I’d arranged to meet a friend at Big Ben at noon on April 1. But when I arrived, a London bobby patrolling the base of the famous clock tower told me to move on. With the heavily anticipated G-20 Leaders’ Summit set for the next day, the city was teeming with anti-globalization protesters. Vans full of riot police sped through the downtown. “If you see trouble,” he advised sternly, “head the other way.”

I saw trouble soon enough. A police helicopter hovered noisily above as 5,000 protesters surged through the narrow streets of the Square Mile. The demonstrators had smashed the windows of the Royal Bank of Scotland, and they seemed unsettled by the riot squad. Some of them started rocking a police van, prompting the cops to push through the throng of onlookers in a series of flying wedges and cordon off several streets. No one was allowed to leave. When I appealed to one officer, telling him I was a Canadian reporter and didn’t want to get trapped in a riot, he looked at me dubiously and said in a Yorkshire brogue, “That’s what you come to see, in’t?”

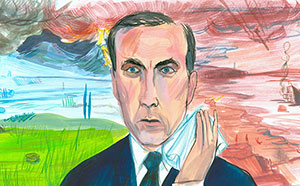

Actually, no. What I’d come to London to assess was the influence of someone who was that same day making a speech about the worldwide economic crisis to an audience in Yellowknife. Though Mark Carney wasn’t in London, his fingerprints were all over the draft G-20 agreement, parts of which had been hammered out at a gathering of finance ministers and central bankers in mid-March.

Speaking in Yellowknife, the forty-four-year-old economist, scarcely a year into the job of running Canada’s central bank, had the summit on his mind as he sketched out how interconnected forces such as the sub-prime mortgage meltdown, massive trade imbalances, and speculation in high-risk financial instruments (“collateralized debt obligations,” “credit default swaps”) had created a cascading credit crunch that was “more than a cyclical shock.” Turning to Canada, he assured the audience that Ottawa’s aggressive fiscal and monetary policies would begin to bear fruit by fall. Despite the fact that he’d driven down the Bank’s key interest rate to an unprecedented 0.5 percent—soon to be 0.25 percent—since last fall’s earthquakes, he hinted he still had other “unconventional” stimulus tools at his disposal, if conditions continued to worsen.

But Carney was also looking past the recovery, to the humbled world emerging from the scariest downturn since the Great Depression. He’d grown convinced that governments needed to expand financial regulation to include hedge funds, private equity, and the other actors in the “shadow banking system.” “This week’s G-20 summit,” he predicted, “should provide the road map for a more stable and effective international financial system.” As one of the mapmakers, Carney already knew that the future wouldn’t look anything like the past.

Going into what British prime minister Gordon Brown touted as the most crucial economic summit since the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which laid the ground rules for the postwar global economy, the world’s attention had been focused on the array of staggeringly large bailout packages—$5 trillion (US) was the number circulating at the summit—approved since the fall. As they arrived in London, the G-20 leaders were intent on preventing a reprise of what had befallen Japan in the 1990s, when a sluggish political response to a similar banking crisis led to a decade of stagnation.

Central bankers like Carney have found themselves in uncharted territory as they scramble to boost the flow of cash through their troubled economies. Starting in early 2008, the world’s major central banks slashed their target overnight rates to counter what they predicted would become a highly contagious credit crisis. A cut in the “overnight” lending rate—the target rate at which big banks, including central banks, make one-day loans to one another—makes it cheaper for companies and consumers to borrow. Even a tiny reduction is “a very big lever,” many times greater than the largest spending project, notes political scientist John Kirton, who runs the G-20 Research Group at the University of Toronto’s Munk Centre.

But by March, many central banks had pushed those rates to almost zero, meaning they’d exhausted one of the primary tools of traditional monetary policy (after all, central banks can’t lend for free, which is what a zero percent rate implies).

Led by US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, central bankers are now resorting to drastic measures. They’ve relaxed their own lending criteria, and are also pursuing “quantitative and credit easing” policies—a form of sanctioned alchemy that allows central banks to inject billions into their economies by acquiring government and corporate bonds, mortgages, consumer debt, and even stocks. The primary purpose of these moves is to avert the hobgoblin of deflation. When consumers expect prices to fall, they delay purchases and can thereby send an economy into the kind of death spiral that turned into the Great Depression.

