Christopher Stevenson

Christopher Stevenson

The use of composite drawings based on eyewitness accounts for identifying criminals has its origins in the nineteenth century, but the first commercially available system—one not dependent upon the skills of trained forensic artists—was Identi-Kit, introduced by the Townsend Corporation in the US in 1959.

The original Identi-Kit consisted of a series of transparent cards, or foils, on which different types of facial features and accessories were drawn, arranged in a simple wooden box. To assemble a likeness to descriptions provided by witnesses, a police officer or witness would have a broad variety of eyes, noses, lips, ears, foreheads, jaws, and so forth to mix and match, one on top of the other. After the system was purchased in the late 1960s by the legendary gun manufacturer Smith & Wesson, a new version of Identi-Kit emerged that used photographic foils to render the choice of features more precise and realistic. More recently, mechanical composite drawing kits like Identi-Kit have been replaced by specially designed software.

The version of Identi-Kit used in the current project has photographic foils and was used by the rcmp beginning in 1976. The severe limitations of this method of creating composites for identifying criminals is evident. The forty or so types of each individual feature in the kit have little hope of reflecting the infinite nuances of the human face, and indeed research suggests that Identi-Kit makes it more difficult for witnesses to identify criminals. (Today the rcmp relies on sketches by trained forensic artists.) But when applied to oneself in the form of a self-portrait, it can be revealing of the way a person sees his or her self and appearance.

Twelve Canadians were photographed, asked to construct self-portraits using Identi-Kit, and then interviewed about their experiences of the process and themselves. The result is a study in the complexity and conflictedness of identity, of the subtle disjunctions between how we look from the outside and how we think of ourselves from the inside.

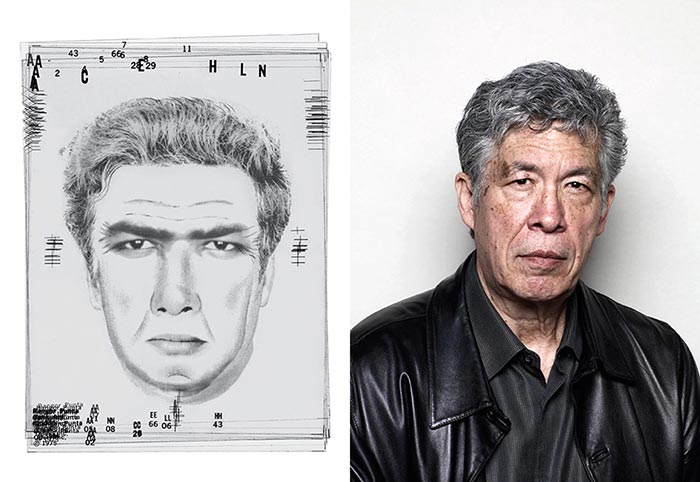

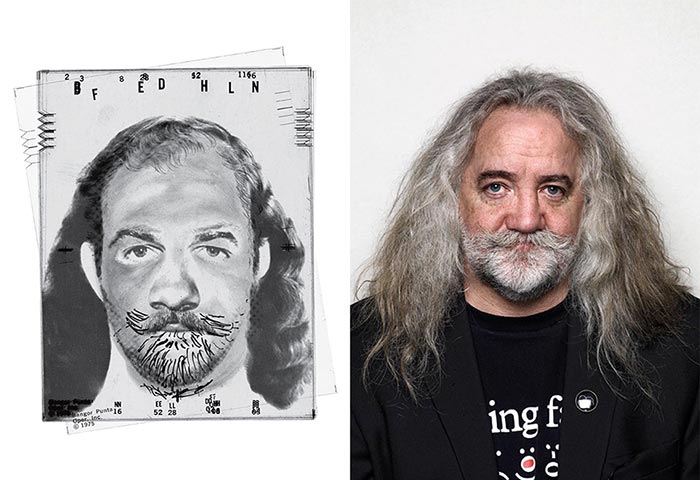

Thomas King, author/politician

I’m like anybody else. I look at myself and I hope I look good. But I think what we do is we look at ourselves, and we try to imagine somebody else that we’ve seen, maybe a movie star or someone else who looks a little bit like us. For whatever reason, the past three or four years, as I’m wandering the streets of Toronto, people want to know if I’m James Coburn. I don’t see the resemblance at all. And James Coburn is dead.

I look more like my father, although I have some of my mother’s features. I thought I had just one brother, and then I discovered, when I was about fifty, that my father had been a busy boy, and that I had seven other half-brothers and half-sisters. We didn’t know about each other. When I was about two years old, my father took off.

My brother looks more like my mother. We say I got the native side of the gene bank and Christopher got the Greek side, because Christopher has hair all over his body and nothing on his head, and I have no hair on my body but I have all of my hair left on my head. He’s younger than I am, so I say that’s the benefit he gets out of this. He could grow a moustache when he was eighteen. I couldn’t grow one until I was forty. I eventually got to the point where I could grow a decent moustache. Then I looked like a Mexican.

