On June 12, 1962, fifty-nine Americans—well-groomed young men in slim ties, and young women wearing tailored skirts or pantsuits, hair in bouffants, poodle cuts, or ponytails—gathered at the United Automobile Workers hall in Port Huron, Michigan, to hammer out a radical new politics. Among the group were a smattering of “red diaper babies,” veterans of the nascent civil rights movement, older trade union activists, and several delegates from the Socialist Party. The majority, however, were university students from middle-class homes in Texas, Michigan, Ohio, New York, Pennsylvania, and Georgia.

The planning committee hailed from a fledgling New York–based movement, Students for a Democratic Society, which operated as a wing of the League for Industrial Democracy. lid was founded in 1905 as the Intercollegiate Socialist Society by the novelist Upton Sinclair (Jack London was its first president), and counted among its early members such notable figures as Clarence Darrow, Walter Lippmann, and John Reed. (The philosopher Sidney Hook and union president Walter Reuther, best known for leading the United Auto Workers out of the afl-cio, would sign up after iss changed its name in 1921.)

W. Eugene Smith/Magnum

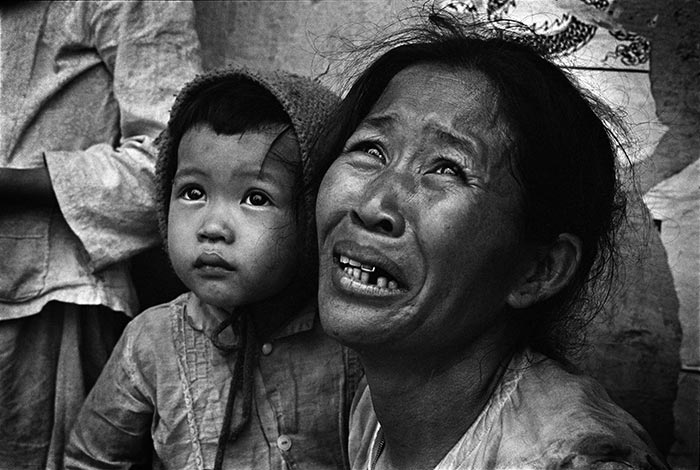

W. Eugene Smith/MagnumPhilip Jones Griffiths/Magnum

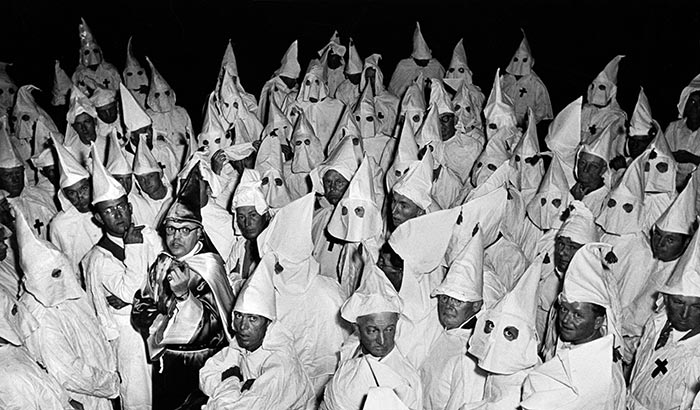

Eve Arnold/Magnum Black and white The Ku Klux Klan holds a rally in North Carolina in 1951; in Hue, Vietnam, a chaplain ministers to a casualty of the war in 1968; protesters carry anti-segregation signs in Virginia in 1960.

Eve Arnold/Magnum Black and white The Ku Klux Klan holds a rally in North Carolina in 1951; in Hue, Vietnam, a chaplain ministers to a casualty of the war in 1968; protesters carry anti-segregation signs in Virginia in 1960.The United States was by no means the first country to experience student unrest. On January 16, 1960, a thousand students occupied Tokyo airport to protest Japanese prime minister Nobusuke Kishi’s decision to sign a security treaty with the US. Three days later in India, forty students protesting the closure of the University of Lucknow were arrested in Delhi. Following the Sharpville massacre in South Africa on March 21, thousands of students around the world rose up against apartheid. In late July, police shot and killed twelve nationalists in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia. On October 17, 1961, students in France joined a demonstration against the country’s continued occupation of Algiers, in which an estimated 200 people were killed.

