It was the early 2000s, and Frankie Perez was living in Queens, New York, crammed into his grandmother’s home with about a dozen members of his extended family. He was twelve or thirteen and had seen the inside of an airplane just a few times, always to visit family in the Dominican Republic. One spring afternoon, an older boy, a neighbour from across the street whom Perez looked up to, introduced him to the thing that would eventually, once he got the hang of it, put him on more planes than he could count: breaking. “That day, all of my cousins and I started breaking, right on our block,” Perez says. “We would lay down some cardboard on the concrete, right in front of our stoop, and that’s where we learned some of the generic breaking moves.”

By the 2000s, hip hop, freshly emerged from its supposed golden age, had bled outside the lines of its musical form to influence basically everything else, from fashion to visual art to television. New programs like America’s Got Talent, So You Think You Can Dance, and America’s Best Dance Crew seemed to exhume from history’s basement an artform Perez says some viewers likely thought had died in the late 1980s, around the time rap became the mainstream expression of hip hop. “If you ask the average person on the street about breaking,” Perez says, “they’ll probably think about it as a fad—as something that used to happen.” (And it is called breaking: breakdancing is a catchall term invented by journalists who, in their early reporting on the scene, used it to incorrectly group together disparate forms of street dance.) But those who know better know that breaking never left the sun-beaten streets or humid subway stations, that it was a global phenomenon long before it was approved for the 2024 Olympic Games, in Paris.

After he discovered breaking, Perez quickly became swept up in New York’s circuit of open practices, competitive jams, and lively cyphers, where dancers form circles—in subway stations, on street corners, in living rooms—and, one after another, enter the middle and show off. On weekends and late weeknights, he would board the underground with a crew of neighbourhood kids around his age and take the train to various boroughs to compete in tournaments by battling other dancers, including in the Bronx, where the subculture was born. To watch a competition is sometimes like watching a fight, which makes sense because some moves are thought to be influenced by martial arts—as well as by gymnastics, uprock, acrobatics, lindy hop, disco, and more. Eventually, Perez got good, then better, and the more established crews in New York began taking notice. He joined the Supreme Beingz, a world-renowned crew, and has danced with them for nearly twelve years.

