After more than two weeks of the longest heat wave Greece has yet recorded, in July 2023, Athens felt as if it were coming apart at the seams.

The streets stank, with garbage collectors instructed not to work during daylight hours for fear of heatstroke. Ordinarily delightful Athenians were snappy and on edge. I saw three fights in a day, having never witnessed one in five previous years of residence there. With the shadeless Acropolis closed by government order and some restaurants shuttered after their uncooled kitchens reached dangerous temperatures, many tourists looked thoroughly miserable, mutinous even, as their much-anticipated holidays soured.

Sweating over a blank Word document in my apartment, I understood how grimly apt this all seemed. Here I was trying to write about climate-induced dysfunction in the West. Now I had rich, highly relevant material on my doorstep. But as my long-suffering air-conditioning unit started to protest, my partner, Katrin, and I made a break for the relative cool of the mountains. Little did we anticipate, as we exited the city, what a tour of Greece’s wider climate woes we would receive along the way.

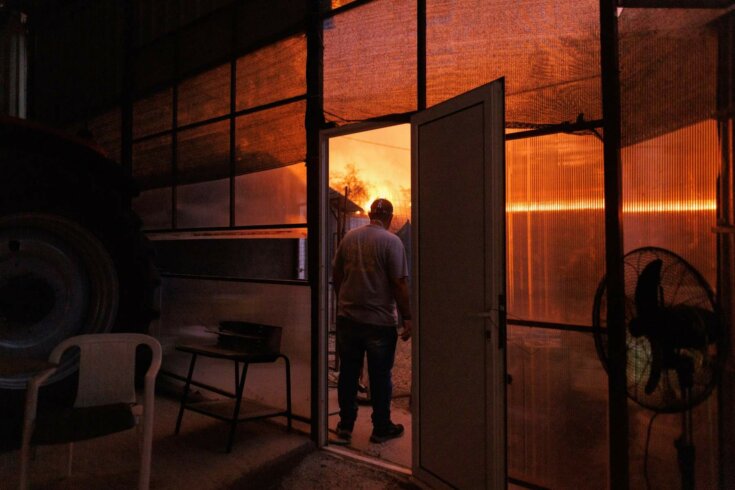

Driving north, we came across our first wildfire, near ancient Thebes, a now largely nondescript town that, like almost everywhere in the country, is nevertheless littered with world-class ruins. Shortly afterward, we encountered another wildfire inside the village of Kato Tithorea. Groups of mostly South Asian farm labourers tried to douse it in the absence of uniformed firefighters, who were badly overstretched combating many of the ninety or so other blazes that had broken out that day.

But with the wind kicking up and the browning vegetation almost asking to burn after a rainless winter, the flames leapt like grasshoppers, from olive grove to greenhouses and across the train tracks, as we watched. In one of those painful ironies, it was the arrival of the summer Meltemi wind that finally snuffed out the heat wave, but that, in so doing, simultaneously fanned the fires into even less containable beasts. By the time we neared Mount Pelion in central Greece, we had not seen a speck of smoke-free sky for several hours.

Even 3,000 feet up on the mountain, a stunning and densely forested massif which curls for almost a hundred miles into the Aegean, the fires loomed large. A huge pall of inky black plumes from the biggest inferno to strike the country shadowed the surrounding sea, forming an incongruous backdrop to an international youth sailing championship—many of whose participants were soon to join an emergency flotilla evacuating locals trapped with their backs against the water.

We watched as the flames enveloped a valley, ultimately killing a disabled woman, whose elderly husband had been unable to carry her to safety, and a shepherd, who died trying to save his flock. Up to 80 percent of all livestock in parts of the province perished. We looked on as the fire ate through industrial areas on the periphery of the city of Volos, releasing chemical-tinged fumes so noxious that we tasted them high up on Pelion.

Locals looked increasingly scared and bewildered. They were also getting angrier. “What about us?” a shopkeeper asked. Most media attention had turned to an even more photogenic mega fire that had flared up concurrently on the heavily touristed island of Rhodes. “Where are the cameras?”

