My first memory of America is driving through the Black Hills of South Dakota on a hot August day in a black Chevrolet Corvair without air conditioning. It was 1963 and the Corvair still had two carefree years before Ralph Nader would declare it the unsafest car on the road. We were three months away from Zapruder and jfk’s ghastly caravan. It was a safe time, perhaps the safest. My parents and brother and I stayed in motels with swimming pools and splashed in the 90°F heat and ate at Rib Shacks or bbq Barns. During those blanched days, we drove to roadside attractions: a Flintstones theme park where you could play miniature golf using a plastic club in the shape of a pterodactyl. At another stop, a man milked a rattlesnake, holding its fangs over a glass as the venom leaked out. He then wrestled an alligator in a dusty ring, flipping it onto its back, which produced a reptilian cartoon smile.

We stood in front of Mount Rushmore, the “shrine of democracy,” and drank Hires root beer and wondered at the monumentality of those faces, which had taken sculptor Gutzon Borglum fourteen years to carve. The four presidents represented all Americans, we were told by a guide. George Washington presided over the nation’s birth, Jefferson honed its ideals, Lincoln preserved the Union, and Teddy Roosevelt moved the country from rural republic to world power.

The back seat of our Corvair folded down (making it even less safe), and as we drove back to the border through the night I lay on a blanket, staring at the fearless republic retreating through the rear window, moments of neon eclipsed by blackness.

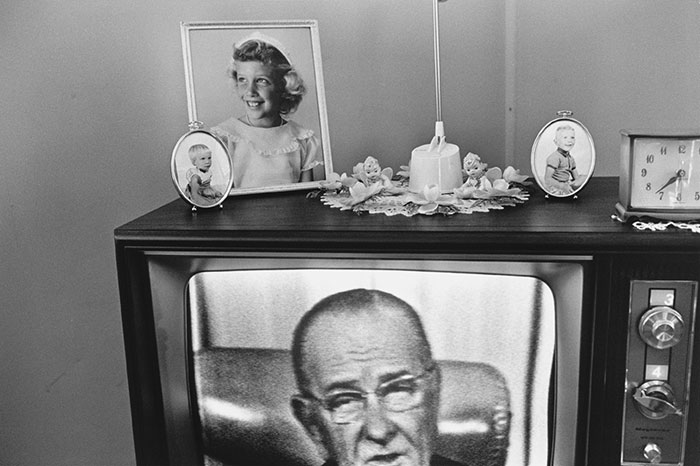

On January 16, 1965, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson was at the ranch of American President Lyndon B. Johnson. The rangy, crude Texan introduced the Canadian leader to the media as “my good friend Drew Pearson.” The physical contrast was acute. Pearson lisped politely and wore bow ties and looked like a class valedictorian, while Johnson carried a sense of physical menace in that long body. Pearson was photographed wearing hunting gear, an image that looked like an unfortunate play date arranged by a negligent mother.

In February, lbj ordered the bombing of North Vietnam. Two months later, Pearson was at Temple University in Philadelphia, and in his speech he suggested that a temporary cessation of the bombing might bring the North Vietnamese back to the bargaining table. When the two met at Camp David, the presidential retreat, lbj took Pearson by the lapels and shoved him against the rustic cabin. “Lester, you pissed on my rug!” he yelled. So much for diplomacy.

Pearson has emerged the greater man: winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, the inventor of the peacekeeping force, ahead of his time. He was a genuine statesman, before we understood them to be an endangered species. He helped define Canada’s role internationally, a desperate priority at the time, and one that still nags. And yet, as an eleven-year-old I yearned for lbj’s Daniel Boone persona. He exuded power and confidence. Pearson looked like one of those fathers who threw a baseball like a girl, an embarrassment.

It was difficult not to envy the United States—that breezy confidence and oppressive sexuality, its skirt billowing, breasts barely contained. Comedian Bill Maher, commenting on the world’s perception of America during Kennedy’s time, noted that the country had been loved and envied. “Now we’re the asshole,” he said. How did it become the asshole? This past summer, in a Pew Research Center poll of sixteen countries, only three had a more favourable view of the United States than they did of China—India, Poland, and the United States itself. George Bush has enlisted Karen Hughes, one of his chief image-makers and the undersecretary of state for public diplomacy, to “rebrand” the United States in the Arab world. The language implies that America is a product, a fair-enough assessment, and Hughes’ approach has been to teach Arab children that America is a force for good, to fight “propaganda with truth,” almost always a losing battle.