It’s an unfamiliar role for people in Carney’s position. For the past twenty years, central bankers have increasingly focused on adjusting interest rates to keep inflation in check—a legacy of the stagflation of the ’70s and ’80s, when prices churned upward and borrowing costs followed. Former Fed chairman William McChesney Martin once quipped that the job of the central bank was to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going—but as of 2009, bank officials the world over have found themselves setting out shooters the morning after a drunken debauch.

The G-20 summit began early on April 2, at the cavernous ExCeL convention centre in east London. I rode the Docklands Light Railway past the towers of Canary Wharf to a station near the London City Airport. In a forlorn parking lot, hundreds of journalists were being siphoned through two sets of security checks and cordons, then bused to the venue. After a long night of negotiations and banquets, the American and British delegations were still debating the French and the Germans over the need for more stimulus, as well as the extent of new regulation for the global banking system.

The Brits had prepared a seventy-three-page summary of the crisis. On page thirty-five, in large blue letters, was former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan’s confession that his nearly mystical faith in the free market—exemplified by his decision in the late ’90s not to regulate privately traded derivates—had been misguided. By last year, global speculation in these lucrative, ultra-complex investments had topped $500 trillion (yes, trillion). The implosion of a staggeringly large market that had flooded the world with cheap credit was the defining feature of the economic crisis. As Greenspan conceded to a congressional committee in October, “The whole intellectual edifice… collapsed in the summer [of 2007].”

For years, Greenspan was the embodiment of the all-knowing central banker—a superstar economist noted for his owlish appearance, cryptic public pronouncements, and long friendship with literary libertarian Ayn Rand. His successor, Ben Bernanke, is a bushy academic who came to the job with noted, and evidently fortuitous, expertise in the causes of the Great Depression.

Since the onset of the sub-prime meltdown in the summer of 2007, Bernanke and other central bankers have been under a microscope. When Iceland’s banks disintegrated last fall, the country’s central banker, David Oddsson, became a widely ridiculed figure. Bank heads in the UK and the euro-zone, meanwhile, have faced criticism for failing to check the reckless behaviour of financial institutions, and for responding slowly to calls for interest rate cuts to prevent a recession.

By contrast, the Bank of Canada—which oversees monetary policy, banknote circulation, and Canada’s financial system (though it does not directly regulate the banks)—has sailed through this crisis with its international reputation almost unscathed. More so than in most developed countries, our chartered banks have been diligent about keeping plenty of capital on hand, meaning they could absorb a deluge of defaulting loans without becoming insolvent. Ottawa, meanwhile, owes less money per capita than any other G8 country. Consequently, the Harper government could afford the $40-billion stimulus package introduced in January without subjecting Canadians to a future of lingering deficits. And the Bank of Canada, for its part, hasn’t had to perform financial cpr on the country’s banks.

With 1,400 employees, $79 billion in assets, and a licence to print money, the seventy-five-year-old institution enjoys a reputation for professionalism, conducts extensive economic research, and maintains a wide network of international contacts among other central banking authorities. It is also a bureaucratic Fort Knox in Ottawa, where it occupies an imposing granite and glass complex on Wellington Street. When Carney—whose conservatively groomed good looks and charming manner give him the air of a character out of Mad Men—took over as its eighth governor in February 2008, he arrived as an outsider.

Born in the Northwest Territories, he moved with his family to Edmonton when he was six. He played competitive hockey at Harvard as an undergrad, then did his master’s and doctorate in economics at Oxford. After graduation, he spent thirteen years at the Wall Street investment bank Goldman Sachs, working in several of its global offices, including Tokyo and Toronto. Eventually, he and his young family grew weary of the peripatetic world of investment banking, and he accepted an appointment as a Bank of Canada deputy governor in 2003. A year later, he left his lucrative job for a senior post with the Department of Finance, settling in Ottawa’s upscale Rockcliffe Park neighbourhood.