Then came the booms. The first, a faint one, originated in a wine and liquor warehouse, the fire having made a beeline for its barrels of locally brewed brandy. The next few, from a military munitions depot, were of a different magnitude. The noise of exploding bombs and bullets took out windows several miles away and almost knocked me off my feet as I balanced awkwardly on a log trying to tie my laces. Those detonations were followed, over the next hour, by the roar of low-flying F-16s. The Hellenic air force was evacuating billions of dollars’ worth of hardware before the flames got to them. So culminated Cerberus, the most menacing of a crop of newly named heat waves.

But if people had thought that was to be the end of their horror summer, they were to be sadly mistaken. Over the next two months, the country was rattled by additional climate-related disasters, each as or more destructive than the last.

Another massive round of fires culminated in modern Greece’s largest ever, a forest-munching monster along the Turkish border. That blaze killed at least twenty-six undocumented migrants, many of whom were themselves fleeing climate-related disorder elsewhere and had been trekking through the area en route to northern Europe. Though there was no evidence that migrants were responsible for any of the fires, some locals held them culpable and launched “hunting parties” amid online calls for extrajudicial executions.

It slowly began to dawn on people that this was how things are going to be, perhaps from here on out. As my friend Eleni Myrivili, then the chief heat officer of Athens, put it, “We used to look forward to summer. Now it terrifies us.”

This is the story of climate-related violence around the world, and it is already far more common than you might imagine. In large chunks of Africa and Central Asia, climate stresses are fuelling fights between farmers and herders. In the Middle East, South Asia, Latin America, and beyond, these changes are intensifying everything from gang warfare in urban neighbourhoods to old-school piracy in the coastal waters of Bangladesh. Across many of the world’s most vulnerable landscapes, climate change and other environmental furies are merging with other, better-understood destabilizers such as corruption to undermine dozens of countries that can ill afford additional crises.

And that is just the here and the now. As these stresses and shocks come thicker and faster, rapidly changing conditions threaten to apply the kind of pressure that even the richest of places might struggle to withstand.

What we are seeing now is a very different beast, or at least one that is striking in different ways, with more complex ramifications, across a more challenging political landscape. Decades of progressively fiercer warming means that more people have less access to resources, or at least less consistent access to them, while at the same time that they must confront rampant extreme weather–fuelled disasters, such as floods and fires. These cascading risks are merging with other day-to-day challenges to overtax coping mechanisms and worsen poverty.

“In the past, summer was summer, and winter was winter, but now everything’s mixed up,” said Awad Hawran, who grows mangoes, sugarcane, dates, and watermelons on a one-and-a-half-acre plot alongside the Nile in Sudan. “It’s hard to continue farming when even the desert and weather are against you.”

None of that immiseration necessarily leads to violence, but climate change is desperately unequal in its application of pressure. In my experience, troubles are more likely to emerge in places where some people are suffering mightily from climate-related stress, such as farmers or villagers in general, at the same time as others are getting by just fine or even prospering. It is that relative disparity in fortunes and government responses, a mirror of wider inequalities, that, much more than the poverty itself, can drive dangerous degrees of resentment.

“We suffer the most. They get all the help,” I have frequently heard communities and individuals say of another.

Mohammed Atiyeh, a farmer and activist in a dangerously parched part of Jordan, perhaps put it best. “In a country that might run out of water,” he said, “there is regulation only for the weak and poor.” His own crops, already ailing from weak rains and feeble river flow, had been withered by the water hoarding of a politically connected neighbour.

All the while, a half century or more of intense environmental degradation has combined with prolific population growth to maximize the impacts of these stresses. Climate-induced drought is a challenge. Climate-induced drought is significantly more challenging when it strikes communities that are already reeling from pollution, groundwater depletion, and other very “prosaic” ills. In these instances, minor manifestations of climate change can be enough to pitch struggling people into violence—particularly if they feel that corruption or other forms of state action or inaction are hobbling them at their time of greatest need. “Even a mosquito can make a lion’s eye bleed,” an Arab proverb goes.

