Early one December morning in 1965, a few months after my arrival in Ghana, I was jolted out of a tropical sleep by a pile of Daily Graphic newspapers whumping onto the concrete floor of my small room.

“What are those for, Atinga? ” I called out groggily to Atinga Naga, the residence cleaner, as he stood at the door, several more such loads balanced in his arms.

“You’ll see!”

And indeed I did. Within minutes came an eruption of shouts, rubber flip-flopped footsteps, and slamming screen doors—unusual noises amid the staid gentlemanliness of Legon Hall, my University of Ghana residence. I leaped up and joined the swarm now flying from bathroom to bathroom, where we found our worst fears realized: the country, in its ninth year of independence, had run out of toilet paper. The new Ghana on which I had staked my future was in crisis.

Not many weeks later, in the dark early morning of February 24, 1966, we heard the sound of distant guns and knew instantly there had been a coup d’état. The campus—and the capital, Accra—erupted as cheering crowds danced in euphoric and spontaneous celebration.

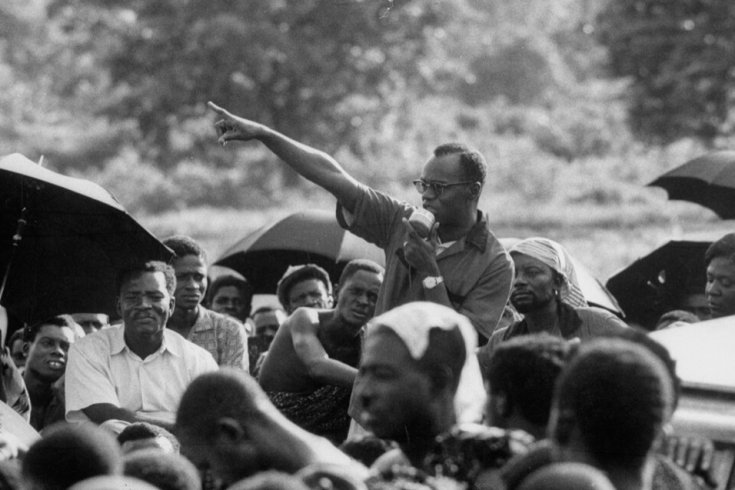

The sudden dearth of toilet paper was far from the only warning sign. Many of my new university friends had claimed for some time that Kwame Nkrumah, the nation’s first president, had lost his way. At the end of October, Nkrumah had hosted a summit of the Organization of African Unity, founded in 1963 in the wake of a continent-wide flood of successful independence movements. He saw the Accra meeting as his chance to win support for his vision of a united Africa, and to show what his brand of socialism had wrought in Ghana’s own eight years of freedom. To him, all Africa was embarked on an irreversible wave toward political and economic independence. And he and Ghana should lead the way.

As it turned out, he was disappointed. Armed with his engaging smile, Nkrumah took centre stage at the oau summit, but soon found that most of the continent’s new leaders shared the British and American suspicion of his obsession with a united continent, and distrusted his motives for and commitment to “scientific socialism.” Only thirteen of thirty-six African heads of state actually came to Accra, and the conference ended with neither continental commitment nor popular enthusiasm at home.

In the Legon Hall residence, the excitement of the event was quickly forgotten. International journalists billeted with us had eaten up our entire year’s allotment of rice and meat. As a result, we suffered an unpopular Yam Festival, consisting of two meals a day of yam: boiled, fried, roasted, and mashed. No rice, no meat. Just yam.

More seriously, disenchanted Legonites accused Nkrumah of fixating on grandiose infrastructure projects: the new seaport and planned city at Tema were a waste of hard-won cocoa earnings; likewise the vast hydroelectric dam, the man-made Volta Lake and its aluminum smelter, the new airport, and the four-lane highway connecting Accra to the port at Tema. Most vociferously, they condemned Job 600, the huge luxury-lodging project designed to impress upon visiting oau leaders the suitability of Accra as the future capital of the United States of Africa.

For a small-town boy from Ontario, this was confusing stuff. I was reminded daily that the African independence wave had moved with proud visibility and relative order to sever the colonial bonds with Britain or France. But I could sense that for new African countries like Ghana there was a hidden cost: Ghanaians, like so many other Africans, were becoming irreconcilably divided between the traditional elites who had expected to take over from the colonialists, and the popular “masses” who had in fact led the struggle, and whom Nkrumah represented. I was surrounded at the university by both the disaffected and the Nkrumah loyalists. Within days of my arrival, three hall mates, suspecting that I might be an American cia plant, had climbed over my balcony, intent on converting me into a solid Nkrumahist.

