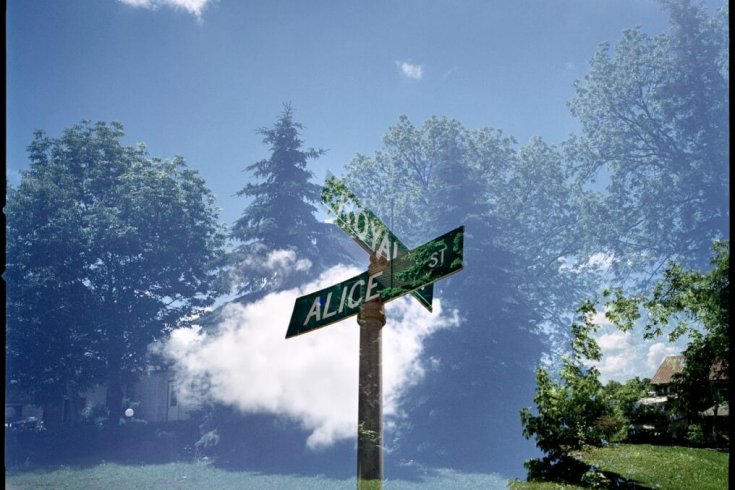

The Self-Guided Tour of Points of Interest in the Town of Wingham Relating to Alice Munro is readily available at the North Huron Museum on Josephine Street. Huron County itself is a little harder to access—a two-hour drive, heading southwest from Toronto then northwest toward Lake Huron at Kitchener or Stratford. It is off the main roads and front pages, and unfolds in miles of farmers’ fields and pushed-back bush, brick churches and fallen-down barns, villages whose shops have been boarded up, and towns short a paint job and many young people. Backward looking and inwardly inclined, its Scots-Irish Presbyterian roots old but still strong, this is countryside where the names on the cemetery stones are pretty much the same as those on the letter boxes.

Wingham, population 2,885, lies in North Huron, at the junction of Highways 4 and 86. Its residential streets stay quiet all day, and its main drag draws its blinds in early evening, aside from a grocery store, a bar, and a coffee shop with wireless Internet. Several branches of the Maitland River meet up in town, nearly encircling it like a moat, then spreading south into the rest of the county before emptying into Lake Huron near Goderich. Wingham is said to have been discovered by an Irish immigrant named Farley who built a raft in Bodmin, twenty-five kilometres downstream, and floated it north. That happened around 1840.

Alice Munro was born Alice Laidlaw on a farm outside town in 1931. She lived there until departing in 1949 for the University of Western Ontario in nearby London. Newly married to a native of Oakville, she moved first to Vancouver and then Victoria, not returning to live in Ontario until 1973, and never again residing in her hometown. But over the course of more than a dozen published books across four decades, she has remained fiercely loyal to an archetypal Ontario community and a timeless rural county—to, in effect, an imagined version of Wingham and Huron. Readers both local and international “know” these places, possibly better than any other Canadian literary landscape. Munro is, after all, the author called the “best fiction writer now working in North America” and the “equal of Chekhov, de Maupassant, and the Flaubert of the Trois Contes” by critics in the New York Times and the Globe and Mail, respectively.

Inside the North Huron Museum is an exhibit accompanied by a booklet titled Alice Munro, the Town of Wingham, and the Lives of Girls and Women. Next door is the Alice Munro Literary Garden, a former parking lot converted into a public space in 2002. The small garden features a bower, flower beds, and, nestled in a stone path, marble slabs bearing the titles of her books, including Lives of Girls and Women, the 1971 story cycle about the coming of age of Del Jordan, a budding writer who seeks a less stifling identity than the one promised by her small-town upbringing. Of the two remaining empty slabs, one will soon be engraved with Too Much Happiness, the story collection published this month. Given that Munro is seventy-eight and has claimed to be nearing the end of her career as a writer, the last stone may remain blank.

