Even before he took office, United States president Donald Trump was talking about annexing Canada, posting on Truth Social in mid-December, “I think it’s a great idea. 51st state!!!” Trump is funny, but only unintentionally, and as his statements have grown more threatening and frequent, even the most optimistic pundits have stopped dismissing them as jokes. The issue of sovereignty has become a unifying cause for Canadians—and the most urgent existential issue of the election.

For Indigenous nations, these threats have a familiar ring. For generations, they have been told that assimilation is in their best interests—by a nation with its hungry gaze fixed on their abundant natural resources, a capricious ally who has shown it will break treaties and agreements when convenient. There is unique potential in this moment for empathy: Canadians might finally be in a position to truly understand why Indigenous people are unwilling to give up their distinct histories, cultures, and identities, no matter the cost of fighting to preserve them.

We want the same things: namely, an ally who respects our treaties and agreements. As Canadians strive to distinguish themselves from Americans—a national pastime infused with new urgency—one way to do so is to demonstrate that this kind of relationship between nations is possible.

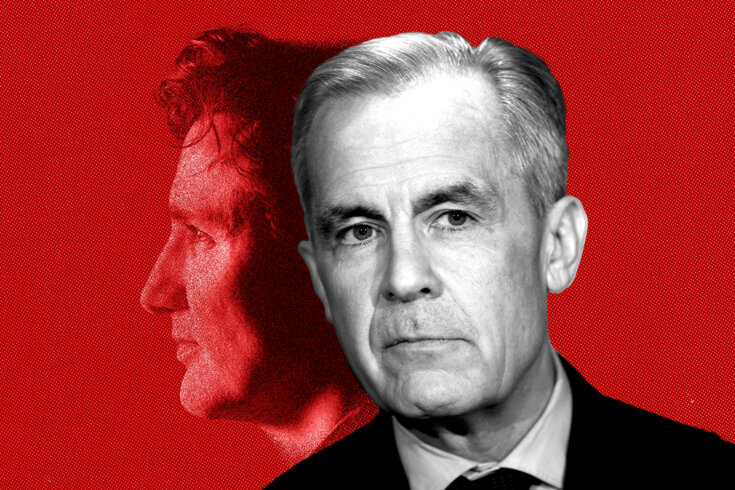

But as Mark Carney and Pierre Poilievre jostle, elbows up, for the job of squaring off against Trump for the next four years, neither has much to say about Indigenous rights and how they fit into this rousing spectacle of nationalism. Besides presenting himself as an alternative to Poilievre and a fresh face for the beleaguered Liberal brand, Carney has been laser-focused on the economy, critical for a nation under threat from its most powerful former ally. He’s said little on Indigenous issues.

Prior to clinching the Liberal leadership race, Carney declined to give an interview or answer questions from APTN News, Canada’s Indigenous national broadcaster—the only candidate to do so, according to the network. His stated commitments to advancing reconciliation sound a lot like Poilievre’s, focusing on economic reconciliation via energy projects. Though members of the New Democratic Party highlighted that Mississauga First Nation had filed a $100 million lawsuit against a subsidiary of Brookfield Asset Management in 2022, while Carney was employed by the firm, Carney has offered nothing as a positive counter narrative.

Carney’s father, Robert, who in the 1960s served as principal of a day school in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories, and later oversaw school programs in the territory, strongly defended the merits of the residential school system and made statements, which have been resurfaced during this election campaign, that reveal his negative views of Indigenous children who had not assimilated. Carney claims not to share those views but has thus far addressed the matter only vaguely, at a recent press conference in Oakville, Ontario, affirming a commitment to “advance [the] process of reconciliation.”

As both candidates promise to expedite projects to bolster Canada’s economy as quickly as possible, neither has said how they would address conflicts with First Nations that do not consent to projects in their territories or those that have concerns. Poilievre, for example, has promised to speed up development in Ontario’s Ring of Fire, despite ongoing opposition from rights-holding First Nations.

If the ethical and legal rationale for upholding Indigenous rights is not sufficiently compelling, the financial ones should be, especially to a “rock-star banker” like Carney. Canada’s legal existence—its claim to the lands, waters, and natural resources that Trump wants to seize—is predicated on treaties signed with First Nations. When those agreements are breached, there are big costs: in 2024, the federal government paid more than $16 billion to settle Indigenous claims, a fraction of the estimated total owed. Forging ahead with resource projects without Indigenous consent and true partnership will only add to that astronomical debt. If Canadians really want a stronger nation, they need a prime minister who treats Indigenous people as more than pipeline shareholders.

