The city of Toronto is stumbling toward the end of 2011 mired in a deep civic funk. Mayor Rob Ford, a renegade small-c conservative from the suburban ward of Etobicoke North, bulldozed his way to victory a year ago on a simplistic pledge to slash municipal waste. His mantra: “Stop the gravy train.” While he has yet to identify instances of reckless spending, he has ordered city officials to extract almost $800 million from Toronto’s $9-billion operating budget, the sixth-largest public purse in Canada. This punishing and potentially ruinous process may entail shuttering libraries, firing police officers, and scaling back everything from snow removal to grass cutting to transit. Municipal services—such as public housing, environmental advocacy, and even zoos—that don’t conform to the mayor’s narrow vision of local government may be eliminated, privatized, or significantly reduced.

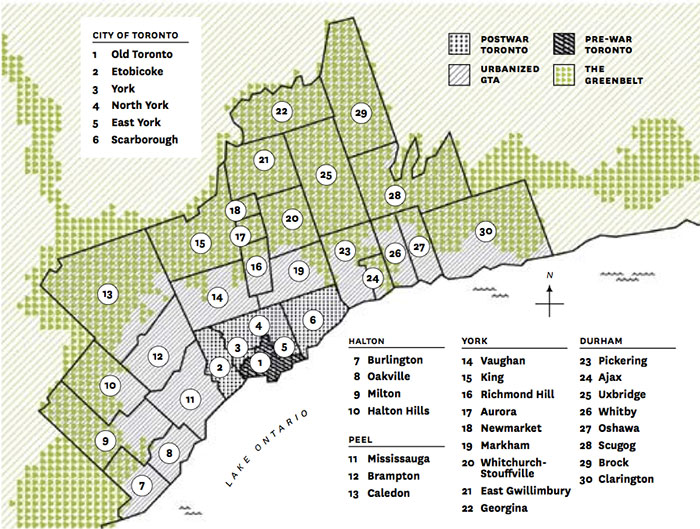

Toronto’s woes, however, go well beyond the mayor’s fiscal populism. The Greater Toronto Area—a 7,100-square-kilometre expanse of 5.5 million residents who live in a band of municipalities extending from Burlington to Oshawa to Newmarket—finds itself increasingly crippled by some of North America’s nastiest gridlock, congestion so bad it costs the region at least $6 billion a year in lost productivity. Sprawl, gridlock’s malign twin, continues virtually unchecked, consuming farmland, stressing commuters, and ratcheting up the cost of municipal services. Without reliable funding, transit agencies can barely afford to modernize, much less expand, straining the GTA’s roads and highways to the bursting point.

The GTA’s problems have a social dimension as well. With some of the country’s highest real estate prices—now more than $450,000 for an average single-family dwelling—affordable rentals remain scarce, while tens of thousands of families who earn as little as $20,000 a year languish on waiting lists for often-substandard subsidized housing. In Toronto’s so-called “inner suburbs” (the city proper consists of an older core dating to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, surrounded by a ring of “outer suburbs” built between 1945 and the early 1970s), poverty has become more prevalent and concentrated. And ethnic: while Toronto has more foreign-born residents than any metropolitan region in the world, many newcomers struggle to find decent work, even if they arrive bearing university degrees.

Not that there is nothing to recommend Canada’s largest city; on the contrary. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Toronto was transformed from a joyless provincial backwater into an energetic, cosmopolitan capital and is now one of the world’s “alpha” cities. Its mixed economy emerged from the 2008 credit crisis and recession in good shape, sustaining hundreds of comfortable residential neighbourhoods, as well as dozens of thriving retail strips on older main streets such as Danforth Avenue, College Street, and Queen Street East. Crime rates remain relatively low (Statistics Canada ranks Toronto third lowest of Canada’s thirty-two census metropolitan areas on its 2010 crime severity index, well below Regina and Montreal, for example), while tolerance for immigrants, the poor, and a wide range of ethno-cultural groups runs high. Toronto is also an excellent place to be gay, get sick, eat out, go to school, work as an artist, see live theatre, attend film festivals, walk in a ravine, borrow library books, publish newspapers, launch indie bands, develop smart phone apps, conduct biomedical research, and raise capital for mining ventures. For these and other reasons, the GTA attracts 100,000 new residents every year.

