Books Discussed in This Essay

American Babylon: Notes of a Christian Exile by Richard John Neuhaus

Basic Books (2009), 288 pp.

The Naked Public Square: Religion and Democracy in America by Richard John Neuhaus

Eerdmans (1984), 280 pp.

Can we consider the significance of Christianity to American politics without taking a Canadian delight in deploring American vulgarities? In posing this question, I’m paraphrasing Martin Amis writing about the same challenge from a British perspective. Amis was quoted to that effect by Richard John Neuhaus, one of the most influential Canadian-born intellectuals in American life over the past forty years. During this time, Neuhaus was at the very centre of American history and politics—as an activist, presidential adviser, and man of ideas, but foremost as a man of God. A Lutheran minister and later a Roman Catholic priest, he was comparatively little known in Canada. His Canadian background was an occasionally notable element in his cultural and theological works, and he wrote about Canada explicitly, even polemically, in the journal First Things. Upon his death, in January 2009, obituaries ran in the Ottawa Citizen, which mentioned his nearby birthplace, Pembroke; and in the Globe and Mail and the National Post. The latter also featured columnist Father Raymond de Souza’s moving tribute to Neuhaus as both a mentor and a friend. Meanwhile, in the US, there was nationwide media coverage and letters of tribute and condolence from scores of intellectuals, columnists, and public figures, including then President Bush and Republican leaders in both the Senate and the House.

That Neuhaus was underappreciated in Canada is by no means surprising, given the unapologetically religious cast of his ideas and actions. Contemporary Canadians take little sympathetic interest in the strongly religious dimension of American life. Instead, we tend to be outraged, embarrassed, and often smugly superior over the fact that the world’s most powerful nation seems so permanently in thrall to religion. Never mind that Canada’s own Charter of Rights and Freedoms begins with the declaration “Whereas Canada is founded upon principles that recognize the supremacy of God and the rule of law,” or that every Canadian prime minister since Confederation has been either Catholic or Protestant. What matters is that neither a Canadian leader’s religious affiliation, nor the explicit enshrinement of respect for divine authority in the Charter, exerts much influence on the cultural textures or decision-making realities of our national life.

Early in his last book, the posthumously published American Babylon: Notes of a Christian Exile, Neuhaus sets forth an openly patriotic-sounding expectation of the afterlife: “When I meet God, I expect to meet him as an American.” From a Canadian vantage point, such a statement would seem to represent the way many Americans conceive of the relationship between religion and nation as an uncomplicated interplay of faith and patriotism. But Neuhaus’s mission as a public intellectual was to articulate the complexity of being both a believer and a citizen, without diminishing the significance of either or downplaying the inherent tension of their relationship: “Not most importantly [will I meet God] as an American, to be sure, but as someone who tried to take seriously, and tried to encourage others to take seriously, the story of America within the story of the world. The argument, in short, is that God is not indifferent toward the American experiment, and therefore we who are called to think about God and his ways through time dare not be indifferent to the American experiment.”

Born in Pembroke, Ontario, in 1936, one of eight children, Richard John Neuhaus was by no means indifferent to the American experiment. After dropping out of high school at fifteen, he made his way to Texas, where he worked for a while at a gas station. Eventually, he found his way into a seminary, was ordained a Lutheran minister, and became the pastor of a Brooklyn parish. Moving to New York seems to have provided a suitably intense and sizable arena for his passions and ambitions. He was arrested during a sit-in protest for the integration of public schools at the New York Board of Education, and marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and other clergymen in Selma, Alabama. With the Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Father Daniel Berrigan, he co-founded the anti-war organization Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam; as a Senator Eugene McCarthy delegate, he was also arrested during the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. And with Noam Chomsky, Jane Fonda, and others, he co-signed an anti-war letter published in the New York Review of Books in 1970. At that point, his credentials as a leading left-wing intellectual seemed impeccable. Thirty-five years later, he showed up in the New York Review of Books again, this time as the subject of a conspiracy-minded article by Garry Wills entitled “Fringe Government,” which described him as exerting, from the far religious right, influence in both the Vatican and the Bush White House.