Carney’s most notable initiative at Finance was to convince his political masters to close a tax loophole that allowed huge companies to boost their profits by converting themselves into tax-free income trusts—a practice that was draining billions from government coffers. Paul Martin’s Liberals, with their extensive Bay Street connections, waffled on the proposal, and Stephen Harper, too, opposed the change. But Carney managed to persuade Conservative finance minister Jim Flaherty of its merits, and when the Tories made their surprise reversal in 2006, senior citizens, a core Tory constituency, were furious about the hit on their portfolios. Coming off the income trust battle, Carney put out the word that he had broader ambitions. In late 2007, the government executed a trade with the Bank of Canada. Longtime Bank insider Tiff Macklem moved to the Department of Finance to become Ottawa’s emissary to the G7 and G-20, while Carney headed to the Bank to succeed David Dodge as governor.

Carney took the job at a time when the political debate over the Bank’s role in the Canadian economy—and its relationship to the government of the day—had been largely settled. But it was not always thus. In the late 1950s, then-governor James Coyne insisted on jacking up interest rates to battle inflation—a controversial move that put him on a collision course with the Diefenbaker government. He resigned in 1961. To preclude future fights, Coyne’s successor, Louis Rasminsky, moved to codify the Bank’s operational independence, laying out a set of rules to mediate major disagreements with Ottawa. During the early 1990s, John Crow, a caustic former International Monetary Fund official, started pushing to rein in inflation. Crow and Paul Martin didn’t get along, and the Liberals, irritated by Crow’s harping, let him walk at the end of his first term, in 1993, and brought in Gordon Thiessen, a Bank insider.

Since that time, the Bank and successive governments have been negotiating “inflation target” agreements (typically in a band around 2 percent) that are periodically renewed. These deals effectively allow the Bank to do whatever it takes to contain inflation, even if that means pushing interest rates to a level that makes it expensive for the government to borrow. The US Fed, by contrast, lacks such institutionalized monetary policy discipline.

After Thiessen retired in 2001, the Liberals appointed David Dodge, Martin’s longtime deputy. Dodge was known as a brilliant, professorial civil servant unafraid to speak truth to power, but his appointment also aligned the ostensibly independent Bank’s goals with those of the Liberal government. Nevertheless, Dodge (who recruited Carney) brought a deep knowledge of the Canadian economy, and he presided over the Bank during a period of unparalleled prosperity. It was toward the close of his term, in the summer of 2007, that the first tremor of the sub-prime meltdown rippled through the economy. The red-hot market for “asset-backed commercial paper”—short-term notes made from bundles of mortgages, car loans, and derivatives—had seized up as investors learned that some of those underlying loans were the tottering sub-prime mortgages that had begun to default in large numbers in the US. Under Dodge, the Bank relaxed its lending criteria, thus injecting liquidity into the banks just as the abcp crisis was threatening to freeze lending.

Carney, who took over from Dodge less than two months after the abcp intervention, is one of the youngest Bank of Canada governors ever, and certainly the only one with such a long stint in investment banking. Economists who’ve dealt with him thus far like what they see. Don Drummond, chief economist at TD Bank Financial Group, describes him as a “good fit.” Some observers note traces of self-importance: “He’s a clever guy, and he wears that on his sleeve,” says former Paul Martin adviser Karl Littler. Both Drummond and Littler note that he’s quite media savvy (although he has resisted requests for one-on-one interviews, including for this article). And nearly everyone I spoke to pointed out that his finance background is vital, because it gives him an insider’s understanding of what’s ailing the markets.

A week before Christmas 2008, Carney was in Toronto to deliver a speech to a group of female investors that he pointedly entitled “From Hindsight to Foresight.” In the US, despite the optimism about Barack Obama’s election and the ensuing parade of awesome bailouts, banks still weren’t lending, and that alarming dynamic was preventing consumer spending and business investment. To keep Canadian banks lending, Carney explained, the Bank had pumped $36 billion of liquidity into the market (the federal government had also bought $75 billion in mortgages). Despite such moves, he had come in for some backbiting in the media for not lowering interest rates more aggressively. “Few forecast these events,” he noted archly, “although, in an outbreak of retrospective foresight, an increasing number now claim they saw it coming.”