But even as many of the world’s other megacities, including regional rivals like Boston and Chicago, prepare for an era of breakneck global urban expansion, Toronto persists in thinking small and acting cheap. Should the rest of Canada care? Yes, because the GTA is the country’s economic hub, accounting for one-fifth of its gross domestic product; New York, by contrast, produces just 3.3 percent of the United States’ national income. Canadian politicians typically refuse to acknowledge the importance to the country of its largest metropolis, opting instead to pander to provincial anti-Toronto sentiments. But tens of billions more in tax revenues flow out of the GTA than come back in the form of services and public sector investment, which means GTA wealth subsidizes government services across Canada, including health care and social security. So whether they love or loathe Toronto, all Canadians have a stake in its well-being. If Toronto fails, all Canadians will feel the pain.

Question: who’s in charge? Answer: no one

After World War II, thousands of Canadians streamed home from the battlefields of Europe, got married, and launched the baby boom. Like many cities, Toronto was short of places for these new families to live. To manage the growth pushing outward from its pre-war boundaries, the Ontario government embarked on an innovative experiment in urban governance. In 1953, it created the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, a two-tier federation that ultimately consisted of six local municipalities—Etobicoke, York, North York, Scarborough, East York, and the City of Toronto—overseen by a council of mayors and aldermen. The idea was simple: use the commercial core’s economic heft to underwrite the cost of urban infrastructure on the periphery. And it worked. Over the next thirty years, Metro, as the federation was called, built a modern, relatively compact city that was admired throughout the world for its approach to municipal government.

But that was then. Today municipal government across the GTA is a cumbersome, expensive, balkanized embarrassment, the legacy of ill-considered decisions by successive Ontario governments. The problems began in the early 1970s, when Bill Davis’s Progressive Conservatives decided to impose the two-tier approach on the rural townships, a ring of suburbs now known as the 905, outside Metro’s borders. Andrew Sancton, an expert on municipal government at the University of Western Ontario, describes that decision as “the original mistake.” The result, unique in North America, is that Toronto is surrounded by a ring of large, powerful municipalities—Mississauga, Brampton, Oakville, Richmond Hill, Markham, Vaughan, and Ajax-Pickering—that compete with the city for private and public investment.

Jack Dylan

Jack DylanAfter 1976, when the provincial Parti Québécois came to power, Canada’s economic centre of gravity shifted west from Montreal, along Highway 401 toward Toronto, spurring waves of growth. By the end of the 1980s, the government of Ontario recognized that the region had morphed into a huge metropolitan area criss-crossed by increasingly irrelevant local boundaries. In 1994, NDP premier Bob Rae asked Anne Golden, then head of the United Way and now president and CEO of the Conference Board of Canada, to chair a task force to determine how best to manage growth across the GTA. Her team’s sage solution: eliminate Metro and the other 905 regional municipalities in favour of a single Greater Toronto Council, with a mandate to plan and oversee such services as transportation, waste management, and economic development. The task force also recommended preserving the larger, lower-tier municipalities (for example, Toronto, Mississauga, and Oshawa), so they could continue offering residents access to local services like parks and planning. In effect, Golden was telling the province to reinvent Metro, but on a much broader canvas.

Conservative premier Mike Harris, elected in 1995 to reduce government via his Common Sense Revolution, ignored the Golden task force, choosing instead to amalgamate Metro and its local municipalities while leaving intact the 905 two-tier governments established in 1973. Although Harris claimed his reforms would facilitate more streamlined decision-making, the result has been anything but. Thirteen years after amalgamation, many Torontonians feel increasingly alienated from a giant municipal bureaucracy that favours one-size-fits-all solutions.

The city’s forty-five-member council is riven by chronic factionalism that pits the older central city against the postwar suburbs. Council meetings go on for days and often become mired in tortured arguments about issues as inconsequential as councillors’ office expenses. And so strong is the incumbency advantage that many councillors remain in office long after their best-before dates.

