The government of Canada gave my family our first apology, for the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II, in 1988. I was seventeen, and I don’t remember any of it. I had other things to worry about. My mom had just left my dad, Bob Miyagawa. She’d cried and said sorry as my brother and I helped her load her furniture into the back of a borrowed pickup. Her departure had been coming for a while. At my dad’s retirement dinner the year before, his boss at the Alberta Forest Service had handed him a silver-plated pulaski, a stuffed Bertie the Fire Beaver, and a rocking chair. My mom, Carol—barely forty years old and chafing for new adventures—took one look at the rocking chair and knew the end was near.

Three months after she left, on September 22, Brian Mulroney rose to his feet in the House of Commons. The gallery was packed with Japanese Canadian seniors and community leaders, who stood as the prime minister began to speak. “The Government of Canada wrongfully incarcerated, seized the property, and disenfranchised thousands of citizens of Japanese ancestry,” he intoned. “Apologies are the only way we can cleanse the past.” When he finished, the gallery cheered, in a most un–Japanese Canadian defiance of parliamentary rules.

The clouds may have suddenly parted in Ottawa; the cherry blossoms in Vancouver may have spontaneously bloomed. I missed it all. It was graduation year. Every day after school, I worked at West Edmonton Mall, diving elbow deep in Quarterback Crunch ice cream so I could save up for a pool table. Weekends, I visited my mom at her new place, a small apartment within walking distance of the tracks by Stony Plain Road.

Up until then, and perhaps to this day, being half Japanese had just been something I used to make myself unique. A conversation starter. A line for picking up girls. The internment my dad and 22,000 others like him suffered was something to add to the story. It increased the inherited martyr value.

I didn’t get many dates.

Four years earlier, when Brian Mulroney was leader of the Opposition, he’d asked Pierre Trudeau to apologize to Japanese Canadians. Exasperated, Trudeau shot back, “How many other historical wrongs would have to be righted? ” It was Trudeau’s last day in Parliament as prime minister. He finished his retort with righteous indignation: “I do not think it is the purpose of a government to right the past. I cannot rewrite history.”

Trudeau must have known that the apology door, once opened, would never be closed. Mulroney might have known, too. Redress for Japanese Canadians was the beginning of our national experiment with institutional remorse—an experiment that has grown greatly over the past twenty years, intertwining itself with my family’s story.

Ilike to look at the glass as half full: my parents’ divorce was not so much a split as an expansion. They both remarried, so my kids now have more grandparents than they can count. And I’ve gained the most apologized-to family in the country—maybe the world.

I watched Stephen Harper’s apology for Indian residential schools with my dad’s wife, Etheline, on a hot night in the summer of 2008. Etheline was the third generation of her Cree family to attend an Indian mission school. She went to Gordon Residential School in Punnichy, Saskatchewan, for four years. Gordon was the last federally run residential school to be closed, shutting down in 1996 after over a century in operation.

When I talked to my mom in Calgary afterward, she casually mentioned that her second husband, Harvey’s father, had paid the Chinese head tax as a child. Harper apologized to head tax payers and their families in 2006.

I was aware that my family had become a multi-culti case study, but when I realized the government had apologized to us three times it went from being a strange coincidence to a kind of joke. (Q: How does a Canadian say hello? A: “I’m sorry.”) Soon, though, I started wondering what these apologies really meant, and whether they actually did any good. In seeking answers, I’ve mostly found more questions. I’ve become both a cynic and a believer. In other words, I’m more confused than ever before. I’m no apology expert or prophet. I’m so sorry. All I can offer is this: my apology story.