About two and a half years ago, I had some real health problems. I was overweight and eating badly. I discovered I had Type 2 diabetes. I didn’t want to go on medication, so I went on a very strict diet and lost sixty pounds over the course of six or seven months. That changed the whole structure of my face and body and put me over into a different age group.

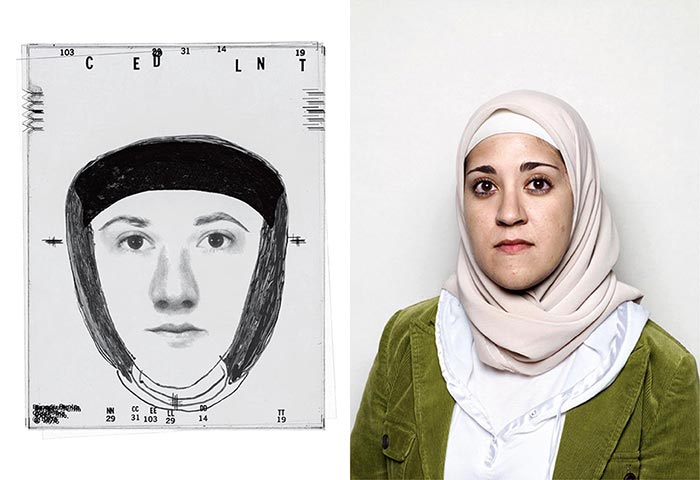

[breakline]Raneem Azzam, Teacher

I started wearing hijab in my second year of university. I was becoming increasingly religious and spiritual. I was around the Muslim association at U of T. I decided I wanted to do it one day. It was sort of gradual, but looking back I might have thought about it a bit more.

I’ve always had a strong sense of identity and sense of self. I’ve never been that concerned about how people perceive me or how people respond to me. When people ask me questions about whether I get negative reactions, I don’t think I do. I don’t think people are really preoccupied with it. At that phase of my life, it was about my own individual spirituality.

Many of my really close friends were wearing hijab just because of the environment at university. My mother doesn’t wear hijab, and I think she was a little uneasy about it at first. I remember one of her friends who was also a professor at U of T said to me, “Why did you do that to yourself? It’ll be so hard to get married now.” There were little things like that, but mostly from the generation older than me, who I guess resisted any kind of pressure to wear it. Not wearing it was a sign of being liberal and modern, and my decision to wear it seemed antithetical to all the things they probably felt were important. But my decision to wear it was as much a statement of independence as their decision not to.

I haven’t considered wearing the niqab. Particularly in North America, it’s such an alienating thing to many people. We identify ourselves by our faces. It would be hard to get people to understand that it’s a symbol of modesty. You wouldn’t have a way of connecting with people if your face was covered.

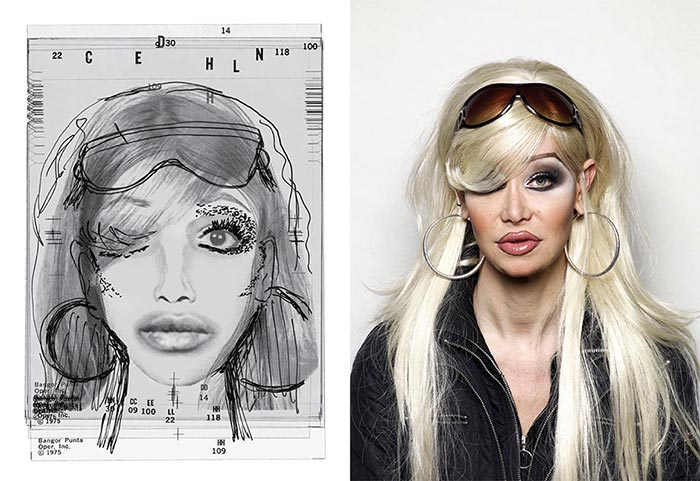

[breakline]Nina Arsenault, entertainer

I’ve had about sixty cosmetic surgeries and procedures, half of them on my face. I’ve had five nose jobs. I had a procedure where they pulled the inside of my mouth to the outside of my face, and that’s actually my lips. I’ve had my eyebrows lifted, my chin refined, my jaw shaved, my ears tucked back.

I’ve spent about $160,000 on cosmetic surgery, or maybe $170,000, I’ve lost track. I was making money in the sex business—I’m a retired call girl now. I used to be a university instructor. My colleagues thought I was crazy to enter the sex business, but I didn’t think I could make the money any other way.