Despite Harris’s ambition to reduce government, the GTA remains staggeringly over-governed, with 244 municipal office holders, including twenty-five mayors. By comparison, New York, with 8.3 million residents, is governed by fifty-one councillors, five borough presidents, and just one term-limited mayor. Yet the GTA has no democratically elected regional council with a mandate to focus on wider issues, such as economic development and transportation planning. The Ontario government has been reluctant to establish such a body, for fear of creating a powerful political rival or being accused of giving the GTA preferential treatment. So while regional governments oversee vast metropolitan areas in Berlin, São Paulo, and Greater Vancouver, the government of Ontario has yet to learn a crucial lesson in urban expansion: when cities spill over their existing borders, managing growth becomes more vital than ever.

Flat broke (sort of)

Since taking office a year ago, Mayor Ford has characterized Toronto’s finances as “a mess” and has derided the civic bureaucracy as “garbage.” As he said repeatedly during the election, the city doesn’t have a revenue problem; it has a spending problem. But the truth is far more complicated. Like many cities that grew quickly in the postwar era, Toronto’s municipal infrastructure—roads, sewer mains, transit lines, and public housing units—requires billions of dollars in upgrades and repairs. Enlightened politicians in cities like New York and London have recognized the need to invest in growth, even if it means raising taxes or imposing user fees. But Rob Ford is taking Toronto in the opposite direction: deliberately—and perversely—impairing its ability to prepare for the future.

Ken Greenberg, a Toronto urban designer who has worked in New York and Boston, argues that parsimony has hampered the city’s political culture for over a century. “The expression I use is ‘too rich for our blood,’” he says. Some of the city’s enduring achievements—a dramatic water treatment plant and a crusading public health department—stand out because they were built by visionary civil servants who defied the enduring stinginess of Toronto voters. A more typical story: Toronto’s 1912 decision to reject a $7-million proposal to build a subway up Yonge Street. The city would be radically different today, in all likelihood served by a much more extensive subway network, had those now forgotten politicians taken the long view.

During the decades of postwar growth, Metro spent heavily on infrastructure, justifying its borrowing costs as the price of progress. But in the 1980s and 1990s, as development took off north and west of Toronto, the municipalities of Vaughan and Markham enthusiastically pursued beggar-thy-neighbour tax policies that enticed businesses to avoid or flee Metro and its higher commercial and industrial taxes. The result: a slow but painful decline in Metro’s non-residential tax revenues; growing tracts of fallow land; and fewer jobs in the inner suburbs, such as Scarborough and East York.

But the most punishing blow—the big bang, from a municipal revenue perspective—came in 1997, when the Harris government, having rammed amalgamation through, decided to relieve municipalities of the burden of funding education in exchange for “downloading” the costs of transit, public housing, and parts of welfare. Harris said the exercise would be “revenue neutral,” and for suburban municipalities with less transit and fewer social services, it was. But in Toronto, with its aging subway system and tens of thousands of crumbling public housing units, downloading proved disastrous. The Toronto Transit Commission took a particularly hard hit. The province had subsidized transit operations and capital needs since the 1960s. Now, when much of the system’s infrastructure was beginning to show its age, the provincial government was absolving itself of any financial responsibility. With almost half a billion riders per year, the TTC was North America’s most cost-effective transit system. But without adequate provincial funding, the city had no choice but to cut service and stop planning for expansion.

Other factors have conspired to impair Toronto’s financial well-being. Amalgamation increased the city’s labour costs, as public sector unions merged and then negotiated higher wages. The amalgamated city’s first mayor, Mel Lastman, compounded the fiscal crunch by freezing property taxes, so from 1998 to 2000 revenues rose more slowly than expenses like fuel, electricity, labour settlements, borrowing costs, and construction materials. Meanwhile, the Harris government made matters worse by ignoring the recommendations of a panel, led by former Scotiabank chair Cedric Ritchie, which recognized that businesses were fleeing the city and urged the government to equalize the property tax rates for education between Toronto and the surrounding 905 municipalities.

The city’s spending and borrowing grew under Lastman’s successor, David Miller, who persuaded Harris’s successor, Dalton McGuinty, to reduce the impact on ratepayers by increasing provincial grants and gradually shifting financial responsibility for welfare and disability benefits back to the province. The federal government kicked in a portion of the gas tax and the GST as well. But the new revenues haven’t addressed the growing structural deficit. Debt service is now the second-largest line item in Toronto’s budget (after payroll and pension obligations), and the city still faces years of multibillion-dollar outlays on repairs to aging infrastructure, including transit. According to a 2010 study by the Toronto Board of Trade, the annual operating shortfall could exceed $1.1 billion by the end of this decade.