In the fall of 2008, I travelled from my home in Whitehorse to Vancouver. The National Association of Japanese Canadians had organized a celebration and conference on the twentieth anniversary of Redress. It rained as I walked toward the Japanese Hall on Alexander Street in East Vancouver, in what was once the heart of the Japanese community. In the distance, giant red quay cranes poked above the buildings along Hastings, plucking containers from cargo ships anchored in Burrard Inlet. The downpour soaked the broken folks lined up outside the Union Gospel Mission at Princess and Cordova, a few blocks from the hall. Some huddled under the old cherry trees in Oppenheimer Park, beside the ball field where the Asahi baseball team, the darlings of “Japantown,” played before the war.

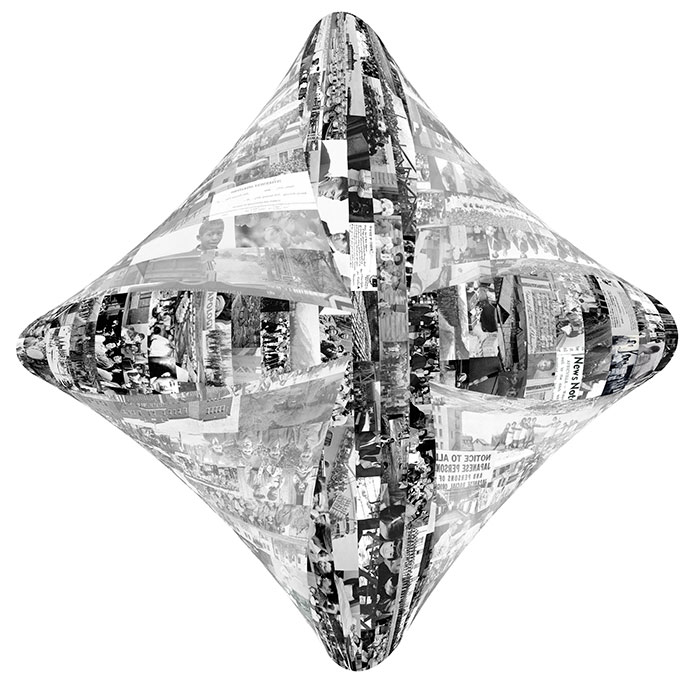

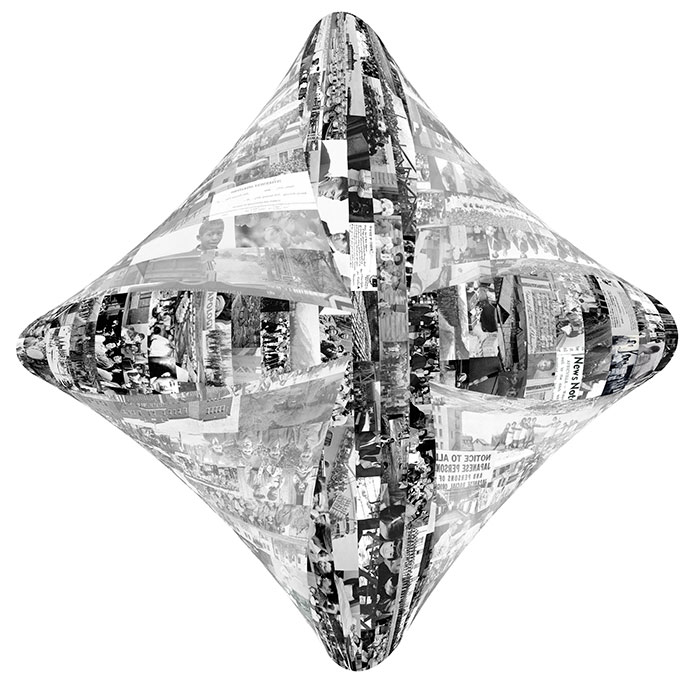

