Everyone in Canada with any power has the same job. It doesn’t matter if you’re prime minister, minister of foreign affairs, or premier of Alberta; it doesn’t matter if you’re the mayor of a small town or a CEO of a major company, if you run a cultural institution or a mine. Canadians with any power at all have to predict what’s going to happen in the United States. The American economy remains the world’s largest; its military spending dwarfs every other country’s; its popular culture, for the moment, dominates. Canada sits in America’s shadow. Figuring out what will happen there means figuring out what we will eventually face here. Today, that job means answering a simple question: What do we do if the US falls apart?

American chaos is already oozing over the border: the trickle of refugees crossing after Trump’s election has swollen to a flood; a trade war is underway, with a US trade representative describing Canada as “a national security threat”; and the commander-in-chief of the most powerful military the world has ever known openly praises authoritarians as he attempts to dismantle the international postwar order. The US has withdrawn from the UN Human Rights Council, pulled out of the Paris climate agreement, abandoned the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, and scorned the bedrock NATO doctrine of mutual defence. Meanwhile, the imperium itself continues to unravel: the administration is launching a “denaturalization task force” to potentially strip scores of immigrants of their US citizenship, and voter purges—the often-faulty processes of deleting ineligible names from registration lists—are on the rise, especially in states with a history of racial discrimination. News of one disaster after another keeps up its relentless pace but nonetheless shocks everybody. If you had told anyone even a year ago that border guards would be holding children in detention centres, no one would have believed you.

We have been naive. Despite our obsessive familiarity with the States, or perhaps because of it, we have put far too much faith in Americans. So ingrained has our reliance on America been, we are barely conscious of our own vulnerability. About 20 percent of Canada’s GDP comes from exports to the United States—it’s a trade relationship that generates 1.9 million Canadian jobs. This dependence is even clearer when it comes to oil—something the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which will ship our natural resources to global markets, could remedy. The fact that the premier of British Columbia tried to stall the project in a show of regional power is a sign of a collective failure to recognize how perilous our position is. Ninety-nine percent of our oil exports go to a single customer. And that customer is in a state of radical instability. According to a recent poll from Rasmussen Reports, 31 percent of likely US voters anticipate a second civil war in the next five years.

We misunderstood who the Americans were. To be fair, so did everybody. They themselves misunderstood who they were. Barack Obama’s presidency was based on what we will, out of politeness, call an illusion, an illusion of national unity articulated most passionately during Obama’s keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention: “There is not a liberal America and a conservative America—there is the United States of America. There is not a black America and a white America and Latino America and Asian America—there’s the United States of America.” It was a beautiful vision. It was an error. There is very much a red America and a blue America. They occupy different societies with different values, and the political parties are emissaries of those differences—differences that are increasingly irreconcilable.

Many Canadians operate as if this chaos were temporary, mainly because the collapse of the United States and the subsequent reorientation of our place in the world are ideas too painful to contemplate. But, by now, the signs have become impossible to ignore. The job of prediction, as impossible as it may be, is at hand.

★★★

after the midterms, special counsel Robert Mueller presents his report to the deputy attorney general, and America is thrown into immediate crisis.

Congressional committees call a parade of witnesses who describe the president’s collusion and obstruction of justice in detail. The Republicans respond on television and through public rallies. Rudolph Giuliani, on Fox & Friends, declares that “flipped witnesses are generally not truth-telling witnesses.” Trump airily waves away the Mueller report at a rally for 100,000 supporters in Ohio: “I’m going to pardon everyone anyway, so it’s all a waste of taxpayer dollars.” A ProPublica survey shows Americans are divided on impeachment.

Since the Republican base remains overwhelmingly supportive of the president, the House Republicans, arguing the need for “national unity,” do not vote for impeachment, which requires a majority in the House. The vote then goes to the Senate, where Republicans refuse to remove Trump from office. Mueller presses instead for an indictment. There is no legal precedent for indicting a sitting president.