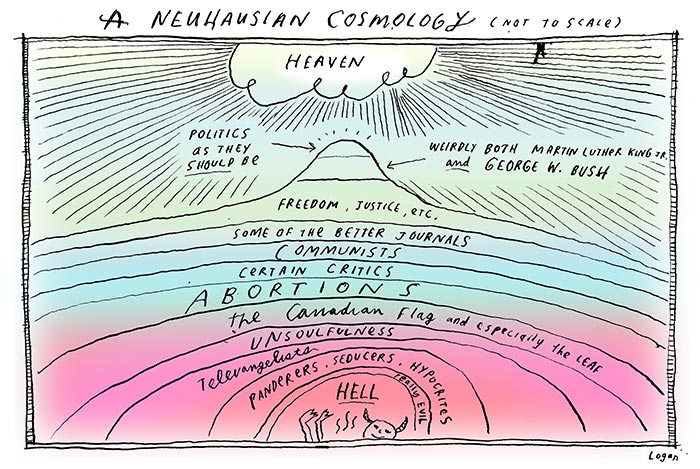

What happened between 1970 and 2005 that so dramatically shifted the ideological space he occupied, if not his personal proximity to history and power? Among other things, a lot of abortions. For Neuhaus, to be against abortion was consistent with being for universal civil rights and against an unjust war. He argued that to be pro-life was to be authentically liberal. A true liberal, after all, is committed, as Neuhaus wrote, to “the protection of the weak and the helpless,” while a conventional conservative would put survival of the fittest and economic efficiency ahead of the rights and value of an unborn child. What may seem now like a rhetorical ploy made sense in the years following the US Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, when the left/right divide on abortion was not nearly as stark as it would later become. Indeed, during the ’70s, as the broader alignments in the culture wars came into focus, Neuhaus found himself differing with his long-time colleagues on the left on matters beyond abortion: US foreign policy, capitalism versus Marxism, sexual morality, racial and gender politics, and the role of religion in public life. His thinking on this last point was a response to an intensification of anti-religious feeling in the halls of American power, and the rise of aggressively Christian efforts to influence American politics.

Feeling little sympathy for either side, Neuhaus wrote The Naked Public Square: Religion and Democracy in America (1984). Invoking de Tocqueville’s pivotal Democracy in America in the title, he framed the book as an intellectual response to the increasing clout of figures like Jerry Falwell and movements like the Moral Majority—then known as “the religious new right.” Throughout the book, he laments their power as dangerous to the integrity and vitality of both state and church. He identifies their appeal as a response to a hyper-secularized view of religion’s relationship to decision making in a modern free state. The questionable achievement of this view, according to Neuhaus, is “the naked public square,” which he describes as a political doctrine and practice “that would exclude religion and religiously grounded values from the conduct of public business.”

One of the dangers of this doctrine, he warned, was nothing less than a right-wing Christian takeover of the state. If the great majority of citizens of traditional Judeo-Christian background—who demographically still represent a great majority of Americans—were alienated from public life because their potential contributions came in part from their religious convictions, these same Americans might eventually find themselves more sympathetically represented by Bible-thumping, anti-intellectual patriots. While elaborating upon this premise by way of a cogent historical and cultural analysis of the American experiment, he advanced his alternative to a public square stripped of or overdressed in religion. His proposal began by recognizing that the problem isn’t the interaction of religion and politics, which he called an “inescapable” fact of the world, “like it or not.” The challenge, he wrote, was to “devise forms for that interaction which can revive rather than destroy the liberal democracy that is required by a society that would be pluralistic and free.”

The most provocative dimension of his proposal for such a revival was his argument that “politics is most importantly a function of culture, and at the heart of culture is religion.” In other words, religion has to be understood as the foundation for a just and free society. Who we are and what we value are questions that transcend national identity and national purpose. Across civilizations and centuries, in churches and synagogues, temples and mosques, the great majority of human beings have expressed their sense of worth and purpose through religion, not secularism, and certainly not politics. Neuhaus argued that for individuals composed into a civic body, for the culture they create and the politics they pursue, religion is the best guarantor of their pre-political dignity. He wanted contemporary American conceptions of justice and liberty to be fully invested in their Judeo-Christian origins, not for the sake of Judeo-Christianity but for the safeguarding and enlivening of justice and liberty themselves.

Six years after the publication of The Naked Public Square, around the same time he converted to Catholicism and became a priest in the New York archdiocese, Neuhaus founded First Things, a monthly journal of religion, culture, and politics. Its contributors, mostly academics, public intellectuals, and the occasional civic figure, draw on religious first principles to inform, sustain, and advance analyses of history, culture, and politics. From 1990 until his death, Neuhaus wrote a column in each issue: searching meditations on religious experience; hard-headed responses to political, ecclesiastical, and cultural developments; as well as analyses of important new books and classics. At his best, he persuasively bridged the divide between civic life and the engaged life of a religious intellectual.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the series of columns he wrote about the sexual abuse scandal that arose in Boston’s Catholic Archdiocese in 2002. At the outset, he stated bluntly that “children have been hurt,” and then emphasized a combination of personal and structural failings as the main source of the harm: “Solemn vows have been betrayed, and a false sense of compassion—joined to a protective clericalism—has apparently permitted some priests to do terrible things again and again.” Later on in the same column, he robustly analyzed the roles of the bishops, the media, and post-’60s American culture in the affair. Throughout his writing on the scandal, he tore apart inquisitional editorials and evasive ecclesiastical press statements; drew on sociological studies of priest abuse and demographic analyses of just how few priests were in fact involved while never downplaying the awfulness of their acts; and always emphasized fidelity to holy offices and to the teachings of the Church—as opposed to stopgap bureaucratic measures, radical reform, or outside legislation—as the strongest possible safeguard against such things happening again.