An image consultant might have been a good hire here too, after the United States ignored a nafta ruling in Canada’s favour on softwood lumber exports. Even the Canadian architects of the Free Trade Agreement, among them Pat Carney, Derek Burney, and Gordon Ritchie, denounced the Americans as “jackboot negotiators” and a “schoolyard bully” and stated that it was time to take a stand. The flagrant rejection of the rule of law elicited editorial and political outrage and revived familiar critiques of American exceptionalism, the country’s skittish relationship with international initiatives (the salt talks, Kyoto, the United Nations, the World Court). Is Noam Chomsky right; has America become a rogue state?

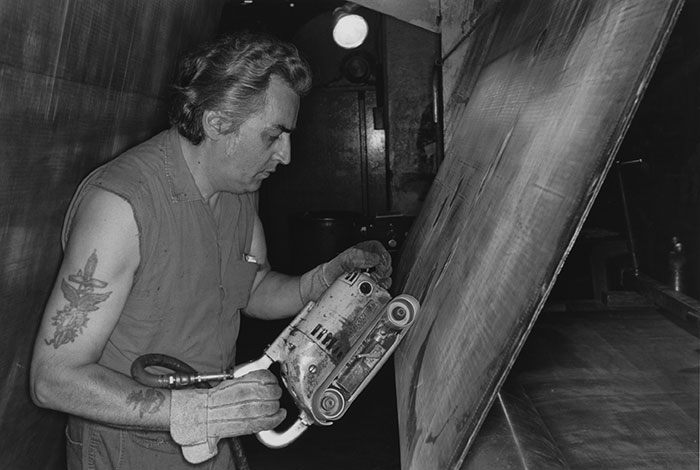

Foreign unease is matched by domestic grief and uncertainty. The despairing crescendo of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina produced both an outpouring of sympathy from the international community and muted censure. With US Army regulars and reservists in Iraq, the federal response was compromised, and on cnn came the daily cry that America could no longer protect its own. The anarchy witnessed in those first few days produced real fear both at home and abroad, a visceral glimpse of the world’s superpower as vulnerable and confused. Instead of the can-do spirit of American enterprise, everyone pulling together, there was the voodoo apparition of environmental neglect, tortured racial history, social inequities, and the rule of the gun all rising from the grave and wading through the muddy waters of Louisiana.

“The Lord Jesus is going to come on time. If we just wait,” said Condoleezza Rice from nearby Alabama. Neither Jesus nor President Bush arrived on time as it turned out, and the devil rejoiced. That the government appealed to a higher power, that it publicly pined for a pre-lapsarian innocence that would erase every sin, was unsettling. Equally unsettling was Bush’s announcement soon after that not just evolution but creationism should appear in school curricula. “Both sides ought to be properly taught,” he said. This was presented under the banner of freedom, the idea that debate is enriching. And it was, at the Scopes trial eighty years ago. It is less so now.

The current state of the nation recalls Sarah Winchester, heiress to the considerable Winchester firearms fortune. The “rifle that won the West” left her with $20 million ( US), but she believed that she was cursed by all the people who had been killed by it. She thought the only way to keep those spirits at bay was to build additions to her house. In 1884 she hired crews to work around the clock, seven days a week, for the next thirty-eight years. When Sarah died in 1922, the house had 160 rooms and forty staircases, many of which didn’t go anywhere, designed to throw her ghosts off the trail. It is an apt metaphor, ceaseless expansion as a way to avoid looking at domestic sins. In his 1964 novel, Herzog, Saul Bellow wrote of the America “[w]hich spent military billions against foreign enemies but would not pay for order at home. Which permitted savagery and barbarism in its own great cities.” Diverting attention and resources toward foreign goals has allowed the country to mask essential truths and internal contradictions, to live in a state that resembles adolescence.