By comparison, the uprising in America was unimpressive. On February 1, 1960, four African American students staged a sit-in at a whites-only Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Only a handful of white students joined sit-ins in the South, making modest appeals for human rights and desegregation. Few responded to the roll call on March 15, 1960, when the police arrested 350 African Americans for participating in peaceful demonstrations in Orangeburg, South Carolina. At no time did anything even vaguely resembling a nationwide student movement materialize in response to blacks rising up. On the contrary, like the American public and the national media, the white student population for the most part remained on the sidelines.

Frustrated and appalled by what they had begun to think of as pandemic apathy, a few white students joined black activists to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which attempted to remedy the situation by organizing random acts of resistance and creating new forms of civil disobedience. “SNCC later told me…they wanted me to get beat up, because that would get national attention in the media,” recalls Tom Hayden, then an SDS field secretary, but Americans, including university students, would not be moved.

Yet it was not a Japanese, Indian, South African, or French student but twenty-four-year-old Robert Alan Haber, a graduate student at the University of Michigan, who sought to own the spontaneous, restive, sometimes violent expressions of international student unrest. To him and his peers who made the pilgrimage to Port Huron, the opportunity to give the protests an inner coherence and a thematic consistency was too good to miss. At a meeting in Ann Arbor, Haber, who had been elected president of SDS, began downplaying old-world ideologies, treating Saint-Simon’s sentimental socialism, French syndicalism, hardline Marxism, George Bernard Shaw’s Fabianism, Eduard Bernstein’s social democracy, the Jesuit belief that Christ resided in all of us as so much grist for the mill. To the exalted position of the mill itself, Haber raised the New Colossus: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

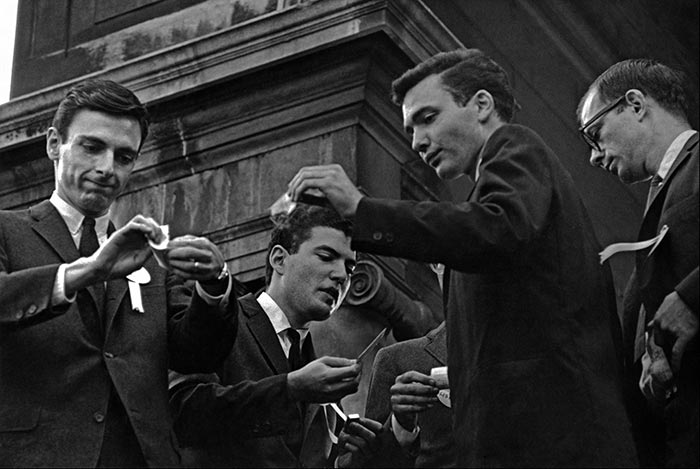

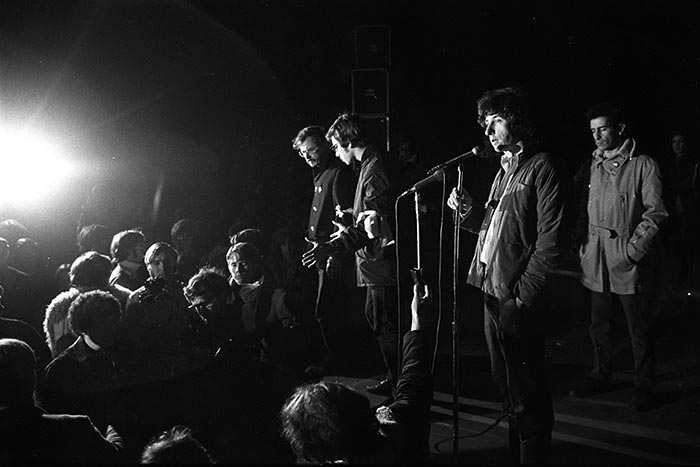

Courtesy of C. Clark Kissinger

Courtesy of C. Clark Kissinger Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum

Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Elliott Erwitt/MagnumRights from wrongs The Students for a Democratic Society meet in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1963; images from Saigon helped to foment anti-war protests; John F. Kennedy in 1961, two years before he sent the civil rights bill to Congress.