The case proceeds to a federal judge overseeing a grand jury and then eventually to the Supreme Court, which has been tipped rightward with Trump nominees. The court rules that the president cannot be indicted. Protests fill the streets of Washington, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Polls vary. Somewhere around 40 percent of Americans believe the government is legitimate. Somewhere around 60 percent do not.

Steven Webster is a leading US scholar of “affective polarization,” the underlying trend that explains the partisan hatred tearing his country apart. In 2016, he and his colleague Alan Abramowitz published the paper “The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century,” which was one of the first attempts to track the steady growth of the mutual dislike between Republicans and Democrats.

Affective polarization is a crisis that transcends Trump. If Hillary Clinton had won the 2016 election, the underlying threat to American stability would be as real as it is today. Each side—divided by negative advertising, social media, and a primary system that encourages enthusiasm over reason—pursues ideological purity at any cost because ideological purity is increasingly the route to power. Abramowitz runs a forecasting model that has correctly predicted every presidential election since 1992. After he modified his model in 2012 to take into account the impact of growing partisan polarization, it projected a Trump victory in 2016—and Abramowitz rejected the results. That should be a testament to the power of the model; it traced phenomena even its creator didn’t want to believe. Nobody wants to see what’s coming.

Webster describes a terrible spiralling effect in action in the US. Anger and distrust make it very difficult to go about the business of governing, which leads to ineffective government, which reinforces the anger and distrust. “Partisans in the electorate don’t like each other,” he says. “That encourages political elites to bicker with one another. People in the electorate observe that. And that encourages them to bicker with one another.” The past few decades have led to “ideological sorting,” which means that the overlap between conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans has more or less disappeared, eliminating the political centre.

But it’s the people in the parties, not just the ideas in the parties, that have changed. “There’s a really big racial divide between the two parties,” says Webster. The nonwhite share of the American electorate has been increasing tremendously over the last few decades, and most of those voters have chosen to affiliate with the Democratic Party. What worries Webster isn’t that the Republican Party remains vastly whiter than the Democratic Party, which, in turn, has become more multicultural—though that’s happened. The real source of the crisis is that white Republicans have become more intolerant about the country’s growing diversity. According to the PRRI/The Atlantic 2018 Voter Engagement Survey, half of Republicans agree that increased racial diversity would bring a “mostly negative” impact to American society. During the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush years, there really wasn’t as much of a difference between the racial attitudes of white people in both parties. That’s no longer true. “During the Obama era, if you look at just white Republicans, 64 percent scored high on the racial-resentment scale. For white Democrats, it was around 35 percent,” says Webster, who analyzed data from the American National Election Studies. The Republican Party has become the party of racial resentment. If it seems easier for Americans to see the other side as distinct from themselves, that’s because it is.

The loathing just keeps growing. In 2016, the Pew Research Center found that 45 percent of Republicans and 41 percent of Democrats declared the opposing party’s policies a threat to the nation’s well-being—up from 37 and 31 percent, respectively, in 2014. Political adversaries regard each other as un-American; they regard the other’s media, whether Fox News or the New York Times, as poison or fake news. A sizable chunk also don’t want their children to marry members of the opposing party. “A lot of people say, ‘What would happen if there were a very independent-minded candidate, a third-party candidate with no partisan label, who would come and unite America?’” Webster says. “That is absolutely not going to happen.” In surveys, independents seem to make up a large percentage, but if you press those self-identified independents on their voting behaviour, they look just like strong partisans. Abramowitz’s own analysis of the 2008 election suggests that only about 7 percent of American voters are truly independent in that they don’t lean toward one party or the other.