The day after Katrina struck, Bush turned his rhetorical attention back to the war on terrorism. He has fuelled the concept of Manifest Destiny with biblical rhetoric and with patriotism, and at times they are indistinguishable. Patriotism may be attached to noble principles, but in practice it is often visceral and simplistic; that’s why it is so dangerous. In defining patriotism, Adlai Stevenson noted that it was often easier to fight for principles than to live up to them.

Going across the border now, there isn’t the envy I felt as a child. Buffalo, where Torontonians went to swing thirty years ago, is half the size it was then, a beleaguered city that looks like a border outpost being abandoned by a retreating army. Detroit remains blighted, its golden suburbs the result of endless flight. Even some of those perfect Rockwell towns have suffered. In Quebec I went from the lush, well-tended town of Sutton, to Richford, Vermont, an impoverished place that still has its great white houses, but the paint is peeled, and the flags are faded in the yards. The patriotism that I admired as a child seems a tainted commodity now.

Most of my first year was spent on the mit campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while my father was finishing graduate school. My pregnant mother had given birth to me in Fort Frances, Ontario, my father’s hometown, where she had the assistance of my grandmothers and I had the sanctity of Canadian citizenship. I lived in Fort Frances, nominally my hometown, for four months before returning to Boston.

After my father graduated, we moved to Winnipeg. In the summers, we returned to Fort Frances to visit my paternal grandparents and swim in Rainy Lake. The town is on the American border and has a twin city—International Falls, Minnesota, home of Tammy Faye Bakker, the lapsed evangelist and celebrated makeup artist. At the time, you could walk across a footbridge into the United States and buy firecrackers and Hershey’s bars and attract no real interest from the customs officials on either side. That great boast—the longest unguarded border in the world—is largely gone now. It will soon require a passport to cross, shutting Canada off to the nearly 80 percent of Americans who don’t hold passports, and closing the United States to the 62 percent of Canadians who don’t carry one.

Our special relationship is in jeopardy. The remarkable trade numbers that we point to to prove our fraternity—the almost $1 billion that changes hands every day—are now overshadowed by Chinese trade. In July China became the largest exporter to the United States. As America works to seduce that vast market, Canada becomes the practical first wife, China the perfect lover. Not just an alluring trade partner, China can stand in as an ideological and military threat, another reason to keep that military economy humming. America thrives when it is in opposition to something. Alone, it begins to drift.

The relationship between Canada and the United States, which has ebbed and flowed over the years—moments of ideological harmony (the slightly maudlin duo of Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan) interspersed among friction (Kennedy called Diefenbaker a “prick”; Dief thought Kennedy was a “boastful sonofabitch”)—is again at a low ebb. Polls indicate that Canada is wary of Bush’s self-described “wartime presidency,” his flirtation with a twelfth-century Crusade, and the oddly Maoist energy of the Patriot Act that, among other protective measures, claims the government’s right to examine the books that individuals buy and borrow.

When the nations were bickering, politicians sometimes chuckled that we are like an old married couple. As the nervous war bride, we went to bed with a republic and woke up beside an empire.

There is much talk of empire these days, arguments in favour of or against, but with the tacit assumption that America has become one. Gore Vidal has argued that the American empire isn’t a recent thing, that 1947 was the year when the country rejected the limitations of a republic and embraced the seductions of empire. It was Harry Truman, a former Missouri haberdasher and perhaps the unlikeliest president in what has become a strong field, who passed the National Security Act in 1947, effectively creating a national security state and militarizing the economy. Since then, Vidal noted, America has never been without a war. Some were hot ( Korea, Vietnam), some cooler ( Iran, Chile, Angola, Grenada), one cold (the Soviet Union). There have been wars on drugs, on terrorism, and, during election years, on itself.

It was also Truman who created the cia, which quickly evolved into America’s id. Through its various incursions—Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Indonesia in 1965—and with its support for various South American dictators during the 1970s, and through the assassination plans and coup attempts, the cia was the way to maintain distance between official policy and covert action. The cia fought the dirty wars, which were ongoing, and tended to involve the spectre of communism, and tended to deal in the “moral evil and good” that William Wordsworth wrote of.