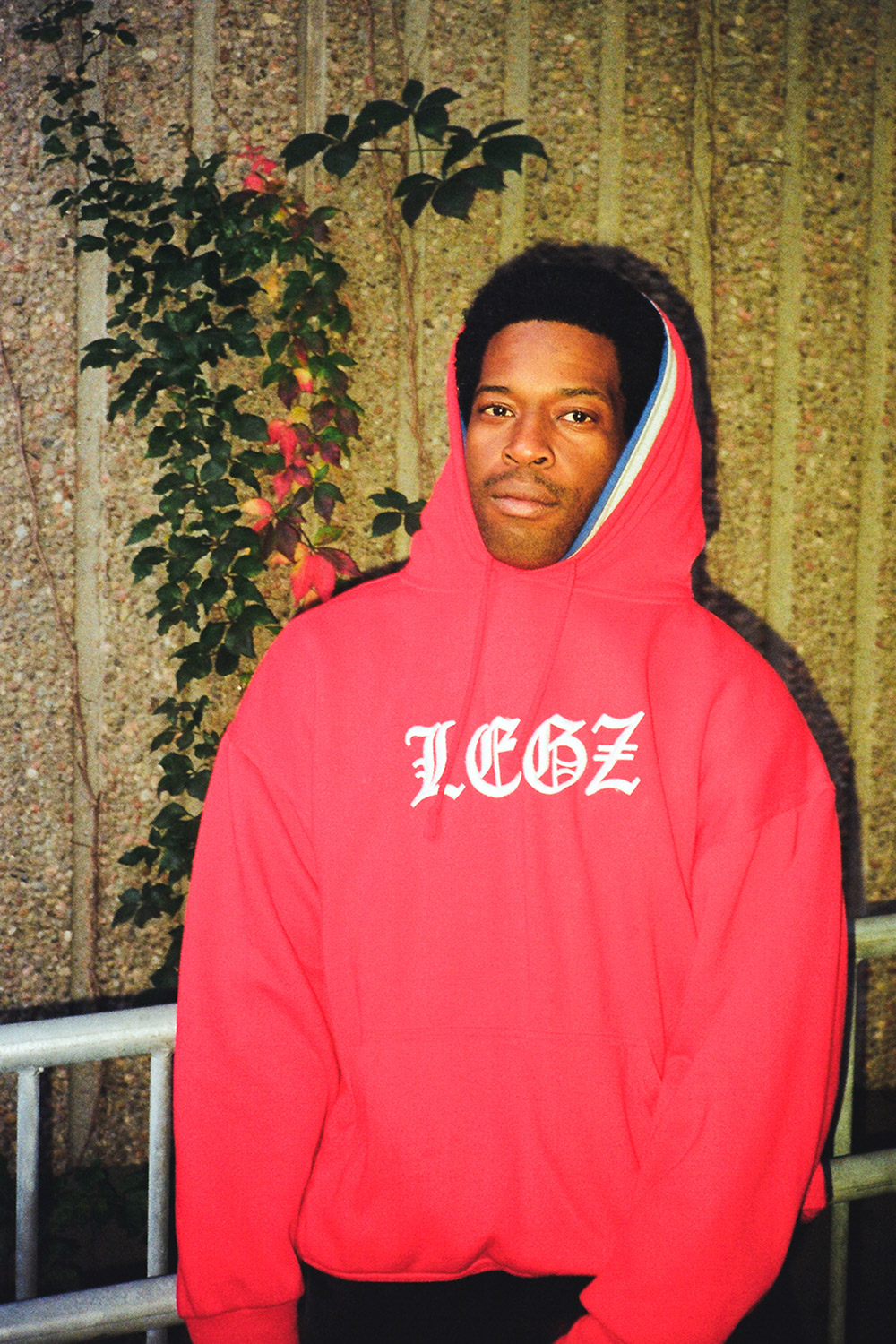

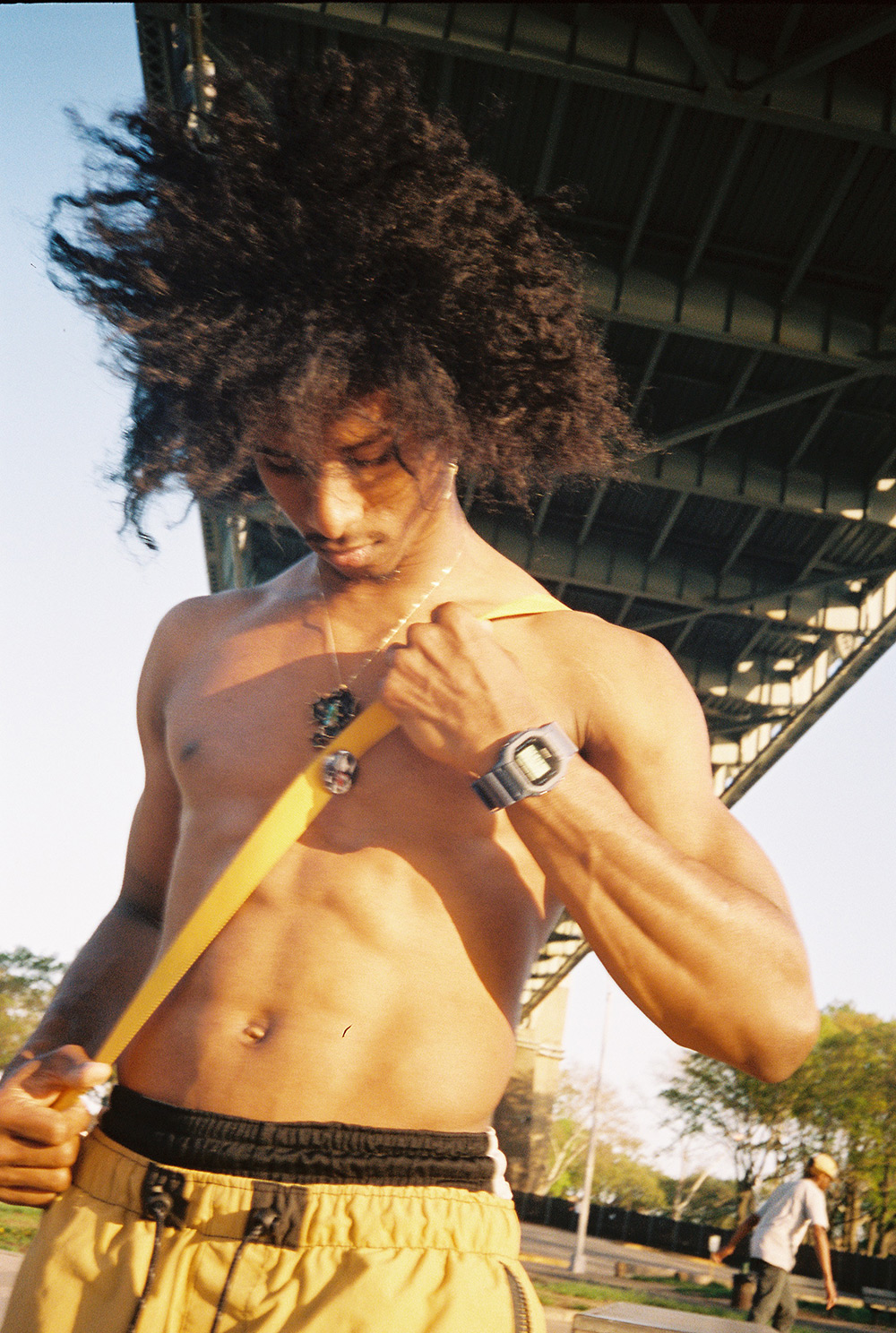

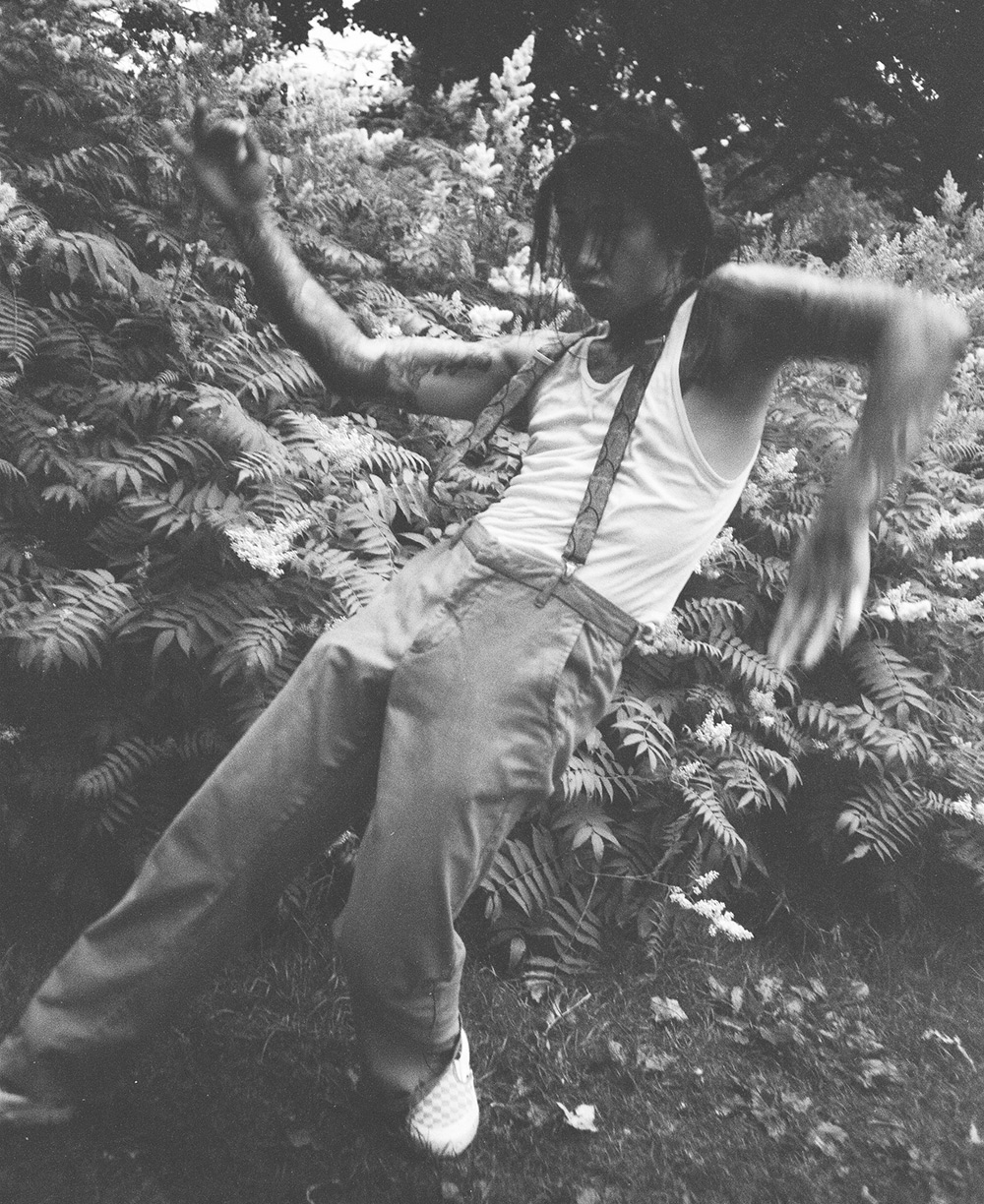

“Since breaking and dance is all around me,” says Perez, now thirty-two and splitting his time between New York and Montreal, where he lives with his wife and son, “it was natural to make a body of work that was about that.” He noticed the surge of attention stemming from certain YouTube channels that occasionally spotlighted b-boys and b-girls (once called break-boys and break-girls), so he borrowed a camera as a tactical gambit of self-promotion. His intention was only to film himself breaking, but he began to develop a love of photographing the people drifting about his world and capturing, with a participant’s eye, the subculture’s frenetic creative energy. Men fly in his photographs. Earthbound dancers contort their bodies into strange muscular forms, as though in a heated argument against gravity. In his photographs, Perez redraws the body’s supposed physical limits, conveying, on one hand, the sheer athleticism of the dance and, on the other, its artistic beauty.

Perez considers many of these pictures—the majority of which were taken in New York and Montreal and are included in his recent book, See Me Up? It’s ’Cause I’ve Been Down—to be documentary in spirit, an affectionate means of archiving a world he believes is often misunderstood and misrepresented. He is drawn to photographing people he feels are largely ignored in popular representations of the subculture: street hitters, the buskers of the community; dancers with physical disabilities; parents whose children watch as they bend themselves into weird shapes. He has noticed a common thread of sensationalism in depictions of