Visitors to the garden, or those hunting for the Laidlaw farm, aren’t drawn to Wingham, per se. Their fascination is with another town, called, variously, Jubilee, Hanratty, or Carstairs. The farm they want to lay eyes on belonged to another girl as well, one assigned different names in different stories. “We in no way attempt to suggest that Munro’s Jubilee is actually Wingham,” the authors of the pamphlet declare. “Despite some physical similarities, Jubilee is clearly a fictitious town existing only in Munro’s created world.”

Literary tourism is replete with such disclaimers. They speak to the power of fiction to feel at once like real life and something more perfect and eternal. Whether it is for William Faulkner’s home county of Lafayette, Mississippi, taken to be the Yoknapatawpha of his novels, or Harper Lee’s Monroeville, the presumed Maycomb of To Kill a Mockingbird, literary pilgrims travel to where their favourite authors lived and worked. They may simply be paying homage. They may also be hoping a fleeting experience of the setting that so defined the writer—the view out a study window, the bird call on a favourite walk, familiar local faces and intonations—will further deepen their experience of the books. In the case of an artist like Alice Munro, so powerfully in touch with the interiority of lives that aren’t often the stuff of fiction, the impulse to tour “her” country may be especially strong: a Munro story can alert readers to complex truths about their own hearts, and about feelings for their own landscapes they were scarcely aware of.

Early in her career, Munro herself puzzled out some complex truths about the often strained relationship between authors and their origins. In Lives of Girls and Women, her second book—a manuscript originally titled, not so incidentally, Real Life—her protagonist (and likely alter ego), Del Jordan, reacts at times with shame or contempt toward Jubilee and its people. After inheriting an incomplete regional history that had been an uncle’s passion, for example, Del, who believes that “the only duty of a writer is to produce a masterpiece,” buries the pages in a cardboard box in the cellar. She feels no remorse when they are eventually destroyed by a flood.

Lives ends, however, in an epiphany that serves as a kind of Munro manifesto, with the dawning of Del’s awareness that out of even the humblest, most seemingly stultifying circumstances can come great literature. The work she produces can be, she realizes, about a girl like her, in a town like Jubilee. Fiction, in other words, that is its own created world but is still rooted, paradoxically, in the place she wants to escape.

For my exploration of Alice Munro country, I have the Self-Guided Tour pamphlet and a road map of the county; the manuscript of Too Much Happiness; a copy of The View from Castle Rock, Munro’s 2006 fictionalization of her early life and the lives of her ancestors; and Robert Thacker’s biography Alice Munro: Writing Her Lives. Thacker, a professor of Canadian literature at St. Lawrence University in upstate New York, has offered to be available by cellphone to serve as guide. The biographer—who mentions to me that Munro paid visits to the childhood homes of authors Willa Cather and Wallace Stegner, and that she revisited Wingham with him for his book—recommended in advance that I make two specific excursions.

One is the walk Alice Laidlaw took each day from Lower Town into Wingham for school. The second is the drive south from the junction of Highways 4 and 86 through Blyth and then over to Goderich, either via the bridge at Auburn or northwest on Highway 8 at Clinton. Travelling what Thacker calls Munro’s “postage stamp of the earth” will take an hour by car. Tucked within the locale are the generalized settings for most of her great stories, along with the people, histories, and topographies essential to her literary imagination. He quotes a Munro remark about this tiny patch: “This ordinary place is sufficient, everything here touchable and mysterious.”

And of course, Huron County still contains Alice Munro herself. For much of the year, she lives in Clinton with her second husband, Gerry Fremlin, a retired geographer she met at Western. “I use bits of what is real,” she wrote years ago, during a period when her fiction was causing upset in Wingham, “in the sense of being really there and really happening in the world, as most people see it, and I transform it into something that is really there and really happening in my story.” More recently, she has written of “the countryside that we think we know so well and that is always springing some sort of surprise on us.” Doug Gibson, her long-time editor and publisher, has advised me that if the publicity-shy Munro agrees to talk, I should invite her to lunch at Bailey’s in Goderich. Reserve ahead, he said, and they’ll ensure her table is ready. It’s where she is most comfortable; where other diners know her, and the county code, enough not to make a fuss.

