F

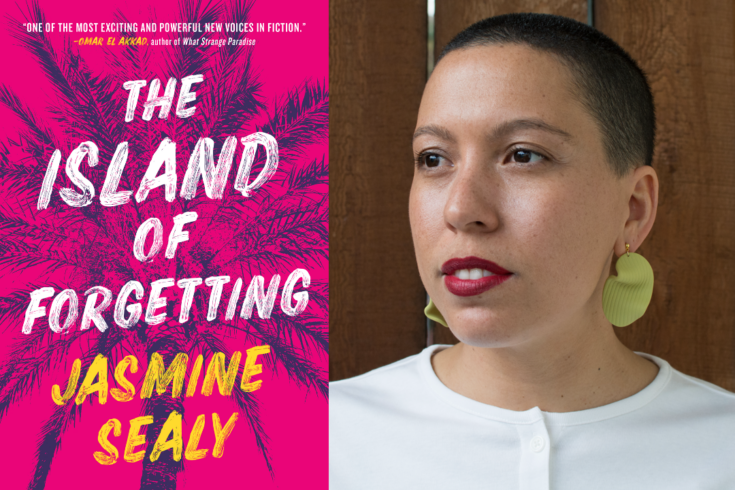

amily secrets never truly stay buried. They show up in our habits, our mannerisms and, sometimes, without any conscious doing, they shape the trajectories of our lives. In The Island of Forgetting, this year’s Amazon First Novel Award winner Jasmine Sealy returns to her Bajan roots in fictional form, unravelling four generations’ worth of fraught family ties through the eyes of ancestors Iapetus, Atlas, Calypso and Nautilus.Linked by the tragedies of their lineage, whether they know it or not, the characters repeat the sins and secrets of their kin. For Sealy, a new mother who only recently lost her father, the prize-winning saga provided an opportunity to unearth the gifts of her own family, pay homage to one of her homelands and make peace as a way of moving forward—even if none of us really ever escape the past.

The Island of Forgetting is a generations-spanning saga about a family that ends up running a beach-front hotel in Barbados. In real life, the island was once a home for you. What about that setting made it a fit for the story, in your mind?

Actually, in some of the earliest drafts, I didn’t specify that it was Barbados. I just referred to it as “the island.” As I got deeper into the writing process, I realized that I was doing that out of fear. Barbadians are a very literary, artistic, academic people. I write for them; I want them to love and to feel acknowledged by this book. Ultimately, I knew that I needed to commit, and that this was a story about a real place and inspired by real people. I needed to trust that I was the right person to tell that story, having not lived there since I was 18. I’m in my 30s now, so I’ve been gone for almost half my life. I had to let a lot of that impostor syndrome go.

There’s an interesting, unsettling tension between the deep, family trauma narrative and the sunny, congenial, surface relationship between tourists and locals. It taps into the (mistaken) assumption that people who work in the tourism industry aren’t people with their own baggage, and who are sometimes seen and written rather one-dimensionally. Does that resonate with you?

One hundred per cent. One of my first jobs was as a server at a hotel restaurant near a cruise-ship terminal in Barbados. I was waiting on tourists. Choosing to set the novel in a hotel was kind of a way of saying: These lives are being lived right under your nose. You don’t need to go into the heart of a country’s poorest areas to see the “real island.” You don’t have to get away from the ‘facade’ of the service industry or get your hands dirty. The real island is the hotel itself—the beach chairs, the drinks that are made, the people serving them to you. They’re real people. You’re just seeing one facet of their lives.

Were there details or curiosities of your own family narrative that you wanted to unravel while writing this book?

Yeah. I remember a conversation that I had with my father before he passed away. He revealed some traumatic things that happened to him in his childhood, and I remember an overwhelming epiphany washing over me. This new information made me completely reimagine my own childhood and the way I experienced being parented by him. I remember thinking: My god. What if I had known this years earlier?

I became super-fascinated by this idea of the unknowability of your parents—the things they choose to tell you and not to tell you, and how the kinds of things they experience shape you. You, as an individual, can also be unknowable to yourself because you don’t know why your parents parented you the way they did. That was definitely the spark that ties the whole book together. The unknowability of the past and, therefore, the present.