Their altruism was buttressed by a growing horde of professors from Eastern Europe, Fabian socialists from the London School of Economics, American communists, and hopeful African-American academics, all of whom wanted to help build in now-independent Africa the socialist utopia denied them at home. None of them seemed overly concerned by the increasing security presence, arrests (Ghana had some 1,200 political prisoners in 1965), or disingenuous propaganda issuing forth from the leader’s ubiquitous Convention People’s Party media. To the contrary, Nkrumah’s message sounded to them quite credible: if Ghana and its African neighbours were to be truly independent, they had to outwit the neo-colonialists, control the market, produce centralized five-year economic plans, and borrow however much it took to manufacture anything and everything then being imported from the former colonial powers. If this meant collectivized farming and tight bureaucratic control of prices, wages, imports, foreign travel, and currency—or a few years in James Fort Prison for members of the country’s traditional elite—so be it. The end, the Nkrumahists believed, really did justify the means.

I was all for this, too. Ghana had paid for my Commonwealth Scholarship. Now, here, I had found everything a young man could want: Oxbridge on a tropical hill just beyond Accra; luxurious residence halls, gardens, courtyards, and fountains; an Institute of African Studies with a roster of remarkable international experts; all the Star beer one could drink; good friends; and lively dances under the palms to Ghana’s infectious highlife music. I was impressed, too, with the country’s free health care, and with its free post-secondary education, which my hard-working Ghanaian colleagues seemed to regard as a serious responsibility (not for them the nightclubs of Accra). Though a law school graduate from Toronto, I was no match for their broad classical educations, their debating skills, and the sheer elegance of their written and spoken English.

These Ghanaians were confident, assured, and welcoming. They were in at the start of the new Africa then, and they are very much part of a new Africa now. Today their names are quite recognizable: John Atta Mills, then a field hockey star and law student, now president of Ghana; Nana Akufo-Addo, in 1965 a dedicated Nkrumahist, now the converted free market presidential candidate for the New Patriotic Party; Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, then a high-achieving student, now the internationally respected head of the Electoral Commission of Ghana; Kwesi Botchwey, then an undeniably smart man about campus, now a professor at Tufts, and, until he quit in frustration, the architect of Ghana’s eventual transition to liberal market policies.

They were a seemingly random group at the time, but their lives have come to reflect both the evolution of much of Africa over a half century of independence, and the changing relationship between Africa and Canada. They illustrate, too, what has happened to disappoint and then encourage in Ghana, neatly mirroring the good times and the bad across much of Africa. Their stories have been repeated in Botswana, Sierra Leone, Mali, Tanzania, Senegal, Nigeria. If they have now become the bedrock of Ghana, they are equally a portent of Africa’s future. Encouragingly, their lives prove the exception to the sense of drift and malevolent change that descended on all newly independent African countries in the decades following that initial burst of pride and hope.

The first frenzy of rejoicing at Nkrumah’s demise soon wore off. Ghana’s coffers were bare. Where Nkrumah was said to have wept upon hearing there was no money left to finish the Volta River project, we at the university cried as our hall residence tables were cleared of Milo, Ovaltine, and Maggi sauce. We were being forced to join the masses in losing the small luxuries most Ghanaians now saw as the stuff of life: Norwegian sardines, Argentine corned beef, American Uncle Ben’s rice.

I, too, found the new situation disconcerting. I had lost both the subject of my master’s thesis—the Convention People’s Party—and a good deal of my naïveté. I had come to Ghana expecting to be part of a new vision for an independent Africa. Then, overnight on February 24, 1966, the coup rendered Nkrumah and all that he stood for unmentionable.

I was far from the only Canadian who had arrived hoping to take part in Ghana’s bright future. During my first year there, a friend named John Bentum-Williams, recently returned with a degree from the University of Western Ontario, whisked me away for a holiday in a small northern town. Surrounded by Ghanaian friends and cooled by big, cheap bottles of beer, I thought myself a modern-day explorer. This happy delusion fell apart when I spotted, on the opposite side of the bar, another white face, a woman’s. For most of the night, we managed to avoid each other, but in the end pressure from Ghanaians baffled by such jealousy resulted in an introduction: she was Lynn Taylor and, like me, from London, Ontario. She was in Ghana for two years as part of an enthusiastic contingent of volunteer secondary school teachers fielded by Canadian University Students Overseas and the World University Service of Canada. Adventurous and committed young people like her were scattered in villages throughout Ghana and, for that matter, all over Africa.

