The word trampoline conjures up images of children bouncing around netted cages at birthday parties and barbecues. But a trampoline is also an instrument of flight, and at this summer’s Pan Am Games it will provide Canada with one of its best shots at gold.

Skyriders Trampoline Place, where elite gymnasts regularly train, occupies a nondescript industrial plaza in Richmond Hill, thirty minutes north of downtown Toronto. Over the past twenty-five years, the unassuming 3,600-square-foot facility has become something of a mecca for the bouncy set. It’s where veterans Rosie MacLennan, Karen Cockburn, and Jason Burnett work with Team Canada coach Dave Ross, mere metres away from eleven-year-olds in Superman sweatshirts learning basic flips. It’s where the ba-bump, ba-bump of springs and taut fabric drowns out loudspeakers blaring Tiësto. And on a recent Friday evening, it’s where every Canadian in the room was rooting for the Portuguese.

Competitive trampoline is judged on the basis of difficulty, time of flight, and execution. For those at the top of their game, single pikes and tucks are relatively easy. Combining twists and backwards somersaults gets a bit more difficult. Soaring into the air and landing in the same spot over and over on a fourteen-by-seven-foot “bed,” even more so. In the space of eighteen to twenty seconds, an athlete must complete the equivalent of ten dives from a ten-metre platform that doesn’t actually exist (though the Spanish trampolín means exactly that: diving board).

