Mark it down as one of the most remarkable comebacks in Canadian history—maybe the most remarkable. Mark Carney and the Liberal Party have won a government just months after their party faced the prospect of an electoral wipeout. Pierre Poilievre and the Conservative Party will form the official opposition. As of this writing, the Bloc Québecois are on track to be reduced to roughly two dozen seats, the NDP is clinging to its parliamentary life, and the Greens risk a total wipeout.

What the hell happened? It’s a good practice to avoid simple explanations for complex phenomena, but sometimes the story is overly complicated. In Canada’s forty-fifth general election, the primary causes of the Liberal win can be traced to two events without which it’s unlikely the Liberals could have pulled off their Lazarus act: Justin Trudeau left and Donald Trump arrived. One created space; the other filled it with fear.

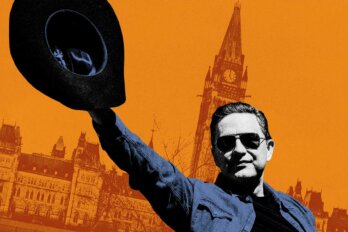

To these causes, we might round out the analysis with a third event: Mark Carney entered the scene. He seemed to fit the moment, as if he’d come right out of central casting. He brought with him a CV—an economist who headed the central bank of two G7 countries—that appealed to a plurality of voters suddenly craving competence. In the churn of economic instability and geopolitical whiplash, people were looking for someone who looked like he knew what he was doing. Carney’s policies got attention, but they played second fiddle. What seemed to matter more was the signal his presence sent: that a “grown-up” was back in charge.

Carney’s win, and it is his win, began long before the writs were issued. In January, the Liberal Party, under Justin Trudeau, was thoroughly cooked and was well on its way to defeat for months. A movement to oust Trudeau had begun earlier, but it wasn’t until Chrystia Freeland, former finance minister and deputy prime minister who was about to be shuffled out of her coveted job, quit the cabinet altogether in mid-December that Trudeau’s fate was sealed. To some Liberal members of Parliament and the public, Freeland’s departure read as another Trudeau shortcoming, revealing an incapacity to manage a key relationship and meet the moment. Thus, history was remade—and in short order.

The day before Trudeau announced his intention to resign, on January 5, the Liberal party was polling at an aggregate 20 percent, a full twenty-five points behind the Conservatives and just one point ahead of the NDP. Immediately after Trudeau’s departure date was set, the Conservatives began to free fall in the polls, while the Liberals rebounded. By the time Carney was chosen as leader on March 9, the race had tightened, with the Liberals closing the gap to six points.

Carney and his team knew how to read the polls and the trends behind them; the Liberals had momentum, and voters were willing to consider giving them another shot if the party could at least seem distinct from the one led by Trudeau. Carney quickly reduced the unpopular carbon tax rate to zero percent, which the Conservatives had opposed and vandalized for years, leading the charge in growing public opposition to it. He pledged to reverse the Trudeau government’s capital gains inclusion rate increase, which sent a further message that he wasn’t Trudeau while supporting the new party line that the prime minister was here to “catalyze private investment” and grow the economy.

He travelled to France and the United Kingdom to send a message to the United States—and Canada—about where the country’s future might rest. The trip was an attempt to make Carney look like he’d accomplished a great deal already in his short time as prime minister—a statesman from day one—and to set up an election that would be contested against Trump as much as Pierre Poilievre. Then, just over a week after he was appointed prime minister, Carney asked the governor general to dissolve Parliament and send the country to the polls. By the time the campaign began on March 24, Abacus Data reported that the Liberals were up eight points. It was hard to believe, but evidence was adding up that the Liberals were as thoroughly back as they’d been thoroughly cooked.

By the time the election began, Trump’s attacks on Canadian sovereignty were well-known, routinely making headlines and enraging most who read about them. The leader of the global hegemon wanted to make Canada the “cherished fifty-first state” and, in the meantime, was undertaking a war by other means, which is to say threatening annexation by “economic force” and slapping punitive tariffs on Canadian industry. Nationalism surged, leading to boycotts of American goods and travel, US hooch being pulled off the shelves of provincial retailers, sports fans booing the Star-Spangled Banner at events, and everyone raising questions about the country’s future: how we’d make our own way in a rapidly changing world, and who would be best suited to the task.