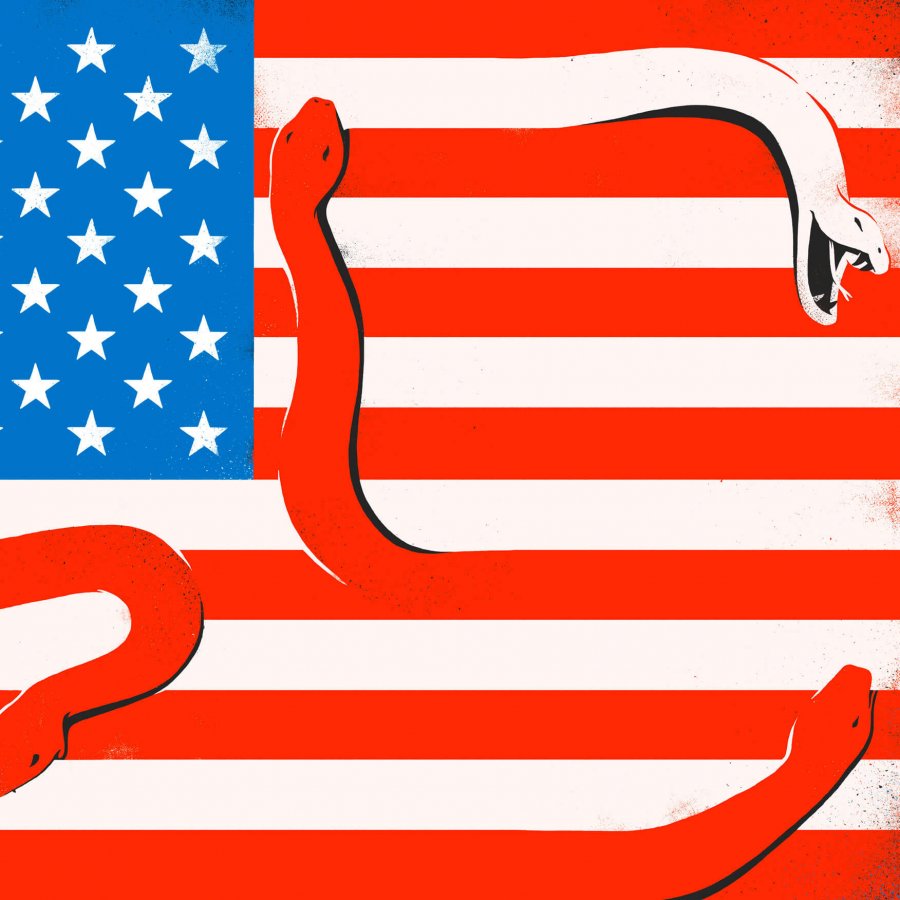

America is becoming two Americas, Americas which hate each other. If the Democrats represent a multicultural country grounded in the value of democratic norms, then the Republicans represent a white country grounded in the sanctity of property. The accelerating dislike partisans feel for the other side—the quite correct sense that they are not us—means that political rhetoric will fly to more and more dangerous extremes. In September 2016, Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin gave a speech at the Values Voter Summit in which he openly speculated about violence if Hillary Clinton were elected: “Whose blood will be shed?” he asked. “It may be that of those in this room. It might be that of our children and grandchildren.” More recently, Michael Scheuer, a former senior CIA official, wrote that it was “quite near time” for Trump supporters to kill Trump opponents (the blog post has since been deleted).

Such explicit calls for violence are being driven by a dynamic of othering that, once started, might not be easily stopped—except by disaster. “I don’t see an optimistic scenario here,” Webster acknowledges.

★★★

the man who assassinates the president uses a .50-calibre Barrett rifle with armour-piercing incendiary ammunition. He purchased it legally at a gun show.

The assassin’s note, posted on Facebook the moment after the assassination, amounts to a manifesto, but it’s nothing Americans haven’t heard before. He quotes Thomas Jefferson, about the tree of liberty refreshed by the blood of patriots. He compares the president to Hitler. “People say that if they had a time machine they would go back and remove the monsters of history,” he writes. “I realized that there is a time machine. It’s called the present and a gun.”

The assassination of the president leads, at first, to a great deal of public hand wringing. On social media, the assassin’s heroism is suggested and then outright celebrated. Within a month, the assassin’s face appears on T-shirts at rallies.