The traffic between Africa and Canada during the 1960s—sponsored by governments, churches, service clubs, and universities—spoke of an infectious desire to be involved in the changes sweeping the continent. And it went both ways. Those bringing the best of African youth to Canada hoped to help train the next presidents, senior civil servants, doctors, lawyers, etymologists, and engineers of post-independence African nations. Some, like John Bentum-Williams, returned home to bolster the leadership pool. As the continent struggled, however, many other African elites began to stay abroad, the start of a problematic but ongoing bonanza for Canada. What persuaded growing numbers to leave their homes, friends, and families? How did Africa get from the heady days of independence to a continent that many in Canada perceive only as a place of despair? In the bad, as eventually in the good, Ghana showed the way.

After the coup, the military government initially set about putting the country on a democratic foundation, promoting the candidacy of Kofi Busia, a diminutive, scholarly sociology professor, representative of the right-of-centre elite, who had fled the country under Nkrumah’s rule. He was elected prime minister, and the Western world rejoiced. Canada quickly invited him to pay a state visit, which he did in November 1970. By this point, I had returned to Canada, and the first task of my first real job in what was then the Department of External Affairs was to hold Busia’s briefcase as he was rushed from Rideau Hall to the Office of the Prime Minister, from parliamentary question period to talks with top Canadian International Development Agency officials about more Canadian aid. Though continued Canadian funding for Ghana was certainly forthcoming, the trip was not entirely successful. Busia and his entourage looked askance at having to brave a cold winter rain to plant a commemorative tree in the gardens of Rideau Hall. They rushed away from Canada early to attend French president Charles de Gaulle’s funeral, as much impressed by the dreariness of Ottawa in November as by the generosity of Canadian hospitality and our support for African development.

Back home in Ghana, Busia didn’t last long. His promises of good government went unfulfilled, the economy continued to decline, and he acquired many of the habits that had been Nkrumah’s undoing. Ghanaians quickly grew disillusioned with his inability to put more money in their pockets, and suspicious of his apparent ties to the United States and Britain. They were incensed when he sharply devalued Ghana’s currency; they were irritated by his flashy motorcades and ostentatious security. For most Ghanaians, life in Busia’s “Western” democracy was no better than it had been during Nkrumah’s socialism.

Like so many other Africans, Ghanaians had become ensnared in the Cold War trap, pulled in opposite directions by the ideological proxy battles being waged across the continent by the Soviet Union and the United States. Newly independent nations like Ghana found themselves playing one side against the other to win more aid; imposing trade and business controls; and silencing opposition instead of developing a capacity for independent policy formulation and effective government. The heroes of freedom struggles across Africa eventually became all too proficient at this game, winning Soviet or Western military support and often-self-serving aid, but sacrificing much of the independence they had fought for. To maintain their hold on power, they exploited the pull of petty local nationalism and maintained an enveloping government media. And so Africa sank into an abyss of inflation, corruption, one-party states, dictatorships, conflict, and coups. When Busia was tossed out in another military putsch, in 1972, it was no surprise to my friends from the University of Ghana—or to me, in my new post as a junior officer with the Canadian High Commission in nearby Lagos, Nigeria.

As always with the military governments that drove out so many of Africa’s early leaders, the new Ghanaian regime only accelerated the state of decline. Much the same had happened in Nigeria. We had arrived in Lagos as a newly minted embassy family in 1971, with the country still reverberating from the bloody civil war that had pitted the central government and much of the country against a doughty but soon all-but-destroyed Biafra (Nigeria’s former Eastern Region). We drove frequently over the next few years from Lagos to Accra, relying on our two small children to win the hearts of the customs and police officers who manned the countless roadblocks and border crossings. Amid near-universal economic collapse, these petty officials were bent mainly on collecting a “dash” from defenceless travellers making their already unpleasant journey from Nigeria through Dahomey (now Benin), across Togo, and into Ghana.

