T he Arctic is slipping from Canada’s grasp. Years of neglect—by successive governments and especially under the Liberals—have left our sovereignty in the region vulnerable at precisely the wrong time. As great-power rivalries intensify, climate change opens new shipping routes, and global trade pivots north, our control over the Northwest Passage is becoming more and more tenuous.

In the past two decades, Russia has shifted from symbolic displays of planting subsea flags at the North Pole (in 2007) to hard-power investments in the construction of polar icebreakers. Beginning in 2012, Russian president Vladimir Putin has invested billions toward the construction of seven nuclear-powered icebreakers to gain dominance in a region that was undergoing a transition from an ice-filled domain of isolation to an area of increasing geopolitical competition.

With a displacement of 33,327 tonnes and propulsion power of sixty megawatts, these icebreakers are able to go almost anywhere by breaking up ice up to 2.8 metres thick. The first of this class of new icebreaking colossus was named after the smaller and older icebreaker that helped plant the symbolic seabed flag. The second Arktika went into service in 2020 and was the first of five of the seven icebreakers from this program to enter into service.

In 2018, China released a new Arctic policy declaring itself to be a “near Arctic state.” This was a diplomatic-sounding term that they conjured up in order to demonstrate a serious interest in the region. In a fashion similar to Russia’s, China also began to build a significant capability in icebreaking to back up their symbolic claims to the region. This led to the notion of a “Polar Silk Road” or “Ice Silk Road,” which was an extension of the Belt and Road global ambitions of a China that was building itself up to rival the United States in terms of influence.

These ambitions have quickly become a reality as Canada and the US watched three Chinese icebreakers deployed to the Arctic region this summer at a time when the region was underserviced by North American assets.

Even more troubling is the Arctic’s emergence as a new frontier for geopolitical collaboration among BRICS—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—nations. India and Russia have started to team up on ship building for icebreaking capabilities for both nations, and China has been partnering with Russia on the deployment of icebreakers to maximize use of the Russian-controlled Northeast Passage.

While our geopolitical rivals have been deepening collaboration in the Arctic, Canada has watched our closest ally drift away. During US president Donald Trump’s first term, our sovereignty over the Northwest Passage took a hit when, in 2019, American secretary of state Mike Pompeo called the Canadian assertion of sovereignty in the Northwest Passage “illegitimate.” His comments appeared to be an unprovoked abrogation of the spirit of the 1988 agreement, signed by then prime minister Brian Mulroney and then president Ronald Reagan, with respect to naval transit of the Northwest Passage. This treaty was the natural result of an Arctic defence partnership between the US and Canada that went back to the creation of the Permanent Joint Board of Defence in 1940.

At a time when Canada and the US should have been continuing to operate in close coordination in the north following the Russian buildup and the declaration by China that it was a “near Arctic state,” the US decided to step back and weaken us both. The Pompeo announcement was not only a strategically bad call on the part of our closest ally but it was also the result of Canadian inaction in the Arctic and our overall lack of alignment with the US on policies related to China. We must learn these lessons as we embark on another Trump term.

T o understand the present state of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, you need to look to our history. The Canadian military presence in the Arctic and expressions of our sovereign control over the lands and waterways are entirely the result of the Cold War policies and investments made in the 1940s and ’50s. These investments were made by successive governments of both political stripes. The projects were also often jointly funded and delivered in partnership with the US as part of a strong defence and scientific partnership at the time. Some of our policies in this era were also terribly harmful to Inuit and Indigenous peoples, and we must learn from that experience as we look to invest in the Arctic once again.

The strongest projection of Canadian presence in the high North today is the Canadian Rangers. Created in 1947, the Canadian Rangers became the country’s “eyes” on the ground in a region that represents 40 percent of our land mass. The Rangers leverage Inuit hunters and other Northern residents who hunt and live in the most sparsely populated territory on the North American continent. Today, the Rangers are a 5,000-strong special component of the Canadian Armed Forces Reserves, and they continue to leverage their traditional and modern knowledge of the Arctic to patrol and observe what is happening.