It allowed America to claim the title of both responsible global citizen and the world’s policeman. Policing embodies one of a liberal society’s great lies: we know our police need to do things that are at best unsavoury and at worst illegal in order to do their job and keep us safe. For the most part we accept this, as long as we don’t know too much about it. The key to policing is finding that line. But when that behaviour becomes institutionalized, we balk. This is a thin line, but a fundamental one. In the first case, you know that you must do evil to prevent a greater evil. In the second case, you risk becoming the greater evil. Any criticism of American military action is accompanied by the knowledge that it is keeping us safe, more or less. What did we think of the invasion of Grenada? The more paranoid among us thought it was a typo.

The invasion of Iraq has looked, at times, like a cia mission gone awry. There is no longer any need for duplicity, to maintain a gap between government policy and covert action. Talk of lesser evil has been replaced by the Old Testament absolutism that Bush favours, and, by eschewing the modesty of covert operations, the United States is exposed in a way it hadn’t been on the international stage.

When evangelist Pat Robertson announced that it was time to assassinate the democratically elected Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, he cited financial reasons. Rather than enter an expensive war (Robertson put the figure at $200 billion) with Venezuela, Robertson said, “It’s a whole lot easier to have some of the covert operatives do the job and then get it over with.” His point was taken: these days the difference between covert and overt operations is less a moral issue than a financial one. The cia is no longer the only vehicle for those unpalatable jobs that keep democracy safe, it is simply the lowest bidder.

Nineteen eighty-six: I arrived at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, DC, in July during a heat wave so profound that the tarmac had softened and a passenger jet was embedded in it, like a dinosaur descending into the tar. I took a cab into the city, one without air conditioning, and the black driver didn’t respond to my tourist inquiries. In the angry traffic, a Datsun sports car lazily cut us off. “Fucker,” the cab driver said. His name, appearing under his unhappy photograph, was Robert. At a red light we pulled up beside the Datsun and Robert yelled at him through the open passenger window. The driver rolled down his window, a bearded black man wearing a navy blue suit, blue-striped shirt with a white collar and a gold collar pin, the uniform of the ruling class in Washington at the time for both men and women, one that gave the city a look of purpose and almost complete sexlessness.

“You cut me off.”

“I did not cut you off, man.”

“You cut me off.”

“You’re dreaming, man.”

“I’m gonna fuck you up.” Robert got out and yelled over the roof of the cab. “You. Cut. Me. Off.”

“I tell you what. I didn’t cut you off. But I’m going to cut you off.” He was halfway out of his car, a muscular man who, I guessed, might be the city’s perfect citizen, walking through its moneyed corridors as a handy symbol, marching through its murderous streets as a beacon, a man who could embrace its divisions.

The light turned green, and we lurched forward, a dying Chevy that left a plume of oil. The Datsun lithely moved ahead, cut us off, and sped away. Robert put it to the mat, the underserviced engine making a sick whining sound, while he quietly repeated, seven times or so, “Gonna fuck you up, gonna…” I saw my Holiday Inn flash by. We were going sixty miles an hour through Pierre L’Enfant’s airy European urban plan. The Datsun disappeared. My driver sullenly gave up the chase, did a U-turn, and drove me back to my hotel. I asked for a receipt and he tossed a pile of blanks over his shoulder without looking.

I was in Washington to interview the cia. A spokesman was polite and unhelpful. I was researching a book that had, as a central issue, a violation of Canadian sovereignty. In the late 1950s the cia, under a clandestine cover name, financed experiments on Canadian psychiatric patients at the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal. The initial stated purpose of the program was to find out how the Koreans were brainwashing American prisoners of war. The experiments used massive doses of electroshock and drugs, and were, almost without exception, complete failures on both the medical and espionage levels. The experiments had been conducted by Ewen Cameron, a Scot who had become an American citizen and who commuted to Montreal from upstate New York each week in a black Cadillac. A group of Canadian victims had banded together in a class-action lawsuit against the cia and they were represented by Joseph Rauh, a celebrated Washington civil rights lawyer.

