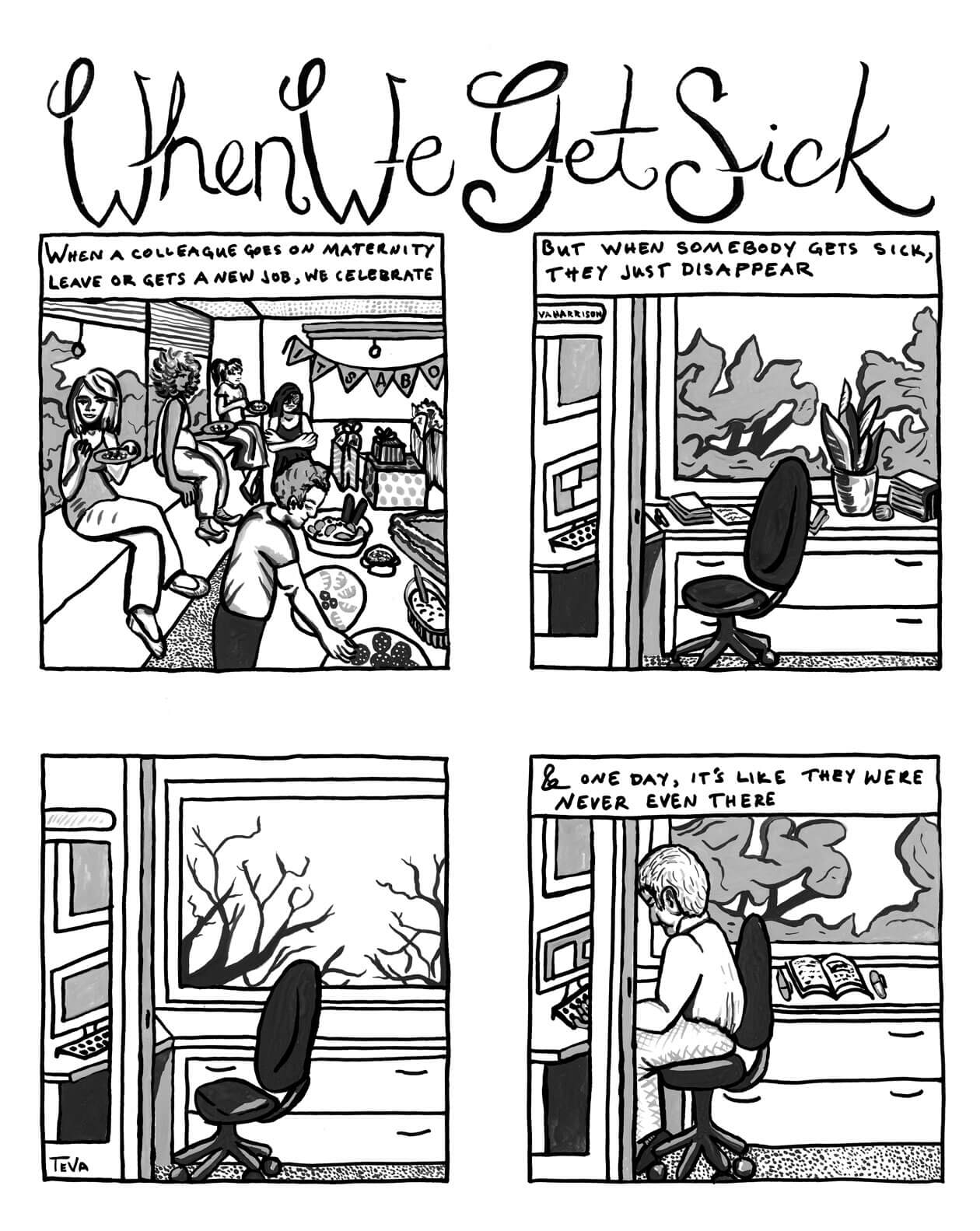

1. When We Get Sick

It doesn’t feel right to celebrate when somebody gets sick. Picture this: You’re in a boardroom at work, balloons taped to the whiteboard, sheet cake festooned with icing-sugar flowers sweet enough to hurt your teeth, bowls of chips, two-litre bottles of pop. Everybody gathers expectantly, watching the clock. In walks the guest of honour. But this time, it’s not a blushing pregnant woman from accounting or a jovial retiree. No. Instead, I pad into the room wearing ill-fitting layers of cotton hospital robes, steadying my feet by holding onto a rolling stand, IV bag bouncing with every shambling step.

And there goes the party.

Now blink that image away, because it will never happen. I don’t go wandering the city in hospital gowns like a horror-movie escapee. For me, the horrific is all under my skin. I look amazing. I’ve lost forty pounds, thanks to cancer, and people I haven’t seen in a long time often ask me my secret. I tell them they don’t really want to know. My struggle now is stopping the loss.

