On the rooftop patio of an old actors’ hotel on a sleepy Sydney street, Ronnie Burkett is contemplating neck joints. For years, he’s been convinced his are the best in the world, but some rare footage has just surfaced on YouTube, showing an obscure design used in America during the ’40s. “The puppet’s head went side to side,” he says, eyes widening, “and I thought I was going to have an orgasm.” The waters of the harbour a few blocks away shimmer in the midday heat as Burkett pledges to duplicate, if not surpass, this miracle of cranial manipulation. It will have to wait, though, until he returns to his Toronto studio.

In a few hours, Burkett will leave this quiet oasis and walk to work, cutting down to the shore so he has an unobstructed view of the waterfront’s famous white half shells as he approaches them. “It’s one of those pinch-me moments,” he explains. “You go, ‘How did a puppet show from Medicine Hat get to the Sydney Opera House? ’” A moment of pride gives way to gentle self-mockery: “I mean, it’s just a puppet show.”

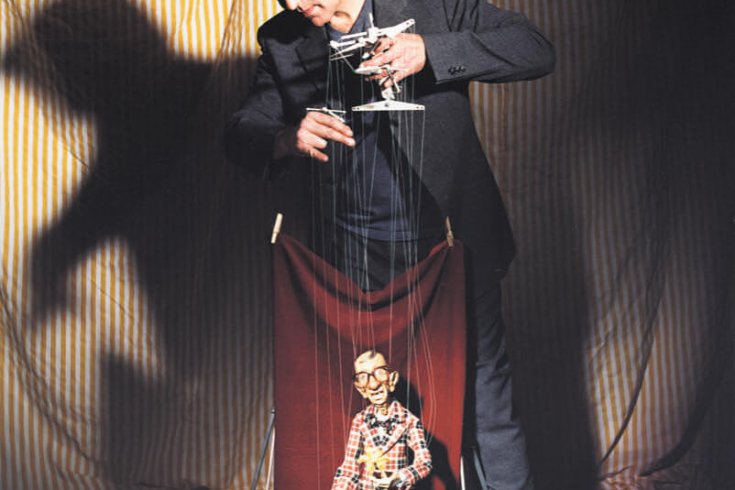

In the pantheon of Canadian pride, the fact that one of the world’s greatest puppeteers hails from a small city in southern Alberta is somewhat akin to our propensity for winning Olympic medals in trampoline: our satisfaction is tempered by doubts about whether anyone else participates past the age of eight. But Burkett’s lack of peers demonstrates that he has essentially invented, or at least reinvented, the genre of serious puppetry. Since he founded the Ronnie Burkett Theatre of Marionettes in 1986, his one-man shows have grappled with kid-unfriendly themes ranging from the Holocaust to AIDS to art history, and over time his puppets have shed their novelty status. To put it simply, his marionettes act. They emote, sometimes holding audiences in thrall while simply standing around onstage and talking to one another, as human actors would.

By the late ’90s, critics were viewing Burkett’s productions as plays rather than puppet shows. “Perhaps the sculpting, manipulation, and stringing of marionettes only need reviewing when they are bad,” Andrew Periale wrote in The Puppetry Journal in 2000. “Thanks to Burkett’s mastery of his craft, and his personal charisma as a performer, it is easy to look beyond these details to the text.” Burkett’s increasing recognition as a playwright has brought him a wider audience of regular theatregoers, many of whom would never otherwise go to a puppet show, and has established him as part of the mainstream theatre community in Canada. Last November, he won the $100,000 Siminovitch Prize in Theatre, which is awarded in turn to a director, a playwright, and a designer over a three-year cycle. Perhaps more telling than his victory, as a designer, is the fact that he is the only person to have been nominated in all three categories.

Burkett’s current production, Billy Twinkle, Requiem for a Golden Boy, which premiered in Edmonton before touring the United Kingdom and Australia, returned in March for shows in Calgary, Montreal, and Toronto. In the show, the title character, a cruise ship puppeteer facing a mid-life crisis after being fired from his job, is compelled by the ghost of his dead mentor to re-enact key scenes from his life—in puppet form, needless to say—in order to remember and rekindle the passion he once felt for his craft. As Burkett puts it, “It’s a show about a puppeteer who’s doing a puppet show about a puppeteer.” The plot offered him a perfect vehicle for such technical wizardry as marionettes manipulating tiny marionettes of their own. But it was also a way of exploring the forces that have shaped his career and his vision for the form’s future. And it provides an excellent entry point for those of us whose prior exposure to grown-up puppetry begins and ends with Kermit the Frog.