Canadian Forces Station Alert, on the northern part of Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, represents the “ears” of Canada in the high Arctic, as it serves as a signals intelligence outpost. Established in 1950 as part of a joint Canada–US initiative to construct a series of Joint Arctic Weather Stations, Alert is the most northerly permanently inhabited place on the planet. To show the vastness of our country: Alert is actually closer to Moscow than it is to Ottawa. It remains a physical manifestation of Canadian dominion in the high Arctic.

Grise Fjord, the next most northerly populated community after Alert, tells a very different story of Canadian sovereignty operations in the early years of the Cold War and represents another sad chapter in the relationship of Canada with its Indigenous peoples. In 1953, Inuit families were forcibly relocated to Grise Fjord and Resolute Bay (in what is today Nunavut) under the High Arctic Relocation program. These families were transported by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police from their ancestral homes in northern Quebec or on Baffin Island and moved thousands of kilometres away, to the high Arctic.

There were no settlements, no history of hunting or easy access to food sources, and no physical or spiritual connection to the land they were moved to. Hundreds of Inuit people effectively became “human flagpoles” in the drive to demonstrate Canadian sovereignty in the far North.

Successive governments claimed that the relocations were made to offer the families a fresh start from communities that were struggling, but that was never the true reason. Decades after the relocation, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples finally confirmed that the forced move was made in large part to “contribute to the maintenance of Canadian sovereignty.”

It took decades to acknowledge what had happened, and it took almost another two decades for the federal government to apologize and attempt to address the harms of the relocation. In his 2010 apology, then Aboriginal affairs minister John Duncan noted the “extreme hardship and suffering for Inuit who were relocated” and called it a “dark chapter” in Canadian history.

During the Stephen Harper government, of which I was a part, there was more ambition placed on the Arctic than at any time since the government of John Diefenbaker. Prime Minister Harper funded three major initiatives in the North that underscore the importance and complexity of making investments in the region. The government invested in the Road to Tuktoyaktuk, the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, and the naval refuelling station at Nanisivik. These investments had different defence, development, and scientific objectives, but years after the fact, it is clear that they had one thing in common: none of these projects came in on time and on budget due to the extreme complexity of building in the Arctic.

The naval station in Nanisivik is the best example. This project was announced as a naval base in 2007 and planned for a 2015 opening. The project was later downsized into a naval refuelling station, but it has still not been completed. It is now slated for opening sometime this year, which will make it a decade behind schedule. The delays all of these projects experienced underscore the incredible challenge of building infrastructure in the high North.

It also shows that Arctic investments must be adequately planned, funded, and supported on a bipartisan basis. Delivering big projects in the Canadian Arctic will straddle several governments, so we need to make our Northern plans a national, non-partisan example of nation building.

T he Liberal government of Justin Trudeau paid no serious attention to the Arctic in its first two terms, but it was shaken out of its complacency in the third with the full invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022.

After years of underinvestment, Canada moved swiftly on policies meant to bolster our sovereignty in the North. Within a few weeks of the full invasion, they announced a major investment in the North American Aerospace Defense Command, or NORAD, which had been asked for by the Americans for a decade. They also moved swiftly to resolve Canada’s lingering territorial dispute in the Arctic with Denmark. After decades of exchanging friendly bottles of whiskey for schnapps as Canadian or Danish naval crews visited Hans Island, the “whiskey wars” were quickly put aside in the face of Russian aggression.

Trudeau also finally travelled North for the annual Canadian Armed Forces High Arctic exercise known as Operation Nanook, and he brought the secretary general of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization with him. Harper had taken part in this exercise every year, but it had not been a priority for Trudeau. This was a signal that the Canadian government knew the world was radically changing.