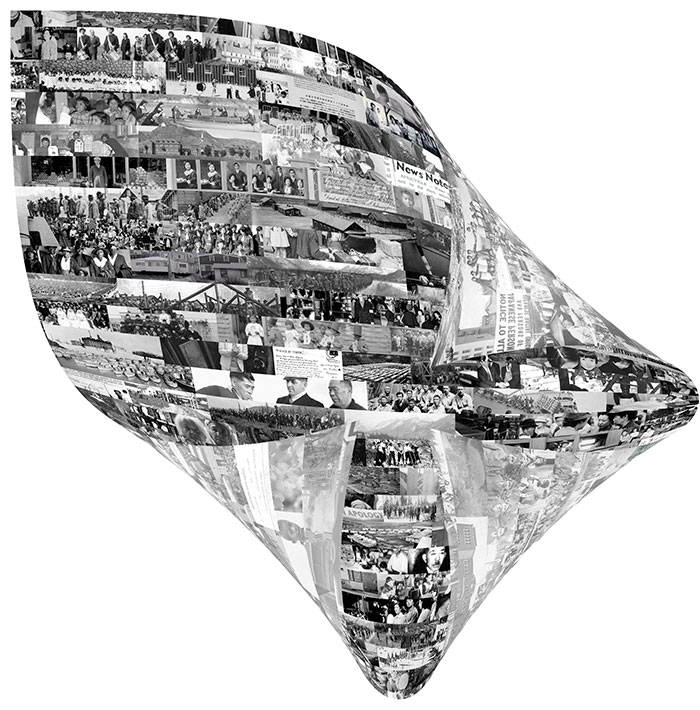

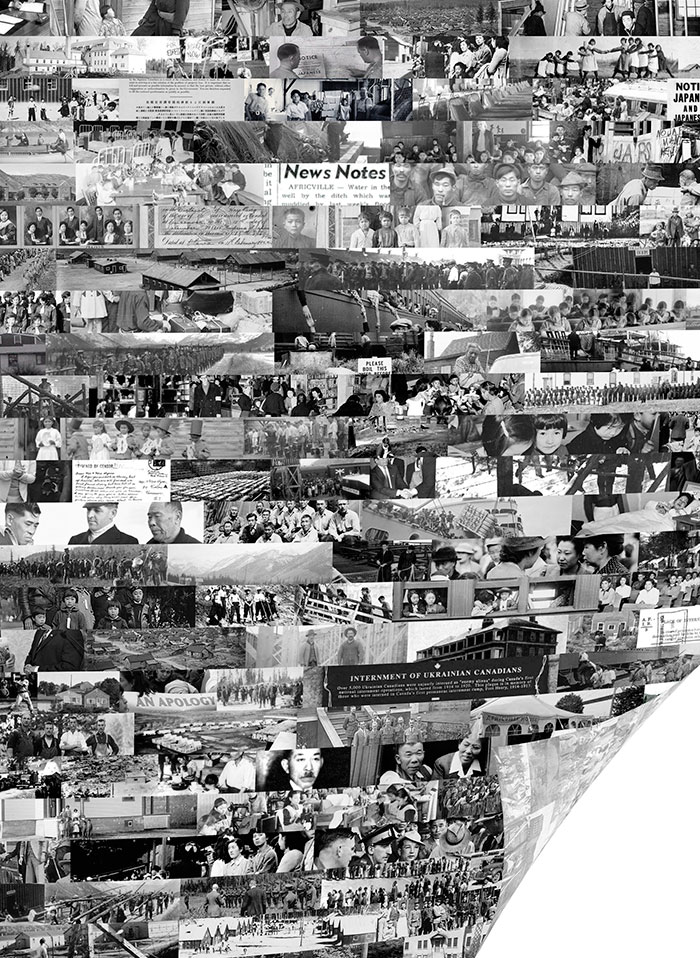

Inside the hall, a few hundred people milled about, drinking green tea and coffee served from big silver urns by blue-vested volunteers. The participants on the first panel of the day, titled Never Too Late, took seats on the wide stage at the front. They represented the hyphenated and dual named of our country: a Japanese-, Chinese-, Indo-, Black, Aboriginal, and Ukrainian-Canadian rainbow behind two long fold-out tables. Their communities had all been interned, or excluded, or systematically mistreated. Apology receivers and apology seekers. A kick line of indignation, a gallery of the once wronged. (A Japanese-, Chinese-, Indo-, Black, Aboriginal, and Ukrainian-Canadian all go into a bar. The bartender looks at them and says, “Is this some kind of joke? ”)