To solve the problem, the board proposed privatization, new procurement procedures, and pension cuts. But experts in municipal finance such as Enid Slack, an economist at U of T, point out that many global cities rely on an array of alternative revenue sources: for example, sales taxes, hotel occupancy levies, and parking fees. In 2008, Mayor Miller introduced two such taxes, on vehicle registrations and land transfers, which generated roughly $300 million annually. But the newly elected Mayor Ford threw out the vehicle tax as soon as he took office, and he still threatens to eliminate the land transfer tax, which brings in $250 million a year. He also froze property taxes, even though residential property taxes are already lower than in the neighbouring 905 municipalities. Ford’s proposed spending cuts will only harm Toronto’s quality of life, and absent a more enduring solution the city could face a fiscal catastrophe of the same magnitude that nearly bankrupted New York in the late 1970s.

From A to B the hard way—even though there’s a better way

Toronto responded to postwar growth by creating an impressive rapid transit system comprising three subway lines, plus the provincially operated GO Transit commuter rail service, which connects the suburban hinterland to the downtown office district. From 1954 to 1980, the TTC built fifty-five kilometres of subways and six dozen stations, which were integrated into an extensive network of buses, trolley buses, and streetcars. The transit system was a great success: in North America, only New York’s and Mexico City’s carried more riders. And then it nearly ground to a halt: over the next thirty years, as the population of Toronto’s metropolitan census area jumped by 40 percent, the city added just thirteen kilometres of subway, fewer than twenty subway stations, and a handful of light rail lines. The sprawling 905 municipalities spent nothing on local rapid transit, until a 2006 agreement to extend an existing TTC subway line into York Region. So while the Ontario government has spent billions to expand capacity on its commuter rail and bus service, the GTA continues to suffer from worsening congestion, grinding commute times, and deteriorating air quality—the consequences of decades of car-oriented planning and lack of investment.

The problems began in 1972, when the Ontario government cancelled the controversial Spadina Expressway, in the face of opposition led by urban activist Jane Jacobs and residents of the neighbourhoods in the proposed highway’s path. It was the right thing to do, but Metro had no viable alternative to the discredited highway strategy. Bill Davis used the occasion to signal the province’s interest in building space-age magnetic levitation transit routes around Toronto, a half-baked idea that went nowhere. Metro soon embarked on a broad planning study, the Metro Toronto Transportation Plan Review, which published its findings in 1975. Eric Miller, director of U of T’s Cities Centre, describes the MTTPR, which recommended a range of subway and light rail projects, as the city’s last serious transportation planning exercise. “It was a very extensive transit plan,” he says, “none of which was built.”

During the 1980s, the Ontario government, still enthralled with the idea of spurring made-in-Ontario transit technology, insisted the TTC buy an untested Bombardier light rail system for one of the few expansion projects completed during the 1980s, the Scarborough RT. Incompatible with the TTC’s subway rail gauge, it turned into a costly white elephant, plagued by technical and service flaws, and is scheduled to be replaced with a conventional LRT system by the end of this decade.

In 1985, ten years after MTTPR, Metro officials released Network 2011, a long-term plan to build three new subways. But in the mid-1990s, after the TTC finally began construction, the Harris government cancelled funding for all but a portion of one of them, the five-station Sheppard “stubway,” as it phased out provincial transit funding altogether. A hard-core fiscal conservative, Harris believed transit costs should be borne by municipalities, although late in his term he reversed himself and launched a multibillion-dollar program to expand the GTA’s commuter rail network.

Following Vancouver’s lead, Dalton McGuinty set up a regional transit agency in 2007 called Metrolinx, which was charged with developing a long-term, integrated transportation strategy for the GTA and neighbouring Hamilton. The agency’s mandate was to take the politics out of transit planning, and transit planners found much to praise in its Big Move strategy, a twenty-five-year, $50-billion initiative that called for more LRT routes, commuter rail, bus rapid transit, and high-occupancy vehicle lanes. But unlike Greater Vancouver’s TransLink, which is funded through fares and a portion of municipal property taxes, as well as provincial fuel and parking taxes, Metrolinx lacked a predictable revenue stream, relying on one-time pledges approved by the provincial cabinet. A decision about a “financial strategy” for the Big Move is expected in 2013, although it is by no means certain that Ontario MPPs will have the courage to implement such unpopular measures as road tolls. Meanwhile, the federal government continues to duck calls for a national program to fund large-scale public transit—a given in virtually every other developed country.