The Alice Laidlaw walk to school, charted in The View from Castle Rock, originates at the farm where her father, Robert, raised foxes to support his wife and three children. The modest red-brick house still stands at the end of present-day West Street, as do the outbuildings from her father’s business. The unbroken vistas of fields, along with another branch of the Maitland, are largely unchanged from seventy years ago. The Laidlaw farm sat on high ground near the western end of Lower Town Road (now Turnberry Street), an unpaved country lane so fundamental to Munro’s formation—she did her thinking along there, she told Thacker—that a photo of it graces the back jacket of the biography. A family living on Lower Town Road, the Cruickshanks, was no less important to her; the adolescent, already an apprentice writer of poems and stories, babysat for them, and entertained the children with her imagined tales. The family is gone, but that farm stands as well.

Lower Town, a scattering of houses spaced by empty lots and bush, was once home mostly to poor folk and outcasts, including prostitutes and bootleggers (Wingham was dry from 1914 to 1961). Because the river ran so high and the flatlands sat so low, floods were routine. The high ground spared the Laidlaws soaked floors, but on certain spring days Alice would have needed a boat to escape the property.

At first, her walk to elementary school was only a kilometre along the road. But her mother, aware that respectable children attended classes across the river at Wingham Public School, orchestrated a transfer, and the girl was soon crossing the Maitland at a spot where two branches met—climbing up, as Robert Thacker puts it, “the social strata” of Presbyterian Ontario.

She came to know everyone who lived along Lower Town, and then learned to register wider class differences block by block. Once over the bridge, she would have passed by the grand houses of upstanding citizens who looked down, literally and morally, on Lower Town, even though they occasionally partook of its pleasures. On Leopold Street stood the house of a great-aunt, with whom Alice stayed when the weather turned bad. “In a lot of ways, the Laidlaw farm was an island,” Robert Thacker says as I describe the property to him over the phone. Wingham, too, prey to massive snowfalls due to the lake effect, experienced spring floods, and during the worst of them the town was virtually cut off. That had to feed a novice storyteller as well: Wingham as a world unto itself, all other places vague and conjectural. “The nature of her imagination was and is organic and instinctive,” her biographer notes.

The lengthy daily walk took her from the touchable natural world to the observable human one. There, of course, lay the real complexities, and cruelties. Who did the smart, aloof Laidlaw girl think she was? “The nastiness that turns up in her fiction was real,” Thacker remarks, recalling his own sometimes chippy encounters with locals who recalled neither Alice Laidlaw nor Alice Munro fondly. “All of it fits together into shaping a sensibility of the person who used that place as a cultural specificity,” he says. The guided tour of Wingham includes the old Laidlaw farm on its secondary driving itinerary. But walking to and from it all these decades later affords a minor revelation: the setting for a literary imagination and a literary landscape in embryo.

Before departing Wingham to begin Thacker’s second excursion, I visit with several townspeople, looking, perhaps, for those familiar faces and intonations from the books. At the museum, I meet Ross Proctor, a farmer who grew up, and continues to live, ten kilometres south of town. The jovial Proctor once worked the rich land with his two brothers. “A good farmer,” he says, “leaves the land better than he found it.” As a boy, he biked those miles to school, or else stayed with relatives; like Alice Munro, whom he has known most of his life, he endured the status of hayseed. “Lower Town had its good people, and its interesting people,” Proctor remembers. He also recalls Saturday-afternoon matinees at the Lyceum Theatre on Josephine Street, and watching Doc Cruikshank, who founded Wingham’s TV and radio station, CKNX, operate the projector. Cruikshank passed away, but the theatre, long closed, remains on its original site. The station is scheduled to be shut down this month after surviving for decades as an unlikely network affiliate. Alice Laidlaw read her high school compositions on the radio there.