In the fictional world of Eating Crow, a “novel of apology” by Jay Rayner, the hottest trend in international relations is something called “penitential engagement.” To deal with the baggage from the wars, genocides, and persecutions of the past, the United Nations sets up an Office of Apology. The protagonist of the novel, Marc Basset, is hired as Chief Apologist, partly because of his tremendous ability to deliver heartfelt apologies, but also because of his “plausible apologibility.” His ancestors captained slave ships, ran colonies, slaughtered natives, and waged dirty wars. Backed by a team of researchers and handlers, Basset circles the globe, delivering statements of remorse.

Penitential engagement is closer to reality than you’d think. The Japanese government has made at least forty “war apology statements” since 1950. All of Western Europe remembers German chancellor Willy Brandt’s famous Kniefall in 1970, when he fell to his knees on the steps of the Warsaw Memorial, in silent anguish for the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. During the past twenty years, Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi has apologized for the colonial occupation of Libya, South African president Frederik W. de Klerk has apologized for apartheid, and the Queen has issued a Royal Proclamation of regret to the Acadians in the Maritimes and Louisiana. In 1998, the Australian government began its annual National Sorry Day for the “stolen generations” of aboriginal children. In 2005, the US Senate apologized for its failure to enact federal anti-lynching legislation. And both houses of Congress have now passed apologies for slavery.

At the 2001 UN World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, held in Durban, more than 100 countries called “on all those who have not yet contributed to restoring the dignity of the victims to find appropriate ways to do so and, to this end, appreciate those countries that have done so.” Working toward this goal is the International Center for Transitional Justice in New York, which “assists countries pursuing accountability for past mass atrocity or human rights abuse.” As if in response, jurisdictions across Australia, the United States, and Canada are passing apology acts designed to allow public officials to apologize without incurring legal liability.

Concerned about our precious self-image as a peacemaking, multicultural country, Canada has been making every effort to lead the sorry parade. In addition to the residential school and Chinese head tax apologies, the federal government has also now said sorry for the Komagata Maru incident, when a ship full of immigrants from India was turned away from Vancouver Harbour, and established a historical recognition program “to recognize and commemorate the historical experiences and contributions of ethno-cultural communities affected by wartime measures and immigration restrictions applied in Canada.” And we became the first Western democracy to follow South Africa in establishing a truth and reconciliation commission, for the residential schools.

Not surprisingly, other groups have come knocking on Ottawa’s door. Among them are Ukrainian Canadians, on behalf of those interned during World War I, and the residents of the bulldozed Africville community in Halifax, now a dog park. Some who have already received an apology clamour for more, or better. Harper’s Komagata Maru apology was issued to the Indo-Canadian community outside Parliament. Now they want the same as every other group: an official, on-the-record statement.

I sat down on a plastic-backed chair in the deserted second row. Seconds later, an old Nisei, a second-generation Japanese Canadian named Jack Nagai, plunked down beside me. He sighed and lifted the glasses hanging around his neck to his face. “Gotta sit close for my hearing aid,” he said, then looked at me and grinned. I pulled out a notebook, and he watched me out of the corner of his eye, fingering the pen in his breast pocket.

Black scuffs, I wrote. The pearly walls and floor of the Japanese Hall auditorium were marked and streaked. A fluorescent light fifteen metres above my head flickered and buzzed. The hall had a school gym wear and tear to it. Jack noticed my scribbling and jotted down something on the back of his program.

