The sculpture—a large translucent ice block with the words “Team candu” chiselled into it—wasn’t destined to enjoy a long life in the overheated ballroom of Ottawa’s Westin hotel. But for the almost five hundred executives, scientists, and government officials gathered there one evening in February, it was something to talk about as they foraged at the Asian-fusion smorgasbord and waited for Robert Van Adel, president of Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. (aecl), to take the podium. With twenty-seven reactors under construction around the world and more than a hundred others proposed, Van Adel seemed genuinely upbeat about the state of the industry. “We’re ready to lead the nuclear resurgence,” he said. “Not just in this country, but internationally.” And then he thanked the Canadian government for five decades of financial support (amounting to over $20 billion from taxpayers’ pockets).

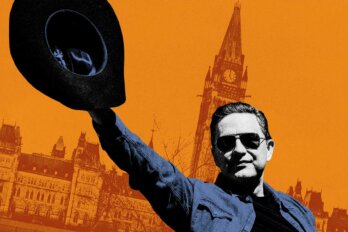

You could forgive Van Adel’s bullishness. After all, the mood at the party hearkened back to the heady days of the 1960s, when science fairs across the country were alive with expositions featuring the Avro Arrow and the candu nuclear reactor, Canada’s homegrown miracle machines. candu skeptics in the ballroom, including environmentalists opposed to nuclear energy and salespeople from rival reactor manufacturers, seemed happy enough to sip their drinks and applaud Van Adel. This was no place to remind him that in recent years the candu has been largely shut out of major markets around the world—and unless Ontario chooses to build the reactor as part of its $40-billion nuclear renaissance, the candu will likely join the Avro Arrow on the expensive scrap heap of Canadian industrial policy.

It’s been more than sixty years since a team of Canadian, American, and British researchers fired up Canada’s first nuclear reactor, the Zero Energy Experimental Pile at Chalk River, Ontario. The zeep was uniquely Canadian. While American reactors run on enriched uranium, which is also used in nuclear weapons, the zeep was powered by natural uranium, which pleased Canadian politicians opposed to the nuclear-arms race. The reactor worked by harnessing atomic fission using a heavier form of water containing deuterium in place of hydrogen. By 1958, engineers with aecl had refined the zeep into a design they dubbed Canada Deuterium Uranium, or candu.

Unlike reactors built elsewhere, most of which copy US models that contain the process within a single high-pressure vessel, the Canadian design features hundreds of pressurized tubes. Although this made the original candus more stress-prone and difficult to maintain, they had one critical advantage over their American rivals: they could be refuelled without being shut down, an attractive cost-saving feature that helped elevate Canada’s peaceful nuclear superiority into nationalist lore in the 1960s and ’70s.

The candus were soon widely considered to be the Porsche of reactors—though not, as it has turned out, the workhorse. By the late 1990s, the candu’s competitive edge had been largely eroded by a dramatic shortening in the time needed to refuel American-designed reactors. This prompted Ron Osborne, former president and chief executive officer of Ontario Power Generation Corp., the provincial utility that currently operates ten reactors, to conclude that the candu could no longer claim an efficiency that offset its complex design. Said Osborne in a blunt critique: “The operating capacities at the very best American plants are superior.”

The reactors were born in an era when Canadian science and technology breakthroughs weren’t unexpected. But unlike the Avro Arrow, which was abandoned by Ottawa, the candu was a political love child never forsaken by its parliamentary parents. Its upbringing was suitably expensive, and the spending has been sustained: in 2004 and 2005, subsidies amounted to $2.4 billion.

Today, thanks largely to former prime minister Jean Chrétien, who was relentless in his support, aecl is one of the largest reactor manufacturers in the world. Twenty-two candus have been constructed in Canada and eleven have been built abroad. The Canadian reactors generate an estimated $2.7 billion worth of electricity annually and support 30,000 jobs. “Chrétien really loved the candu,” recalls Osborne. “There was something personal about it for him.”