All this toing and froing has injected a high degree of chaos into the city’s transit planning processes, which generate lots of talk but little or no action, leaving transit officials up in the air. In 2007, Mayor Miller launched an ambitious plan to build a city-wide light rail network, with streetcars running in dedicated rights-of-way on seven corridors, to link suburban areas that lacked rapid transit. Some transportation and land use planners questioned the proposed routes. Still, Miller pressed on, arguing that the 120 kilometres of light rail, called Transit City, would bring LRT routes to underserved suburban areas that could never support subways, which cost ten times more than streetcars. He argued that light rail represented a cost-effective alternative to subways, and the provincial and federal governments, evidently persuaded, anted up $17.5 billion in funding. TTC officials promptly embarked on the complex task of obtaining regulatory approvals and placing orders for vehicles.

But, once again, it was not to be. First, the McGuinty government, facing deficit pressures, scaled back the provincial funding. Then, after taking office in December 2010, Mayor Ford cancelled all but one of the proposed lines and demanded that the remaining one—which stretched nineteen kilometres along Eglinton Avenue, a midtown thoroughfare—be buried from end to end, a purely aesthetic decision that will cost billions (Ford doesn’t like streetcars). He has pledged to build a suburban subway with private funds, a plan most experts regard as wildly unrealistic; he is now asking the Ontario government for help. Strangely, the same provincial officials who approved Transit City also approved Ford’s decision to gut it, evidence that Ontario’s efforts to take the politics out of transit planning have evidently failed.

The cumulative effect of three decades of cancelled plans, policy reversals, and funding cuts has been corrosive. Congestion makes driving in the GTA frustrating, while overcrowding makes public transit increasingly unappealing. And the situation will only get worse: the GTA’s population is projected to grow by 50 percent over the next two decades, adding as many as a million more vehicles to already overloaded roads. Experts in urban planning and infrastructure understand that the longer a city and its suburbs delay in addressing these issues, the higher the cost of resolving them. In many forward-looking cities in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, spending on public transit is properly regarded as an investment in urban economic development. But neither the Ontario government nor the municipal councils of the GTA have been prepared to impose congestion charges or other measures that would deliver sustained funding for transit expansion. “If you want better transit, you have to pay for it,” says U of T’s Eric Miller. “Without it, Toronto will go into decline.”

Us and them

For much of the twentieth century, Canadian immigration was driven by economic and political forces, newcomers arriving in waves from the British Isles, southern and eastern Europe, and Asia. But in the late 1980s, during Brian Mulroney’s second term as prime minister, Ottawa sharply increased its targets, aiming for about 250,000 immigrants per year. This, along with Trudeau-era reforms designed to eliminate racial barriers, had a profound impact on Toronto’s social profile. Within a generation, the GTA became the world’s most ethnically diverse urban region, as measured by the proportion of foreign-born residents. Four in ten Canadian immigrants now settle in the GTA, although only half locate within Toronto proper; unlike the suburbs of many large American cities, those of the GTA are as diverse as its core.

“Toronto completely remade itself in population, values, and ways of urban living,” says Ryerson University political scientist Myer Siemiatycki. But recent immigrants have faced greater economic challenges than those who arrived right after World War II. A growing body of evidence shows that the immigrant neighbourhoods in Toronto’s older suburbs are experiencing troubling increases in concentrated poverty. In a 2010 study on income polarization entitled The Three Cities within Toronto, U of T geographer J. David Hulchanski reported that since the early 1970s Toronto has seen a precipitous decline in middle-income areas, while between 1981 and 2006 the number of low-income neighbourhoods quadrupled, from thirty to 136. This growing polarization “doesn’t augur well for the city,” says Siemiatycki. “If you want to look for symptoms that Toronto has gone off the rails, that’s about as good as you’ll find.”