The brown spots on his bald head reminded me of my Uncle Jiro, who passed away suddenly in 2005 at the age of seventy-seven. As it turned out, Jack was from Lethbridge as well, and had known my uncle from the city’s Buddhist Church. My Uncle Jiro, “Jerry” to his non-Japanese friends, had helped the blind to read, bowled every Sunday, and kept a meticulous journal of the prices he’d paid for groceries and the sorry state of his golf game. He’d been a bachelor, mateless and childless, like several others on my dad’s side.

Those few of us in my family who now have kids have Caucasian spouses, so our strain is becoming less and less Asian. The Miyagawa name may disappear here with my two sons, and with the name would go a story seeded a hundred years ago.

My grandmother and grandfather farmed berries on three hectares of rocky slope in Mission, BC, starting in the 1920s. They were their own slave-drivers, labouring non-stop to clear the land and get the farm going. Grandmother produced the workforce, delivering a baby a year for a decade. My dad was near the end, the ninth child of ten. By 1941, the Japanese controlled the berry industry in BC. My grandparents’ farm expanded and flourished.

Then came Pearl Harbor, war with Japan, and the dislocation of more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians from the West Coast. On a spring day in 1942, my dad and his family carried two bags each to the station and boarded a train bound for the sugar beet fields of southern Alberta. They never made it back to Mission. The Japanese Canadians weren’t allowed to return to BC until four years after the war was over, so the family instead settled in Lethbridge. Dad moved away soon after he came of age, and ended up in Edmonton, where I was born.

For my dad, the apology was pointless. Like many others in the Japanese Canadian community, he had already turned the other cheek. Shikata ga nai, the saying goes—what’s done is done.

I admire and marvel at his ability to let go of the past. He even calls his family’s forced move across the Rockies a “great adventure.” For a ten-year-old, it was a thrill to see the black smoke pouring from the train engine’s stack as it approached the Mission station.

Mist softens a train platform in the Fraser Valley. Last night’s rain drips from the eaves of the station, clinging to the long tips of cedar needles. All over the platform, families are huddled together by ramshackle pyramids of suitcases. Children squat around a puddle on the tracks, poking at a struggling beetle with a stick. A distant whistle; their mother yells at them in Japanese; they run back to stand beside her. Their father stands apart, lost in thought. He’s trying to commit to memory the place where he’d buried his family’s dishes the night before, in one of his berry fields a few kilometres away.

Clickety-clack. Clickety-clack. A screech of brakes, a sizzle of steam. The train pulls in, the doors open, each one sentinelled by a Mountie with arms crossed.

The families become mist, along with their suitcases and the Mounties. Everything disappears except the train. It’s quiet. An old conductor in a blue cap sticks his head out the window. No need for tickets on this train, he says. Step right up. Welcome aboard the Apology Express.

The conference began, and Jack and I leaned forward to hear. The panellists took their turns bending into low mikes, paying homage to the hallowed ground zero of apologies. Chief Robert Joseph, a great bear of a man in a red fleece vest, hugged the podium and said, “The Japanese Canadian apology was a beacon.” Everyone at the tables looked tiny, posed between the high black skirting framing the stage and the minuscule disco ball that hung above them.

The people telling the stories of their communities were the same ones who had put on their best shoes to walk the marbled floors of Parliament, who had filed briefs for lawsuits. They spoke in the abstract—reconciliation, compensation, acknowledgement—and kept up official outrage as they demanded recognition for their causes. “We have to remember, so it will never happen again” was the panel’s common refrain. After an hour, Jack’s eyes were closed, and he’d started to lean my way. I could hear soft snoring from the other side of the room, where a group of seniors slumped and tilted in their chairs.

This wasn’t what I’d come to hear either. After studying and listening to official expressions of remorse to my family and others, after reading the best books on the subject (The Age of Apology; I Was Wrong;On Apology;Mea Culpa), I’d come to believe that government apologies were more about forgetting than remembering.

I righted Jack as best I could, and snuck out the back of the hall for some fresh air.

