In one of many hysterical vignettes collaged in Johnny Would You Love Me if My Dick Were Bigger, a 2015 not-quite-memoir by the writer-artist-dancer-musician Brontez Purnell, our hero, a Black gay American waiter bored at work, anatomizes his discontents with dating another writer. “We differed and disagreed stylistically,” starts Purnell, because “he felt like I was too often sincere and forthcoming in my writing, and I thought he was too often full of shit.”

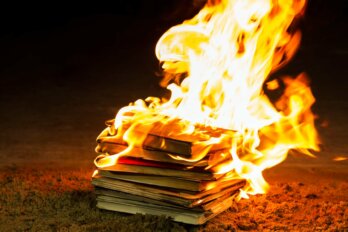

The Boyfriend is always publishing stories about the “Incredible Adventures of Two Boring-Ass White Dudes in Love,” mostly in periodicals under titles like “New Best Gay Erotic Fiction.” The “Brontez” of the novel is aggrieved by the “plucky, wide-eyedness” of it all—“Like, why couldn’t one of the precious boys be a murderer and a junkie or have an eating disorder?” he wonders. Just a few sentences later, he learns his beloved has plagiarized one of his ideas, which tend to slant toward “real shit” like gun violence and semen addiction; infuriated, he drenches his paramour’s silver laptop with lighter fluid (“holy water”) and sets it ablaze in the garden. “He never talked to me ever again,” says Brontez, “and he could never really return the favor: My stories were already on fire.”

Stories written by the real-life Brontez Purnell burn with a rare, frantic blend of humour and sincerity, lyricism and lewdness, desire and disgust. They’re vulgar, brisk, hilariously “autobiographical” works of anti-self-improvement. Typically, Purnell’s narratives eschew the conventions of plot (the only true climaxes happen on worn-out mattresses in airless, too-small rooms). His books are populated with unforgettable characters, often colourfully sketched in just a few fleeting lines: a volatile stepfather who wordlessly polishes his guns after arguments, an elderly trans woman in full gold lamé clinging to a tree trunk on the sidewalk, a satanist who offers Magic: The Gathering tutorials and whose “stroke game was at about 58 percent.”

A born performer, Purnell writes with an eye toward confession and entertainment. This has perhaps never been more true than in Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt, his latest book of spry, freewheeling poems that split the difference between comedy and tragedy, pleasure and pain. Ten Bridges seems to function as a warped self-portrait of its author, chronicling the internal and external dramas of Purnell’s itinerant life as a gay Black man for whom danger is always imminent. The unifying tone here is playful and jocular, but occasionally, that “real shit” intrudes on the frame and threatens to nullify the fun: “But my contempt stands / as does somewhat of a worse fear: / that nobody wants my body / but everyone wants my soul,” Purnell writes.

Purnell is always thrilling and totally unpredictable, so that reading him is like sitting across from a stoned, beloved friend who, at some ungodly hour, after you’ve both arrived home following a long night of debauchery, might casually toss off some eruption of brilliance that unexpectedly rewires your brain. “My only desire is to be desired,” says one of his characters in 100 Boyfriends, his excellent novel in stories, which won the 2022 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction. Even in analyzing the more tenebrous corners of his own pulsing mind—his fetishes and anxieties and greatest fears—Purnell seems hell-bent on writing against the so-called trauma plot. He’s never courting sympathy. His levity and humour convey not a lack of seriousness or criticality but a determination at setting his own terms of engagement, amending the boundaries of what may be defined as scandalous and refusing the audience’s appetite for a lesson to be found in one’s (Black) suffering. Therapy sessions, despite the analyst’s leading questions about absent fathers and sexual abuse, conclude without revelation. (“So boring!”)

Lately, a common pose among literary critics is to express anguish over the alleged wet-eyed sentimentalism of contemporary gay fiction. It’s like all the writers have succumbed to the diagnosis in Johnny Would You Love Me, when “Brontez” scoffs at the Boyfriend’s sexless, humourless stories.

A 2020 essay in Granta, for example, asked readers, “Whatever Happened to Queer Happiness?,” citing authors Hanya Yanagihara, Édouard Louis, and Justin Torres, among others, as proponents of the idea that “to be gay is to be defined by suffering.” This assessment rests on frustration with how these writers tend to render the experiences of their brutalized characters: an unnamed gay teenager interns at a psych ward for lashing out at his family (We the Animals), a “girlish” young man’s rural French childhood is marked by constant violence (The End of Eddy), four classmates struggle through addiction, sexual trauma, physical abuse, and self-harm (A Little Life). The Granta essay takes aim at the misery that forms the weather of these novels, arriving at the conclusion that “in the work of a new generation of writers, queerness seemed only allowed to enter that mainstream so long as it was confessed as being the source of every bad thing in one’s life.”

The following year, a writer for Gawker criticized the “weepy disclosure and self-serious sentimentality” of authors Garth Greenwell, Ocean Vuong, and Douglas Stuart, lamenting their “flattened emotional landscape[s], in which humor has been extinguished, the cacophony of possible affective responses to duress and sadness silenced.” A similar sentiment about “the serious and bleak” opened a 2022 piece in The Yale Review, and a 2023 essay in The Baffler referenced the “strained melodrama and mawkish sentimentality that have become hallmarks of contemporary American gay fiction.”

My personal feelings about those novelists aside, I’m not too sure of the value in berating artists for responding to an extravagantly depressing world with extravagantly depressive art. But it does feel true that much of contemporary gay fiction seems to exist in a dystopic, rain-soaked universe where laughter has been all but outlawed and everyone secretly hates each other. There are open wounds in the work of Purnell, to be sure, but victimhood is hardly a subject of infatuation or sustained interest, nor do his characters quite scan as the “vivified DSM entries” that Parul Sehgal identifies in “The Case Against the Trauma Plot.” Whatever stories of trauma and loss he tells are counterposed with such riotous laughter that even the bleakest memory accumulates a patina of gracious banality.