The forces driving these socio-economic shifts are complicated and not always subject to policy-makers’ control. In the 1950s and 1960s, newcomers to the GTA benefited directly from the postwar manufacturing boom, which brought with it well-paying union jobs, home ownership, and the accumulation of equity. But such jobs became harder to find as the region’s economy shifted away from manufacturing. So while immigrants today are generally better educated than most native-born Canadians, many juggle multiple part-time jobs in low-paying sectors, such as health care, hospitality, and retail, to make ends meet. For increasing numbers of new Canadians, home ownership, a portal into the middle class, has become almost unattainable.

A series of policy miscues has exacerbated the situation. The provincial government hasn’t pushed professional associations to accelerate credential recognition for foreign-trained engineers, health practitioners, and others who hold specialized degrees. The federal government has shortchanged Ontario in resettlement funding, direct-ing proportionally more dollars to Quebec. When in 2006 the two senior levels of government struck a deal to manage immigration more equitably, they agreed to consult Toronto about its needs. But the arrangement was more symbolic than substantive, and the problem persists: while the GTA continues to absorb the lion’s share of Canadian immigrants, it still lacks the resources to accommodate them.

Which brings us to housing. In the 1940s, the federal government used its fiscal clout to finance public housing in Toronto. And during the mid-1970s, an urban-friendly Liberal minority government created a national social housing program, funding 600,000 co-ops and not-for-profit apartment units, about one-quarter of them in Toronto. But in the late 1980s, the Mulroney government, under pressure from private developers, began winding down support for public housing, and Jean Chrétien’s government continued the process as part of its 1995 attack on the federal deficit. The decline in public funding killed development of new not-for-profit housing in Toronto, forcing low-income families to rely on a private housing market that offered just two products: small condo apartments and single-family tract homes. The Harris government made the shortage of affordable housing worse by gutting tenant protection laws and downloading Ontario’s rapidly deteriorating public housing onto municipalities that were in no position to pay for the deferred maintenance. Not surprisingly, Mayor Ford is now pushing to sell off hundreds of Toronto Community Housing Corporation properties. Ironically, he has also cancelled plans to redevelop crumbling TCHc complexes, using the market-oriented, self-financing formula promoted by his predecessor.

Toronto’s robust development industry, which has built thousands of condos in the past two decades, has shown little interest in constructing affordable rental housing, and the city’s planners have had little success in persuading them to do so. Consequently, increasing numbers of immigrant families have taken refuge in the city’s 1960s-era slab apartment towers; Toronto contains more suburban high-rises than any other North American city. A 2006 United Way study, Poverty by Postal Code 2: Vertical Poverty, found that 40 percent of the tenants living in these spartan buildings were poor (based on StatsCan income categories), up from 25 percent in 1986, and the number is no doubt higher today. Many of these complexes are languishing in a state of chronic disrepair, often with malfunctioning elevators, security problems, and unreliable heating.

The Three Cities within Toronto contained this dark warning: if current trends continue, by 2025 Toronto’s shrinking middle class will have almost completely decamped to the 905 suburbs and beyond. In this bleak scenario, Canada’s largest city will have morphed into a polarized urban landscape where poor suburbs surround a prosperous downtown and wealthy midtown enclaves. A growing number of global cities have experienced similar patterns. Some, like London and Paris, have experienced rioting in disenfranchised outer neighbourhoods. The same may lie ahead for Toronto.

Stupid growth

In 2005, the Ontario government passed two landmark laws, the Greenbelt Act and the Places to Grow Act, designed to contain sprawl across the GTA. The former established a 720,000-hectare buffer around the region, making it North America’s largest urban greenbelt; the latter created a planning framework meant to encourage GTA municipalities to direct 40 percent of new development into urban areas instead of to farmers’ fields. While large developers threatened legal action, smart-growth advocates praised the laws as visionary, although it will take decades to determine whether they will create a denser metropolitan region—assuming they even survive.

The GTA has experienced four decades of substantial growth during which the 905 municipalities, whose borders extend deep into the farmland around Toronto, have gamely approved low-density, car-centric development that stretches as far as the eye can see. Much of this expansion resembled a Ponzi scheme, as rubber-stamping cookie-cutter subdivisions provided the easiest way for suburban municipalities to increase their revenues without antagonizing developers. Hazel McCallion, the long-serving mayor of Mississauga, just west of Toronto, brags that her municipality never incurred any debt, but that’s partly because, like the rest of the 905 suburbs, it didn’t build rapid transit as a means of encouraging compact development.