Rauh was a patrician white-haired liberal in his seventies who walked with a cane, and who shook hands with Ted Kennedy in the plush restaurant where we went for lunch. But the lawsuit came to nothing. The evidence was compelling, but the plaintiffs were not: mostly poor, unemployed, with lifelong problems that had almost certainly been made worse by their treatment under Cameron. The Canadian government shrugged off the invasion of sovereignty, and the assault on its homely citizens. It was a complex thirty-year-old injustice, one that could invite legal woes at home and diplomatic awkwardness with the United States.

Two television producers from Los Angeles flew up to Montreal where I then lived to discuss optioning the book for film.

“Spies, mental patients, lsd, it’s very strong,” the man said. “Very strong.”

“I like the arc,” the woman said. “Does anyone else know about this?”

Book sales being what they were, I could answer no. I never heard back from them.

The producers could see that there was little mythology to be mined here. It is a declining commodity it seems. Hollywood used to produce it in such quantity, but it is tired and disinclined now. Twenty years ago, even the invasion of Grenada yielded a major film (Clint Eastwood’s Heartbreak Ridge), proof that myth could be manufactured from whole cloth, if it came to that. Few countries have relied on mythology as stridently as the United States. If it was a breathtakingly diverse place, it still seemed possible to express its essence in the concise koan of a New Hampshire licence plate: Live Free or Die.

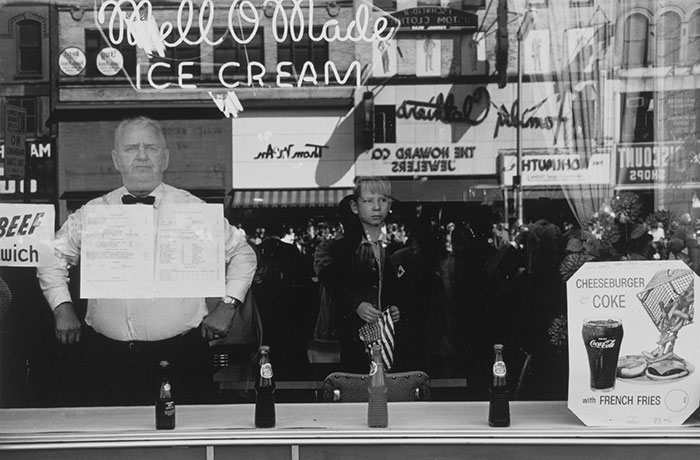

Most people experience America first through its mythology—its most effective export, which sends waves of desire across the globe for those big white teeth and endless freedoms. As a child, I embraced the country’s adolescent appetites: fast food, fast cars, willing blonds, and handguns, or at least the idea of these things. I embraced its superheroes and wisecracking private eyes, and its gift for entertainment. But my adult perspective is splintered into a hundred unrelated snapshots. Smoking a joint outside the large theatre in Seattle where I watched The Deer Hunter amid an audience of hushed veterans. Driving through South Philadelphia in a van that contained the Rolling Stones’ replacement bassist Darryl Jones and the sax player Bobby Keys, past the decayed buildings and graffiti that formed a Day-Glo narrative for several kilometres, and on to Veterans Stadium, where the band played in a driving rain and a man twitched in the mud of the infield under the gaze of a medic. Walking through Chicago Stadium, where the Blackhawks were losing to the Penguins, and seeing a placard that read Don Cherry for President.

On a hot summer night in the 1970s, when New York was just beginning its flirtation with bankruptcy, I walked through the city, my head filled with cheap wine and Ginsberg’s poetry (“America when will you be angelic? When will you take off your clothes?”), past blocks where the vegetation had overwhelmed the ruins and seemed ready to reclaim the island, where insurance fires burned in the middle distance, and I thought: there is no more marvellous place on earth. I was staying in a hotel where the lobby had been gutted, except for the elevator shafts and a wire cage over the front desk. In the daytime, I walked to the Guggenheim and MoMA and Central Park and the Broadway Deli and breathed in the secret knowledge that millions before me had.