I’ve always imagined that my mom met Harvey Kwan in a room full of light bulbs. They both worked for the Energy Efficiency Branch of the provincial government. She wrote copy for newsletters; he did tech support. In my mind, Mom would watch the way Harvey methodically screwed the bulbs into the bare testing socket. She appreciated his size. Not quite five feet tall, my mom likes her husbands compact (though she did dally for a time with a rather tall embezzler from Texas). She was further attracted to Harvey’s quiet voice, his shy smile as he explained wattages and life cycles. Perhaps they reached for the same compact fluorescent and felt a jolt as their fingers touched.

Mom and “Uncle Harv” were both laid off soon after they started dating, so they moved from Edmonton to Calgary, closer to their beloved Rockies, and became true weekend warriors, driving past the indifferent elk on Highway 1 to Canmore and Banff to hike and camp and ski. Mom was afraid of heights; Harv took her hand and led her to the mountaintops.

Harvey’s father had sailed to Canada aboard the Empress of Russia in 1919, at the age of fourteen. He paid the $500 head tax, then rode the CPR with his father to the railroad town of Medicine Hat, on the hot, dry Alberta prairie. Around the time he became an adult, in 1923, the Canadian government passed a Chinese Immigration Act, which remained in force for twenty-five years. Under the act, no new Chinese immigrants could come to Canada, so a young bachelor like him could only have a long-distance family. He managed to sire three sons with his first wife in China during that time, but she never made it to Canada, dying overseas. He eventually took a second wife, Harvey’s mom, who had to wait several years before she could enter the country. In the meantime, she lived unhappily with Harvey’s father’s mother, probably waiting on her like a servant.

And that’s all Harvey knows. He doesn’t know about his father’s life, those twenty-five years away from his first wife and their children, then his second. He doesn’t know his grandfather’s name. He doesn’t know what his grandfather did. He doesn’t know where the man is buried. They never spoke of that time.

Mr. Speaker, on behalf of all Canadians and the Government of Canada, we offer a full apology to Chinese Canadians for the head tax and express our deepest sorrow for the subsequent exclusion of Chinese immigrants… No country is perfect. Like all countries, Canada has made mistakes in its past, and we realize that. Canadians, however, are a good and just people, acting when we’ve committed wrong. And even though the head tax—a product of a profoundly different time—lies far in our past, we feel compelled to right this historic wrong for the simple reason that it is the decent thing to do, a characteristic to be found at the core of the Canadian soul.

—Stephen Harper, June 22, 2006

Apology comes from the Greek apo and logos (“from speech”), and as every first-year philosophy student who reads Plato’s Apology knows, it originally meant a defence of one’s position. But somewhere along the line, it became a Janus word, adopting its opposite meaning as well. Rather than a justification of one’s position or actions, it became an admission of harm done, an acceptance of responsibility. When Harper spoke on the head tax, you could see both faces of the word at work: Those were different times. We’re not like that now. We should, in fact, be proud of ourselves. Pat ourselves on the back. Reaffirm our goodness today by sacrificing the dead and gone.

Rather than bringing the past to life, statements like these seem to break our link with history, separating us from who we were and promoting the notion of our moral advancement. They also whitewash the ways in which Canadians still benefit from that past, stripping the apologies of remorse. Rendering them meaningless. Forgettable.

Iwasn’t the only one taking a break from the conference. I followed a Japanese Canadian woman with short grey hair down the street to Oppenheimer Park, watching from a distance as she placed her hand, gently, on the trunk of one of the old cherry trees. I later learned that these were memorial trees, planted by Japanese Canadians thirty years ago. The City of Vancouver had been planning to chop them down as part of a recent redevelopment scheme, but the Japanese Canadian community rallied and saved them (though the old baseball diamond will still be plowed under).