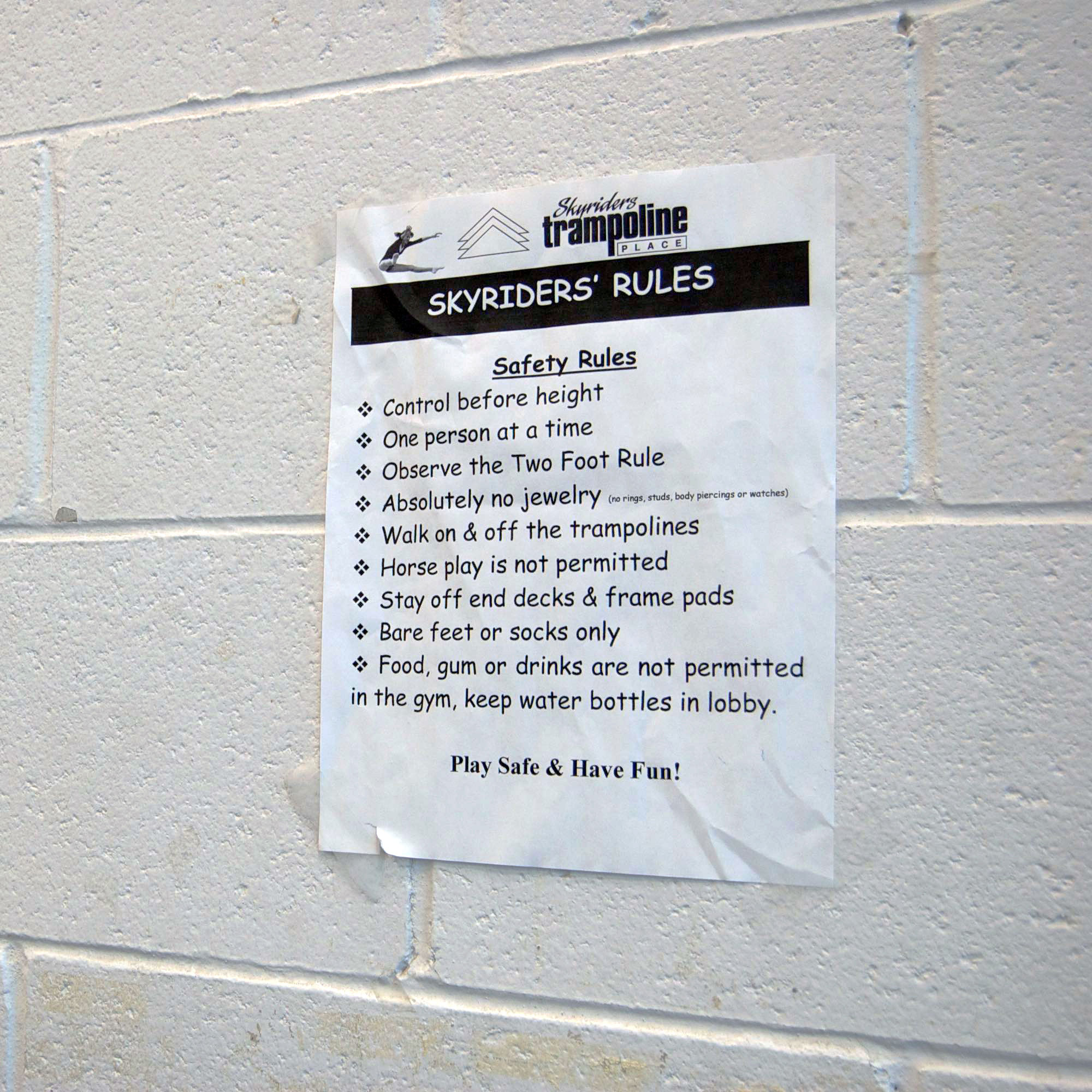

Everyone who trains at Skyriders and completes a routine—whether a bona fide trampoliner or a freestyle skier mastering tricks in the off-season—gets to Velcro his or her name and degree of difficulty to a white cinder-block wall crowded with personal records.

On this particular Friday, three of Portugal’s best trampoliners were winding up a week of training at Skyriders. It was their ninth practice, and their last chance to get as high on the wall as they could. Diogo Ganchinho accomplished a nineteen the day before—a spectacular mark—but the twenty-seven-year-old Olympian wanted better. Midway through his fifth or sixth attempt, he wavered and crashed onto the mats below (at Skyriders, the five beds are “in-ground,” meaning they sit at floor level). “Tired. So tired,” he said with a smile. “I’ll have to come back.”

Executing a routine is similar to running the 200-metre dash, in that it’s just long enough to force the body to draw on multiple energy systems. Lactic acid builds up, and each subsequent attempt gets more difficult. Ganchinho had at most two or three tries left in his legs.

With Rosie MacLennan, twenty-six, standing next to him, Ganchinho reviewed video of his failed attempt and laughed at his laboured form. As MacLennan waited to start her own routine—one that she’ll perform at the games in July—Canada’s sole gold medallist at the London Olympics said, to nobody in particular, “What an exciting practice.”

To the outsider, who might expect world-class gymnastics to be synonymous with Soviet-style intensity, the night had a dissonant quality. Some of the world’s best acrobats were bouncing around with kids literally underfoot. Lonely barbells, kicked-off sneakers, and dozens of phones lay scattered about. Nobody seemed in charge.

“People are shocked by the anarchy of our system,” said Ross, who opened Skyriders in 1990 and has coached Team Canada at four Olympics. “As I get older”—he’s sixty-five—“I try to be more of a mentor and less of a drill sergeant.”

Ross fell into the sport while studying physics at Queen’s University, in Kingston, Ontario; he has used his scientific training to help pioneer modern trampoline equipment ever since. But he couldn’t help Ganchinho better that nineteen—second-highest in Skyriders history, behind only Jason Burnett’s 20.6 (Burnett also holds the official world record, 18.8).

Ross headed to a corner crowded with crash pads and an old rowing machine, and pulled out an aluminum ladder. Ganchinho cooled down on an oversized bed, doing tricks to the amusement of his hosts; then he signed his name on a white placard, climbed the ladder’s rungs, and took a selfie near the top of the trampoline world.

As parents arrived to pick up their kids, Canadians and Portuguese alike pulled on their sweats and gathered for a group picture—no doubt a blurry one, as the photographer bounced up and down ever so slightly, taking shots with an iPhone she’d retrieved from the floor.

This appeared in the July/August 2015 issue.