Elliott Erwitt/MagnumRights from wrongs The Students for a Democratic Society meet in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1963; images from Saigon helped to foment anti-war protests; John F. Kennedy in 1961, two years before he sent the civil rights bill to Congress.There was something true, if mean spirited, in the criticism of Haber that he saw every student complaint, even if it was only about dormitory food, as fodder for the movement. His hyper-inclusiveness—his indifference to the difference between fire-breathing Communists and soft socialists, between the steely righteousness of Christian soldiers and the pragmatism of mushy liberals, between thoughtful intellectuals and spoiled dorm dwellers—was mind boggling. Yet it was Haber who finally persuaded LID to sponsor the Port Huron gathering, which he immodestly pitched as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to set the “agenda for a generation.”

Haber was hardly a nationalist. His most deeply held values hewed to the concept of humanity and hardly at all to the idea of the nation-state. His commitment to America stemmed mostly from his conviction that for the world to survive, one nation had to take up the torch, experiment, and create new social, political, and economic institutions. His idea that America should step up to the plate had less to do with the vainglory that is American exceptionalism than it did with America’s wealth and power—and with the fact that America was at least half responsible for the Cold War.

Delegates from SNCC responded to Haber’s high-mindedness, as did representatives from Young Christian Students, the National Student Christian Federation, and the Progressive Youth Organizing Committee. But they were a mulish bunch, and the three days and four largely sleepless nights they spent debating questions that singed the wings of Icarus left them hungry, intoxicated, and gasping for air. At the end of the third day, as a new sun dawned over Lake Huron, none of them were prepared to bury their differences. Indeed, they were so incapable of consensus that they decided not to vote on the sixty-three-page draft they had produced, choosing instead to endorse something they called a “living document”—meaning infinitely revisable, not at all conclusive, maybe even rescindable—which came to be known as the “Port Huron Statement.” Mimeographed copies were run over to the Oval Office. Thousands more were sold at campuses across America for twenty-five cents apiece. Two years later, President Lyndon Johnson’s speechwriter, Richard Goodwin, borrowed heavily from the statement’s Values section when he crafted the Great Society speech many Americans still consider Johnson’s finest hour. Twenty-five years later, James Miller, now chair of liberal studies at the New School for Social Research in New York, wrote that the “Port Huron Statement” remains “one of the pivotal documents in post-war American history.”

We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” So the statement began. It could just as well have begun more breathlessly, by citing a spectre, not of Communism but of nuclear Armageddon, which loomed over the earth like the shadow of a giant boot. Indeed, the statement did refer to the invidious cloud—“Our work,” it said, “is guided by the sense that we may be the last generation in the experiment with living”—but it did so in astonishingly subdued tones, very different from the insane modalities expressed by the beat generation. What Port Huron took from Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Lucien Carr, and Neal Cassady was not the madness that overwhelmed the postwar beats. To those who gathered in Port Huron, “Rockland,” Ginsberg’s metaphor for the insane asylum, existed only as the option they abjured. To escape to the asylum seemed even more insane than a world that tolerated the bomb. Worse, it was to refuse responsibility for Little Boy and Fat Man (the atomic bombs the US dropped on Japan), which were, after all, “made in America.”

To the Port Huron gathering, it was America that had lifted the lid, loosed the demons, raised the roof beams, and it was therefore the duty of Americans to restore order. “Universal controlled disarmament must replace deterrence and arms control as the national defense goal.…Experiments in disengagement and demilitarization must be conducted as part of the total disarming process.…The United States’ principal goal should be creating a world where hunger, poverty, disease, ignorance, violence, and exploitation are replaced as central features by abundance, reason, love, and international co-operation.…America should show its commitment to democratic institutions not by withdrawing support from undemocratic regimes, but by making domestic democracy exemplary.…Mechanisms of voluntary association must be created through which political information can be imparted and political participation encouraged.…A full-scale public initiative for civil rights should be undertaken…No Federal co-operation with racism is tolerable…Laws [hastening] school desegregation, voting rights, and economic protection for Negroes are needed right now. The moral force of the Executive Office should be exerted against the Dixiecrats…”

Courtesy of the Peace and Justice Resource Center

Courtesy of the Peace and Justice Resource Center Hiroji Kubota/Magnum

Hiroji Kubota/MagnumBruce Davidson/MagnumSoldier on SDS member Tom Hayden, top right, would go on to craft the “Port Huron Statement”; activists burn their draft cards in New York in 1965; Martin Luther King Jr. marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on March 9, 1965.