Nor did the 905 municipalities demonstrate any interest in getting together with Metro to coordinate the region’s growth. In the absence of a governing body such as the Greater Vancouver Regional District, virtually no connection exists between land use and transportation planning. Case in point: a 2011 study by the Canadian Urban Institute found that while the GTA contains 200 million square feet of office space, making it one of just four such regions in North America, 54 percent of that prime real estate lies far beyond the reach of rapid transit. That’s a huge shift: thirty years ago, almost two-thirds of commercial space was located in the financial district or along subway lines. What’s more, many people who work in these suburban offices own homes in low-density subdivisions, where the absence of public transit forces them to drive wherever they need to go. The net result: Toronto, like many large North American cities, is now ringed by a huge band of intensely car-dependent suburbs.

Pamela Blais, a Toronto-based planning consultant, argues that GTA sprawl is in part an unintended by-product of the Ontario-made regulations governing the fees municipalities collect from developers to help finance growth-related infrastructure. In 1997, the Ontario government passed the first Development Charges Act, whose objective was to make growth pay for itself. But according to Blais, who recently published a book titled Perverse Cities, the regulations fail to adequately distinguish between different types of development. The levy for an infill townhouse in an established neighbourhood is typically the same as one for a new home in a greenfield subdivision, even though the latter will require more costly municipal servicing. Water and sewage mains will have to extend over greater distances, for example, and more pavement will be required for roads. In effect, compact development often subsidizes sprawl.

Many major cities, such as Copenhagen, Paris, and Portland, Oregon, are planning for a low-emission future characterized by higher densities; better and more extensive public transit; additional cycling infrastructure; and financial restrictions on car use, such as parking levies and congestion charges. In comparison, the Ontario government’s initiatives—smart growth laws and the creation of a regional transit agency—seem tentative and unlikely to slow the car-dependent development that threatens the GTA’s economic viability. As Blais says, “It’s time for a big rethink.”

Aging gracelessly

In the past two years, construction cranes have appeared on a long-derelict section of Toronto’s waterfront, ending a twenty-five-year development hiatus that began when the city quietly approved the construction of drab, barricade-like high-rises adjacent to Harbourfront Centre, a culture and tourism complex established by the Trudeau government in the 1970s. The new developments—an office complex, a community college, and a 140,000-square-metre mixed-use project—are surrounded by innovative parks and boardwalks. Nearby, a cluster of 10,000 apartments will be built over the next four years, in preparation for the 2015 Pan Am Games.

Much of this growth is attributable to the efforts of Waterfront Toronto, a development corporation created by the federal, provincial, and municipal governments as part of Toronto’s bid for the 2008 Summer Olympics. Armed with $1.5 billion, the agency has a mandate to urbanize the city’s neglected post-industrial lakefront, which hasn’t functioned as an active port or a transportation hub in decades. Waterfront Toronto officials are now overseeing an 800-hectare redevelopment plan, among the largest of its kind in the world. But Mayor Ford and his city councillor brother, Doug, have threatened to elbow aside the agency, slash its budget, and sell off publicly owned Port Lands real estate to shopping mall developers—moves that would wipe out a decade of urban planning of the kind that created magnificent, wealth-generating waterfronts in cities like Barcelona, Chicago, and Sydney. Instead, the Fords’ plan includes such ill-conceived ideas as a monorail and a giant Ferris wheel.

Unfortunately, Toronto’s history is filled with examples of high-minded plans for open spaces that were crushed by its deep-seated disinclination to invest in the public realm. Olmsted Brothers, the legendary landscape firm that built New York’s Central Park, had a waterfront commission in Toronto a century ago, but industrial interests prevailed and it was abandoned. (Co-founder Frederick Law Olmsted designed the park atop Mount Royal in Montreal and many of the public spaces around Niagara Falls. He also did the grounds for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which laid the foundations for that city’s waterfront revival in the 1990s.)

There are exceptions, of course: Toronto’s iconic new City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square, designed by Finnish architect Viljo Revell; Mies van der Rohe’s TD Centre; Eb Zeidler’s Eaton Centre; and some of the more recent cultural buildings by Frank Gehry, Will Alsop, Daniel Libeskind, Jack Diamond, and Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg Architects. But for the most part, attempts to introduce innovative urban design have met with resistance from residents and municipal officials alike. The city’s most distinctive public spaces—its unique system of river ravines—were preserved almost entirely by accident, spared by flood plain protection rules that prohibited development after Hurricane Hazel swept through the city in 1954, killing eighty-one people and causing $100 million in damage.