Alice Munro’s early stories offended certain sensibilities when they were first published in the 1950s and ’60s. In some cases, it was no more than her mentioning such open town secrets as the bootleggers and prostitutes that set people off. Other times, it was the retelling of a private family sorrow—a child scalded by a pot of water, for instance—in a fictional setting. Proctor believes the anti-Munro sentiment was exaggerated, and he later helped raise money to build the literary garden at the museum, convincing his old schoolmate to attend a series of fundraisers on his farm, which he called “AM in the PM.” Munro drove up from Clinton for the events. “She’s a regular gal,” he says approvingly. Jodi Jerome, a local historian who hails, as she jokes, from “away”—Kincardine, in Bruce County, fifty kilometres to the northwest—was curator of the museum at the time. The lingering animosities toward Munro led organizers to add a cautionary police presence to the garden’s opening ceremony. Nothing came of the worry, and Jerome believes time is slowly resolving the matter. “They’re not around any longer,” she says of certain people, and their resentments.

Jerome, who has met Munro twice, once at a reading, the other time at the museum, approves of her low-key presence in the county. “You live up here,” she says, “it’s what you do. You don’t get given, or go looking for, kudos.” A young intern at the museum admits that, were Munro to visit the room dedicated to her life and work, she might not recognize the author.

Verna Steffler, president of the Wingham and District Horticultural Society, tells a story about visitors’ desire to find the writer amid the landscape. Steffler first came to the town from the Sarnia area to work as a nurse; one of her early patients was Anne Laidlaw, Munro’s mother, who died of Parkinson’s in 1959. Steffler was working in the garden with another volunteer one day when she noticed a literary pilgrim from Pittsburgh staring at her co-worker, a tall woman with grey hair. “Are you Alice Munro? ” the American finally asked. Steffler ended up driving the disappointed admirer to the Laidlaw farm to begin her tour.

The notion that Alice Munro might be found tending her own literary garden isn’t so crazy. Munro once told the Globe and Mail about a time she volunteered as a waitress during the Blyth Theatre festival. When a customer asked her if a glamorous-looking woman seated at another table might be the famous local author, Munro happily confirmed his suspicion. Last year, by contrast, when the festival mounted a production based on one of her stories, she declined to attend. She was willing to be in Blyth as a country woman helping serve meals, but not as a famous author accepting accolades. The unwritten Huron County code of behaving like regular folk probably informed her decision. She seems to need to be at once embedded in the landscape, working the garden she has been growing since her first book, 1968’s Dance of the Happy Shades, and invisible.

On my way south on Highway 4, past the hamlet of Belgrave, near Ross Proctor’s farm and a cemetery containing Laidlaw ancestors, and then down into Blyth, a thought continually recurs: if a walk in Wingham enriches a reader’s appreciation of Munro’s imaginative sensibility, then a drive along this country highway may speak to the defining qualities of her prose—its flintiness and deliberate plain-speech, the cadences steady regardless of the often abrupt tonal shifts from light to dark. Or better: if an Alice Munro paragraph could be rendered into a landscape, it might look like these country roads. The lonely farmhouses, some happy, some unhappy, spaced by flat, dark fields. The oversized churches reduced to a single service per week. Historical landmarks for villages long ago rendered ghosts. A footbridge marker for the Black Hole, at Piper’s Dam, and private roadside pleas that Abortion Stops a Beating Heart. The Maitland River, meandering like a persistent, inescapable theme.