When we get sick, we disappear. But it’s not like maternity leave or retirement. We plan for those things. Getting sick is never on any five-year plan. And when someone’s illness is sudden, there are more important considerations than organizing files for a hand-off, let alone ordering a cake and scribbling a few nice words on a card.

How do we celebrate the people who disappear but are not yet dead? How do we celebrate their contributions?

Illness is nothing to celebrate. We don’t have craft enough to bend language to accommodate the breadth of living and dying, working and failing, and always falling short.

We’re meant to check our personal life at the door when we show up for work. We’re meant to be dispassionate and dry; our work relationships are supposed to have the necessary distance that comes with hierarchy. We’re expected to keep it professional.

When I got sick, I tried to work. For a couple of weeks, my denial was enough to get me through the day. But it lasted only weeks. With time, the reality of my terminal diagnosis hit me like a tropical storm, all-encompassing and rushing. I sat in my office and cried, until I thought I was being too disruptive. Then I realized that I had to go on leave. I was useless at my desk.

Months passed. My colleagues got by just fine, which made me feel both proud of my team and totally redundant. Eventually, I told my boss that I wasn’t going to be able to come back for a while and that she should think about bringing in someone new.

But it was still hard for me when she did.

As much as I want that job filled by an amazing and effective person, I still want that person to be me. And deep down, I want to have been better than my replacement.

A distance can open—a disconnect between what we expect of a sick colleague and what she can deliver. Even when people are compassionate, the gap grows, as the abilities of the sick and the healthy no longer align. This creates a certain kind of loneliness—of being alone among others. This is the loneliness of the ill: our pace slows down as others pull away.

With each additional weight strapped to our legs—a new schedule imposed by hospitals, side effects from treatment, atrophying muscles, a clouded intellect—our career aspirations move further out of reach. These aren’t changes that inspire celebration.

No balloons. No sheet cake. No gilded pins. No speeches.

When we get sick, we disappear.