“We live in a culture that undervalues the public realm,” says former city councillor Kyle Rae. “It’s a serious emotional gap.” Early in his career, he pushed the city to expropriate and demolish several derelict buildings on Yonge Street to make way for a large public square. Politicians and landowners fought the plan for years, although Rae’s vision prevailed. Today Yonge-Dundas Square, Toronto’s answer to Times Square, attracts masses of visitors and has given the city’s main street renewed verve and energy. What it hasn’t done, sadly, is change bureaucratic and political cultures that allow shabbiness and mediocrity. “Our major problem,” says Rae, “is that we have a culture of ‘no.’”

The Ontario Municipal Board, a century-old quasi-judicial body with the power to overrule municipal planning decisions, often makes matters worse. In Toronto, with its robust real estate market, the OMB has a track record of approving high-density projects with little regard for how they function at street level. Nor does it help that since amalgamation the city has nickel-and-dimed departments with mandates to protect the public realm (parks, urban design, and forestry), sometimes with ironic results. While the city spent years figuring out how to redesign trash cans, thousands of trees planted along sidewalks died from neglect. (The trees are still dying, and the trash cans are already falling apart.) Before amalgamation, tourists invariably complimented Toronto on its cleanliness. Today it’s hard to believe that the city once prided itself on its appearance, because it now seems incapable of keeping its sidewalks free of litter and its parks free of weeds. Rob Ford’s proposed budget cuts will leave Toronto looking even shabbier, while his voluble campaign to eradicate graffiti has only encouraged its youthful practitioners.

Urban planners warn that the abandonment of public spaces can have enormous unintended consequences. Left untended, assets can become liabilities. Think Central Park in the late 1970s, a deteriorating and crime-ridden place New Yorkers tended to avoid. Such not-so-benign neglect, borne of a culture of stinginess, has been a long-standing element of Toronto’s DNA. It recalls that old saying about knowing the cost of everything and the value of nothing.

Last May, Rob Ford persuaded city council to scrap plans to build a pedestrian bridge over the train corridor that separates the downtown King West neighbourhood from Fort York and the condo communities popping up near the city’s lakeshore. Designed as a double helix, the bridge was to be completed for next year’s bicentennial celebration of the War of 1812, Toronto’s founding moment. But during the planning process, its estimated cost rose from $18.4 million to $22.8 million. Municipal projects often exceed their budgets without even causing a political ripple. Yet in this case, Ford and his supporters cried poor and insisted that the bridge shouldn’t be built and that the land at either end should be sold to help defray the city’s indebtedness. The decision came complete with an ironic footnote: the city had already spent $1.3 million planning the doomed structure, money now lost as officials restart the process.

In the grand scheme of things, the cancellation of a pedestrian bridge seems like a minor event, but it reveals much about the Toronto mindset. While the city can always find money to pave roads, it balks at investing in public spaces. In the world’s great cities, residents understand that as well as improving quality of life, a vibrant public realm creates wealth and attracts investment. Yet in Toronto… well, Torontonians complain endlessly about congestion but refuse to give their political leaders the tools to do anything about it. They boast about the city’s ethnic diversity but don’t much mind if immigrants are warehoused in vertical ghettos. They aspire to live in a creative-class city with serious cultural ambitions, but only if they can pay Walmart prices.

Six decades after the beginning of its epochal postwar transformation, it’s fair to say that Toronto has become a very big city, and a somewhat accommodating city, but not a great city—at least not yet. Which is more than a little strange, because the GTA contains an abundance of talent and energy, tremendous wealth, and intimations of a distinctly Canadian cosmopolitanism. What’s lacking is the will to abandon the story Torontonians have always told themselves, which is that they can’t afford the things big cities need and crave, that they mustn’t exercise the political clout that naturally accrues to large urban regions, and that they shouldn’t manage growth in the intelligent way that the twenty-first century requires.

Toronto, in short, remains the sort of place that plans to build bridges, but then can’t bring itself to pay for them.

This appeared in the November 2011 issue.