Another positive development from the reawakened interest in the Arctic has been the announcement of the Icebreaker Collaboration Effort—ICE—Pact spearheaded by Quebec-based ship builder Chantier Davie. Davie was once at the centre of a major controversy at the beginning of the Trudeau government, in what became known as the Admiral Norman affair, but the shipyard is now helping Canada show strategic ambition to become a global centre of icebreaking excellence.

Davie acquired the Helsinki Shipyards in 2023 and is now leading the Canada–US–Finland ICE Pact for the construction of icebreakers for the three nations to begin to address the Russian tactical advantage in the Arctic. The Liberal government has rightly supported the Davie initiative and is making some much-needed investments to support it.

Weeks after Trump’s re-election and just a month before Trudeau’s resignation, the Liberal government released its highly anticipated Arctic strategy. With Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy, the government indicated the need for a fresh approach to the region. It used the guidepost of “Russia Since 2022” as a section of the policy, which showed that the full invasion of Ukraine was the impetus for the government’s pivot on the Arctic despite the fact that the Russian military buildup in the polar region had been happening over the preceding decade.

The document also curiously used the term “North American Arctic,” which, in the absence of anything new or profoundly important in the policy, led the media to unfairly obsess over this point. Given Pompeo’s language in 2019 and Trump’s re-election, it would have been much more strategic for Canada to focus on the “Canadian Arctic” first before exploring collaboration with the Americans.

There was also less detail in Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy than there was in the two major Arctic sovereignty studies conducted over the past two Parliaments. In my opinion, these reports serve as better policy guides for what Canada needs to do to get serious in the North. I am biased because I helped lead the 2019 study, entitled “Nation-Building at Home, Vigilance Beyond: Preparing for the Coming Decades in the Arctic,” by the Foreign Affairs Committee. In that study, we looked at Russian activity going back to disputes over the sea floor and the construction of icebreakers. We also looked at Chinese advancements in icebreaking capability and the opening of sea lanes in the polar region.

The 2023 report from the Standing Committee on National Defence is an even more timely road map for the rapid action we must take in the Arctic. “A Secure and Sovereign Arctic” recommends many investments and policy changes that need to be made to ensure that Canada can adequately assert our control over the Northwest Passage and project our interests in the region. Recommendations related to submarines and icebreaking capacity are being discussed widely, but one other policy recommendation in this report stands out and deserves further attention.

