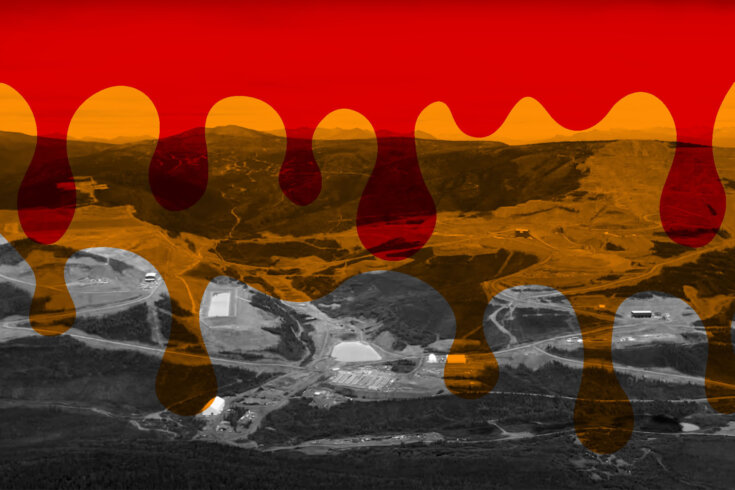

In late June, the heap leach pad at the Eagle gold mine in central Yukon failed. Heap leaching is a method for extracting minerals from ore, and its failure in this case caused a landslide. Cyanide and other contaminants spilled into the valley and entered waterways. Mining halted, hundreds of workers were laid off, and a flurry of water testing began, conducted by the federal and territorial governments and the mine’s operator, Victoria Gold.

The First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun demanded a stop to all mining on its traditional territory. Over the ensuing weeks, while the Yukon government gave regular media briefings on environmental monitoring and containment efforts, the company kept quiet, speaking publicly for the first time only one month after the disaster.

By mid-August, the Yukon government had lost faith in Victoria Gold’s ability to deal with the situation. It successfully applied for a court order to put the company into receivership—meaning a third party would take over the mine, sell assets, and deal with remediation. Victoria Gold’s board resigned promptly, and the receiver, PricewaterhouseCoopers, fired president and CEO John McConnell.

It was a spectacular fall for a company that was once the darling of Yukon mining. Victoria Gold seemed to be sincere about doing things right. The company spent years forming a solid relationship with Na-Cho Nyäk Dun. The two parties signed a cooperation and benefits agreement back in 2011. As part of that, Victoria Gold funded post-secondary scholarships for Na-Cho Nyäk Dun citizens and, by the end of 2023, had provided $6 million to the First Nation for operating on its traditional territory. The company also donated to Yukon groups and events, raised money for programs to boost school attendance, and won regional and national awards for mine development.

Eagle had a wider economic impact on the territory. Air North, the territorial airline, began offering regular flights to Mayo, the community closest to the mine. Work flowed to local businesses and contractors. With about 600 employees overall, Victoria Gold was the Yukon’s largest private-sector employer.

Eagle was especially valued because its success came on the heels of other mine failures. Yukon Zinc, which operated the Wolverine mine in central Yukon, closed in 2015, citing low commodity prices. A couple months later, the company sought creditor protection and restructured, then, in 2019, went into receivership and filed for bankruptcy. The Yukon government is now responsible for reclamation. Last year, Minto Metals abandoned its copper, gold, and silver mine, apparently due to financial troubles. The company stiffed businesses and contractors and left taxpayers to shoulder remediation costs again.

Victoria Gold, by contrast, emphasized its investment in and commitment to the Yukon and its residents. McConnell, who has a background as a mining engineer, seemed hands on and down to earth. I spent a day with him at Eagle back in 2018 while reporting a magazine story, and we ate lunch in the cafeteria. Many mine workers seemed unaware he was the boss.

Things weren’t perfect, though. In 2021, 17,000 litres of cyanide solution spilled from a pipeline at the site. The Yukon government accused the company of failing to comply with water-storage requirements. Victoria Gold pleaded guilty and was charged $95,000. In the summer of 2023, Eagle evacuated twice due to a wildfire. When I interviewed McConnell late last year for a story on the economic impacts of climate change in the North, he dismissed the idea that forest fires were linked to extreme weather patterns.

Nevertheless, Eagle’s largely positive track record contrasted sharply with the events of the summer. Following the slide, the Yukon government expressed frustration, calling it “unhelpful” that the company remained so tight lipped, as reported by the CBC. When McConnell finally spoke to the CBC, he assured that Victoria Gold had no plans to abandon the site, stating, “We’re doing everything humanly possible to prevent this from becoming a major environmental disaster.” The Yukon government saw things differently. After McConnell was fired, his carefully crafted image seemed to collapse as well. He sent out a tone-deaf email: “The past 15 years have been a blast and I’m very proud of what our team accomplished. Stay tuned for my next adventure!”

Mining is tied to the Yukon’s identity. The Yukon became a territory during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. The industry enjoys strong support here, yet there are currently no large-scale operational mines. Eagle’s closure coincides with the Yukon government’s efforts to develop new mineral legislation, expected to be introduced in the coming years. One key issue under review is whether the territory should demand larger securities from operating mines. At present, it reserves a certain amount for closure and remediation. In Eagle’s case, the government has collected about $104 million. But cleanup is likely to cost more.

The full extent of the contamination remains unknown. Also unclear is why Eagle’s heap leach pad—a tested method in mining—failed in the first place. Former workers have alleged unsafe practices, according to the trade journal The Northern Miner, and the Yukon government has said a smaller slide happened back in January. Na-Cho Nyäk Dun wants a public inquiry. The “disaster is a symptom of a larger, systemic, issue plaguing mining regulation in Yukon,” the First Nation wrote in an open letter. “The consequence of regulatory negligence and a business-as-usual approach at an unsafe and unsound site now hangs over taxpayers’ heads.”

In an interview on CBC Radio’s Yukon Morning about a week after the slide, Energy, Mines, and Resources Minister John Streicker—a former federal Green Party candidate—said he thinks people around the world will study the disaster to understand what went wrong. “No one wanted this,” he said. “The mine didn’t, the First Nation didn’t, Yukoners didn’t.”

Correction, October 17, 2024: An earlier version of this article stated that Victoria Gold spent millions on post-secondary scholarships, specifically, and that it won awards for its community work. In fact, the millions were given to the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun as part of the agreement between the mining company and the nation, and Victoria Gold won awards for its mining development. The Walrus regrets the error.

With thanks to the Gordon Foundation for supporting the work of writers from Canada’s North.