But on the international stage Canadian nuclear technology developed a dubious reputation: the candu, as it turned out, seemed to be the choice of dictatorial regimes and was shunned by most democracies. Authoritarian rulers in countries like South Korea and Romania were slavishly courted and the standards surrounding reactor sales were relaxed. To sell two candus to China in 1996, Chrétien dipped into the Canada Account—a fund used at the discretion of Cabinet—in order to lend $1.5 billion, on never-disclosed terms, to that burgeoning state. With Chrétien backstopping the sales, aecl had little trouble outbidding American and European competitors. And when the Sierra Club of Canada filed a federal court challenge claiming that the use of public money automatically required the Chinese reactors to be assessed under Canadian environmental law, the federal government forced them into a six-year war of legal attrition while construction was completed.

Earlier sales of the technology to Pakistan and India in the 1960s raised more troubling questions after both countries built nuclear weapons. Canada suspended nuclear trade with India after it used Canadian technology to develop a bomb in the 1970s. These sanctions remained in place until last summer, when then—Prime Minister Paul Martin quietly agreed to renew relations with India despite its refusal to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. As always, aecl seems to have got its way with the government. “I think they finally decided that for good and sufficient self-interest we should do this,” said Reid Morden, a former aecl president.

While Ottawa continues to push the sale of candus to old customers like Romania, it is being shut out of major markets just as the industry is expanding internationally. In fact, at the risk of wrecking his own party, Van Adel might have described the past year as the candu’s very own annus horribilis. It began when Dominion Resources, one of the largest US utility companies, abandoned interest in using candu technology. aecl had been counting on Dominion to license its product for sale in the United States, where the Bush administration is channelling $12 billion (US) into the construction of new reactors.

Losing access to the US market was a major blow, but things took a turn for the worse when officials in China, where the two Canadian-financed candus recently went into service, said current plans require simpler US-style reactors to be built in the future. The Chinese decision followed one made by South Korea, which had bought four candus in the 1980s and ’90s before it also decided to go with American reactors. With the doors slammed shut in most of the world’s markets, aecl officials are now fighting to hold on to Ontario, where more than half of the province’s electricity is produced by sixteen aging candus. Their struggle began in earnest in June when, despite skyrocketing uranium prices, the Ontario government announced that it would spend $40 billion over the next twenty years repairing the province’s reactors and building two new ones—but not necessarily candus.

Still, Ontario’s decision must have delighted aecl’s chief operating officer, Ken Petrunik, the country’s top nuclear salesman. After decades selling candus to Romania, Argentina, and China, Petrunik is now working on the Ontario project. Speaking to financial analysts in Toronto in April, he insisted that the candu was the “best-performing nuclear product in the world,” then argued that Ontario and the candu enjoy a special relationship. “aecl is vital to the economy of Ontario,” Petrunik said. “If we build in Ontario and continue to be successful, that will create exports.”

But selling more candus to Ontario, where the province’s experience with the reactors has been financially traumatic, will not be easy. By the time they were completed in 1993, the four reactors built at Darlington, east of Toronto, had jumped in cost from a projected $2.5 billion to $14.4 billion. While some of the cost overruns could be blamed on political interference, the candus were also plagued by severe technical problems largely related to their complex pressure systems, which were wearing out far earlier than expected. It was a widespread problem and of the twenty reactors built in Ontario, eight were shut down after less than twenty-five years in operation. Billions of dollars have been spent refurbishing four of the reactors, which are now back in operation. The remaining four have been out of commission for more than seven years, and two of them (at the Pickering station) will never operate again.