Carney had returned a few weeks earlier from a G-20 summit for finance ministers and central bankers in São Paulo. They had agreed to begin figuring out how to improve the oversight of the unregulated corners of the freewheeling global banking industry, as well as “systemically important” financial institutions, such as huge hedge funds and insurance companies. The G-20 leaders subsequently appointed Canada and India to lead a working group that would develop the necessary regulatory reform standards. Tiff Macklem, the Bank of Canada veteran who’d jumped to the Department of Finance, was named co-chair of the diverse group.

As these senior bureaucrats laboured away behind the scenes on a shopping list of dauntingly technical reforms—updating accounting standards, improving bank capital ratios, crafting new disclosure rules for hedge funds and private equity pools—Carney set out to sell a couple of key ideas about how the G-20 could promote financial stability. One had to do with the need for what he called “macroprudential” oversight. Ottawa is awash in financial agencies—the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the Department of Finance, etc.—and the heads of these organizations convene regularly with the Bank of Canada governor to exchange notes. But Carney felt the Bank should play a more assertive role in scanning the economic horizon for puffs of smoke that could turn into forest fires.

To that end, Bank economists have been working on a “financial stress indicator,” a kind of heart monitor that would predict trouble by looking at a range of interconnected statistics, such as rising household debt. Carney also told his Toronto audience that he wanted to see key international institutions take on similar roles, all with an eye to informing policy-makers of brewing trouble. His appealing, if not altogether convincing, belief was that sensible leaders would heed credible warnings. But, he cautioned, “In the rush to respond, we must avoid building the financial equivalent of the Maginot line—over-preparing for a repeat of current events while remaining vulnerable to the root causes of the next crisis.”

The surprising sturdiness of Canada’s banking sector received a great deal of political attention on the road to London. Harper and Finance Minister Jim Flaherty took turns touting the stability of our banks, and in one interview Carney went so far as to characterize the fate of the sector’s hobbled global rivals as a case of “vicious natural selection.” cnn and Newsweek magazine commentator Fareed Zakaria joined in. “Guess which country, alone in the industrialized world, has not faced a single bank failure, calls for bailouts or government intervention in the financial or mortgage sectors,” he wrote. “Yup, it’s Canada. In 2008, the World Economic Forum ranked Canada’s banking system the healthiest in the world. America’s ranked 40th, Britain’s 44th.” It all came down to leverage, Zakaria continued: the Canadian banking sector lent out eighteen dollars for every dollar on deposit. US banks had a vertiginous 26-to-1 ratio, Europe a “frightening” 61-to-1. Suddenly, our banks’ irritating tics—the negligible interest rates on deposits, the outrageous user fees, the institutionalized disinclination to lend—were being recast as signs of national virtue.

There is, of course, a lot more happenstance in the health of Canada’s banking sector than its boosters acknowledged. Queen’s University economist Tom Courchene points out that in the late ’80s, during the run-up to the free trade deal with the US, Canada’s big banks snapped up the country’s large investment houses after Ontario securities regulators threatened to lift ownership restrictions. As a result, the cautious culture of the chartered banks subsumed the freewheeling underwriter-cowboys of Bay Street. In addition, the banks didn’t get too massive to manage, because Ottawa blocked mergers. And their ample capital reserves are partly a legacy of past economic instability, such as the dot-com bust, which prompted them to limit their exposure to risky investments.

But, as Carney noted in a bbc interview, federal regulators also stood up to the big banks when they sought approval to jump into riskier ventures. “They didn’t like that, and they would come in and complain about it regularly, because it was stopping them from doing some of the sexier things that their international competitors were doing,” he said. “But it turns out some of the sexier things that [their competitors] were doing were quite foolish.”

Whatever the cause, Canada’s banks have swanned through the downturn in comparison with their international counterparts, accounting for less than 2 percent of the $923 billion in writedowns suffered by the industry worldwide last year. The big five banks collectively posted $3 billion in profits for the first quarter of 2009 (although several, including rbc, took big hits on their US loan portfolios). As Carney has observed with an air of triumphalism, US and European banks would have to come up with $1.4 trillion in additional capital simply to match Canada’s stubbornly prudent leverage ratios.