A plurality of voters constrained by an electoral system in which the winner takes all soon decided that the answer was Mark Carney and the Liberals. The new party leader and prime minister was consistently ranked as the preferred candidate to manage Trump, a concern that prevailed as a leading focus throughout the campaign alongside affordability and a desire for change. Midway through the campaign, David Coletto, founder, chair, and CEO of Abacus Data, published data detailing Carney’s “ability to maintain and even grow his personal popularity,” arguing that “the most important figure that explains this election today is Mark Carney’s net favourable rating.” On April 10, Carney’s favourable rating had risen to 48 percent and his unfavourable rating dipped to 28 percent, a shift Coletto called “rare,” given that it’s atypical for an incumbent to become more popular during an election. In contrast, Poilievre was liked by 40 percent of voters but disliked by 45 percent.

But for some, the affection for Carney went further—and deeper. At an April rally in Scarborough, a woman in the crowd yelled “Lead us, big daddy” at the Liberal leader. It’s an anecdote that threatens to overstate the enthusiasm behind Carney—we aren’t talking Carneymania, a surge in affection of the sort Pierre Elliott Trudeau enjoyed in 1968—but it captures a conception of the leader as a parental figure that a subset of voters were looking for. These voters wanted to be, needed to be, led during a time of uncertainty and chaos.

The Liberals performed worse on the affordability and desire for change ballot questions than they did on Trump. This makes sense given that after nearly a decade in power, the party itself, whoever the leader might be, was going to wear a variety of shortcomings and grievances. It didn’t matter. Enough voters were worried about Trump—and the Conservatives winning—to neutralize Tory numbers that were historically strong.

Poilievre managed to rally considerable support for the Conservatives throughout much of the country. But it just wasn’t good enough in the times and the events that shaped them. The Conservatives weren’t helped by the fact that the Poilievre campaign was incapable of sufficiently adjusting to changing circumstances. They had long planned to run against Justin Trudeau and the carbon tax, but by the time the writs were issued, both had become old news. They hadn’t planned to run against Trump, tariffs, and existential threats to Canadian sovereignty amid a rising tide of nationalist fervour, during which a plurality of Canadians became utterly transfixed by a concern for stability and order.

The Liberal win was made possible by swathes of skittish, would-be NDP and Bloc Québécois voters who opted for the Liberals to stop Poilievre and in hopes that Mark Carney could handle the authoritarian American president who posed a potential existential threat to Canada.

Call this election Duverger’s revenge. French political scientist Maurice Duverger proposed a hypothesis in the 1950s that became known as Duverger’s law. He suggested that electoral systems like Canada’s first-past-the-post system would tend toward a two-party system, as major parties sought to capture as much support as possible, crowding out less popular alternatives. In many instances, Canada defied this hypothetical law, but not this time. And luckily for Carney, it didn’t; had he lost, he would have become the shortest-serving prime minister in Canadian history.

Now comes the governing, and that will be the hard part. In the short term, the government may benefit from weakness or uncertainty regarding the future of its political rivals. Whatever happens with the opposition parties, the Liberals are in charge, and the focus will ultimately be on them. The country still faces an affordability crisis, a housing crisis, a climate crisis, and all the economic and security risks and challenges that come with Trump looking to remake the US–Canada relationship and the world. Economist Angella MacEwen warns that Carney’s “polite austerity,” his promise of a balanced budget, is exactly the wrong policy for the moment. “Big Daddy isn’t here to save you,” she writes, “he’s here to save the economic status quo.” And that status quo, she believes, will only further entrench inequality and inequity, exacerbating existing problems and perhaps leading to new ones, too.

The Liberals will remain in government. They will be responsible for government policy and its successes or failures. In the short term, the party and its supporters will take this time to celebrate a remarkable comeback. In the years to come, Prime Minister Carney will likely discover that whatever his competencies may be, he is just as bound by the law of gravity as his predecessor.