breaking, as in ads featuring flashy power moves from models who may not really be b-boys or in films like Battle of the Year, which feature storylines without any clear logic. He thinks of his portraits as an “authentic frame of reference,” a sort of anthropological approach from an insider. One could say that Perez is working to historicize breaking. “I felt like there was a void in the recent photography,” he says, “and that there hasn’t been a contemporary body of work that authentically captures what the scene looks like today.” Back in the ’70s and ’80s, New York photographers like Joe Conzo, Martha Cooper, Ricky Flores, and Jamel Shabazz took as their subjects a dynamic hip hop scene still in its infancy. Since then, the culture has broadened. The style has become more complex. The music has changed. And there are few photographers capturing the new spirit of the old form.

Every expression of hip hop, from graffiti to rap to breaking, is a way for the disenfranchised to be seen, a tape deck recording and rearticulating each and every instance of a city’s failures to recognize the humanity and meet the basic needs of its marginalized members. Breaking was invented by Black and Puerto Rican communities in the crucible of a bankrupt New York whose mayor cut social services and lost control of the city. The essence of hip hop culture is to illuminate the roughness and entropy of the urban American life from which it sprang: a city where homelessness was on the rise, millions of dollars were being poured into the war on drugs, and landlords were torching their apartments so they could claim the insurance money.