It was on these planks that Carney rested his oddly sunny predictions for a robust recovery. In late January, he released a forecast that acknowledged the depth of the recession but predicted 3.8 percent gdp growth for 2010. This ray of official sunshine didn’t jive with mass layoffs in the manufacturing heartland, falling resource prices in the West, and a corporate landscape full of misery. Some critics wondered what the 27 governor was smoking, but University of Toronto economist Peter Dungan didn’t find Carney’s number to be too far off the mark. “Everything is in place for a fairly fast rebound in 2010,” he told me.

Drummond, for his part, was less taken by the specifics of Carney’s prediction than with the public’s reaction to it. He told me that earlier governors, like John Crow, couldn’t communicate clearly with voters, but Carney, for whatever reason, commands attention: “People in the subway were stopping me and asking about the Bank of Canada forecast. It’s amazing—they’re really engaged. What a sea change for this organization.”

With the forecast controversy swirling, Carney and other Bank officials continued to focus on their G-20 plans. In mid-March, two weeks before the London summit, he and Flaherty travelled to the G-20 summit for finance ministers and central bankers, convened at Horsham, a pretty town in West Sussex. The health of the international banking sector—and, in particular, the problem of all those so-called “toxic assets” on the banks’ balance sheets—was at the top of the agenda. Emboldened by the growing reputation of Canada’s financial institutions, Flaherty and Carney had come with the goal of pushing for a more Canadian approach to banking—expanding “the perimeter of regulation,” as Carney likes to say.

The Horsham summit’s final communiqué echoed many of the ideas Carney had been touting all winter, including the need for internationally coordinated oversight and tougher scrutiny for unregulated financial institutions. Describing some of the proposals as “fairly radical,” he told reporters afterwards that he was pleased with the outcome. “One of the things that’s likely to be applied is a belt-and-suspenders approach, or a version of the Canadian leverage test on top of any other capital regime [for] global banks.”

Shortly before 3 p.m. on the afternoon of the London summit, reporters began lining up outside the 800-seat briefing studio in the ExCeL centre, where Gordon Brown would be unveiling the final communiqué. The stage was lined with the flags of the twenty nations, and the graphic behind the lectern showed the summit’s fanciful logo: a graphic of Earth from space, with the sun peeking hopefully over the horizon, directly above Great Britain.

When Brown stepped up to the podium, he boldly declared that the “old Washington Consensus”—which had evolved into a pejorative label for America’s long-standing goal of promoting globalization in trade and investment—”is over.” He then itemized the six pledges agreed to by the leaders. Laying out principles for global banking reform was at the top of his list. The leaders, he continued, had also vowed to establish a “Financial Stability Board” that clearly reflected the Bank of Canada’s vision of macroprudential oversight. (As it happens, David Dodge had already agreed to co-chair a similar organization set up by the global banking industry.) “For the first time, we have a common approach around the world to cleaning up banks’ balance sheets,” Brown said. “I think a new world order is emerging.”

The sexier aspects of the accord garnered the most attention: the vow to crack down on tax havens, something French president Nicolas Sarkozy had been after; the $1.1 trillion (US) in new loan guarantees through the imf, much of which will go toward preventing Eastern European economies from collapsing; and vague promises to bring executive salaries back to earth, a throw to US voters outraged about aig bonuses. But many of the twenty-five recommendations from the Canada-India working group could be found peppered throughout the final communiqué. Canada “co-authored” the report that led to the deal, Harper later boasted.

Some commentators griped about the fact that the Europeans had balked at more stimulus spending. And regarding those regulatory promises, much remained to be worked out. As the New York Times noted, the leaders stopped well short of creating an international enforcement mechanism to rein in rogue lenders or countries that tolerate them. In other words, if the G-20’s newly established Financial Stability Board detects signals of impending disaster, it can do little more than sound an alarm. At least one leader seemed to get that point. “The steps in the communiqué were necessary,” President Obama warned. “Whether they’re sufficient, we’ve got to wait and see.”