Many of the stories in Munro’s new collection begin and end in old age, arcing back to a defining incident from childhood. “I am amazed sometimes to think how old I am,” the protagonist in “Some Women” declares at the start. “I can remember when the streets of the town I lived in were sprinkled with dust in summer, and when girls wore waist cinches and crinolines that could stand up by themselves, and when there was nothing much to be done about things like polio and leukemia.” After unravelling a devastating tale—still another open secret of small-town life—the story repeats its mantra: “I grew up, and old.” The pattern is evident elsewhere in the collection, and indeed throughout her recent books. Often, too, the occurrence from the past has greater narrative urgency than present-day events. Nearly always, that past belongs to Huron County.

In an earlier conversation, Robert Thacker remarked that as Munro has aged she has tended to return not only to the county, but to a specific period: the 1930s and ’40s, when she was Alice Laidlaw walking from Lower Town into Wingham. The movement lately has been still further back in time, into the nineteenth century, and the roots of her people, and of the landscape. From her younger self, she is shifting into her pre-self, almost, a kind of genteel erasure of that famous author.

Thacker made another, more speculative point about Munro’s ongoing need to be present in Huron County. Of the stories in Too Much Happiness that are clearly situated in the area (the lengthy title piece is set in nineteenth-century Europe), the two most harrowing touch down along its margins. The opening tale, “Dimensions,” about a woman who must gain back her spirit after her mentally ill husband murders their children, references the “away” town of Kincardine. In “Free Radicals,” another vulnerable woman, a widow living in an unnamed village, outwits an intruder who has committed a triple homicide. He spares her life but steals her car, only to die later in an accident near the village of Wallenstein, to the east of Huron County. In Munro’s mature imagination, Thacker speculated, to dwell inside the Huron County zone I am presently driving—the Wingham-Blyth-ClintonGoderich nexus—is to be protected, up to a degree, by those attachments to family, place, and landscape. To be outside the zone is to be exposed to more random perils.

Alice Munro delights in the story of mistaken identity at the literary garden. “Maybe I should go work in my garden,” she says. “But I’d have to insist on being paid minimum wage.” She laughs at her own joke, bending forward in amusement. While she is a lean, striking woman, her grey hair curly and her smile dazzling, her entrance into Bailey’s restaurant on the Goderich town square merits just a few nods. I am already seated at the anointed table, which is identified only by a copy of The View from Castle Rock on a cabinet next to it. Without prompting, a waitress brings a glass of white wine and a bottle of fizzy water, and then leaves us alone as well. Gibson remembers a previous lunch where they ended up asking the restaurant staff for help selecting a book cover. He is at the table, too, at once curious about my literary drive and protective of his author.

Munro, who has battled cancer, is funny and alert, her informality and good cheer possibly designed to put interviewers at ease and yet keep them at arm’s length. (She had also, it turned out, recently learned that she had won the Man Booker International Prize, valued at nearly $115,000. It was a secret she had to keep until the public announcement two weeks later.) I had made my intentions known in advance, and she is content to chat about the curious business of people visiting “her” Wingham and “her” Huron County. “I do it myself,” she says of literary tourism, “hoping to find some trace of the writer. But when I think of my own work being pinned down… ”

One literary outing in particular mattered to her. William Maxwell was both an editor at The New Yorker and a gifted novelist. After he died in 2000, she drove to Lincoln, his hometown in Illinois and the setting for many of his books. Finding no official recognition that this esteemed writer was a native son, Munro wrote a note complaining about the neglect and slipped it under the door of the local tourist board office. “There’s always disappointment when you see the reality,” she says of such visits. “You want to get close to something you can’t ever get close to.” But she also understands the impulse. Literary tourism, she decides, stands at the “intersection of the actual world with the huge imaginative world” of the work itself.

Still, she isn’t sure what visitors will find in Huron. “It’s not particularly close to my own life,” she says of her fiction. “Everything gets switched around on the page.” But then Munro, who hesitates to probe her own creative processes—“I don’t know,” she replies to several questions about her own intersections—admits she has been over the ground of Wingham so often that she isn’t quite sure “what is purely imaginary” in the stories. “All those things happened to me before I was ten years old,” she says of her awakening.