The statement’s idealism found favour with the knights of Camelot, the name enchanted Americans gave to President John F. Kennedy’s round table. Recognizing kindred spirits, Kennedy had already established the Peace Corps, in which hundreds of students happily enlisted. Four months after Port Huron, he dispatched hundreds of federal troops to ensure that James Meredith, an African American, gained admission to the University of Mississippi. In May of the following year, he issued National Security Action Memorandum No. 239, ordering a nuclear test ban treaty. In June, he made his famous speech at American University in which, chastened by the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the Cuban Missile Crisis, he described his vision for world peace in an age of nuclear threats. In October, he issued Memorandum No. 263, withdrawing 1,000 military personnel from South Vietnam and promising that “the bulk” of US administrators would be out by the end of 1965. Then, on November 22, he was assassinated.

While Kennedy was gone, the train had already left the station. In July 1964, eleven days after three activists were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, which included a ban on employment discrimination based on sex, race, and religion. (The Southern Dixiecrats, who had controlled the Democratic Party for over a century, abandoned ship—but not politics—regrouping to support Alabama governor George Wallace, who declared in his inaugural speech, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”) The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was redrawn to bring millions of new voters into the system. In 1966, the Freedom of Information Act received congressional approval. In 1967, Colorado legalized abortion in cases of rape, incest, and jeopardy to the mother’s health. Similar laws were later passed in California, North Carolina, and Oregon. In March of 1970, Hawaii became the first state to legalize abortion at the patient’s request. New York followed suit, and that paved the way for Roe v. Wade, which the Supreme Court passed in 1973. The first collective rights for farm workers and public sector employees were negotiated, as were fundamental reforms of university curricula. Anti-sodomy legislation was repealed. Legislation pertaining to homosexual rights was drafted.

But instead of honouring Kennedy’s commitment to defuse the Cold War, Johnson escalated it, often on the sly. He tightened the draft and made it more difficult to dodge. Before long, thousands of young Americans were forced to participate in the unconscionable napalming of Vietnamese villages. The Port Huron reformist movement now morphed into a militant anti-war movement that required but failed to develop a stricter hierarchy and firmer lines of authority. Conservatives, especially in the South, began amassing a counterforce. America was fracturing along old fault lines. In 1963, black civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated. So, later, were Fred Hampton, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy. “We had no idea how much hate there was in America,” says Tom Hayden, who wrote the first draft of the “Port Huron Statement” in a segregated jail cell in Albany, Georgia.

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, deployed strategies he had learned from Joseph McCarthy, casting student unrest as treason, and dispatching undercover agents to infiltrate and sow the seeds of suspicion, resentment, and hate. The CIA fell into lockstep, co-opting the AFL–CIO, the student movement’s natural ally. The war in Indochina expanded to include Cambodia and Laos, and overnight the size of the protest movement doubled and then redoubled. However, Richard Nixon, now president, had signed tough new environmental and consumer protection laws to appease students and workers, and he would not be deterred. As the death toll mounted, rational conversation became impossible. “You had to be against the whole thing,” says Hayden. Students began burning their draft cards, and some even self-immolated. The protest movement collapsed in the smoke and shattered windows of the counter-culture. None of the old SDS leaders could imagine other ways to organize the growing and entirely out-of-control army of hippies and yippies and stoners. Timothy Leary’s beat-like motto, “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” dissolved the last vestiges of idealism.

In 1968, when I was old enough to apply for membership in SDS, Hayden was talking about independent territories from which bands of militant students would lurch, recede, regroup, and strike out. Then, in June 1969, the Progressive Labor Party took over SDS, leaving its remnants to regroup as the paramilitary Weathermen. Operating under the banner “Bring the War Home” and launching a series of “days of rage,” they terrorized America until April 30, 1975, when the war in Vietnam ended with the collapse of Saigon. By then, most everyone who had been involved in the student movement was either in jail, in therapy, hiding at some university, or swimming awkwardly back to the mainstream. The dramatic renewal of democratic spirit that began in Port Huron disappeared. As the “long ’60s” came to an end, so did America’s patience. The people wanted stability restored. A toothy Ronald Reagan agreed.