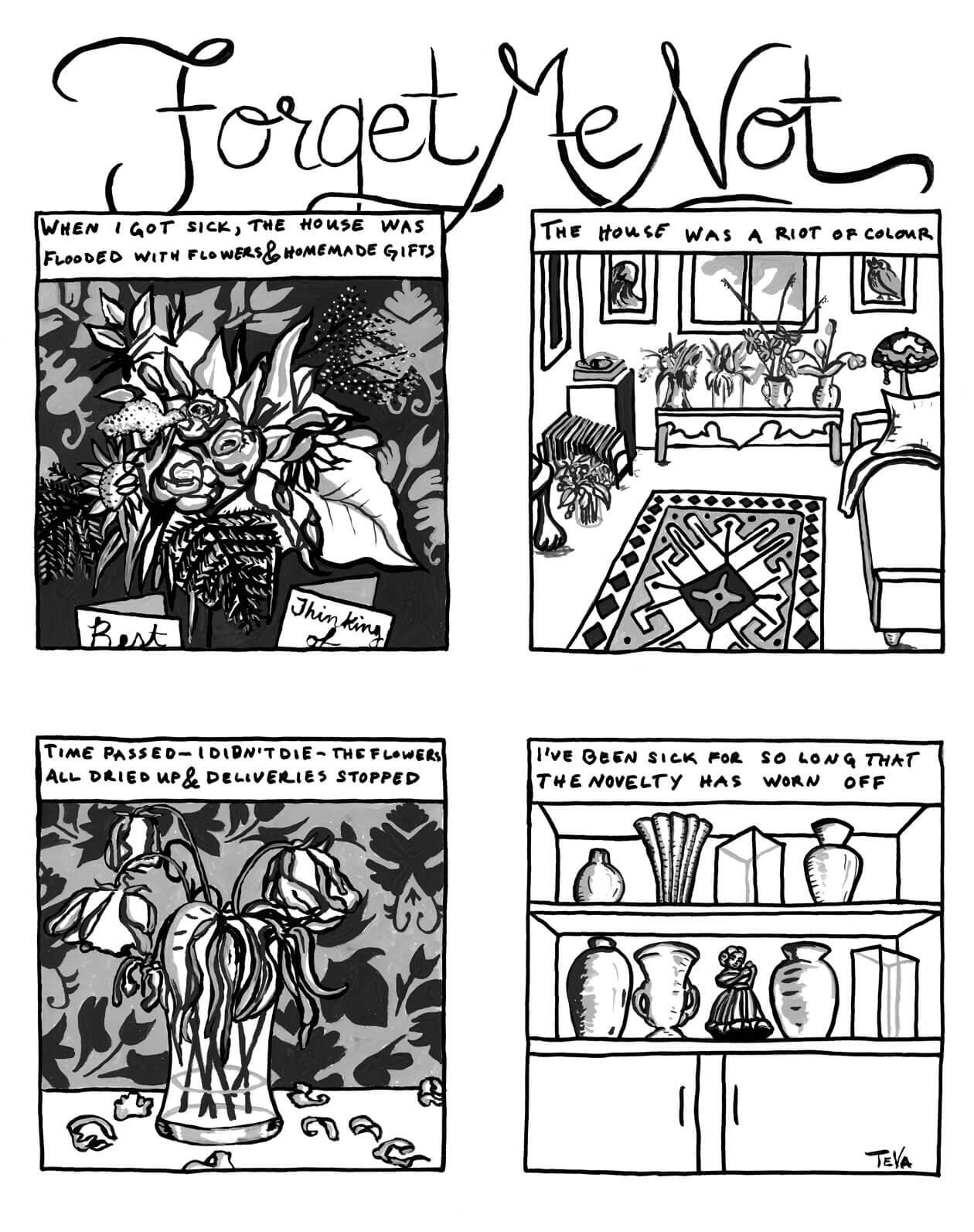

2. Forget Me Not

After I got sick, the mail brimmed with beautiful cards and doodled letters. Knocks on the door meant flowers or a wonderful handmade present. People brought soup and magazines, hugged me, and then disappeared. The impulse to do something took many forms, each an expression of a wonderful person’s best self.

The postal service struggles to remain relevant, delivering mostly bills and flyers, but I looked forward to the day’s mail. It made me feel loved. I tried to resist the urge to tear all the jelly bean-coloured envelopes open at the door, instead carrying them inside to savour on the sofa with a cup of tea. I loved what the choice of card told me about each sender, and the sweet sentiments they shared. It was the best part of my day.

But things changed. I’ve been sick a long time. And if I’m lucky, I’ll be sick a long time yet. I need to conserve my energy, and so do my supporters. And I will need so much more help when this gets worse.

For now, with my disease more or less stabilized by drugs through a clinical trial, I am able to take care of myself. But that’s not the same thing as caring for myself. I need other people to care for me. And it’s not fair to ask my husband to be all things—and yet more and more, I ask him to be just that, and he is.

I don’t need the gorgeous home-cooked food right now, although it’s delicious and appreciated. A time will come when I need much more of that kind of help. So, in fear of burning out my supporters before I’m incapacitated, I try not to ask for much.

And since I’m not asking, people are timid. They don’t want to get in the way or make me feel bad when I say, “No, thank you.” They don’t want to risk saying the wrong thing and upsetting me. Because who knows what to say when somebody they love is dying—and dying, not now, but on some indeterminate later date?

There is no right or wrong thing to say. Language becomes a labyrinth of well-intentioned missteps that offers scarce moments of clarity. Click-bait articles with titles such as “12 things never to say to someone who has cancer” list highly personal pet peeves, none of which necessarily applies to the cancer patient near you. Everyone’s cancer is personal.

The stakes are too high. We don’t want to upset the people we love. So we pull back and away. It’s no wonder that so many people find it easier to say nothing at all.

And so the shower of thoughtful gestures dries to a trickle, and fear calcifies the silence. And I, at the moment not in acute crisis, give up my place in the front of your mind. I yield because I know there’s something more pressing.

While you’re out in the world, among the people and the glorious mess of living, I’m still here—alone, more often than not. And a tiny little voice in my heart is whispering as loud as it can: “Please don’t let me be forgotten.” Not now, not yet.