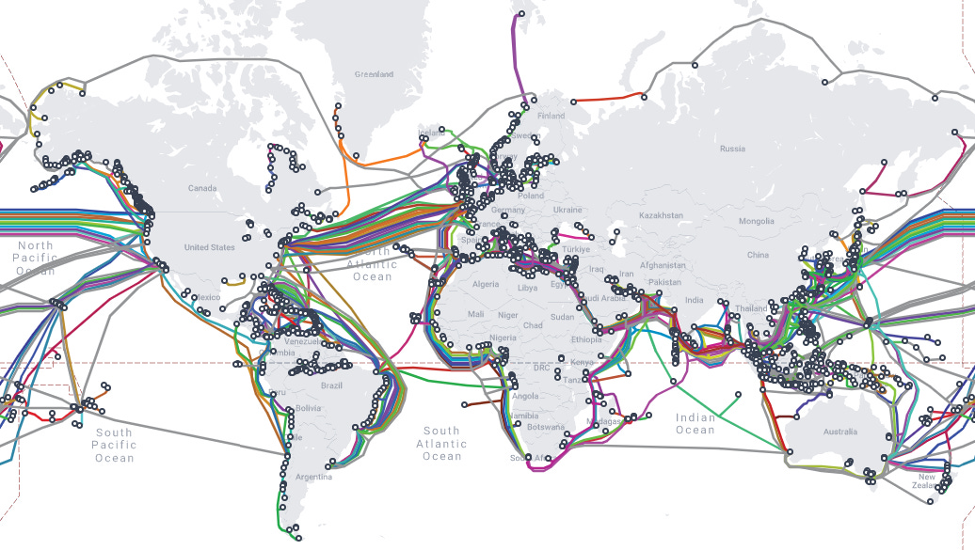

O ne investment that can help assert our sovereignty and reconcile some of the failures of the past in the high North is the installation of subsea cables in our Northwest Passage and across Arctic communities. Recommendation seventeen of “A Secure and Sovereign Arctic” called for Canada to prioritize the installation of subsea fibre optic cables in the Arctic for both the security of the country and the critical connectivity needed by Northern communities. Subsea cables and connectivity would be an excellent example of a “dual-use” investment, where a significant expenditure of public funds achieves multiple objectives in the Arctic.

We have the opportunity to learn lessons from our past and assert our sovereignty today in partnership with Inuit businesses and communities. Grise Fjord and other high Arctic communities remain some of the most isolated places on the planet, and they are once again at the crossroads of geopolitics. With a plan to build out a network of subsea cables, we can connect these remote communities and build a backbone of communications infrastructure to monitor and safeguard our Arctic.

These communities face great challenges and are the most extreme example of the digital divide in Canada. The 2023 auditor general report on rural and remote connectivity confirmed that less than half of Inuit households are connected to the internet.

An Arctic Subsea Sovereignty Cable Network would empower remote communities to engage fully in the digital economy and protect our sovereignty. Linking remote areas with high-speed connectivity will allow Arctic communities to access vital government services related to education or health that other Canadians take for granted.

Subsea cables also have an inherent dual-use capability, because they can connect both military outposts and civilian communities to the internet and both secure and connect the North. When cables are laid in highly strategic waterways like the Northwest Passage, they can also be installed with monitoring equipment that would allow the Canadian government to monitor everything from the impact of climate change to the presence of submarine and surface maritime traffic in our waters.

Current telecommunications in these areas of the high North rely on satellite or microwave transmission, which is costly, prone to environmental and electromagnetic disruptions, and can be geopolitically precarious. Subsea fibre, by contrast, provides a reliable, high-performing, and multi-purpose solution that can connect communities while also securely connecting our military and observational facilities.

Recent controversy around the control of commercial satellite options like Starlink, and the potential vulnerability that an overreliance on just one form of technology, shows the need for sovereign capability in the Arctic. I believe there needs to be both terrestrial and space-based defence and telecommunications systems serving the Arctic, but subsea cables allow for dual-use sovereignty application and meaningful Indigenous-led business partnerships.

T he Americans have been laying thousands of kilometres of subsea cable in their high Alaskan Arctic over the past five years. Canada has installed zero kilometres over this same period. This must change, or the “North American Arctic” envisioned by the Liberal government could slowly become just the American Arctic.

With Trump’s rhetoric about Greenland, this is not an exaggeration, and it may already be happening due to our inaction. At the present time, there is a Finnish American consortium planning to lay subsea cables through the Northwest Passage, but they appear to be planning this without Canadian permission and without Indigenous and Inuit alignment. Sitting idly by and allowing this to happen will erode Canadian claims that the Northwest Passage is an internal Canadian waterway.

If we do not get serious in the Arctic, we will lose it. Building a Canadian Sovereignty Subsea Cable Network will be one way we can reverse this trend, and it represents the most tangible and quick-to-deploy infrastructure investment that can link our Arctic communities and patrol our waterways.

This project could be as transformational for the high North as the railway was for Western Canada over a century ago. At a time when both the Liberals and Conservatives appear to be supporting the NATO goal of spending 2 percent of our gross domestic product on national defence, this dual-use investment can demonstrate our sovereignty today while also addressing some of our failures from the past. It is time for “We the North” to mean more to Canadians than just the playoff slogan for our national basketball team.

Adapted from “Securing the Arctic from the Seabed” by Erin O’Toole (Substack). Reprinted with permission of the author.