On December 10, 2008, the federal Liberals reached out to a new leader — a tall, professorial type, a man sometimes criticized as a flaky idealist. Three days later, the Alberta Liberals did exactly the same thing, though with much less fanfare. That the country’s attention was diverted by a constitutional crisis just as Alberta’s Grits were anointing the crusading Dr. David Swann as their new leader seems typical of a party plagued by a certain ill-fated haplessness. Indeed, it may well come as a surprise that there is even such a thing as an Alberta Liberal.

Yet Alberta is a Liberal creation, begun with Prime Minister Laurier’s back-of-a-napkin decision to divide the heart of the North-West Territories into two provinces with a north-south border between them — a border that would in time turn out to have most of the oil and gas on one side. The immigration and land policies that made Alberta a multi-ethnic province of homesteaders, instead of one vast super-pasture controlled by upper-crust Anglos, were Liberal ones. The capital was set up in Edmonton, historically the more Liberal of the big cities, by the Liberals. Many (perhaps a majority) of Alberta’s national treasures, from the storyteller-sage Grant MacEwan to the horticulturist and “Queen of Hugs” Lois Hole, have been Liberals. Alberta has a deep-rooted Liberal self it cannot deny — it just doesn’t vote that way.

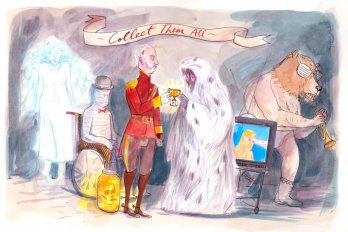

Though it only has 6,200 registered members, the party constitutes an important sociological caste in Alberta. The polite way to define it is that Liberal attachments will be found strong in every profession that makes an occasional practice of opposition to the state; the less polite way would be to say that those who put a high premium on a certain kind of moral image tend Liberal here. Doctors, lawyers, and teachers are overrepresented in the rank. It’s a means of identity-signalling for the stubborn and the righteous, the rationalist and the agnostic, the eco-conscious farmer and the non-profit administrator. Its losing streak now stands at twenty-three consecutive elections.

Swann, whose clear first-ballot victory was announced at Calgary’s Glenmore Inn on December 13, is, for better or worse, the apotheosis of this tradition. (His uncle, orthodontist Gordon Swann, was inducted into the Order of Canada for founding a leading cleft palate clinic, and for his pioneering work in dental forensics.) He has split his professional life between studying and advocating for public health in Alberta and practising gritty front-line medicine in the world’s worst trouble spots. By 2002, as medical officer of health for two regional boards in Alberta’s south, Swann had already attracted notice for his political outspokenness. He crusaded against smoking, he made controversial statements (controversial in Alberta, anyway) about the health risks of pesticides and livestock operations, and he could often be spotted on the street in his spare time protesting US economic sanctions against Iraq.

But in October of that year, when he spoke out in favour of the Kyoto Protocol and talked about its potential to improve air quality and prevent the spread of infectious disease, he really ticked off the wrong people. The board of the Palliser Health Authority, based in Medicine Hat, claimed he had misrepresented the pha’s officially anti-Kyoto views, and fired him from his position as their public health boss. Chastened after widespread public outrage over the firing, the pha attempted to hire him back. After a fit of introspection, Swann rejected the offer, gathered a planeload of medical supplies, and rushed off to Iraq, returning a few weeks later with a prescient warning that the country’s rudimentary medical infrastructure would be helpless to prevent a “holocaust” in the event of a US invasion.

Even as Swann lifted off, a few supporters were writing in to Alberta newspapers, saying they’d rather vote for him than Ralph Klein. In the provincial election of 2004, he ran against a Conservative incumbent in Calgary–Mountain View; Mark Hlady had won the previous election by 3,800 votes, but Swann annihilated him almost two to one. Those who saw him perform at the Glenmore — where, with typical Albertan Liberal luck, the weather was so bitter that the automatic doors of the hotel froze shut — should have no trouble understanding why. With his salt and pepper curls and his towering height, Swann commands immediate attention, even in a filled ballroom. At first, he seemed bemused, almost lugubrious — his wife, Laureen, flitted about, working the room efficiently — but he came to life at the podium, a torpid giant bestirred by some hidden impulse. His deep growl of a voice is so much like Liam Neeson’s that if you close your eyes you might suspect it of being a deliberate impression. “The doctor is in,” Swann boomed Neesonically, and instantly the verdict of the house became unanimous.

But can a man who staked his career on Kyoto, and held an honest-to-God two-week hunger strike for Darfur outside Stephen Harper’s Calgary constituency office as recently as December 2007, push the Grits’ cause forward in oil-dependent, ruthlessly utilitarian Alberta? The Liberal brand still comes with heavy baggage here — the caucus currently comprises just nine members, down from the sixteen elected in 2004 — and there is talk of abandoning it altogether in favour of a merged party, which the new leader has not discouraged. But under any banner, Swann seems more likely to inspire retrospective admiration and fondness than to be trusted with power.