Vitally, climate change is not playing out in a political vacuum, and the world that spawned it and that is, in turn, now suffering from its fallout is arguably more geopolitically complex than at any time in recent history. The number of armed conflicts of any sort is at its highest since the Cold War, and the number of intrastate conflicts in particular is possibly at its highest since World War II, while the quantity and quality of democracies has wavered badly across the board.

There are more displaced and hungry people now than at any time since 1945. There is more state mismanagement or, more accurately perhaps, there are more complex issues for more states to mismanage. Climate change is stealing into communities where people are already divided, institutions weak and discredited, and officials reviled, and it’s stomping its metaphorical boot on wounds that often need little encouragement to widen or reopen.

We are unhappily used to hearing of chaos and distress of varying kinds in the poorer countries of the world. Those are the parts of the world suffering the worst climate impacts, and those are the ones with much of its shoddiest governance. They are also, owing to the interplay between those two ills, subject to most climate-related violence.

But not just them. The more the West’s weather conditions come to resemble those of its less affluent, generally less climatically temperate peers, the more its degree of peacefulness might too. “Our” own political stability and security may be compromised by climate much more than many of us might have imagined. In fact, they already have been.

A lot of the risk in richer countries depends on climate crises elsewhere—or, more particularly, how authorities in places like Greece respond to them. For one, migration from war-worn Syria transformed Europe’s politics in a more hard-line, exclusionary direction for at least a decade. Climate-related challenges may spur many times more people to try to journey over the Mediterranean.

Similarly, the supply-chain shocks unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have propelled severe inflation across our unprecedentedly interconnected world. Those, too, may pale in comparison with the consequences of failing harvests in major food exporters, the destruction of industry and infrastructure, and disrupted transit through globally significant choke points, such as the intensely climate-vulnerable Panama Canal. As a sign displayed by the Pakistani Pavilion at the COP27 climate conference in Egypt in 2022 stated in bold letters following the floods that inundated up to a third of the country months earlier, “What goes on in Pakistan won’t stay in Pakistan.”

And what of the impact of the green transition on major fossil fuel producers, the largest of which flank or are near Europe’s peripheries (or, in the case of Venezuela, near-ish to the US’s southern border)? If you are Iraq or Algeria, dependent on oil and gas for almost all state revenues, it is a mammoth ask to rework much of your economy while simultaneously navigating severe climate woes—and all without collapsing into an unmanageable mess with consequences likely to be felt near and far. It is tricky to imagine that all parties will be able to pull off this balancing act. To that might be added the rich world’s potential contribution to instability in the poorer world as it pursues the minerals required to decarbonize our economies—and the deals it strikes to keep migrants at bay.

But from within the West as well, we can see the makings of significant climate-related chaos. Europe and the United States already experience more crime during periods of the kind of extreme weather that climate change makes much more likely. Plenty of our own economic sectors, including Mediterranean tourism and coastal American real estate, could take major, possibly existential, hits—to uncertain societal effect. And though the green transition may be an economic boon overall, not to mention an absolute necessity, it will not be possible without generating losers at home.

The fact that those losses are unevenly distributed is already providing rich pickings for demagogic politicians, some of whom are making hay from the loss of identity that can accompany the process—and climate change in general. Omar El Akkad’s American War, a “cli-fi” novel, is premised on the idea that the United States will refuse to ditch fossil fuels, leaving it broken and at the mercy of previously poorer parts of the world that had successfully adapted. That seems highly improbable, but disinformation and foot dragging from vested interests are at least slowing the transition and creating openings for extremists of various stripes.

In this chaotic, potentially more violent world, one might imagine that we will have greater need of militaries. Early evidence certainly seems to bear that out, with troops from scores of nations now called upon to help during natural disasters and security officials girding themselves for extra climate-related challenges.