When I suggest that authors puzzle over the question of the actual versus the imagined nearly as much as readers do, and so may be fated to be equally conflicted about the degree of reality in their books, she decides that the literary pilgrimage, if undertaken largely to “pay your respects,” is just fine. But then she adds a very Alice Munro caveat about visitors to Huron County: “What I really want them to care about is the work. Not me.”

Over the two days of my visit, I’ve kept thinking about how Munro continues to live and work in this intimate, if not claustrophobic, setting. Well known, both from The View from Castle Rock and from interviews in recent years, has been her passion for exploring what one character calls “our part of the country” with her husband. Their focus has been as much on the geography of the region as on its residents, whether living or deceased. She and Gerry Fremlin spend days mapping drumlins and moraines and seeking forgotten crypts. “We go looking for things we hardly dare tell people about,” she admits. Then she immediately confesses one such search: for a car graveyard in nearby Holland Township. Having spotted it once before, they spent a fruitless weekend trying to find the site again. Her vivid description of car carcasses sunken and overgrown, another kind of mark on the land, suggests the search will continue.

Alice Munro, in short, is also a visitor in Huron County. Where others bring copies of Lives of Girls and Women and study the Self-Guided Tour of Points of Interest in the Town of Wingham Relating to Alice Munro, she and Gerry study specialized maps and books with such titles as The Physiography of Southern Ontario. These various pilgrims share in common the land itself, so fecund it can produce and abide writers and their stories, cemeteries and their crypts, tumbledown barns and car graveyards. “So you have to keep checking,” that same Munro character from Castle Rock explains of the land, “taking in the changes, seeing things while they last.”

At lunch with the apparently ageless author at Bailey’s in Goderich, it is hard to imagine things not lasting. But a question to Munro about whether she views these landscapes differently now than, say, a quarter-century ago, brings out the artist who has been observant and clear eyed about life and death alike for a long time—possibly since she was that smart girl in Lower Town. Not content with my time frame, she arcs back to a much older memory to explain her sense of time and change. On a highway between Blyth and Clinton is a field she recently recalled as having once hosted an abundant orchard. The orchard, which had likely been harvested by Laidlaws, probably perished during the winter of 1934. She was only three at the time, and living up the road in Wingham, but the memory of its extinction, either directly observed or passed along as a tale, lives inside her still.

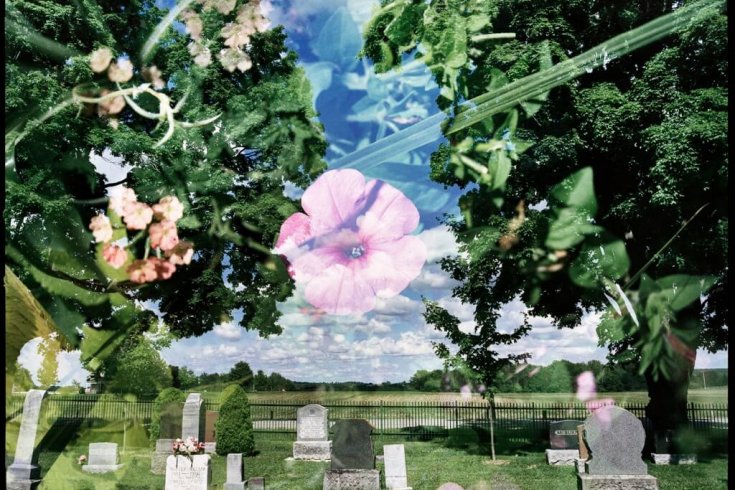

Next, she volunteers that she and Gerry will shortly be rooted in the ground near Blyth as well. They have already purchased burial plots in the town cemetery—in the heart of the heart of Alice Munro country, safe from harm—and though she prefers to go unrecognized now, she will be content to receive visitors later on. “Come see me there,” Munro says of her final resting place. Her laugh is high and sharp, and full of a particular kind of mischief.