Every visit to New York yields its Fellini moments. Exiting Bloomingdale’s to see a woman squatting over a grate, urinating, the traffic flowing around her. A man with a sandwich board laying on his back on the pavement of 53rd Street like a turtle, advertising imported suits, two for $99, and bellowing obscenities. Shania Twain playing with her band on the street outside the Plaza Hotel. During my last visit I stayed at the Millenium Hilton and looked down at the bleak chasm where the World Trade Center’s two towers had been. When the towers were finished in 1977, they were criticized as the architectural equivalent of blunt instruments, the fitting end to modernism. But the architect, Minoru Yamasaki, saw them as humane, “a living symbol of man’s dedication to world peace.” And now a new symbol will arise on the site, once more in the form of ten million square feet of office space.

In the early 1990s I went to the Grand Ole Opry, located at a giant mall-and-hotel complex away from the disturbed downtown of Nashville. I was backstage amid the calculated rusticism of its aging stars. The actress who had played Elly May Clampett on The Beverly Hillbillies in the 1960s was there, wearing her Elly May outfit, waiting to go on. She had been the source of hundreds of meticulous adolescent fantasies, which were confined almost exclusively to American actresses, among them Liz Taylor, Kim Novak, and Annette Funicello. And now here was Elly May in the flesh, pacing backstage. It occurred to me that I could ask her out, maybe go for a drink in the ersatz streetscape of the Opryland hotel. She stared at me, her eyes glazed, her thoughts elsewhere, then wandered onto the stage accompanied by banjo music and applause, out of my life forever.

The next day, I drove down to Pulaski, Tennessee, to observe a Ku Klux Klan parade, a sad, half-hearted affair that featured the economic casualties of the rust belt, their Walker Evans faces collapsed around cigarettes, their white robes and unbalanced headgear inviting ridicule in the harsh sunlight, huddling with their children as if against a storm. When they formed in 1865, they were the nation’s only organized hate group. Now there are hundreds, and the best and brightest racists have moved on, leaving the Klan for less baroque clubs. The residue of Giles County sat in their robes looking like they had been stood up on prom night. Reverend Thom Robb, the Klan’s national director, addressed the faithful: “Something terrible has happened, hasn’t it?” he asked rhetorically. “Something terrible has happened to America.” The day ended with a burning cross falling and starting a grass fire, sending the awkward Klansmen lumbering toward their pickup trucks in search of extinguishers.

Standing in the town of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, beside a railway car filled with dextrose parked at the Krispy Kreme factory, a man told me that their doughnuts had a mystical power. The chain uses the graphics and studied iconography of the 1950s as a marketing tool. “There’s more than doughnuts going on here,” the coo later told me. “It’s about memory.” They were the country’s madeleine, and one bite produced a Proustian reverie that recalled unpopulated highways and large cars and Elvis and Ike and full employment.

In Machias, Maine, I found my forebear’s signature on a town document. Arthur Hill Gillmor had come ashore here in 1786 after a mutiny on a British prison ship that was bound for Virginia. The town expelled the rest of his shipmates after a council vote, but Arthur was allowed to stay for reasons that were unstated, and he became a local schoolteacher and father to a dozen children who dispersed across the continent. Arthur himself finally left for New Brunswick.

There are times now when I am driving through North Carolina, or Maine, or Pennsylvania, or Ohio when I feel like I have lost the storyline of a film. The federation, which has been held together by cowboy iconography, faith, conspiracy, politics, blood, and belief, and divided by most of these things as well as others, seems to be without a larger narrative. It was an underlying theme of the grotesqueries in New Orleans. Myth, like patriotism, can be a dangerous commodity, but its absence offers fresh dangers.

Nineteen ninety-one: I flew into Los Angeles for the first time, descending through that thick brown carpet of air with a horrified smugness that has long since been eclipsed by Toronto’s determined emissions. A bus from the car rental company picked up a dozen of us at the airport and delivered us individually to our respective cars. The driver moved slowly through the lot, which featured Ferraris and Corvettes. I had thriftily rented the cheapest car. The driver slowed and called out each name and car. “Johnson. Jaguar.” “Sanchez. Cadillac.” When he got to “Gillmor. Tercel,” heads swivelled to watch me disappear into the city’s automotive feudalism.