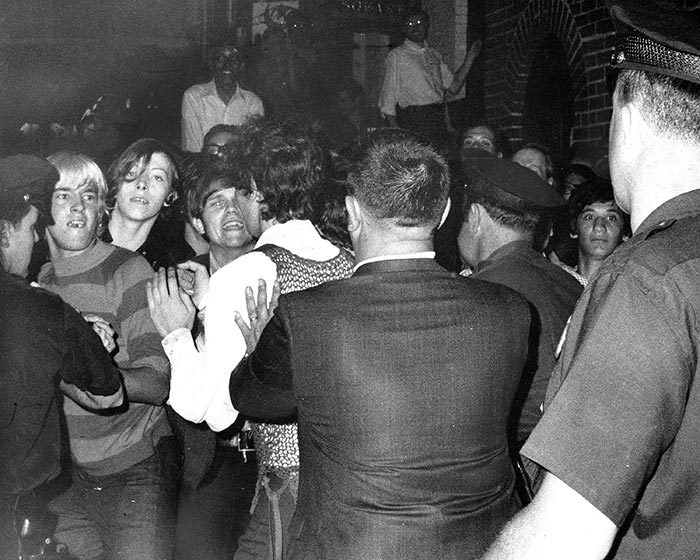

NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images Jay Cassidy/Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Jay Cassidy/Bentley Historical Library, University of MichiganHiroji Kubota/MagnumPride and prejudice Police raid the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York, on June 28, 1969; Hayden addresses the Vietnam Moratorium in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on October 15, 1969; Black Panther Fred Hampton speaks at a meeting in Chicago in 1969.

And then they were back. In January 2010, when everything in the ’60s began to turn fifty, the leaders of the student movement—Al Haber, Tom Hayden, and others—started turning up at conferences, seminars, and public lectures, and in television and radio interviews, raising questions and eyebrows much the way they had when they were young. What, I wondered, were they up to? What had they learned during their long years in exile? What lessons could they impart to writers like Matt Taibbi, who believes that “America never got over the ’60s. The deep social divisions that emerged during that decade remain, for the most part, the divisions that define modern American politics.”

In October 2012, my friend Kenny and I join a stream of young pilgrims making their way to Ann Arbor for a three-day event called A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement in Its Time and Ours. We check in to our hotel close by the University of Michigan and make our way to the Michigan Union, where JFK announced the birth of the Peace Corps. Tonight the speaker is former US senator Tom Hayden. A greybeard resembling Al Haber wearing a tubeteika sits on the auditorium floor, his back against the wall, facing the audience. As we make our way inside, Kenny trips on someone’s leg, prompting two young women in the third row to stand up, smile, and offer us their seats. “You need them more than we do,” the brunette says to Kenny, who argues with her sheepishly. The women tell us we shouldn’t worry, because they have many friends in the overflow area. Kenny and I take their places, feeling our age, and pretty stupid.

A history professor from the university says a few welcoming words, then introduces Hayden, the principal author of the “Port Huron Statement.” He is wearing a cashmere jacket over a blue V-neck sweater over a button-down shirt in a paler blue. He is svelte for seventy-two, his swagger intact, his hair still thick but now grey and slicked back, and he has acquired a beatnik goatee since the ’60s. He leans on the podium and looks up at the projection booth. The lights dim, and Bob Dylan’s voice rings out: “While riding on a train goin’ west.” On the big screen at the front of the hall runs a slide show of yellowed, campy photographs of the movement’s patriarchs: John Dewey, Albert Camus, C. Wright Mills. The audience claps intermittently, respectfully. Kenny, who has no threshold for sentiment, says he feels nauseated, stands up and leaves. A photo of a leaner, bespectacled Al Haber draws fulsome applause. More shots follow of Hayden and others, and finally a recent photograph of the newest SDS chapter in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Hayden tells us this is the seventh or eighth event he has attended in the past year to celebrate the “Port Huron Statement.” He says he is weary, hasn’t slept well for days, and recently visited the site of the UAW hall, which was demolished. “There’s a man standing there, who looks like a California surfer, with his feet in the water, his hair is wild, windblown.…He says to me, ‘I wondered when you were coming.’” Hayden says he thought the man had mistaken him for Jesus Christ. He says he told the man, “You must be John the Baptist.” Then Hayden says to us, the faithful assembled in the Michigan Union auditorium, “And sure enough, he was like this prophetic figure who’s helping us cross from the old world to the new.” Some of the old-timers sitting on the floor near Haber roll their eyes, reminded perhaps of a time when many people were convinced, and none more than Hayden himself, that he was some sort of saviour, but most of the people in the audience are too young to have such recollections. They enjoy the story, laughing out loud.