Purnell knows that life is long, and hard, maybe for no big reason at all, which is what makes it so ridiculous and absurd. Connection seems to be the only worthwhile endeavour. Across his oeuvre, his narrators—lovably dysfunctional, often unsober Black men—frequent gym showers, public bathrooms, bathhouses, and churches, where they’re always in search of sex, which is to say companionship, which is to say intimacy. No subject is too taboo, no detail overly embarrassing, because he has emancipated his men, and his readers, and himself, from the tyranny of shame. Sincerity never calcifies into sentimentalism. When his father tells him, or rather the “him” of the poem “Guy-o-logical Clock: Ticking,” that Brontez was “born doomed,” his apt response is as follows: “honestly, ‘doomed’ is just an easier place to operate from / My willful optimism has always operated on the belief that the show must go on.”

The crackling, confessional poems in Ten Bridges take up many of the subjects (Blackness and masculinity, capitalism and cruising, aging and desirability, mommy issues, daddy issues) that have come to define Purnell’s artistic sensibility, which is, ultimately, that of an incurable emotional exhibitionist. It tracks, then, that Purnell comes from a line of blues singers. Reading his work often brings to mind Ralph Ellison’s 1945 essay on Richard Wright, where he noted: “As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.”

The “memoir in verse” phrase that appends Ten Bridges’ title, however, winks with a trickster’s irony: everyone knows the point of memoir is to lie, that fiction contains as much truth as any honest or dishonest life, and Purnell is attuned to the ways marginalized writers in particular are taken more seriously when it’s clear that they’re testifying as opposed to inventing from scratch. There’s a reflection on graduating from UC Berkeley in “the summer of ’88,” for example, and while Purnell does have an MFA in art practice from Berkeley, his mother did not give birth to him until 1982. Similarly, the inaugural poem, “Oath of Athenian Youth,” undercuts the reader’s autobiographical assumptions, invoking the ancient city just to explode its romantic connotations:

I was born in Athens (Alabama)

this tells you nothing, but I will try.

Though it’s named after

that great city

of antiquity

I know nothing of olive trees and oracles

only cotton stalks

and rivers poisoned with DDT.

It might be true that Purnell was born in Athens, Alabama, but the information available about him online suggests he was in fact born in Triana, Alabama, population 3,000, and that he moved to Oakland at nineteen with a group of white punks his parents took for devil worshippers. When he got there, he immediately started working on Fag School, his punk zine answer to Seventeen magazine, the first issue of which featured handwritten porn reviews, an article about “The Life of a Totally FAB GO-GO BOY!,” and a comic panel of Purnell having sex with his bandmate. Sex, vividly rendered, permeates his writing, but often it’s less sensual than it is scatological, more concerned with the ways an orgasm can be funny, or anticlimactic, or, at the very least, a fine way to get to know someone. Are we ever more ourselves than when we’re naked and supine and telling one another what we want?

It’s difficult to locate Purnell and his irreverence in any obvious literary canon. He seems, to me at least, unclassifiable. He has name-checked writers Mike Albo and Michelle Tea as influences, as well as the punk singer Kathleen Hanna and the Canadian film director Bruce LaBruce, but the sheer breadth of the disciplines his artistry encompasses (film, music, dance, poetry, fiction, performance art) seems to place him in his own lane.

Purnell, who was raised a Christian, refers to himself as the “bard of the underloved and overlooked,” and the intelligence that governs his books is thusly defined by an interest in redeeming the allegedly dishonourable. Junkies, thieves, alcoholics, clinical sex addicts, ex-lovers who are “5’6, demonically aerobicized”—everyone has their wings here. His men often describe themselves as “willfully nonjudgmental”; everyone comes (ha, ha) as they are. “One thing I can truly say I love about myself is that I’m too sketch to lead a moral campaign against anybody,” says one man in 100 Boyfriends. “Also, leading a moral campaign against anything just seemed like a lot of work and I was stoned.”

Across Ten Bridges, Purnell dances across the page like a hyperactive ballerina, delivering jokes and gut punches alike within the space of a couple of lines. Still, there’s no deficit of melancholia or loneliness either. In “Daddy,” he recalls the “Lost Boys” of his twenties, when he finds their faces immortalized behind the screen in old porn videos, “the ones I fathered / and the ones who fathered me,” and is reminded, hopped up on amphetamines, “that most of the stars we see in the sky / are presumably dead / before their light reaches us.” These vistas into the past remind us of a whole generation claimed by HIV/AIDS, and remind us that Purnell’s unmatched levity was not easily achieved. “Saturday Day Night Blues” concludes with a recognition of the metaphor he is becoming in the eyes of other people:

The most high-risk

homosexual behaviour

I engage in

is

simply existing

These poems spill down the page at breakneck pace, and before you know it, you’ve ended up somewhere totally unpredictable and are feeling profoundly moved. In “TOMMY CHIN,” he attends an artists’ luncheon where he gets into a fist fight with the titular poet, who venomously criticized the integrity of his work in a newsletter. Furiously, Purnell attends to the alienating conventions of “experimental literature,” complaining that “if I am not writing / like someone’s favorite dead white man / or even more insultingly / like someone’s white-ass boyfriend,” he is treated as though he has no real command of language.

The poem culminates with him smashing a glass pitcher over Tommy’s head and being banned from the San Francisco Young Gay Poets Luncheon forever. He wears the punishment like a gleaming badge of honour: “but in my defense,” he writes, “I just had to signify / that poetry / is still dangerous.”