If the dance looks chaotic or militant, that’s because it bloomed in a warzone. Breaking is yet another arena in which Black and Brown people have wrung art from tragedy, building moated kingdoms in which to affirm and celebrate one another. The culture has since lost some of its political edge, as all art forms do the further they get from their roots and the more commercialized they become, but Perez is a stenographer of its present moods and attitudes who still conveys its warm sense of community.

Some issues, though, have remained. “There are a lot of people, throughout history, in our culture, who were the best of the best but had to quit earlier and aren’t dancing anymore because the responsibilities of life kicked in and there was no infrastructure for them to support themselves on breaking alone,” Perez says. Since its inception in the late 1970s, breaking has followed a patient odyssey toward the front of the public imagination, a journey that appears to be culminating in its inclusion at the Olympics. Perez’s dream is that the games, which he hopes to compete in, will bring a newfound visibility to the culture and herald more opportunities for b-boys and b-girls struggling, as ever, to convert passions into careers. “We’re in this unique position where we should be able to take advantage of what we do as artist-athletes,” Perez says. “LeBron James can’t say he’s an artist like Kanye West, and Kanye West can’t say he’s an athlete like LeBron James. But I can say that what I do is art and sport, and I want us to be able to take advantage of that space.”

Perez brings to mind a scene near the end of Style Wars, a 1983 documentary about hip-hop culture in which a group of young b-boys is asked what it means to be “professional.” “Getting paid for what you do,” one answers. Another adds, “Doing it for a long time.”