The next morning dawned cool and misty, with London’s East End, where I was staying, shrouded in fog. My friend wondered whether the push to establish stricter oversight of the global banking sector meant the end of greed. Of course, the answer was no. Still, there was a sense that an era of turbo-charged financial speculation had limped to a close, paving the way for a safer and duller brand of capitalism—not unlike the sort of thing that passes for a day’s work on Bay Street. As a Guardian column declared, “The masters of the universe have been brought down to earth with a bump.”

As I headed toward the cathedral-like Canary Wharf tube stop in the heart of London’s new financial district, office workers streamed out of the station, their ranks thinned by mass layoffs in the UK banking sector. At the edge of the square outside the station sat the Thomson Reuters tower. An electronic ticker, that flickering symbol of investor frenzy, wrapped around the building’s stone facade. The board showed that most stocks had jumped at news from the summit. It seemed the global market was relieved to have been stripped of some of its freedom.

Bankers’ reputations aren’t built on negotiating super-technical international regulatory accords, of course, and so Carney’s fate for much of this spring has entailed living down that cheerful recovery projection while juggling calls for a more activist approach. Some prominent economists have pressed him to unleash more stimulus. David Dodge, currently the chancellor of Queen’s, even emerged to wag a disapproving finger in his successor’s direction. In an interview with the Globe and Mail, he said that anyone who expected a recovery by fall 2009 “was dreaming in technicolour.”

In late April, after scaling back his earlier growth forecast, Carney unveiled the Bank of Canada’s long-awaited report on its own approach to “quantitative and credit easing,” sending a signal to Canadian markets that the Bank was prepared to get its hands dirty buying up distressed assets.

“It’s the sort of thing that’s been discussed theoretically,” says Nick Rowe, a Carleton University economist and a member of the C. D. Howe Institute Monetary Policy Council. “We don’t have a lot of practical experience.” In the past half-year, Ben Bernanke—a former university professor, remember—has effectively become the largest investor in the history of mankind, approving as much as $7.5 trillion in bailouts, loans, and asset purchases, according to a tabulation by The Atlantic. The Bank of England’s governor, Mervyn King, has also embarked on an easing strategy, with £75 billion in asset purchases. On paper, Carney’s experience in investment banking should prove useful for the easing era in Canada, simply because he presumably understands what kinds of investments aren’t selling on the open market, and why.

He remains patient, for now, in the face of mounting pressure. Well aware of what Bernanke and King are doing with their easing policies, Carney has been content to drop repeated hints (easing if necessary, but not necessarily easing, one might say), the idea being that the Bank might spur economic activity merely by showing an interest in asset purchases. To supplement this strategy, he has promised that interest rates will remain at their historically low level until at least June of 2010, assuming stable inflation. As the spring flowers began to bud, there were scattered signs—stabilizing unemployment and housing sales, stock markets rising, etc.—that the global economy had bottomed out.

Since then, Bank representatives have been hunkered down with other senior government officials, quietly working on implementing many of the reform recommendations approved by the G-20. It’s a sensitive negotiation, and one that could lead to significant changes in the way Canada oversees major financial institutions, non-bank lenders, investment banks, hedge funds, private equity funds, and the provincially regulated securities industry. Government and Bank officials are keenly aware that they shouldn’t be trying to fix what’s not broken. Yet as two of the architects of the G-20 reforms, the Bank and the Department of Finance are also eager to show their stuff to the rest of the world.

While nothing’s official yet, it seems plausible that the Bank will be given responsibility for the macroprudential oversight Carney has been advocating for months. Whether or not it also receives new regulatory powers, this will mark a subtle but important expansion of the Bank’s role, from simply keeping inflation in the 2 percent range to monitoring the overall health of the Canadian economy.

One thing won’t change, however. Carney and other central bankers know they will have to revert to traditional monetary policy in about eighteen months, when the economy begins to heal. That could mean an asset sell-off, and it will almost certainly mean defying public opinion by cranking up interest rates to contain inflation. And like central bankers past, Carney will once again have to climb down from the watchtower and take away that punch bowl.