The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, recorded the earliest known use of string puppets, in Egyptian fertility rituals honouring Osiris. “The genitals of these figures are made almost as big as the rest of their bodies,” he recounted, “and they are pulled up and down by strings as the women carry them around the villages.” Since then, puppets of various types have been an almost constant presence in cultures around the world, cyclically sustained by two divergent forces: their usefulness as mouthpieces for subversive truths and taboo topics, and the endless fascination they hold for children.

A century ago, puppetry in North America was mostly kid stuff, as it is now. But that changed for a time after Tony Sarg, a Guatemalan-born German who was inspired by marionette shows he’d seen in England, began staging productions in the United States during the ’20s. His performances ushered in what is now thought of as the golden age of American puppetry, placing him at the root of a family tree whose branches aficionados still trace with care. “Sarg begat Bil Baird, who did the Sound of Music puppets and hired me when I was nineteen,” says Burkett.

During the American golden age, countless marionette companies criss-crossed the continent. “My main mentor, Martin Stevens, toured in the ’30s and ’40s with Cleopatra, the Passion play, Joan of Arc,” Burkett says. “Really haunting, naturalistic marionette shows, primarily for adults.” The end of this era coincided with the rise of television, shortly after the Second World War, though television didn’t kill puppetry—quite the opposite. Puppets (and, soon enough, Muppets) were cheap and effective babysitters, and their popularity soared. But they had moved back into the domain of children.

In Billy Twinkle, an aching sense of loss for the bygone glories of the golden age haunts the title character’s mentor, Sid Diamond, a crotchety Shakespearean puppeteer in the mould of Stevens. Other characters bring to life the various trends that have buffeted the world of puppetry over the decades: Billy’s adenoidal rival, Benji, for example, stages puppet shows so avant-garde they no longer feature any puppets. Billy’s cruise ship routine, meanwhile, channels a rich history of racy cabaret marionette acts with a lineage that may well stretch back to Osiris. But at the heart of the drama lies the strained connection between Billy and Sid—not just the conflict between high and low culture, but the endless tension between old and new, and the underlying pursuit of immortality inherent in the mentor-protege relationship.

Burkett’s obsession with puppetry began (his official bio tells us) at age seven, when he flipped open the World Book Encyclopedia and landed on “Puppets.” This glib telling fails to highlight that, for a young boy in Medicine Hat, Alberta, “you couldn’t find a bigger vacuum to have a weirder obsession.” Burkett didn’t see his first live puppet show until years later, by which time he’d obsessively studied every marionette-related book he could get his hands on. In Billy Twinkle, the young boy from Moose Jaw finally gets a chance to meet his peers and heroes when his doting parents put him on a plane, alone, at age twelve, to attend a puppet festival in Detroit. This is not autobiographical, Burkett insists: “I actually went when I was fourteen, and it was in Lansing.” The temptation to view the production as autobiographical is so pervasive that repeated public statements and a disclaimer in the Sydney program have had little effect. “Everyone now thinks I was diddled by a businessman in a motor lodge at age fifteen,” Burkett says with an exasperated smile. “And they go, ‘Oh, poor Ronnie, that explains everything.’ Well, actually, it doesn’t.”

Burkett did, like Billy, use his festival trip to make connections with older puppeteers, who subsequently became mentors. From his home in Medicine Hat, he would exchange long letters with the masters of the golden age, eventually inviting himself to visit during school holidays. There, he would sit and watch and learn. Quietly. “When I used to go to those old boys’ places, I maybe got to sweep the floor and clean out the mould bucket,” he says. In return, he learned about neck joints and other technical arcana, and absorbed the varied experiences and sometimes conflicting approaches of his mentors.

The process of teaching and studying has continued informally throughout Burkett’s career. As we chat on the roof of his hotel, his mobile phone buzzes with a message from a real-life cruise ship puppeteer, still learning his craft, who attended the production the night before. After the show, the puppeteer came backstage with Norman Hetherington, a retired legend whose Mr. Squiggle character was a fixture on Australian TV from 1959 to 1999. The three men talked shop and, as Burkett puts it, “wiggled puppets together.”