The assassination is used as a pretext for increasing executive power, just as in the aftermath of September 11. Americans broadly accept the massive curtailing of civil rights and a dramatic increase in the reach of the surveillance state as the price of security.

Scott Gates is an American who lives in Norway, where he studies conflict patterns at the Peace Research Institute Oslo. His work has been devoted to political struggles in the developing world, where most of the civil wars happen. He now sees that his research has applications at home. The question for the US, as it is for every other country nearing the precipice, is whether civil society is strong enough to hold back the ferocious violence of its politics. Gates isn’t entirely sure on that point anymore.

Democracies are built around institutions that are larger than partisan struggle; they survive on the strength of them. The delegitimization of national institutions “almost inevitably leads to chaos,” Gates says, citing Trump’s constant attacks on the FBI, the Department of Justice, and the judicial system as typical of societies headed toward political collapse, as happened in Venezuela under Hugo Chávez. The Supreme Court has already been the engine of its own invalidation. Since the ideologically divided Bush v. Gore ruling which decided the 2000 election, the Supreme Court no longer represents transcendent interests of national purpose. Trust in the Supreme Court, according to a recent Gallup poll, is split sharply along partisan lines, with 72 percent of Republicans reporting approval compared to 38 percent of Democrats. Mitch McConnell’s decision to make the appointment of a Supreme Court justice an election issue in 2018—an appointment that will likely not get the support of a single Democratic senator—is an example of a political institution being converted into a token in a zero-sum game, exactly the kind of decision that has played a part in destabilizing smaller, poorer countries. Once the norm has been shattered, it becomes difficult to glue back together.

In a sense, the crisis has already arrived. Only the inciting incident is missing. In December 1860, the fifteenth president of the United States, James Buchanan, believed he was offering a compromise between proslavery and antislavery groups in his State of the Union address, but his remarks preceded the Civil War by four months. His declaration—that secession was unlawful but that he couldn’t constitutionally do anything about it—became the moment when America split and the war was inevitable.

Few American institutions now seem capable of providing acceptably impartial arbitration—not the Supreme Court, not the Department of Justice, not the FBI. The only institution in American life still seen as being above politics is the military, which, according to a 2018 Gallup survey, is the most trusted institution in the country, with 74 percent of Americans expressing confidence in it. No surprise: the worship of the armed forces has been ingrained into ordinary American life since the Iraq War. Not so much as a baseball game can happen in the US without a celebration of a soldier. Members of the military are even given priority boarding on major US airlines.

If civil order were threatened, could America look to the troops to step in? In 2017, about 25 percent of Democrats and 30 percent of Republicans said they would consider it “justified” if the military intervened in a situation where the country faced rampant crime or corruption. In an article in Foreign Policy, Rosa Brooks, previously a counsellor to the US undersecretary of defence for policy and a senior adviser at the US State Department, could imagine “plausible scenarios” where military leaders would openly defy an order from Trump.

A coup would hardly be unprecedented, in global terms: in Chile, in the 1970s, a democracy in place for decades devolved into winner-take-all hyperpartisan politics until the military imposed tranquilidad. But even the armed forces might not be enough of a power to stabilize the United States. There is a huge gap between enlisted troops and officers when it comes to politics. According to a poll conducted by the Military Times, a news source for service members, almost 48 percent of enlisted troops approve of Trump, but only about 30 percent of officers do. It appears that the American military is as divided as the country.

Would a coup even work? The American military hasn’t been particularly good at pacifying other countries’ civil wars. Why would it be any good at pacifying its own?

There are trends—which no country can escape, or that few have escaped, anyway—that forecast the likelihood of civil conflict.

A 2014 study from Anirban Mitra and Debraj Ray, two economics professors based in the UK and US respectively, examined the motivations underlying Hindu-Muslim violence in India, where Hindus are the dominant majority and Muslims one of the disadvantaged minorities. The two professors found that “an increase in per capita Muslim expenditures generates a large and significant increase in future religious conflict. An increase in Hindu expenditures has a negative or no effect.”