Once in Accra, the financial straits were no less distressing. Looking for a way to take their minds off the seeming dead end of life in Accra, some of my friends from Legon had opened up rudimentary disco bars to replace the traditional under-the-palms clubs of earlier, more prosperous years. But even the most lively music and dancing could not disguise the decline of life in Ghana. The military government was stumbling toward seven years of continued economic strife. Inflation climbed; professionals and students went on strike. Rural Ghanaians in particular grew poorer as the country’s farmers, faced with shortages of fertilizers and pesticides, and forced to sell their crops at well below market value, smuggled their cocoa across the border to Togo and Côte d’Ivoire. Another military leader replaced the old one. As far as my Ghanaian mates were concerned, life in those years was truly a descent into hell. They had been betrayed by greedy politicians, a dissipated civil service, and corrupt business leaders. Post-colonial pride and rhetoric had transmogrified into bitter disillusionment.

My family left nigeria in the midst of this, in 1974, sailing from Lagos via Ghana. We were among a faded, rather colonial group sharing one of the final voyages of the Elder Dempster passenger liner Aureol. It was a sad trip: the days of ship travel were over, and as we called at Tema in Ghana and then at Freetown in Sierra Leone, we were bluntly reminded that we were leaving West Africa in worse trouble than we had found it. Our own high hopes at independence had turned to despair. I was on my way to a legal job in Ottawa, and then, in one of those quirks of the foreign service, to a three-year posting in the Philippines.

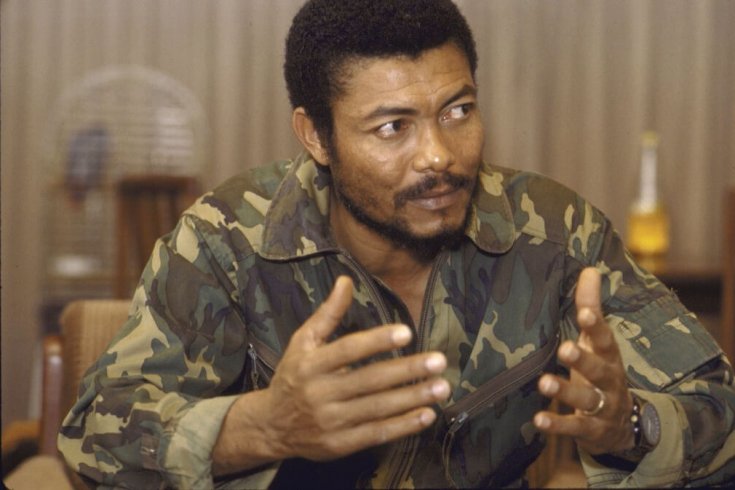

While I was still in the Philippines, in June of 1979, a young, impetuous Ghana Air Force flight lieutenant named Jerry John Rawlings led a coup d’état against his own officers, installing himself as head of a self-styled “revolutionary council.” His first acts were to establish a people’s court, destroy the main market in Accra, order men and women publicly flogged for alleged corruption, and execute the generals who had led Ghana’s earlier, abrupt changes in government. Then, rare among coup leaders, he did as he had promised: in September 1979, he handed the government back to elected politicians.

It took no time for them to outstay their welcome, however, and, frustrated with the newly elected government’s inability to resolve the country’s economic drift, Rawlings pounced again. On the last day of 1981, he staged a comeback. He had lost none of his fervour, praising Castro and Gadhafi, abjuring the West, and denouncing politicians and business leaders alike.

In 1982, I was assigned to the Canadian High Commission in London, once again to be in close contact with African issues, and with many of our friends, now either in self-exile in London, or, like a fortunate few from Nigeria, recently wealthy enough to afford substantial homes in Chelsea or The Bishops Avenue in Hampstead. For the rest at home—both my Legon mates and the working-class Atingas of the country—life during the ’80s was to be at best a challenge, and at worst a constant fight.

Many of my friends were dismayed that their country was once again controlled by an unelected military junta, but they were more optimistic than most Ghanaians, who were fed up with government of any sort. Instead of the proud “Black Star of Africa” Nkrumah had promised, Ghana had descended into a country where nothing worked: health and education had fallen from among the best in Africa at independence to among the most neglected; food supplies were unreliable; and production of cocoa, timber, and gold had fallen disastrously, destroying Ghana’s ability to earn foreign exchange for imports. Rawlings seemed unlikely to provide the leadership Ghana needed. But then, to everyone’s surprise, he did.

During all of Ghana’s strife, donors had not given up on the country. It remained the site of one of Canada’s biggest and longest-standing aid programs in Africa and the Middle East; we worked there hopefully, in tandem with the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US. Still involved, too, were the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Throughout the early years of Rawlings’ rule and into the 1990s, the two global finance institutions attempted to rescue a number of all-but-bankrupt African nations.

