It’s hard to pinpoint when exactly Montreal started becoming unaffordable. Like most major social issues, few people initially noticed, until suddenly, everyone did.

Scores of homes were purchased and flipped at inflated rates during the low-interest-rate pandemic buying spree of 2021–2022. Montreal’s Griffintown district, abandoned and dilapidated for decades, now has an abundance of glass condo towers. Young DINKs (dual-income-no-kid couples) walk their dogs along the Lachine Canal.

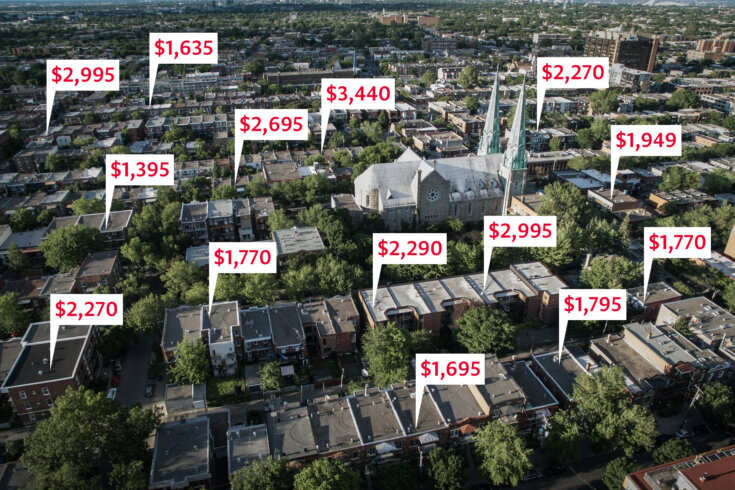

The biggest change has been felt by tenants. Rents are rising fast. People in my Saint-Henri neighbourhood group on Facebook now frantically post messages, asking for any leads on affordable apartments in the area. Anyone daring to ask for a two-bedroom under $1,000 is promptly met with laughter. Renters face the additional challenge of especially scant supply: in Greater Montreal, the overall vacancy rate fell to 1.5 percent in 2023, one of the lowest in twenty years, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Demand is so high that even those with leases aren’t safe. Thanks to ineffective rent control oversight, an explosion of bad-faith schemes by landlords led to a 132 percent increase in forced evictions between 2022 and 2023, as reported by a tenant advocacy group. A recent article by the Rover, on artists being priced out of the city by runaway rents, quoted a local nightlife organizer warning that Montreal—legendary for being grunge, punk, stylish, a rich aesthetic vibe on a bargain—is on track to become “a Toronto that speaks French.”

The province’s right-of-centre Coalition Avenir Québec government has faced criticism for policies seen as favoring landlords and developers over renters. It’s a pressing issue, considering Montreal is fundamentally a city of renters. A 2024 study by the Angus Reid Institute showed it to be the only large city in Canada where more people rent than own a home.

When Premier François Legault made France-Élaine Duranceau—a former real-estate agent—his housing minister in 2022, many worried that things would only get worse for tenants. Sure enough, in June 2023, Duranceau announced Bill 31. While the government presented the legislation as an attempt to “re-establish balance” between renters and landlords, Bill 31 essentially eliminates lease transfers by giving landlords the power to refuse the request for any reason. Lease transfers are a mechanism that kept apartments in Quebec at below market rate for years, sometimes decades, as it allowed tenants to pass on the lower rate to new leaseholders. Ending it will therefore eradicate what little remains of housing security in the province.

After the bill officially became law earlier this year, the province was rocked by demonstrations for months. Protesters refered to Duranceau as the “housing speculation minister” and sweaters were sold depicting her as the former French monarch, Marie Antoinette. An investigation by Ricochet Media also revealed that Duranceau was actively lobbied by her recent business partner, Annie Lemieux, who is the president of a company that owns hundreds of rental units in Quebec. Lemieux also flipped properties with the minister only months before she was elected. Quebec’s ethics commissioner eventually ruled that Duranceau had breached the National Assembly’s code of ethics by fast-tracking a meeting with Lemieux. In another fumble, Duranceau then showed up to inaugurate a social housing project in black Louboutins worth $1,200. The optics of wearing luxury designer shoes while Quebecers scramble to keep a roof over their heads didn’t win her points.

The CAQ government likes to counter criticism by putting the blame for the housing crisis on new immigrants and asylum seekers. While new arrivals may have strained current insufficient housing supplies, they’re not the culprits. If they were, Quebec wouldn’t be experiencing major housing shortages in regions where immigrants are rarely found.

The real problem appears to be CAQ’s reluctance to spend where needed. Alongside the ending of lease transfers, there is an ongoing failure to allocate more funds to affordable housing: a fact decried by a coalition of Quebec non-profits, who say that only 4,000 housing units have been built out of the 14,000 originally promised by the government. Earlier this year, according to the CBC, Montreal mayor Valérie Plante called Legault’s commitment to building social housing—government subsidized dwellings made available to people with low incomes—“vastly insufficient,” accusing CAQ of “making a choice to ignore the housing crisis.” Even the Quebec Landlords Association criticized CAQ’s budget for not providing enough incentives to “stimulate construction.”

But building affordable housing for future use is one thing, keeping people currently housed is another. The Trudeau administration seems to have leapt into action with the creation of a “Canadian Renters’ Bill of Rights,” which would require landlords to disclose their properties’ rental price history to prospective tenants, thus empowering tenants to negotiate fairly. Housing policy expert Steve Pomeroy told CBC that “[I] don’t think, in practical terms, that [the bill of rights] can really be implemented in a way that’s going to have a meaningful impact on rental affordability.” Knowing what a previous tenant paid, argues Pomeroy, won’t necessarily increase tenant bargaining power in a tight rental market. It’s also unclear how much reach the federal government has over housing, when provinces dictate how it is developed and managed. (And indeed, CAQ has already denounced the measure as meddling and an invasion of Quebec’s jurisdiction. “The answer is simple, it’s no,” said one minister.)

But CAQ is paying attention. In a move one opposition member called “a public relations venture to rehabilitate Minister Duranceau’s image,” the government will now ban certain kinds of evictions for the next three years, protecting more senior renters from the practice. It’s a major change of direction for the government, and a welcome one. But an eviction moratorium does little to answer the larger problem: that renters have no real rights and stability and are at the whim of landlords and policy. Nor will it do much to slow gentrification. Montreal’s role as a multilingual cultural hub—attracting talent from across the country and around the world in music, theatre, literature, dance, and even the videogame industry—has been due, in large part, to its lower cost of living. And stopping evictions won’t safeguard that.

What might help is reframing housing as a human right and not just a commodity—as well as elected officials willing to recognize it as such. This shift demands bold policies: rent controls, more affordable homes, and strong tenant protections. Trudeau’s Liberals appear to have made one ambitious step toward this, with a series of large-scale commitments in the form of a 28-page housing plan geared, in part, to “make the playing field fairer for renters.” While Canada signed a United Nations treaty affirming housing as key to the well-being and dignity of every person, most provincial governments refused to even acknowledge it. And Duranceau? She ghosted the reporter who dared ask the question.