Now and then, Canada figured in his columns as well. In a 1994 reflection on his father’s life as a minister in 1940s Ontario, he described the national flag as “a red maple contrivance that has all the gravitas of a supermarket logo.” In 2007, he wrote a more serious piece on religion’s waning importance in Canadian life entitled “Europe to the North of Us.” Part autobiography, part historical analysis and cultural critique, it revealed both his critical reaction to Canada’s too-assured rejection of a public role for religion, and how fully American, and fully conservative, by now he conceived himself to be. Still, beyond his predominantly American concerns, he was foremost a Roman Catholic priest. He served in a largely poor parish in New York until his death, and, in addition to his voluminous cultural commentary, he wrote books like Death on a Friday Afternoon (2000), a nuanced theological reflection on the meaning of the Crucifixion. In it, he notes repeatedly that a great part of his own thinking about God, salvation, and human purpose began at the age of seven, when he heard a dramatic sermon on eternal damnation—in Petawawa, Ontario, of all places.

For all his writings and public interventions, Neuhaus will be most remembered for The Naked Public Square. Twenty-five years after its publication, arguments for and against his conclusion—that what’s needed to revive American public life are the rightly ordered roles of both church and state, correcting each other’s tendencies to exert influence beyond their respective writs—are amply evident in the sharply divided contours of current American politics and culture. He takes up this situation in American Babylon: Notes of a Christian Exile. Though not as substantial as The Naked Public Square, it complements the earlier book’s concerns and approach. Once again, he criticizes the religious right, less for being religious or right wing than for being crude and self-defeating in its efforts to inform politics with Christian principles, which, he contends, has frequently led to “the political corruption of Christian faith and the religious corruption of authentic politics.” He recognizes that his own signal work has influenced these efforts by inspiring conservative Christians in the wrong direction—to demand that American political and cultural life reside in an emphatically sacred public square. He argues instead that “the sacred public square is [only] located in the New Jerusalem,” heaven itself, while “the best that can be done in Babylon is to maintain, usually with great difficulty, a civil public square” where the role of religion is neither rejected on principle nor overwhelming in its own presence.

Making a case for a healthy, thoughtful relationship between religion and public life, he offers commentaries on the writings of America’s founding fathers and Biblical passages, analyses of progressive and conservative political movements, autobiographical observations, and critical readings of various post-Enlightenment thinkers, particularly the late American philosopher Richard Rorty. Indeed, Neuhaus sets his vision of what it means to live meaningfully in the here and now in contradistinction to Rorty’s. Through a detailed commentary on Rorty’s thought, he reveals a witty, sophisticated, absolute emptiness at its core: “Nothing is loved for itself except the self; there is no good beyond the self, never mind a summum bonum. All is instrumental to self-creation.” To Rorty’s call for a self-consciously radical post-religious individualism—which, Neuhaus contends, enjoys great traction among both contemporary secular elites and an increasingly secularized general population—he responds, “A self that has only instrumental relations to other selves would seem, however, to be a pitiably shriveled self.”

Neuhaus’s own sense of self proceeds from a religious account of the human person. Invoking in its subtitle Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, his final book is likewise concerned with the situation of someone who’s intensely conscious of being apart from his society, in this case because he regards himself, first and last, as a Christian. He simultaneously recognizes that he’s a citizen, which carries expectations, challenges, and responsibilities that do not immediately or easily align with his religious identity, nor should they. And so the question is, how does someone live out these distinct but inevitably related identities? This carries even more weight because of the stakes: how we live out the time of our earthly exile matters because of our spiritual responsibility to do right unto others, and because our actions in this mortal life will be judged in eternal life. At the end of the book, Neuhaus draws together our daily duties as citizens and our eternal expectations through an extended treatment of hope—not as a vague political term, but as a theological virtue. For Neuhaus, and countless other Christian thinkers, including Pope Benedict, whose thought he draws on here, to hope is to “live forward in time, radically entrusting ourselves to the Power of the Future who is God, and who holds together past, present, and future in the constancy of his love.” To live otherwise, he believed, is to live in hopelessness, regardless of whether you dress it up with cheap patriotism or all your secular smarts and irony.