To be eligible for this essential financial help, governments had to agree to implement a demanding “structural adjustment program,” which sought to eliminate tariff and exchange controls; cut civil service, health, and education expenditures; and emphasize free market over government-led economic policies. These saps were politically dangerous: they offended notions of African sovereignty, appearing to some to be a new manifestation of Western imperialism; they went against the inclinations of those who had cut their political teeth on socialist economics; they were untried; and, as some prescient leaders and finance ministers noted, they carried with them the risk of social upheaval. But to Western aid experts at the World Bank—and at the Canadian International Development Agency—social and political concerns were less immediate than the need to save Africa from bankruptcy by restraining government spending and opening up markets.

Selling the concept was no easier in Ghana than in most other African countries, in particular because of Rawlings. Like many of Africa’s military leaders and “big men,” he was accustomed to getting his way. Even as a junior officer in the military, he had established himself as a formidable personality. When I first met him, back in the mid-1970s, he was still in the barracks at Burma Camp in Accra. It was fashionable then to be radical, to admire strong socialist leaders, to drink whisky, and to talk tough. Rawlings was frighteningly good at all of these. He prided himself on speaking forcefully and directly, and on taking fast action to right perceived wrongs. Once at the head of Ghana’s government, he paid little attention to most of his ministers, and even less to government bureaucrats. He was also suspicious of his country’s increasingly affluent middle class, which was building huge gated houses on land around the university that had traditionally been the preserve of poor migrants from Ghana’s neglected north. He was more comfortable leading teams to clean out Accra’s gutters than fraternizing with the country’s rising bankers, industrialists, and importers.

Nor was Rawlings given to policy subtleties. His decisions, demands, and actions often appeared bizarre, even embarrassing. At one well-attended commemoration in Black Star Square—speaking before the full diplomatic corps, his ministers, the international media, and a huge crowd of supporters—he called his vice-president a traitor. At a university convocation, after delivering a few appreciative, scripted words thanking the university’s largest private donor, he suddenly turned against the honouree, shouting, “The man’s a crook! Everything he has given the university has come straight from the taxpayers’ pockets!”

Thus, when the World Bank and the imf arrived, preaching structural adjustment, Rawlings was ill disposed toward them. He saw them as an imposition from abroad—one that would weaken his control over patronage and make the economy the fiefdom of Western politicians and businessmen. Only when the economy continued to deteriorate toward complete collapse in 1983 was he persuaded to move, reluctantly, from his populist radicalism to something closer to liberal realism.

Much of the credit for this conversion must go to Rawlings’ reticent finance minister, Kwesi Botchwey. A Legon Hall graduate, once known as much for his charm and love of the good life as for his wisdom, he had matured into a dab hand at economics and political strategy. He, often alone among government ministers, was willing to take Rawlings on, working deftly and against considerable odds to persuade a skeptical president with little background in economics that Ghana had to enter into a devil’s pact with the imf.

Rawlings himself attributes some of his change of heart to Fred Livingston, then the Canadian High Commissioner to Ghana. Like Rawlings, he was an air force man who swore freely and liked to drink Scotch into the wee hours of the night. Back in Ottawa at External Affairs, I was incredulous to hear Livingston’s reports of these late-night chats with the head of a foreign government—yet also unsurprised, after my three years in Manila and four in London, to see what could be accomplished in diplomacy through good personal relationships.

Much later, after I returned to Ghana in August of 1994 as Canada’s High Commissioner, Rawlings confirmed to me that Livingston’s accounts were true. Like many African leaders, he had a soft spot for Canada. He and his ministers attributed to Canadians an integrity, altruism, and commitment that now may seem naive, but which was then not entirely misplaced. Connections and friendships that had grown between leaders of developing countries in the Commonwealth and la Francophonie and Canadian prime ministers—especially Trudeau and Mulroney, and later Chrétien—convinced Africans of Canada’s bona fides.

The feeling was mutual. By 1994, Canada, in concert with other donors and the World Bank, regarded Ghana as an all-too-rare success story. Many African governments had rejected World Bank sap aid and strictures altogether; others had taken them on only half-heartedly. Ghana had not only embraced structural adjustment, it had shown strong evidence of the improvement in economic growth and stability the saps were intended to bring. It had also seen one very large residual benefit: under Rawlings, Ghana grew into a mature democracy—here, too, an example for the continent.