I arrived back at the hall in time for lunch. Ahead of me in line was the author and scholar Roy Miki, one of the leading figures in the movement for Japanese Canadian redress and a member of the negotiating committee for the National Association of Japanese Canadians. Miki was an “internment baby,” born in Manitoba in 1942, six months after his family was uprooted from their home in Haney, BC. He laughed when I told him about my family and, intrigued, pulled up a chair beside me for lunch. He had neat white hair, parted to one side, and wore blue-tinted glasses. We balanced bento boxes on our knees, and he told me something that astounded me: the negotiators hadn’t wanted an apology very badly.

“We wanted to shine a light on the system—to show its inherent flaws,” he said. “Our main concern wasn’t the apology or the compensation. The real victim was democracy itself, not the people.” What those pushing for redress wanted was an acknowledgment that democracy had broken down, and that people had benefited from the internment of Japanese Canadians. They wanted to change the system in order to protect people in the future.

Miki remained wary of government expressions of remorse, concerned that the emotional content of apologies—the focus on “healing”—distracted from the more important issue of justice. “Now the apology has become the central thing,” he said. “It allows the government to be seen as the good guy. But there’s a power relationship in apologies that has to be questioned; the apologizer has more power than the apologized-to.”

Mulroney, in his apology to Japanese Canadians, said the aim was “to put things right with the surviving members—with their children and ours, so that they can walk together in this country, burdened neither by the wrongs nor the grievances of previous generations.” Both the victimizer and the victim are freed from their bonds. Japanese Canadian internment “went against the very nature of our country.” With the apology, so the redemption narrative went, Mulroney was returning Canada to its natural, perfect state. Cue music. Roll credits. The lights come up, and all is right with the world again. I find the storyline hard to resist, especially when the main characters are long gone. But of course not all of these dramas took place once upon a time.

My dad met his second wife, Etheline Victoria Blind, at a south Edmonton bingo. Yes, he found a native bride at a bingo, in front of a glass concession case where deep-fried pieces of bannock known as “kill-me-quicks” glistened under neon light.

I was working for an environmental organization at the time. Like most Alberta non-profits, we depended on bingos and casinos as fundraisers. Dad was one of our A-list volunteers. He was retired, reliable, and always cheerful, if a bit hard of hearing. Etheline, on the other hand, was on the long-shot volunteer list. She was the mother of the high school friend of a colleague. I didn’t know her, but I called her one night in desperation.

I don’t remember seeing any sparks fly between Dad and Etheline. He was sixty-five at the time, and not seeking to kick at the embers of his love life. But Etheline invited him to play Scrabble with her, and so it began.

Dad and Etheline had a cantankerous sort of affair, from my point of view. They lived separately for many years—Dad in a condo on Rainbow Valley Road, Etheline in an aging split-level five minutes away—but moved gradually toward each other, in location and spirit, finally marrying a few days after Valentine’s Day, eight years after they met. I flew down from Whitehorse with my son, just a year old then. He was the only person at the wedding wearing a suit, a one-piece suede tuxedo.

And so Etheline became my Indian stepmother.

Stephen Harper’s apology to residential school survivors was a powerful political moment. You had to be moved by the sight of the oldest and youngest survivors, side by side on the floor of Parliament—one a 104-year-old woman, the other barely in her twenties. The speeches were superb, the optics perfect. Yet personally, I felt tricked. Tricked because the apology distilled the entire complicated history of assimilation into a single policy, collapsing it like a black hole into a two-word “problem”: residential schools. Here was the forgetful apology at its best. By saying sorry for the schools, we could forget about all the other ways the system had deprived—and continued to deprive—aboriginal people of their lives and land. The government had created the problem, sure, but had owned up to it, too, and was on its way to getting it under control, starting with the survivors’ prescription for recovery. If they were abused, they merely had to itemize their pain in a thirty-page document, tally their compensation points, stand before an adjudicator to speak of their rape and loneliness, and receive their official payment. All taken care of.

And yet. And yet.