I have found in my experience as an ugly transsexual and as the person I am now—who hopefully is not ugly, who hopefully is pretty—that people are a lot crueller to an ugly transsexual than they are to a beautiful one. When I started my transition, I didn’t look anything like a female. I looked like a guy with a girl’s haircut and plucked eyebrows. When I would walk down Yonge Street, for instance, every single person would look at me, and I would see expressions of pity or revulsion or anger in most of their faces. Now everyone still looks at me, but they have nice expressions on their faces a lot of the time.

I don’t think I had plastic surgery because I am superficial. I spent eight years turning myself physically into the person I wanted to be, shaping my body so people would relate to me in a way I felt comfortable with. I had to get cut open a lot of times, and had to have sex with a lot of men to pay for it. I did that because this is the life I wanted to lead. Now I’m one of the happiest people I know, if not the happiest person I know.

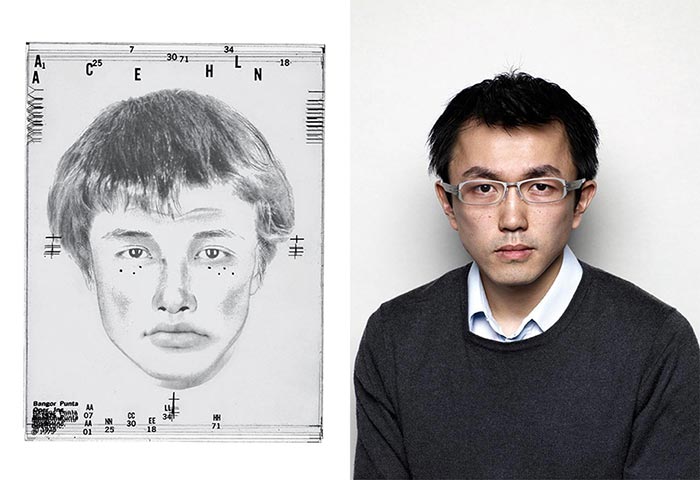

[breakline]Simon Chan, amateur boxer

I know what I look like without having a mirror. I know my hair, the shape of my head, my jawline, the general shape of my face, and all that stuff. I have a pretty strong image of that in my own mind.

Ever since I can remember, I have wanted to box. I’ve been fascinated with the red and blue corners and the red and blue gloves. Still, for me the number one thing is to be safe, just to protect myself. That’s why I have such mixed feelings about the sport. I actually don’t enjoy hurting somebody else. I don’t want to give someone brain damage. That’s something I’ve been struggling with forever.

I’ve really only been punched in the face once, and that was in training. I saw a flash of red. The punch broke my nose. I’ve been healing for a year and a half. Appearance is one thing, but if my nose got broken like it is now and I could still breathe out of it properly, I don’t think I would worry about it too much. But for months after I broke my nose, I couldn’t breathe properly, and I was getting concerned. I considered repair work. If it was something like that—if I had missing teeth and couldn’t chew my food, if I broke my nose and couldn’t breathe, if my nose or face got really disfigured—then I’d consider doing something about it.

Everyone’s face evolves. I’ve got this wicked scar on my nose that I really like. A few years ago, on a trip to Montreal with all my crazy friends, we were at Phillipé’s bar. I remember making a toast with Avery. Our glasses clashed and one broke. A piece of glass cut me right on the nose. Blood was gushing everywhere. So I have a pretty big scar on it. The face shows the war wounds. It shows the mileage. But that’s only on the outside.

[breakline]Michael Williams-Stark, musician/voice actor

At the time of my birth, nobody gave me a trophy, but i was told I was the most severe cleft lip and palate case in British Columbia. I’ve lost count, but I’ve had around thirteen or fourteen surgeries. One can’t be this handsome by nature. It takes a team of surgeons to build a beauty like this.

You learn very early on that the world can be a tough place when you have a facial disfigurement. People would drive by and scream things at me out of cars when I was three or four. I went home and asked my mom how come people were always yelling things at me. I can remember her lifting me up and holding me up to the medicine cabinet mirror and saying, “Well, here’s where you’re different than other people. You were born this way. Here’s what happened.” It didn’t bother me much then. But as I became more of a social creature and went to school, or anytime I’d participate in anything new, there was some hurdle I’d have to jump over. I remember going to buy the latest Beatles album or something, and on my way up to Woodward’s I’d consciously pick the route where I would run into the fewest human beings so I wouldn’t get harassed. To have that kind of stress placed upon those little shoulders is a lot. You become world weary.

Once I taught my first workshop, I just knew. It was like being kissed by God. I got to use all the things I did for a living and combine them with my childhood to come up with this program, Making Faces. I knew right away that improv was a perfect tool, because to get through life you have to make eye contact and use your voice, and that’s very difficult for people with a facial difference.

