shauna had not prepared for was the powerful emotional response she would experience whenever Robert was in town and popped by for a visit. “Looking at it from the outside, it seemed really simple,” she says, “but it’s always more complicated than that. Our friends, all enlightened, many queer, still gave our son’s biological parents more weight. They’d say, ‘Did you hear? Joan and Robert had a kid together!’ People in our society are used to a mom and a dad. As the non-biological parent, I was left asking where my place was in all of this.” Being a lesbian mom, Shauna explains, often means coming out all over again. “‘Who’s the father? ’ is a common question,” she says. “With time, it’s getting easier to explain the two-mommy scenario.”

In legal terms, the situation is also evolving very quickly. Jordan says she draws up an increasing number of contracts for lesbian mothers and their known donors. In April of 2007, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that a non-biological lesbian mother could be legally recognized as her son’s third parent. That a court would suggest there could be three legal parents meant contracts had to be altered. Predictably, this sent the self-appointed family values crowd into a frenzy. Ruth Ross of the Christian Legal Fellowship pondered the possibility of a six-parent family in the pages of the National Post.

“From a legal perspective, I would have to recommend that people go with an unknown donor, through a clinic,” says Jordan. She points to a rapidly growing number of cases that pit known donors against lesbian parents. “As it stands, known-donor contracts have not been tested in the courts. My strong advice to people who come to me as they are weighing the options is to go with an unknown donor.”

But Greenbaum says legal advice is only one dimension of this particular decision. “Families are started for a complex set of reasons. What’s most important is that when people enter into these situations, they choose the option they are most comfortable with.” Understandably, lesbian moms tend to feel strongly in favour of the option they selected. “I think that those who choose an anonymous donor are doing that to protect themselves, while those who have a known donor are doing that to benefit the child,” says Joan. “Our choice has had its difficulties, but I’m ultimately glad our son will grow up knowing who his biological father is.”

My friend Suzy found herself caught between prospective plans. “At first, I thought the idea of you being the donor was perfect,” she told me. “We are, after all, pretty much family. But as we continued the home insemination, a sense of doubt set in. I felt I was having a baby with my best friend when I was supposed to be having a child with my wife. That phone call was one of the hardest things I’d ever had to do. But if I really felt that the path we’d chosen was not going to work for us, I felt it imperative to be honest about it.”

Whatever the choice may be, I would like to offer a framework for at least part of this brave new world of parenting. I conclude with some suggestions, culled from first-hand experience, for the etiquette of dumping your sperm donor with grace, dignity, and sensitivity.

Don’t beat around the bush. The person you’re telling will want to know clearly, and as soon as possible, of your decision not to go with him. He can usually sense, quite easily, your avoidance of something so profound.

Work out your specific reasons for opting out and write them down, so your reasoning is consistent. Your now-ex-donor friend deserves a clear explanation.

It may sound surprising, but I think a phone call is the best way to approach the situation (and I don’t mean in a voice mail message). After having hashed out such a discussion, the former donor may want to get off the phone and be alone to process this emotionally charged news.

Finally, I would offer one crucial bit of advice for the ex-donor: don’t take it personally. This may seem almost impossible, but think of the larger issues at hand. What’s most important when planning a family is that the outcome is secure and comfortable for everyone involved.

For the child you’re bringing into this world, that has to remain paramount.