Hayden does not explain why he seems so obsessed with the ’60s, why he leaves his third wife and young son at home, what he is after—what makes Tom run. “I won’t say [the ’60s] traumatized us,” he says, although in the opening line of his new book, The Long Sixties: From 1960 to Barack Obama, he writes, “The sixties shaped my character permanently.” And is this not what trauma is: an experience that changes a person forever? As he speaks, it becomes clear that, like Taibbi, he is having a hard time getting over the ’60s. The events that transformed him from a brilliant and aimless candidate for the lost generation into a still-brilliant but hardened, suspicious, and sometimes cruel older man, continue to gnaw at his insides. Like so many of his fellow activists, he cannot find a way of stepping back, cannot stop blaming others for bringing the America of the ’60s all too close to civil war. “The lesson I learned,” he says, “was that it was not a crisis of the youth. It was a failure; it was a default of the elders. Had the elders done their job…much of this would have been averted.”

Perhaps it is because he cannot get over the pain, forget the rage, and bury the grudges that he resorts to the pleasures of taxonomy. He is too intent on parsing the decade, trying to fit big, blubbery things like the student movement into little boxes. The spirit was born in a manger, he suggests, and then through no fault of its own became a dark horse and was put down. He mentions the fragmentation but blames it on the CIA. He leaves out his own indiscretions: the disruptive koan for which he became famous; the time he wrongfully accused Abe Peck, a friend of Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, of working for the CIA; the breaks with nearly every other student leader. He does not mention that he was forced out of his commune, moved to Venice, California, changed his name to Emmett Garity, and became an alcoholic. Evidently, he thinks these things are better left unsaid.

“Who wrote the ‘Port Huron Statement? ’” Hayden asks. “I wrote it. I drafted it. I fought the elders and some of my friends to get it even considered at the convention. The convention revised it. They told me to go away and rewrite it again. It was never voted on. That’s why it’s called a living document.” But that leaves out what the other fifty-eight people did. Were they merely, as Hayden suggests, groupies? “They came to own it; they came to possess it.” He pauses, shifts gears, goes into overdrive—as if to prove that he still has the magical touch that earned him a reputation as the supreme moralist of his generation. “This is where I may seem to be leaving my senses,” he says. “I want to argue to you that the ‘Port Huron Statement’ wrote us.” He tries to explain himself, drawing on James Joyce: “We were articulating the unconscious conscience of our generation.…We were in a process of birthing ideas and language that didn’t really exist until the experience itself.”

Howard Ruffner/Life Images/Getty Images

Howard Ruffner/Life Images/Getty Images Burt Glinn/Magnum

Burt Glinn/MagnumDavid Fenton/Getty ImagesThe things they carried The Ohio National Guard opened fire at Kent State on May 4, 1970, killing four protesters; the family attends Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral on June 8, 1968; Weathermen leader Bernardine Dohrn splits from SDS in 1969.

To what spirit is Hayden pointing when he argues that “the ‘Port Huron Statement’ wrote us”? Was it the embryonic spirit of the ’60s? No one who experienced it could deny its existence. It was ubiquitous, omnipresent, immediate, a cyclone lifting everything in its wake, transforming politics, science, journalism, the plastic arts, music. It dictated the way we spoke, how we dressed, the way we grew our hair, hallucinated, and made love—but, as Hayden knows, the ideas that animated the “Port Huron Statement” originated long before. He reminds the audience at the Michigan Union of the several hundred years of revolt against slavery that preceded the ’60s. He reads an excerpt from Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, reflecting on a century of struggle for women’s rights. Unfortunately, he stops short of calling the spirit what it really is: not the spirit of the ’60s, but the spirit of reform.