Promises of protection and partnership have given way, many times, to greed and impatience. Trust is swiftly destroyed and slowly rebuilt. Indigenous people have no reason to assume Carney shares their interests and values; past Liberal leaders certainly haven’t. “White Paper, 1969,” authored by then minister of Indian affairs and northern development Jean Chretien and then prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, proposed to abolish treaties and assimilate Indigenous people; it was rebuffed by Indigenous leaders, who demanded policy reform instead.

Indigenous nations made progress under former prime minister Justin Trudeau, not all of it with his help. Many of his most significant promises—clean water on reserves, the vast majority of the ninety-four calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the 231 recommendations of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls—remain unfulfilled. Many significant victories for Indigenous people over the past decade have come from fighting Trudeau’s government in court. But he was consistent, at least, in his statements of support for Indigenous rights and reconciliation; they became a key facet of his political identity. For a generation of voters, Trudeau has come to define the values of the Liberal Party, and in regard to his statements of support for Indigenous rights, he was a deviation from the historic norm.

But Carney is working hard to distance himself from Trudeau, whose approval reached a nadir of 22 percent in December, according to the Angus Reid Institute (it has since rebounded, thanks to Trump). The Liberal leader is walking a fine line, attempting to simultaneously galvanize his party and win over deserters from the Conservative Party by axing taxes (carbon, capital gains) and denouncing “the far left.” Where Trudeau was vocal on social justice issues, Carney has carefully avoided any statements that might brand him as “woke”; he has not said anything about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls or the escalating threats against queer and transgender communities, for example, but he did swiftly eliminate the cabinet position for women and gender equality.

As David Moscrop points out, the Liberal Party has survived by changing its values and positions to suit the moment, a strategy that has made it “one of the most successful democratic political parties in world history.” When Trudeau was ascendant, he captured the spirit of a world eager to see social progress and change. We’re living in a different era right now—one in which there is overwhelming resentment from some toward equity, inclusion, Indigenous rights—and Carney, in his taciturn campaigning, is demonstrating that he’s attuned to that shift.

It would be a mistake to neglect Indigenous votes. While First Nations voters comprise just under 3 percent of the population, the Assembly of First Nations has identified thirty-six federal ridings where the margin of victory in the most recent election was smaller than the First Nations population, or where First Nations are at least 10 percent of the electorate. Squamish Nation council chairperson Khelsilem has pointed to the turnout of voters from his nation in the 2017 British Columbia provincial election, which flipped the North Vancouver-Lonsdale riding from the Liberal Party to the NDP. When every riding counts—as it did in 2017 for the BC NDP, and as it will in a federal election unlike any in Canadian history—Indigenous voters could make or break the outcome.

So why not campaign for them? If the goal is to avoid alienating malleable moderate voters, staying silent on Indigenous rights may be part of Carney’s campaign strategy too. There is a growing backlash against reconciliation, most visible in the surge of residential school denialism. In BC—the province where First Nations have arguably won the most significant legal victories for rights recognition, including the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act and the recognition of Haida title—three newly elected MLAs have left the Conservative Party of BC over their grievances against the supposed “reconciliation industry.” Meanwhile, the federal government quietly ended funding for Indigenous communities to search for unmarked graves. Whether intentional or not, through their silence, Carney and Poilievre are sending a loud message about whose votes they care about. Reconciliation is no longer a useful campaign issue.

It’s a shame to see the federal government capitulate to conspiracy theorists and reflexive racism, because political leadership is influential in shaping Canadian attitudes toward Indigenous people. It was in case of Trudeau, and it is in case of Manitoba premier Wab Kinew, who, as a candidate for the premiership, distinguished himself from the incumbent, Heather Stefanson, by campaigning on searching a Winnipeg landfill for the remains of four Indigenous women murdered by serial killer Jeremy Skibicki. Kinew has demonstrated how powerful leadership can be when a politician stands up for Indigenous rights.

The actions and statements of our next prime minister will likewise influence the way Canadians see Indigenous people and issues for at least the next four years. If the polls are correct, Canadians believe that Carney is the best choice to safeguard their rights and build them a better future. It remains to be seen if he offers the same to Indigenous people.