That suggests revolution is not like the communist prophets of the nineteenth century believed it would be, with the underclass rising up against their oppressors. It’s sometimes the oppressors who revolt. In the case of India, according to Mitra and Ray’s research, riots start at the times and in the places when and where the Muslims are gaining the most relative to the Hindus. Violence protects status in a context of declining influence.

“A very similar pattern of resentment can be seen in the US right now,” Gates tells me. The white working-class community perceives its position in life as worsening. “At the same time,” he says, “the Latino community and the black community have been improving their status, relative to where they were.” In other words, white resentment doesn’t necessarily reflect actual changes in financial well-being as much as frustration in the face of minorities making significant gains. And, as status dwindles, the odds of violence increase. Gates points to the bloody Charlottesville rally as the kind of flashpoint fuelled in part by a sense of aggrieved white diminishment.

We can track the destabilizing effect of threatened status in other conflicts around the world. A struggle between ethnic groups losing and gaining privilege contributed, in varying degrees, to the brutality between Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda in the 1990s and to the earlier Biafran War in Nigeria.

There are deeper anxieties and more troubling visions for anyone whose job is to predict where America is headed. For the really scary stuff, you have to go to Robert McLeman, who studies migration patterns and climate change at Waterloo’s Wilfrid Laurier University. He’s got a kind of cheerful and upbeat way of describing the spread of total chaos that’s disarming.

Climate change can bring about political chaos, in large part through migration. “Military people call it a threat multiplier,” McLeman tells me. Usually, migration is the last resort, a response to changes that are unpredictable and unexpected. So Bangladesh, to take an example, will typically not experience mass migration because of flood, because people in that region have been dealing with floods for thousands of years. But a drought could cause a serious crisis, causing waves of migration into India.

As its departure from the Paris climate agreement clarified, America is barely able to face the fact that climate change exists, never mind able to come up with effective strategies to accommodate itself to the reality it is already facing. In 2012, a hot and dry year in the US, soy bean, sorghum, and corn yields were down as much as 16 percent. And, because the country is a major producer of commodity crops, the drought pushed up food prices at home and globally. There are a lot more 2012s coming. And, of course, America is utterly unprepared for the vastly less predictable catastrophes of climate-change extremes, as New Orleans and Puerto Rico have both learned to their destruction.

Most worrying to McLeman is the fact that American populations are growing in the areas that are most vulnerable to unpredictable catastrophes. They include coastal New York, coastal New Jersey, Florida, coastal Louisiana, the Carolinas, the Valley of the Sun, the Bay Area, and Los Angeles. Many Central Americans who were separated from their children at the American border were fleeing gangs and political instability, but they were also fleeing drought. “Environmentally related migration already happens—we’re just seeing the thin edge of the wedge right now,” McLeman says. Get used to refugees at the Canadian border. There may be more of them.

All right, you say, there are conditions that lead to civil war: hyperpartisanship, the reduction of politics to a zero-sum game, the devastation of law and national institutions in the context of environmentally caused mass migration, and the relative decline of a privileged group. Fine. But when you land at JFK and line up for Shake Shack, where are the insurgents? Then again, in other countries and in other times, it’s never been clear, at least at first, whether a civil war is really underway. Confusion is a natural state at the beginning of any collapse. Who is a rebel and who is a bandit? Who is a freedom fighter and who is a terrorist? The line between criminality and revolution blurred in Mexico, in Cuba, and in Ireland. The technical definition of a civil war is 1,000 battle deaths a year. Armed conflict starts at twenty-five battle deaths a year. What if America is already in an armed conflict and we just haven’t noticed? What if we just haven’t noticed because we’re not used to uprisings happening in places where there’s Bed Bath & Beyond?