Still, at fifty-two, Burkett has yet to replicate the formal apprenticeship patterns of his youth. “Every time someone says to me they want to apprentice, they’re literally saying, ‘Teach me everything about puppetry.’ They have no portfolio; they haven’t read any books.” But the problem extends beyond attitude. Whether because of Muppetization or the disappearance of the small arts grants that allowed him to attend festivals as far afield as Moscow when he was a teenager, there don’t seem to be many young English Canadians exploring the art. Puppetry’s missing generation has made Burkett a master without disciples—or rivals. “I wish there was that new thing nipping at my heels,” he says. “Where is he? Or she? ”

At $100,000, the Elinore and Lou Siminovitch Prize is the largest theatre award in Canada. With that windfall, though, comes an endearing quirk: the winner keeps only three-quarters of it. The other $25,000 goes to a protege of his or her choice. Burkett had received the email congratulating him on his victory just a few hours before meeting me at his Sydney hotel last October, though he wouldn’t be permitted to reveal the win for another three weeks. In hindsight, he was clearly already mulling over the dilemma during our conversation: “I was recently asked who is the hot new thing in puppetry in English Canada,” he said at one point, without divulging who had posed the question. “I can’t give you a name. Quebec has plenty, of course. It supports its own, and the arts scene is alive because of it.”

He eventually found someone: an English Canadian born and raised on Vancouver Island, who discovered puppetry only after moving to Montreal and has been based in Quebec ever since. Clea Minaker was a student at McGill University in 1998 when she saw Burkett’s Tinka’s New Dress. It was the first significant puppet show she’d ever attended, and it changed her life. The relationship between Burkett and his audience was unlike anything she’d experienced in conventional theatre. “I found it absolutely wonderful and fascinating,” she recalls, “that you could be moved to believe in an inanimate object; that collectively we could suspend our disbelief and put life into something.”

She and two friends decided afterward to put on their own puppet show. They borrowed books from the library and wheedled a $1,000 grant out of the university, and seven weeks later put on a forty-five-minute show featuring a mix of string puppets, hand puppets, and other creations. Both of her collaborators from that show are now professional puppeteers, one in New York and the other in Melbourne. Minaker herself is best known for spending parts of 2007 and 2008 on the road with Feist, providing live shadow puppetry and other visuals behind the singer. Perhaps even more impressive to Burkett was the fact that she’d spent three years at France’s national puppetry school before returning to Canada in 2005.

Any mentorship that includes a $25,000 cheque is by most definitions a success. But both Burkett and Minaker hope to make something more of the relationship. The two had met only once before the award, but they’ve since had dinner a few times; Burkett imagines the mentorship will ultimately consist simply of hanging out, loaning her some of the 1,200 puppetry books in his personal library, and exchanging stories. “We have a lot of stuff to share, and I’m really excited to see where her own career takes her,” he said in an email. “She doesn’t do puppetry the way I do, and that’s good.” Already, a chance meeting between Burkett and Atom Egoyan the morning after the Siminovitch ceremony last November has helped facilitate Minaker’s possible involvement in an opera the filmmaker will be directing.

After losing his job in the opening scene of Billy Twinkle, Billy contemplates ending his mid-life crisis by hurling himself over the railing of the cruise ship. Burkett was feeling no such angst when he wrote the play: “All the way up until it premiered in Edmonton, I was adamant that this is not me; this is just a character.” So there was a certain cruel irony to the fact that, a week after the premiere, the federal government terminated the arts export program that helped subsidize shipping costs for Canadian shows touring internationally. Burkett was already committed to runs in Britain and Australia, incurring shipping costs of $21,000 and $24,000, respectively; such expenses are typically borne by the country exporting the show. “Suddenly, within a month, I’m thinking the company has to fold,” he recalls. “So then I did have a crisis.”

Billy Twinkle’s journey back to hope culminates when he meets a junior version of himself, an eager young puppet boy desperate to learn from him. Burkett weathered his real-life crisis by tightening his belt and asking the host countries to help cover shipping. And indeed, after touring the show to enthusiastic reviews and winning the Siminovitch Prize, his confidence is back on the upswing. Still, you can’t help feeling that the final scene of Billy Twinkle is as prophetic as its opening, and that his most redemptive reward was finding the metaphorical equivalent of a twelve-year-old from Medicine Hat—a protege who will join him in carrying forward the endless evolution of their oft-neglected art form.