I drove toward my hotel and got lost. On my right, appearing suddenly, were the mythic gates of Paramount Studios. I slowed down, leaned over and stared, weaving around my lane, a rubbernecking tourist. Horns were honked, fingers exchanged. At a red light, I felt a slight bump behind me. Then another. I looked in the rear-view mirror and saw a car full of young men wearing red headbands. They pushed against the bumper of my economical Tercel, nudging me toward the traffic that was streaming by. I turned right, stepped on the gas, and merged amid more horns, more fingers.

I was in Los Angeles to interview a celebrity, and we had a cheery lunch at a Beverly Hills hotel, surrounded by greater and lesser celebrity and the attractive assistants that follow discreetly behind, sweeping up the detritus as the parade passes. I drifted through the California landscape, taking a tour of the stars’ homes, rollerblading along Santa Monica beach, drinking bourbon in the Hotel Roosevelt with a sales rep from Little Rock when the tectonic plates that chafe politely at the San Andreas fault line shifted slightly, rattling the bottles behind the bar.

After a few days, I drove north through Santa Barbara and east over the mountains into the Santa Ynez Valley, a repository for a certain kind of American celebrity. Michael Jackson’s Neverland is there. John Forsythe, the handsome patriarch from Dynasty lived there, as did Doc Severinsen and Bo Derek. I looked at a local map and saw the Fess Parker Winery. Could it be true? The actor who had played American icons Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett was now in the wine business? I had wanted a Davy Crockett imitation coonskin cap when I was seven and my parents didn’t buy me one, an old wound. I drove to the large, well-tended building, and inside, there was Daniel Boone himself. Parker was in his late sixties, still a mountain of a man, maybe six-foot-five, with a shaggy white mane and, incongruously, two standard poodles.

I talked with Parker about his career, his life, his wine. He was a gracious, engaging man who told me about his short TV career and his entry into the world of real estate, and finally wine. He signed two bottles of Syrah with a special pen. I bought a Daniel Boone pocket knife on the way out.

Parker had seen the limitations of his iconic presence and left show business as the country began to change, to embrace anti-heroes like Steve McQueen and Paul Newman on screen. In this new torment over Vietnam, music, long hair, abortion, and education, Parker was a relic. But even in its violence and tumult, America was enviable. As a teenager, I envied its vitality and rage, the spectacle of the March on Washington, those raised fists. If campus rebellion came down to little more than middle-class kids playing at revolution, the optics were nevertheless inspiring. Perhaps the seventies were born in the violence of Altamont and ended with the angry cry of punk, a new revolution, this one imported from England.

By the time Jimmy Carter came to power in 1977, the decade had settled into fashion and buzzwords. Carter, a wise and gentle man, aged noticeably under the burden of governing that complex country. Jimmy made everyone nervous. But Ronald Reagan recalled Fess Parker’s simple aura, a big handsome man who restored the comforting simplicities of good versus bad, and evoked that Rockwell landscape that I had glimpsed as a child. He was the political incarnation of a nostalgic reverie that began in the 1980s and has been expressed architecturally (Seaside, Florida), and in the bloody-minded persistence of boomer music, in film (The Flintstones, The Honeymooners, Bewitched) and television, and fashion. Reagan’s mind was a maze of film lore and Armageddon theology, but his amiable manner conveyed that central idea: it was morning in America. It is much later now.