If there is an insurgency-in-waiting, it will likely be drawn from the hundreds of antigovernment groups across the country, many of which were readying for civil war in 2016 in the event of a Hillary Clinton presidency. One of the most extreme examples is an ideological subculture made up of “sovereign citizens,” who believe that citizens are the sole authority of law. Ryan Lenz, a senior investigative reporter for the Southern Poverty Law Center, has been researching them for nearly eight years. It’s been a terrifying eight years. A 2011 SPLC report pegged the number of the sovereign citizens, a mix of hard-core believers and sympathizers, at 300,000. The movement, Lenz believes, has grown significantly since then.

To put that in perspective, the Weather Underground was estimated to contain hundreds of members. Some guesses put the number of Black Panthers as high as 10,000, a debatable figure. Both the Underground and the Panthers—who talked a great deal about the justification for violence but managed to commit relatively little—caused immense panic in the late sixties and seventies and massive responses from the FBI. Sovereign citizens, and antigovernment extremists as a whole, are part of a much larger movement, many are armed, they anticipate the government to fall in some capacity, and they are responsible for about a dozen killings a year. The FBI has addressed them, and their growing menace, as domestic terrorism. In 2014, a survey conducted with US officers in intelligence services across the country found sovereign citizens to be the country’s top concern, even ahead of Islamic extremists, for law enforcement.

Theirs is a totalizing vision of absolute individual freedom and resistance to a state they believed is ruled by an unjust government. Rooted historically in racism and antisemitism—they hovered on the extreme fringes of American politics until the 2008 housing crisis and the election of Barack Obama—sovereign citizens believe they are sovereign unto themselves and, therefore, can ignore any local, state, or federal laws and are not beholden to any law enforcement. According to the SPLC, the sovereign citizens believe that the federal government is an entity that operates outside the purview of the US Constitution for the purposes of holding citizens in slavery.

“Understanding sovereign-citizenry ideology is like trying to map a crack that develops on your windshield after a pebble hits it. It’s a wild and chaotic mess,” Lenz tells me. Ultimately, the movement boils down to a series of conspiracy theories justifying nonobedience to government agents. Sometimes it expresses itself as convoluted tax dodges, as in the case of the self-proclaimed president of the Republic for the united States of America (RuSA), James Timothy Turner, who was convicted of sending a $300 million fictitious bond in his own name and aiding and abetting others in sending fictitious bonds to the Treasury Department. Turner was sentenced to eighteen years in prison. Bruce A. Doucette, a self-appointed sovereign “judge,” received thirty-eight years in jail for influencing, extorting, and threatening public officials.

At other times, the spirit of disobedience expresses itself in straight violence, as in the case of Jerry and Joseph Kane, a father-son pair who, in 2010, killed two police officers at a routine traffic stop in West Memphis, Arkansas. Or in the case of Jerad and Amanda Miller who, in 2014, after killing two police officers at a CiCi’s Pizza in Las Vegas, shouted to horrified onlookers that the revolution had begun.

★★★

the summers grow hotter, and the yields on corn and beans grow smaller. During the first drought, the declines are small. The year after is more serious. Food prices spike. Inflation rises, leading to a sharp jump in unemployment.

China, holding $1.18 trillion (US) of US government debt, dumps its bonds as a retaliatory measure against US tariffs. This causes every other country to panic and sell their holdings as well, bringing China closer to becoming the global reserve currency. With the US bond market routed, higher interest rates ripple through the economy, slowing it down.

The hardest hit are the farming communities dependent on commodity crops. The antigovernment movements in these areas swell and organize. They elect local politicians, particularly sheriffs. Pockets of the southern and midwestern states, under these sheriffs, believe that the federal government has no legitimate authority over them.

By this time, a Democratic president has come to power, with significantly more socialistic ideas than any president in history. She eventually passes legislation imposing national education and health care programs. The local authorities take these programs as illegitimate government interference and, in the heated rhetorical climate, claim the mantle of resistance, which is also taken up by armed insurgencies

The National Guard swiftly imposes order. But the states consider themselves, and are considered by others, to be under occupation.