Partly as a result of the reactors’ poor performance record, in 1998 the government dismantled Ontario Hydro, the utility that originally purchased and operated the reactors. Amid bitter opposition, the company parcelled out its $38-billion debt (about half incurred by candus) to consumers. Then, in 2001, the province leased the Bruce nuclear generating station on Lake Huron, Ontario’s largest nuclear facility, to Bruce Power, a consortium of companies led by British Energy. As four of the eight candu reactors at Bruce had been shut down, a move to private ownership was deemed necessary. British Energy sent Duncan Hawthorne, a charismatic Scotsman, to bring the plant back to life.

Hawthorne’s arrival signalled the end of the original compact that gave aecl its historic monopoly in Ontario. For decades, aecl executives had been able to count on privileged access to provincial energy mandarins, many of whom fully subscribed to what William Farlinger, the Ontario Hydro chairman who dismantled the company, scathingly described as the “nuclear cult” surrounding the candu.

By handing over the Bruce reactors to a private operator, the Ontario government set the stage to extend private ownership across the provincial nuclear industry. Under Hawthorne’s leadership, the Bruce operations surged back to life, and Hawthorne now says he’s ready to raise private funds to build new reactors. He is looking hard at French and American alternatives to the candu, and when asked how many of Ontario’s new reactors he can build, Hawthorne replied: “Why shouldn’t we build them all”

Ontario politicians have been advised to force the candu to compete with its international rivals. In 2003, a panel headed by former deputy prime minister John Manley, told the McGuinty government that economic nationalism should not be a factor when it comes to deciding which reactors to build. “Ontario should not be biased towards choosing Canadian-developed technology,” stated the panel in its report, “but should seek out the best available technology worldwide.”

Dwight Duncan, Ontario’s Minister of Energy, appears to be listening. Despite intense lobbying from aecl and its partners, Duncan said the province would pursue the best technology at the best price. He has had informal talks with US heavyweights General Electric and Westinghouse Electric, and with Areva, the French-owned nuclear manufacturer. “It is our preference,” said Duncan, “to use Canadian companies and technology, but our first responsibility is to the people of Ontario.”

To overcome Duncan’s concerns about price overruns, aecl has agreed to guarantee the cost of the construction of new reactors in Ontario. It used the same strategy last year to win a $900-million contract to overhaul New Brunswick’s twenty-three-year-old Point Lepreau reactor, though critics claim that such guarantees are hollow because they simply shift responsibility for cost overruns from provincial to federal taxpayers.

What Hawthorne and Duncan ultimately decide is turning into a $40-billion question for aecl. Their dilemma comes down to whether to support hundreds of Canadian communities and companies by buying homegrown reactors or to go with the technology favoured by the rest of the world. “We don’t want to export the jobs,” said Hawthorne. But in the end, he says, his decision will be based on commercial, not political, considerations.

So who does make the best reactors in the world For an answer to that question, people in the industry often turn to Richard Knox, a nuclear specialist based in Cornwall, England. Knox once edited Nuclear Engineering International, a magazine full of loving photos of nuclear power stations alongside articles chronicling the lives of many of the world’s 441 reactors. In addition to comparing the performance of reactors four times a year, he also analyzes their lifetime records. He has concluded that some candus function well year after year, but in terms of average lifetime performance of all units, Knox’s charts reveal that the Canadian reactors still lag behind those built by Westinghouse and Areva, candu’s fiercest challengers for the Ontario contract. aecl claims that its late-model reactors perform better on average than competing designs, but those calculations carefully omit the Pickering candus and all reactors undergoing refurbishment. For nervous politicians then, basic mathematics would suggest that candus might not be the safest long-term financial bets.

Former prime minister John Diefenbaker faced a similar financial calculation when he pulled the plug on the Avro Arrow after deciding that he could no longer pump tax money into the plane’s development. And having done some secret number crunching of their own, foreign reactor makers sense a similar mood in Ontario and Ottawa—the time may be at hand to kill off their rival. If the competition wins out, a question will remain: should the candu be romanticized like the Avro Arrow as a technological triumph that should never have been abandoned or pilloried as the most expensive mistake in the nation’s history