After twelve years of rule, in 1992, Rawlings and his National Democratic Congress had submitted to national elections. These votes, and the ones held four years later, were judged by the donor community to represent the will of the Ghanaian people—a feat duplicated by few other African leaders. Each time, Rawlings and his National Democratic Congress party won, admittedly. But a larger victory was being won by my Legon mate Kwadwo Afari-Gyan and his electoral commission, which ran the votes with an impartiality, a transparency, and a professionalism unknown in much of the rest of Africa. The elections represented a victory for free speech and the media: the Rawlings era had spawned a flourishing opposition press and several private FM radio stations. These provided a constant flow of comment on popular call-in talk shows, ensuring that every step of the election process became instant public knowledge. And, of course, the elections were a triumph for those Ghanaians who had learned to bide their time in parliamentary opposition, confident their turn would come.

Which it did. In 2000, Rawlings stepped down at the end of his second term as elected president, as mandated by Ghana’s constitution. Perhaps he was drawn in by an immensely successful visit in 1998 from US president Bill Clinton; perhaps he was determined to be one of what was then being referred to as Africa’s “new generation” of leaders. But Rawlings did what so few of his counterparts elsewhere in Africa had done: he agreed to leave the fate of the ndc government in the hands of his chosen successor, the highly respected law professor, senior civil servant, and Legon Hall alumnus John Atta Mills.

By a small margin, Mills lost. Rawlings is said to have been deeply unhappy with Mills for conceding, but his successor held firm, and Rawlings was persuaded to accept his party’s move into opposition. John Kufuor and the New Patriotic Party took over. Kufuor won re-election in 2004, but now he, too, is a past president, and his party is once again in opposition. The story of how that happened is perhaps the single most remarkable proof of success in governance on the African continent since the independence wave.

When John Kufuor came to the end of his second constitutional term as president in 2008, he, like Rawlings, stepped aside, making way for yet another Legon Hall alum, his long-time rival and cabinet minister Nana Akufo-Addo. Akufo-Addo lost the 2008 presidential election by less than one percent—a difference of 40,500 votes out of nine million. For several hours, it seemed that Ghana could go the way of Kenya in 2007. Akufo-Addo was under party pressure to refuse to accept the tally, a move that would have inflamed ethnic loyalties.

But it didn’t happen. Akufo-Addo was persuaded by his old Legon mate Afari-Gyan—and, some say, by his countryman and friend, the former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan—to follow his own good inclinations and accept that he had lost. For the second time in a decade, Ghana changed presidents and governing parties with less ado than the United States did when George W. Bush was declared president over Al Gore. And John Atta Mills became president.

Today the maturing democracy in Ghana is the envy of much of the continent. Freedom House, an American think tank, rates it as one of only nine African countries that are truly “free”: twenty-three others, including some with post-colonial histories rather like Ghana’s, such as Nigeria, Tanzania, and Kenya, are only “partly free.” The remaining sixteen are not free at all. Atta Mills, Akufo-Addo, and Afari-Gyan could show them a thing or two about how to run a democracy.

Since i moved on in 1998 from Ghana to Ethiopia, then in 2002 to Zimbabwe, I have dealt with many countries where the prognosis for Africa seems far from hopeful. There is little in Eritrea, Sudan, Angola, or Zimbabwe to suggest that the next decade will be better than the initial post-independence era. But flying into Accra each of these past twelve years—whether from the problems of Addis Ababa and Harare or, more recently, from the satisfied security of Queen’s and Carleton universities in Canada—has always brought me a blood rush of hope, not just for Ghana but for much of the continent.

Last June, I found myself being ushered into Atta Mills’s office, acting for a change not as Canadian High Commissioner seeking out the president, but as one aging university friend seeking out another. There was no Star beer on hand, but there was plenty of reflection. We concluded that we, our other Legon friends, Ghana, and Africa had come a long way over the years.

After our talk, I drove out to Legon Hall to speak with Atinga Naga, the man who had thumped those Daily Graphic newspapers into my room forty-five years ago. He had recently retired. Once a poor man from a northern village, a member of Ghana’s marginalized majority, he had achieved relative prosperity and secured a future for his children in Accra as part owner of a small shop in nearby Achimota, where he owns land and a house. My mates may have built castles in East Legon, but perhaps the best story for Ghana and for Africa belongs to Naga. Fifty years on from Africa’s great wave of independence, his is the dream most Africans still seek for themselves.

This appeared in the July/August 2010 issue.