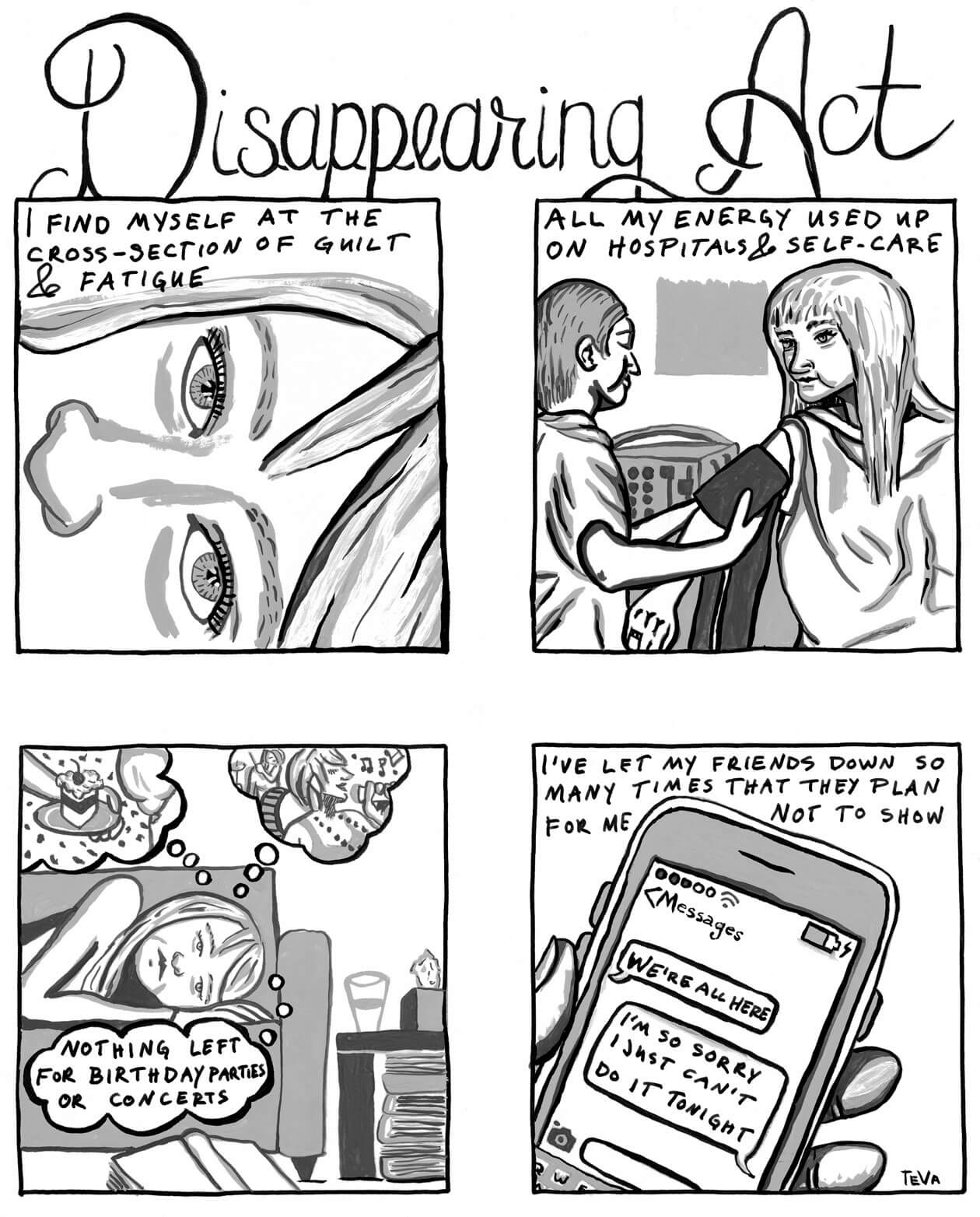

3. Disappearing Act

With all the amazing people I know, I have many opportunities to celebrate. Any given week, I would like to attend a few of these fine gatherings: birthday parties, weddings, bridal showers, baby showers, bar nights, art shows, rock shows, operas, dinners, lunches, walks in the park, opportunities to catch up over tea. There is so much I want to do, witness, take in, and learn from.

I used to fill my days to overflowing. And at the end of a full night, I’d collapse onto my bed, happy and enriched, a chatterbox spilling words across the pillows at my love.

But now my energy is both finite and mercurial. All the plans I make come with a caveat: I’ll come if I am able. It’s a terrible way to plan, and it feels unfair to my friends. Sometimes I can give decent notice, but my cancellations are usually last minute.

But what choice do I have, when a day at the hospital might mean that I have only enough energy to get myself into bed, teeth brushed and contact lenses out?

So my friends no longer expect me to show up. They plan for my absence. But when I am able to be there, the looks of love and joy are the best kind of sustenance. I can feed off a single interaction for weeks.

Sometimes, my husband arranges for a back-up friend, someone who could use our second ticket for a play or concert should I be unable to attend. He makes apologies on my behalf, and when he comes home, he recites a litany of names and passes along good wishes and enthusiastic promises of future hugs.

Of course I would choose the people and the events every time, if I could. But hospital visits aren’t optional, and I require what feels like an absurd amount of rest. I have to choose self-care over socializing and be respectful of my body’s limitations, or I may no longer have a self to care for.

So I live with the fear that I am allowing myself to disappear, to lose my social relevance. I worry that one day, the invitations will simply stop, and I’ll be erased from the list of people who make a party fun. I used to be a lot of fun.

My voracious appetite for living has defined me as long as I can remember. As my illness forces me to pare back, I don’t just feel as though I am becoming less busy—I am becoming less myself.

This is how cancer erodes my identity. It saps my energy and pulls me back from the centre of the crowd. It forces me to make choices with my head rather than my heart. And this stripped-down, leaner, more clarified person is what it leaves behind. I may be disappearing, but I’m still here.

I have been reduced. But not to nothing. Not yet.

This appeared in the May 2016 issue.