Etheline, I apologize. I knew you for ten years and never really knew where you came from. I’m educated, post-colonial, postmodern, mixed race, well travelled, curious, vaguely liberal, politically correct. “You’re the most Canadian person I know,” I’ve been told. And yet I never once asked you about your time in residential school. I never really related until that night, after we’d watched Harper’s shining moment, that powerful ceremony—and I’d watched how it moved you, felt the hair on my arms rise and a shiver in my back when we talked late and you told me how your grandfather was taken from his family when he was four, the same age my oldest son is now; told me how he’d never known his parents, but relearned Cree ways from his adopted family and became a strong Cree man even after his own children were taken away; how he’d raised you when your mother couldn’t; how you were in the mission school, too, for four years, and your grandfather wouldn’t let them cut your braids, and you’d feel the cold brick walls with your hands, and the laundry ladies would only call you by your number, and you would stare out the window toward the dirt road that led away from the school and cry for your Kokum and Meshom. I never knew. Or if you told me, I only listened with half an ear. And I apologize again, for bringing it all up, for writing down your private pain. But I know we need to tell it again and again. It has to be there; it has to get into people’s hearts.

And here I make an apology for the government apology. For whatever I feel about them, about how they can bury wrongs in the past instead of making sure the past is never forgotten, about how they can use emotion to evade responsibility, they have indeed changed my life. They’ve made me rethink what it means to be a citizen of this country. They’ve brought me closer to my family.

Near the end of the conference, the woman with short grey hair stood up and told a story. After World War II, when she was a schoolgirl, she’d one day refused to read out loud from a textbook with the word “Jap” in it. She was sent home, where she proudly told her father what she’d done. He slapped her across the face. The apology, she told everyone at the hall, had restored her dignity. The conference ended the next day, and I returned home with something to think about.

It’s summer as I write, almost a year since the conference, and the apologies have kept coming. The state of California apologized for the persecution of Chinese immigrants last week. Thousands of former students of Indian day schools, feeling left out of the residential school apology, filed a statement of claim at the Manitoba legislature yesterday.

I’m sitting on the beach of Long Lake, just outside Whitehorse. Though it’s hot outside, the water here always stays cold, because the summer’s not long enough to heat it. Still, my two boys are hardy Yukoners, and they’re running in and out of the water, up to their necks. I watch their little bodies twist and turn, then look at my own thirty-eight-year-old paunch and search the sky. What will we be apologizing for when my children are adults? Temporary foreign workers? The child welfare system?

Tomio bumps into Sam, knocking him to the ground. Sam cries. “Tomio,” I tell my oldest, “say sorry to your brother.” “Why? ” he asks. “I didn’t mean to do it.”

“Say sorry anyway,” I reply.

We say sorry when we are responsible and when we are not. We say sorry when we were present or when we were far away. We are ambiguous about what apologies mean in the smallest personal interactions. How can we expect our political apologies to be any less complicated?

Along time ago—or not so long ago, really, but within our nation’s lifetime—another train hustled along these tracks: the Colonial Experiment. She was a beaut, shiny and tall. Ran all the way from Upper Canada; ended here in this lush Pacific rainforest. The Colonial Experiment was strictly one way, so it’s up to the Apology Express to make the return trip.

Watch as we go by: a Doukhobor girl peeks out from under her house, her head scarf muddy. The police officers who took her sister and her friends away to the school in New Denver are gone and won’t be back for another week. A Cree boy, hair freshly shorn into a brush cut, stares out the window of a residential school in the middle of the Saskatchewan grasslands, watching his parents’ backs as they walk away. A Japanese fisherman hands over the keys to his new boat. A Ukrainian woman swats the mosquitoes away, bends to pick potatoes at Spirit Lake, and feels her baby dying inside her. A Chinese man living under a bridge thinks about his wife at home and wonders if he’ll see her again.

But take heart: at every stop on the way back, someone important will say sorry for their lot. Just like the man in the top hat on my son’s train engine TV show, he’ll make it all better, no matter how much of a mess there’s been.

All aboard. If you feel a little sick, it’s just the motion of the cars. Close your eyes. Try not to forget.