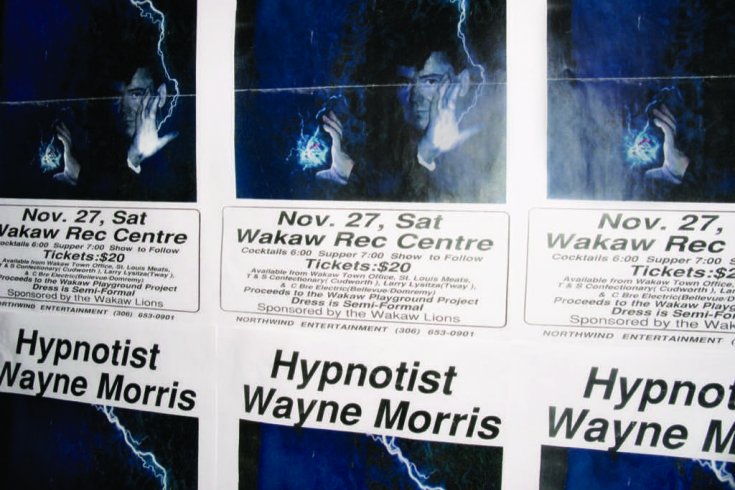

WAKAW—It has been a dull, dark winter in the small palindrome-town of Wakaw where I’ve recently put down roots. My partner Grant and I were just starting to adapt to life in rural Saskatchewan when the transmission blew on our car. After going mildly stir-crazy waiting for a replacement from BC, we decided it was time for a local night out. The big news in town was posted in the window of Wakaw Fine Foods. Wayne Morris, hypnotist, was coming to the Wakaw rec centre (dress: semi-formal, tickets: $20).

At eight o’clock on a Saturday night, we walk over to the community centre. The hall is packed. People huddle together amiably, their elbows perched on long, paper-covered tables peppered with rye-and-Cokes and domestic beer. The men are all sturdy, and they look relaxed sitting next to their gussied-up wives. The people of Wakaw are mostly of Ukrainian or German stock, the descendants of turn-of-the-century sod-busters.

Wayne Morris has arrived in a town where the farm economy is in a disastrous state and morale is low. Unless you can afford to farm an entire township here, you can’t reap enough money from the land to maintain a middle-class living. The only person here with certain money in his pocket is Morris. He hasn’t pulled up in a creaky wagon, potions swaying over dirt roads, but he doesn’t seem far removed from the miracle-tonic salesmen of old, either.

Morris, himself a rural Albertan, doesn’t risk rejection in prairie towns on Saturday nights to get rich, though. He makes his living going from small town to small town across Canada, feeding what he calls his “need for attention.” “Every entertainer is a sick person,” he chuckles wistfully to me later. Before the show begins, I see him standing in profile, focused, waiting to make his entrance. He’s dressed formally and sporting a cheap headset microphone. He has the strained, smiling mask of the sad clown.

When he climbs onstage and puts out a call for volunteers, the locals rush up in what seems like the desperation of housebound farmers mired in the early stages of an nhl-free prairie winter. But it quickly becomes clear that not everyone is looking to be entertained: five male volunteers and one female seated stage right are stubbornly unco-operative. They kibbitz with one another, exchanging knowing glances as Morris feels out the other volunteers.

The skeptical group is made up mainly of older, strong-willed farmers. They practically dare Morris to hypnotize them, their looks of bored intimidation no doubt honed on weary spouses and grasping bankers. One suspender-clad man is clearly the group’s alpha male—his moustache is the bushiest, his arms the most firmly crossed. Morris works his “magic” on this taciturn man for ten minutes. The show lags. The mesmerist stands over his volunteer, imploring him as part of the hypnosis pre-test to close the gap between his upheld fingers. His fingers remain the same. He has his own agenda: embarrass the hypnotist. “You aren’t listening to me,” Morris complains. “You have to be willing in order for this to work.” The other five aren’t closing their fingers either. They come close a few times, but their joshing camaraderie with the man in suspenders has earned him their allegiance.

Finally, Morris gives up and summarily dismisses them and they go back to their seats looking surprised, but unaffected. If they haven’t surrendered their family homesteads after a hundred years, Morris’s antics won’t sway them. On the phone with me later, Morris says he has nightmares about incidents like these for days afterwards.

With the volunteers now culled to ten willing subjects, Morris performs with the flair of Steve Martin’s Jonas Nightengale character in Leap of Faith. “Sexpot” believes she’s an exotic dancer writhing around to Hot Chocolate’s “You Sexy Thing.” A dignified older man imagines that he has hemorrhoids. A young Spiderman scales the walls. Morris brings them all back to “reality” and dismisses them to circulate, still entranced. The crowd is into it; the show has become what Morris hoped it would be.

He recalls his subjects to the stage and suggests to them that there is an emergency. They “urgently” usher everyone out of the building. Some file out. The skeptics remain seated or join the lineup for drinks, content in the company of friends. Grant and I reach for our coats. We’ve seen enough. When the show ends, Morris will pack up and seek applause in some other small town. Not us; we’re at home with the skeptics in Wakaw, car-less, and waiting it out for spring.