Calling it the spirit of reform helps us to resist the temptation confronting every generation that experiences it—namely, to imagine that it is all about us and our times; that we are exceptional; that nothing like this has happened before or will ever happen again. To understand how wrong this is, one only need remember the hundreds of thousands who were seized by the spirit during the American, French, and Bolshevik Revolutions. Or one might consider the more recent events in Tahrir Square and, closer to home, in a hundred different encampments launched by the Occupy movement. Seeing it as the spirit of reform rather than of the ’60s allows us to construct a history in which the decade figures as just one of many powerful surges. When was it born? Those comfortable with oral history may go back as far as the year zero, when a young Jewish reformer named Joshua of Nazareth challenged the authority of the rabbinical elders. For those who prefer written history, it probably makes more sense to imagine its conception sometime in the twelfth century, when British barons began whittling away at the legitimacy of Henry I. From either of those distant places, it would not be wrong to leapfrog to the Magna Carta, and from there to that incandescent morning when Martin Luther protested the sale of indulgences.

Any history worth its salt will need to pause in the study of Charles Louis de Secondat, commonly known as Montesquieu, who in the eighteenth century imagined the outlines of an emerging British parliamentary system in terms he called the “trias politica.” Secondat’s work warrants the stop because it inspired the American federalists who fleshed it out, renaming it the system of “checks and balances.” More significant, of course, was the American Revolution itself, because at that moment the spirit of reform, which in Europe was locked in an endless moral struggle aimed at loosening man-made authority, was given a new mandate: to bring the best of the old-world concepts in line with the revolutionary idea of a people’s democracy. Everything needed to be realigned. American intellectuals, writers, and activists rolled up their sleeves and put themselves to work in what may someday be called the Great Realignment, in which the ’60s will have played a large but not decisive role.

The ’60s, after all, failed to mine the full potential of the spirit of democratic reform. The decade did not, for example, reimagine the party system. In his farewell address, George Washington, the first president of the United States, warned that political parties would entrench old hatreds and engender new ones. The party system emerged, not from the Constitution, but from the reformist spirit of the Jacksonian era. But with prescient vision, Washington saw the dangers of partisan politics: the hobbling of government, the shredding of civil society, and destabilization of the economy.

The ’60s also ignored the corrosive influence of institutionalized religion. In the early draft of the “Port Huron Statement,” Hayden tried to put forward an alternative: “We regard Man as infinitely precious and infinitely perfectible,” he declared, as though he were writing the introduction to a new American bible. Mary Varela, who represented the Catholic contingent at Port Huron, argued that Hayden’s words contradicted the doctrine of original sin and would therefore alienate progressive Christians. The assembly agreed and struck the words out. But fifty years later, Hayden is unrepentant. “The ‘Port Huron Statement’ would have been more spiritual had we completed our meetings,” he says. While he could not have written anything that would have persuaded any democratically elected government to restrict an individual’s right to worship as he or she pleased, he could have proposed what the great American sociologist Robert Bellah called America’s civil religion. What would it look like? Would it drop the old-world model of ineluctable authority in favour of something more compatible with the American dream of individual autonomy? Would its rituals perhaps resemble the discussions of everyday moral issues that took place in the ragtag encampments of the Occupy movement?

In his book, Tom Hayden wrote that the spirit of the ’60s is very much alive. This was six months before the birth of the Occupy movement, which, along with reviving the spirit of the ’60s, may herald yet another surge of the spirit of reform. One must resist conceiving of Occupy as a movement concerned only with economic disparity. Think instead of its many splinter groups, including Occupy Faith, the radical assembly that attempted to take over Trinity Church in New York. What unites them, however disparate their origins, are moral concerns. And is their uprising, however uncoordinated, not the moral revolution the authors of the “Port Huron Statement” called for but never completed?

This appeared in the April 2014 issue.