“I think it’s pretty clear that even modest sea level rise will trouble North America and Europe no end,” said James Woolsey, who directed the Central Intelligence Agency during the Bill Clinton administration, and whose agency played an important and largely unsung role in identifying how swiftly polar ice caps were melting through the 1990s. “It can radically affect the operations of ships, of ports, of air bases. People who don’t get this should read more.”

But for all that demand and perhaps necessity, militaries’ ability to operate in this more complicated environment may be affected too—as seen in Greece with its evacuated air bases and exploding arsenals. About half of all global US military installations have been in some way damaged or affected by extreme weather, the Pentagon said in 2018. Some, such as the world’s largest naval base, at Norfolk, Virginia, are now almost routinely partly submerged, at a cost of many billions of dollars.

Most dangerously, it is unclear what unfamiliar conditions will do to “us”—and by extension our decision making, our behaviour, our hopes, dreams, and fears. Conventional wisdom suggests that wealthier states will withstand these pressures better. It sounds logical enough. We have more money, more state capacity, and, for the time being at least, generally less exposure to the most debilitating climate stresses.

But some scholars question that premise. Popular frustration with government frequently peaks when officials fail to deliver services to which citizens have grown accustomed. If that is the case in the West, we, with our generally strong sense of entitlement, might be in for an awful lot of bother.

Already, people in parts of Europe and North America have experienced the following in recent years: water shortages and bans on hosepipe use in places usually overendowed with drizzle (Belgium and the UK), mainstream churches resurrecting traditional prayers for rain at times of extreme drought (south of France), hospital burn units at capacity with people who have fallen on sun-baked sidewalks (Arizona), wildfires so hot that water from plane dumps evaporates before it strikes the flames (Canada), large numbers of Amazon drivers vomiting from heatstroke while doing their rounds (California), and the much-vaunted re-emergence of the “hunger stones.” “If you see me, cry,” reads one seventeenth-century message placed in Germany’s Elbe River to warn of imminent famine.

As these sorts of shocks become more severe, more common, and afflict more people who, because they have never experienced anything like them, are especially psychologically ill prepared, there is no telling how we will respond. Saleemul Huq, the late great British Bangladeshi champion of climate justice, suggested that it might galvanize us. “Perhaps this will prompt action?” he said, almost to himself over a London coffee. “That’s always been the hope.”

Perhaps. But others have less rosy projections. “It is the people who live in the greatest comfort on record,” philosopher Zygmunt Bauman wrote in 2006, “more cosseted and pampered than any other people in history who feel more threatened, insecure, and frightened, more inclined to panic, and more passionate about everything related to security and safety than people in most other societies, past and present.”

Then there are tensions that could accompany rich countries’ continued failure to help climate-proof poorer ones. The longer the world pursues varying quantities and qualities of climate action, the more vulnerable the West and other major emitters will be to Global South fury. As the many kinds of fallout from climate change come into sharper focus, it could get trickier to quibble with the Global South’s fundamental grievance: that they are suffering most from a problem that is largely of our making and which we in the Global North appear insufficiently willing to help stanch.

There is a reason why the intelligence community in Washington rates fiercer blowback from angry developing countries among the most immediate climate risks to climate security and US interests. “Those who produce the garbage refuse to pay their bills,” said Kenyan president William Ruto in discussion with the UK’s King Charles in 2023, an impression that was likely only furthered by many Western countries’ momentary backtracking on their own fossil fuel phase-outs following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

When climate shocks intensify and their impacts worsen, Western leaders might imagine that afflicted peoples will turn their ire on the underlying source of their troubles—fossil fuels and those responsible for producing and deploying them. If key Western countries were to renege on whatever progress they have so far made toward net zero, there is no telling what effect that might have on North–South relations. Multilateral climate action, already deeply troubled, might breathe its last.

Adapted and excerpted from The Heat and the Fury: On the Frontlines of Climate Violence by Peter Schwartzstein. Copyright © 2024 Peter Schwartzstein. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, DC.