The Chinese Communist Party is weighing in on Canada’s federal election—unofficially. On April 7, the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) task force revealed an orchestrated campaign of posts on the Chinese social media platform WeChat and through WeChat’s popular news account Youli-Youmian—linked by intelligence to the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission. The tone of the messages varied, but the efforts seemed to be directed at Chinese Canadians in order to shape their opinion of Liberal leader Mark Carney.

The SITE announcement marks the first time during a federal election that the public has been briefed on real-time efforts of foreign interference: when countries or their proxies try to influence people or institutions beyond their own borders. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service announced at the onset of the spring campaign that India and China will most likely try to influence the April election, and that Pakistan and Russia may also potentially try to subvert voting. Meanwhile, the Communications Security Establishment—Canada’s cryptologic agency which deals with cybersecurity prevention—has said that China, Iran, and Russia will likely use AI to try to meddle with individual candidates and party campaigns.

These warnings suggest that foreign interference in elections has not only become inevitable, but it’s evolving fast. And speaking frankly about the threat is critical to adapting to it.

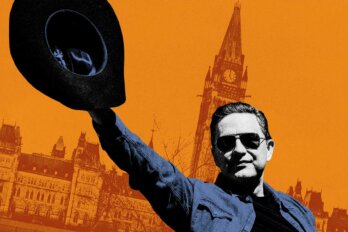

In January, the final report of the public inquiry into foreign interference in Canada’s electoral processes, led by Justice Marie-Josée Hogue, found that while foreign interference is a longstanding issue in Canada, the means and scope of the problem have expanded. In February, SITE reported that China was believed to have targeted the 2025 Liberal leadership campaign of Chrystia Freeland via negative messaging on a WeChat Youli-Youmian account. And in late March, the Globe and Mail reported that agents acting on behalf of India had allegedly been involved in the 2022 Conservative leadership contest, helping raise money and organizing support for Pierre Poilievre within the South Asian Canadian community. Poilievre won the leadership with 68 percent of the vote on the first ballot, and there was no evidence that he or his team were aware of this possible meddling.

Notably, Poilievre continues to refuse the security clearance necessary to receive classified briefings on foreign interference, stating that it would limit his ability to speak publicly. The position seems increasingly out of touch with the severity of the current geopolitical environment.

The Liberals, now leading in the polls, are also fielding accusations. In early April, the party’s new candidate for Markham-Unionville, an Ontario riding, faced allegations of foreign interference. Peter Yuen stepped into the race following incumbent Paul Chiang’s withdrawal, after Chiang made comments suggesting a Conservative candidate critical of China’s actions in Hong Kong should be handed over to the Chinese consulate in exchange for a bounty.

Critics allege Yuen is equally pro-China. Among his various connections to Beijing, Yuen, a former deputy chief with the Toronto Police Service, was listed as the honorary director of the Jiangsu Commerce Council of Canada, an organization with known ties to China’s United Front Work Department. The UFWD oversees influence, propaganda, and intelligence operations inside and outside of China’s national borders. JCCC executives also say Carney met with them during the Liberal leadership race, but he has denied doing so.

And earlier this week, SITE announced that China and authorities in Hong Kong were targeting Joe Tay, the Conservative candidate in Don Valley North, with negative messaging on social media platforms including WeChat, RedNote, TikTok, and Douyin. Tay is vocally opposed to Beijing’s crackdown on civil rights in Hong Kong, where there is a bounty for his arrest.

In a race that has upended long-held expectations, it’s not clear how allegations of foreign interference could sway voters’ decisions. But so far, the country has thwarted efforts to shape election results. China attempted to influence outcomes in various candidate races in both the 2019 and 2021 elections. India also tried to promote sympathetic candidates in a small number of ridings in 2021. In each of these cases, the Hogue inquiry found that Canadian institutions were uncompromised and that no parliamentarians were elected as a result of the tactics.

In 2024, the federal government approved Bill C-70 to counter foreign interference, which introduced wide-ranging legislation, including the creation of a foreign agent registry—examples of which already exist in Australia and the United States. While Canada may be better prepared to monitor the influence of rogue states during this election, thanks to the approval of Bill C-70, critics say it could lead to increased scrutiny of minority communities. Diaspora individuals may be more hesitant to engage with their communities and speak out publicly on issues linked to country-of-origin policies. The bill also fails to meaningfully address technological advancements, such as AI, that could aggravate security concerns.

This vulnerability needs to be addressed, given that foreign interference tactics can include cyberattacks, blackmail, social media attacks, illegal financing, disinformation, and AI deepfake video and audio content. Voice cloning or deepfake images are sometimes used to blackmail individuals in personal contexts and could be used to do so for political motivations, such as to create doctored clips of a candidate saying or doing something incriminating. But Canada currently lacks legislation specifically governing AI deepfakes.

In mid-April, The Logic reported on a cluster of fraudulent Facebook accounts spreading deepfake videos and posts, including one made to look like a CBC broadcast announcing a Carney-led passive income scheme; links in the fake article lead to scam pages. Meta currently blocks access to news sites on its platforms for Canadian users, but a Media Ecosystem Observatory survey published last August found that roughly 55 percent of Canadians use Facebook as a news source.

AI- and tech-fuelled interference campaigns often go beyond trying to influence who you should vote for and seek to erode trust in government and democratic institutions. This trend has become particularly pernicious as more and more Canadians shift away from consuming their news from legacy media. There is often no consensus about facts. The bifurcation of online news platforms and social media has resulted in people often seeing radically different news content, a fact foreign actors can easily exploit. Last September, a US indictment alleged that a right-wing media company based in Tennessee, and run by a Quebec-born social media influencer and her husband, was indirectly paid nearly $10 million (US) to create content favourable to Moscow. The payment came from RT, a Russian state-controlled media outlet that’s under sanctions.

Alarmingly, the US has become a major source of disinformation and foreign interference online. President Donald Trump, who has stated his preference for a Carney victory, regularly posts false, inflammatory statements on social media. Elon Musk’s X has been criticized for amplifying misinformation. And in January, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta would be ending third-party fact-checking in the US for Facebook, Instagram, and Threads.

American right-wing social media influencers have been increasingly focused on Canada. And some Canadian politicians are deliberately courting their platforms. Alex Jones, the far-right podcaster and known conspiracy theorist, recently interviewed and endorsed Maxime Bernier, leader of the far-right populist People’s Party of Canada.

Such actions by tech giants and right-wing personalities are especially worrisome given that polarised media landscapes are directly connected to wider political divides. Foreign interference and disinformation thrive when there is little consensus about facts and little faith in the outcome of fair elections, regardless of who is elected.

“By fostering distrust, creating division and preventing compromise, disinformation threatens this fundamental feature of democracy,” writes Justice Hogue in her final report. “Trust in Canada’s democratic institutions has been shaken, and it is imperative to restore it. This can only be achieved through greater transparency.”

Canadians aren’t alone in their predicament. Other elections in recent months, notably in Romania, Moldova, and Germany, have been targeted by foreign interference. But while we may not have control over foreign governments’ cyber troll armies, influencers, or AI content spamming our social media feeds, we can carefully scrutinize our individual media choices and how they might be shaping our voting decisions. Our ability to recognize, understand, and communicate openly about these threats could go a long way in ensuring that foreign interference may nip at our heels, but it will not bring our democracy down.