Nineteen ninety-six: In Port Charlotte, Florida, a centreless town of such epic sterility that I felt menaced by it, I lay awake in a tropical sweat, the kind that sometimes makes an appearance on the first page of a murder mystery. My seven-month-old daughter, who was colicky, hadn’t slept through the night in weeks. We were staying with a delusional quasi-relative in a featureless house, and during my sleepless nights within those beige walls I thought my life was disappearing in some Kafkaesque way, that I could walk through the streets and people would neither see nor hear me. My daughter wailed over the hum of the air conditioner, and I took her out to the rented car, a dark, silent Lincoln, and strapped her into her car seat. I was in my underwear and I backed out of the driveway and drove to the nearby Tamiami Trail, my daughter still wailing. Colic has buffaloed medical science to the extent that the reasons given for it have become almost metaphysical; a primal cry for all the pain that life holds. She was lulled by the movement of the car, but it had to be constant. I drove north past abc Liquors, the Tire Kingdom, the Target store, and the Wal-Mart, past the businesses dying in their wake from the comfort of peeling strip malls. Eventually the pattern repeated itself, another Target, another Wal-Mart, the way the background is repeated in cartoons. If I slowed for a red light, she woke up and cried. I began to run the red lights, moving along the subdued highway at 2:30 a.m., cool in my underwear, loving my daughter in sleep as deeply as I have ever loved.

In the day, we went to a spa with a facade that had a hint of 1950s modernism but ultimately was a little lame looking. We walked down a long cement corridor toward the change rooms and emerged in our bathing suits into a scene of unexpected beauty. There was a huge, manicured lawn of brilliant green surrounding a natural pool that was seventy-six metres across. It was fed by an underground stream, and the centre of the pool was over seventy metres deep. Along its periphery, walking in clockwise motion, were dozens of aged Floridians, moving in waist-deep water, complaining about sons who didn’t write, unmarried daughters, failing organs, spicy food, youth, and breakfast cereal. I walked among them in the curative water. Few of the walkers were unaccented: refugees from eastern Europe perhaps, survivors of pogroms or putsches, people who had, in their lives, been crowded, oppressed, and hungry. Now they were at peace in this untroubled town.

Florida has served, perhaps unfairly, as a national metaphor for complacency, though much of the United States has a Floridian feel these days. This state, with its hundreds of thousands of Canadians, even more Cubans, and an array of retired Americans who can trace their roots and accents to the steppes of Russia or the forests of Poland—a state that remains a declining source of stand-up material for a certain class of commercial comic, was the unlikely site of an allegedly stolen election. The news footage of hanging chads and screaming matches and fist fights had a banana-republic quality. The next election was allegedly stolen in Ohio, the heartland, an even more unlikely locale. One stolen election could be an aberration, two a coincidence. A third would be policy. The curious lull after those elections seemed to indicate that the country had changed in some fundamental way.

Transformation is America’s most visible industry: from poor to rich, fat to svelte, from palookaville to fame, sinner to saved. And so it made sense that Dr. Phil, the country’s most visible agent for transformation, went down to Louisiana after Katrina, where he stood in front of television cameras and interviewed men and women who had lost everything, who had been brutalized by man and nature and wondered now about the fate of their families. Phil informed the audience that it would take time to process this event, for the healing to begin. He hugged police chief Eddie Compass, who wept in Phil’s ursine embrace.

Days later, the ever-strategic Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez, arrived in New York to address the United Nations General Assembly, one day after George Bush had spoken there. Billed in one account as the successful oilman versus the unsuccessful oilman, Chavez suggested that the UN be moved out of the United States, while Bush stuck with familiar platitudes: “Either hope will spread or violence will spread—and we must take the side of hope.” The applause, by which so much in America is measured these days, was greater for Chavez.

Venezuela’s leader, a skilled if slightly obvious propagandist, worked one side of the American street as his nemesis worked the other. Chavez told community leaders that he would supply America’s poor with oil now that the Louisiana refineries were crippled. Here was an irony for the cameras, the communist president giving alms to America’s poor. Bush, for his part, told Americans they were rebuilding New Orleans with homegrown ingenuity, and reaffirmed that the American brand of freedom was God’s gift to humanity.

The bloated corpses were harvested from the canals, the water was pumped back into Lake Pontchartrain, and residents crept back, parish by parish. There were fundraising events, moments of silence, inspirational T-shirts, narrative quilts, and survivors who recounted their experiences on television. Business people dug themselves out and opened up stores and hotels, and there was talk of a new New Orleans. It would be whiter this time, not as poor, and its louche charms would be cleaned up slightly for the tourist trade. As the musicians, hustlers, pimps, chefs, and good-time Charlies eased back to the French Quarter, the roofs of houses still held their spray-painted pleas, “Please Save Us.”