Our little plane rattles, pushed by a stiff tailwind toward Uranium City, in the farthest reaches of northwestern Saskatchewan. Hundreds of metres below us, buried in the Canadian Shield under vast forests of black spruce and icy lakes, lie deep pockets of uranium ore, which feed nuclear reactors around the world. But Uranium City now exists as a contradiction: a town of 100 called a “city.” Its namesake, uranium, is one of the most valuable commodities on the planet, though the first place in Canada where the ore was mined is now a near-ghost town, out of range from the giant mining operations that have followed the ore deposits hundreds of kilometres to the south. Uranium promised the world a clean, high-powered future, but in a harbinger of what other mining communities may face, this town has been left with a legacy of radioactive dust blowing out from its abandoned mines.

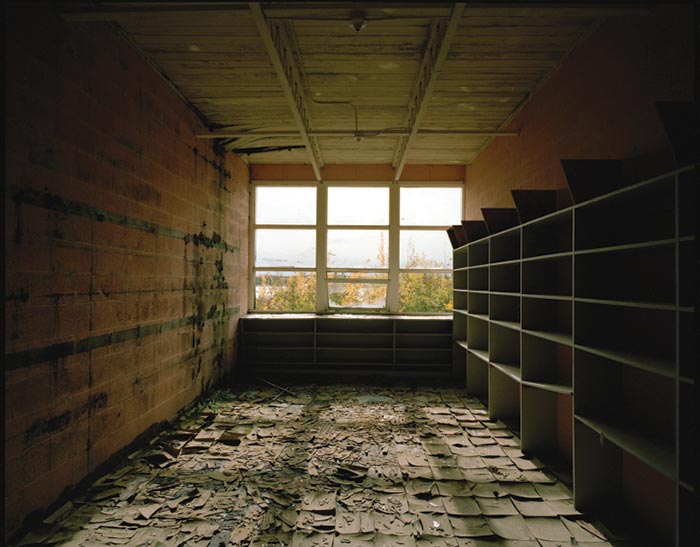

At twilight, we land on a crumbling airstrip, with no answer to our radio calls. In 1946, at the dawn of the Cold War, when large deposits of uranium were unearthed nearby, dozens of mines sprouted downward, pulling in hundreds of workers from across Canada. By 1952, the “city” was booming, a Jetson-like symbol of the world of tomorrow. Streets were optimistically christened Fission Avenue and Nuclear Road, and the school, Candu High, paid homage to the first Canadian-designed nuclear reactor. The town’s population peaked at 5,500. But over the next thirty years the precious ore slowly ran out, and by 1982 the last mine closed. Entire neighbourhoods were abandoned. Cars were left to rust where they were last parked. The movie theatre closed. The police left. Last year the hospital shut down.

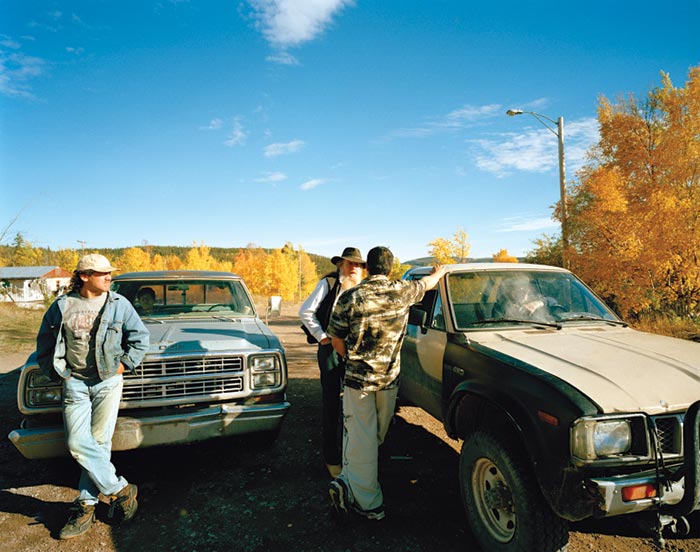

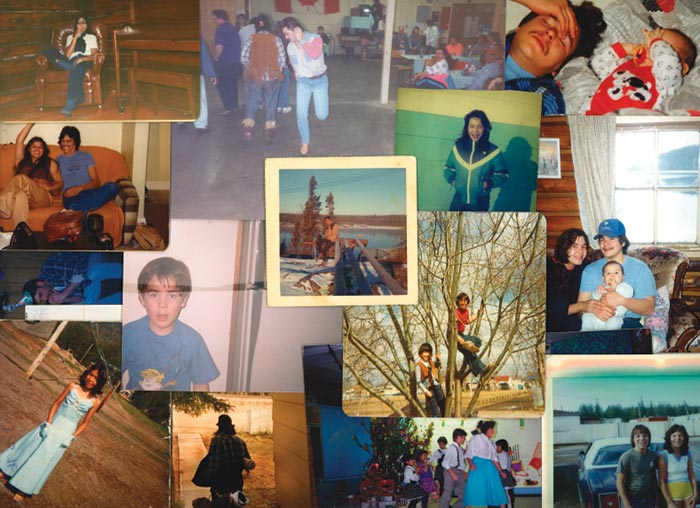

That night, as I walked the weakly lit gravel roads, the sky glowed with the curling, green waves of the northern lights. I heard a door slam, and in the distance what sounded like drunken laughter. An old pickup truck crunched along the road, then roared off into the darkness. Yet strangely, there was a sense of occasion in the air. As I soon discovered, it was the fiftieth wedding anniversary of Billy and Regina Shott, one of the few couples still living in this unlikely place. They were renewing their vows, and friends and family had been trickling in from all across the north. The town’s population would double, or even triple, with the arrivals. A few locals said it was the last big bash the town would likely ever see. But who knows, the ground still yields surprising gifts. Recently, so-called rare-earth minerals were dug up north of the city. Essential in the manufacturing of television screens, rechargeable batteries, and hydrogen-powered cars, the discovery of these minerals raises the possibility of another mining boom. But anyone who has ever lived in Uranium City knows that predicting the future is like digging blindly in the dirt.