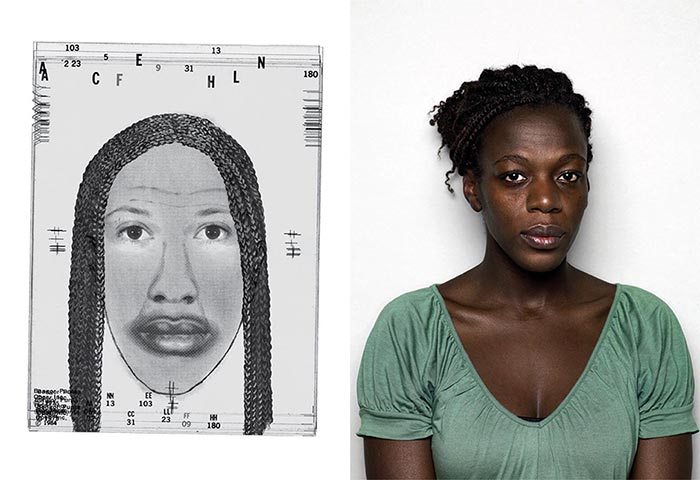

[breakline]Garvia Bailey, radio host

I felt angry with a lot of things, including the kit. Then I started feeling angry with myself—I thought it was me, that I was the problem. I wasn’t thinking about it hard enough or being creative enough or knowing myself well enough to make it work. I soon came to realize it was the limitations of trying to fit myself onto these little cards.

So much of what I am and what I do is about empathizing with people, trying to figure out who they are, trying to get into their heads . This is like therapy—aesthetic therapy—where you have to break yourself down and put yourself back together again. I’ve seen myself through so many other people’s eyes that it’s difficult.

When it came down to it, I had to pick kind, Caucasian eyes. The black eyes were all mean. Not even just the eyes. The lips were mean. The noses—if a nose can be mean. When I put my composite together, sometimes I had to soften it by going to the Caucasian features, which is ludicrous.

For the majority of my upbringing, unless somebody pointed it out, I didn’t see myself as anything different than the little white girls who were all my best friends. I didn’t see myself as different until I moved to Toronto for university, and then all of a sudden I was a black girl. I was supposed to be that, and I didn’t know what that was. For the black kids who grew up in Toronto I wasn’t black enough, and for the white folks I was hanging out with I was a black Toronto girl. It took a while for me to settle into who I am. Being Jamaican and growing up in Stratford has shaped who I am now. It took a lot to reconcile all that and figure it all out and be somewhat comfortable with it.

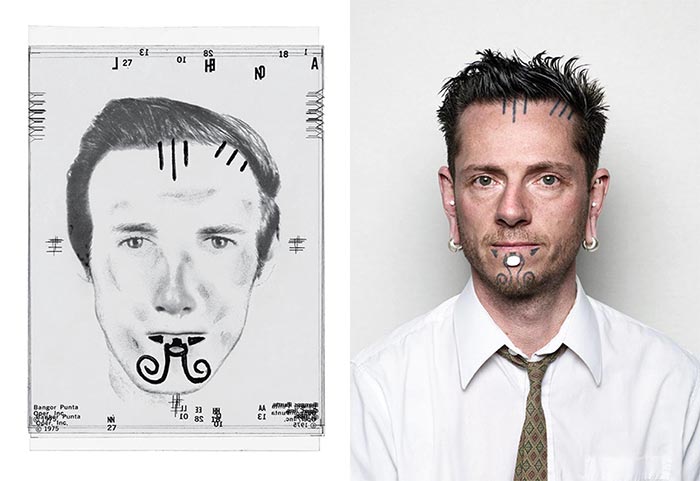

[breakline]Blair McLean, body modification artist

A friend told me to go to this tattoo shop where the guys did really good tattoos. As soon as I went into that shop, I realized that was going to be a big part of my future. Almost instantly, I knew I was going to get my face tattooed.

I was obsessed with the techniques. I started getting more and more tattoos so I could be around that environment. I’ve branded my own arm. I have scarification on my stomach. I’ve tattooed myself. Most of the piercings I did myself. All the stretchings I pretty much did myself. It’s a good way to learn. Thankfully, I researched everything well enough that I never made any mistakes on myself or my clients.

I first got my chin done. Then about four years later I did my forehead. I really wanted something on my forehead. I was lying in bed, and I had this vision of what I felt it should look like. I drew it on and I thought about it, and I thought I love this, this is the one. I’m not going to worry about it after this. Just get this done and it will be perfect.

I keep going back to a vision I had about how I will look when I’m sixty-five. Am I going to be happy with that? Am I going to be happy when the lines start sagging and the colours start fading? I think about that when I get stuff done. There are going to be a bunch of us when we’re sixty-five or seventy sitting around in an old folks’ home with crazy tattoos and ears all stretched out. But we’ll be beside all the people with boob jobs and nose jobs and frozen Botox faces. To each his own.