Between 1950 and 1970, as the Arctic was attracting settlers from the south, the Inuit sled dog population plummeted from roughly 10,000 to fewer than 2,000. Many Inuit believe the Royal Canadian Mounted Police slaughtered the dogs to sever Inuit ties to the land, a charge the RCMP denied in a 2006 report. Due to ongoing mistrust, however, the Inuit largely declined to participate in that inquiry. In an attempt to promote reconciliation, a truth commission established by Nunavut’s Qikiqtani Inuit Association in 2007 has heard testimony from more than 500 witnesses—people like Peter Irniq, one of the now ten-year-old territory’s first commissioners; Walter Rudnicki, a social worker with the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources in the ’60s; and Terrence Jenkin, a retired RCMP officer stationed in the North around the same time. As the commission prepares to release its findings, The Walrus shares evidence of a tragic culture clash.

Rudnicki: When my first interpreter moved to what was then Frobisher Bay, she had a small child who was the apple of her eye. The kid was sliding down a hill and slid into a tied-up line of sled dogs, and they made short work of him. He was chewed up and he died. And Paulette shortly after committed suicide. So the dogs were shot. Whether this was good or not, I’m not prepared to say. From one perspective, sled dogs were an important means of transportation. But during the summer, they were neglected frequently, unless they were used for some very specific purpose—breeding or whatever.

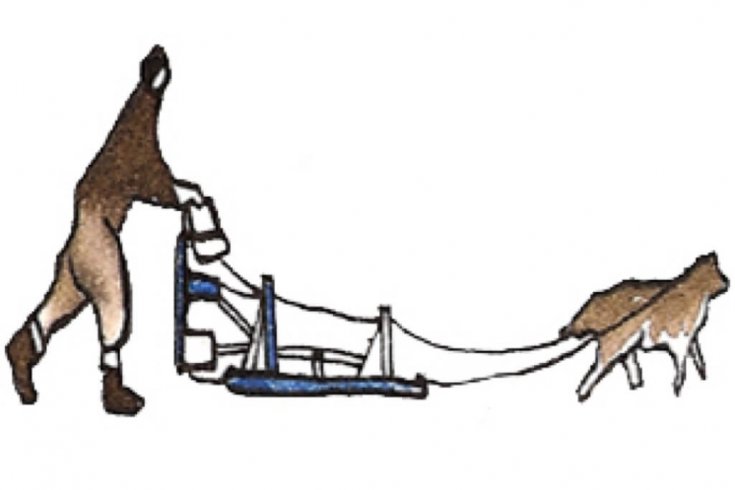

Dog Power

From Jack London’s White Fang

A companionship did exist between White Fang and the other dogs, but it was one of warfare and enmity. He had never learned to play with them. He knew only how to fight, and fight with them he did, returning to them a hundred-fold the snaps and slashes they had given him in the days when Lip-lip was leader of the pack. But Lip-lip was no longer leader—except when he fled away before his mates at the end of his rope, the sled bounding along behind. In camp he kept close to Mit-sah or Grey Beaver or Kloo-kooch. He did not dare venture away from the gods, for now the fangs of all dogs were against him, and he tasted to the dregs the persecution that had been White Fang’s.

Irniq: Let me tell you a bit about our dogs. Our dogs were like your workhorses. We used them for communication. We would put a string around their neck with a little note in Inuktitut syllabics and send them to another camp four or five miles away. Our dogs were used for pulling qamutiik, the sleigh. We used them for tasikuaq, which is a sniffing dog, when we were hunting on sea ice in the wintertime. In the summertime, we used them to carry heavy loads of our belongings on their backs. Our dogs would find their way in the big blizzard when we were going back home, when we couldn’t find ourselves anymore.

Jenkin: There were more dogs running loose as more people came into Iqaluit from the outlying camps. I think that any day you could probably go to the local dump and see forty or fifty or more of these dogs scavenging there. You could also see small packs of dogs running along around the various residential areas. I don’t want to exaggerate. It wasn’t that they were walking underfoot, but they were there.

Irniq: We had a great deal of respect for our Inuit dogs. My father used to say, just before he gave his dogs to me, don’t beat your dogs. If you beat them, they’re going to become very scared, and they’re not going to want to do whatever you want them to do. Our dogs were extremely disciplined as long as they had a good leader. They were not tied up in the community. And they were not scary dogs. When they were scary, pi&&angisaqtut, rabid dogs, we knew.

Jenkin: The Eskimo dog was not a domestic animal. He was not taught restraint. He was taught to obey at the end of a whip. And that was about it. The few occasions where I saw sled dogs treated as pets was when a father or mother would allow her child to have one for a few weeks, but then it would be entered back into the pack. These dogs, too, were never well fed, so they were always hungry. Of course, dogs are always hungry. I have a Lab who’s always hungry, too. But the sled dog was probably willing to go to further extents for food than others.

Rudnicki: My role was to make sure the supplies for the rehab centre and the community were properly delivered and properly used. Walking at night, I passed what was called a “five-twelve house”—512 square feet to house Inuit people. The place was full of sled dogs screaming and yapping and yelling, and I thought, “What the hell is going on? ” I walked in there, which was maybe a silly thing to do, and here were all these dogs into the year’s supply of meat for the community. I didn’t much take to that kind of priority, so I picked up a two-by-four and lashed out at the dogs. They could have made short work of me if they had chosen to do so, but away they went.

Irniq: While I have never seen RCMP actually killing the dogs, in the 1950s and 1960s I heard stories of dog killings from my father and other Inuit hunters in Naujaat Repulse Bay. I am aware that Peter Katorkra, who died a few years ago, was made a dog officer by the RCMP, and he was to kill any loose dogs running around in Naujaat Repulse Bay.

Jenkin: I can’t actually remember personally shooting a dog, with one exception. It was in Pangnirtung. I hadn’t been there very long, but I do recall saying that we were going to enforce the dog ordinance. We were going to control it strictly, and if the dogs couldn’t be caught they would be destroyed. One morning, I heard this large commotion just outside the RCMP residence, and I looked out, and there was a small pack of dogs. It must have been five, six, seven dogs. So I went out and shot the first dog I could. Why I remember is that the Eskimo special constable Joanasie immediately came up to me and said, “That was the police dog.” Of course, I was pretty shocked and had to come back at him, I suppose, and said, “Why is the police dog running loose? ” Well, it happened, and I guess a police dog should be treated like any other dog.

Irniq: If I spoke about what I’m saying today, I would have been severely punished by the Hudson’s Bay Company manager, by the Roman Catholic priest, by the grey nuns in Chesterfield Inlet, and threatened with an arrest by the RCMP. Because we were not supposed to criticize the white man when he came to the Arctic. We were supposed to be obedient people.

Rudnicki: I never heard about any official edict to get rid of the sled dogs. The Inuit were being attracted to the hamlets. Many of them were giving up life on the land. It was their land, but with population increase I guess it was getting more difficult to live on the land in distant camps. People chose to move because their kids were in residential school, or because they had health problems. There was a Hudson’s Bay Company store. There were welfare services. They saw reason to go into these hamlets, and they brought their sled dogs.