The borders of North America are, in their ways, as patchwork as those in the Middle East and as nonsensical. The French lost to the English. The British lost to the Americans. The Mexicans lost to the Americans. The South lost to the North. The alignments of any political unity are forced; they defy historical experience, geography, ethnicity, or political ideology. And that’s why it’s all so breakable, so fragile.

The antigovernment extremists know who they are. They see themselves as the true Americans. And who could deny there’s a certain justice in the claim? What could be more American than tax rebellion, the worship of violence as political salvation, a mangled misinterpretation of the Constitution, and a belief system derived sui generis that blurs passionate belief with straight hucksterism? The next American civil war will not look like the first American Civil War. It will not be between territories over resources and the right to self-determination. It will be a competition over distinct ideas of what America is. It will be a war fought over what America means. Is it a republic with checks and balances or a place that yields to the whims of a president’s executive power? Is the United States a country of white settlers or a nation of immigrants? It’s also possible, maybe probable, that the country will never get answers.

★★★

in canada, in the middle of the American collapse, the Queen dies. Charles III accedes to the throne. Despite the prospect of having his face on the money, there is no serious attempt to challenge the status quo. It’s a hard time to argue in favour of any dramatic political reordering. For the same reason, though Quebec separatism rises and falls as usual, a new referendum on independence is put away for a generation; there’s enough instability in North America.

The refugee crisis at the border continues to grow, quickly outstripping the ability of border agencies to manage it effectively. Canada’s appetite for refugees withers as the tide swells. Calls for order grow louder. Asylum centres appear as in Germany and Denmark.

Despite restrictions on refugees from the United States, Canada remains scrupulously multicultural. When a visa applicant from India, hoping to work at Google, is separated from his daughter at the US border, and they are reconciled after a month, the world’s technological elite move to Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal. People who have young families and aren’t white find the prospect of building a career in the United States too precarious.

The hunger among young Canadian talent for New York and Los Angeles and San Francisco naturally diminishes for the same reason. Innovators cannot just head south when they encounter the inertia which defines so much of Canadian life. The stolid cultural industries and the tech world lose their garrison mentality, at least somewhat.

To sum up: the US Congress is too paralyzed by anger to carry out even the most basic tasks of government. America’s legal system grows less legitimate by the day. Trust in government is in free fall. The president discredits the FBI, the Department of Justice, and the judicial system on a regular basis. Border guards place children in detention centres at the border. Antigovernment groups, some of which are armed militias, stand ready and prepared for a government collapse. All of this has already happened.

Breakdown of the American order has defined Canada at every stage of its history, contributing far more to the formation of Canada’s national identity than any internal logic or sense of shared purpose. In his book The Civil War Years, the historian Robin Winks describes a series of Canadian reactions to the early stages of the first American Civil War. In 1861, when the Union formed what was then one of the world’s largest standing armies, William Henry Seward, the secretary of state, presented Lincoln with a memorandum suggesting that the Union “send agents into Canada…to rouse a vigorous continental spirit of independence.” Canadian support for the North withered, and panicked fantasies of imminent conquest flourished. After the First Battle of Bull Run, a humiliating defeat for the Union, two of John A. Macdonald’s followers toasted the victory in the Canadian Legislative Assembly. The possibility of an American invasion spooked the French Canadian press, with one journal declaring there was nothing “so much in horror as the thought of being conquered by the Yankees.”

The first American Civil War led directly to Canadian Confederation. Whatever our differences, we’re quite sure we don’t want to be them.

How much longer before we realize that we need to disentangle Canadian life as much as possible from that of the United States? How much longer before our foreign policy, our economic policy, and our cultural policy accept that any reliance on American institutions is foolish? Insofar as such a separation is even possible, it will be painful. Already, certain national points of definition are emerging in the wake of Trump. We are, despite all our evident hypocrisies, generally in favour of multiculturalism, a rules-based international order, and freedom of trade. They are not just values; the collapsing of the United States reveals them to be integral to our survival as a country.

Northrop Frye once wrote that Canadians are Americans who reject the revolution. When the next revolution comes, we will need to be ready to reject it with everything we have and everything we are.