We tend to think of generational traumas and gifts as the result of lineage, but for a lot of people, those lines are broken somehow. They don’t actually know what the source of a certain ability or characteristic is, right?

Absolutely. The structure of the book was something that was in place from the very beginning. I knew it was going to be a kind of triptych, completely linear. I wasn’t going to do any sort of braided narrative, where I jumped back and forth from the past. Once you stopped hearing from a narrator, you knew their child was going to be your new one. So, you, as the reader, would have more knowledge of these characters’ lives than they did themselves. When you’re reading Calypso’s section, for example, and she’s talking about her mother, you know the truth about what happened. She doesn’t. And that’s life. You don’t get to go back. You don’t get to hear the other sides of the story.

The novel scaffolds the themes of Greek mythology onto some very human drama—that’s perhaps tame by Olympus’s standards. Why was this a good pairing in your mind?

In the novel, no one dies and there are no epic consequences for people’s actions. It’s all very human. That’s just what appeals to me as a writer. When I read The Odyssey for research, I was interested in the human element: the characters, the personal details. Maybe it’s about empathy—I don’t know. But even when I was in the very brief section where Odysseus is trapped on the island with Calypso, I was like: Why is she doing this? Why is she obsessed with him? What’s going on beneath the surface? There were all of these fascinating potential character dynamics that weren’t explored. That seemed like rich territory to me. Yes, it’s about the battle and the gods and who took whose side. Those are the facts of the story. I see it as a story about when families fall apart.

There’s a ton of complexity in weaving those high- and “low”-level themes together in one creation, so: bravo!

Yeah, there’s a lot going on in there. I just think that there’s something also to be said for having marginalized voices—Black voices, Caribbean voices, women’s voices—in conversation with canonical pieces of literature. That’s something writer Jesmyn Ward said when talking about her novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, which contains a lot of references to The Argonauts. There’s something powerful about linking our stories to these big, epic works.

Do you have a different understanding of your own genetic and emotional inheritances after writing The Island of Forgetting?

Definitely. I became a mother during the process of publishing this book. I gave birth in June and I got the book deal that August. I was making intense changes to the manuscript while recovering from a C-section—in the middle of a pandemic. So this book is deeply intertwined with my own sense of self and motherhood. If there was a big lesson I took away from it—in terms of my own approach to parenting—it would be that there’s something to be said for radical honesty. Especially in Caribbean families, there is a culture of kind of silence, a bit of which is inherited from British colonialism. The stiff upper lip.

I’m very familiar with that.

In the Caribbean, and especially in Barbados, we have it doubly: the intense British heritage and the inherited trauma of colonialism and slavery. The compounded effect of the two means that, well, there’s not a whole lot of unpacking of trauma going on around dinner tables. I can’t speak for all families, but it’s definitely the case for my family. There’s a lot that has gone unnamed. My kid is super young, so we’re not discussing all of this stuff yet, but there’s something empowering about being honest. I think that’s a real way forward to healing.

Have you brought your own child back to Barbados? What was that experience like?

It was amazing. He took to it incredibly. I don’t want to get all mystical, but most 18-month-olds splash around in the water when they go to the beach. He just fit there in a really natural way. My dad was living in the ancestral home my grandfather built, and my son was running around there, barefoot, playing with the dogs outside.

A difficult thing I’m navigating now is that my dad was my last living relative who was really based in Barbados. Going home meant going to see dad. Now he’s gone. I think I’ve inherited this new responsibility, to kind of…

…be the ancestor, maybe?

Yes, exactly. I have to be that source of ancestral knowledge because I don’t want that connection to the island to be severed. It’s so important to me, and I think it’s really important to them. It’s who they are.

Well, not to add a burden, but if anyone is going to be able to communicate the story of family to your kids, it’s going to be you.

I guess that’s where the radical honesty comes in. Just saying, “There’s a lot that I don’t know. There’s a lot that’s been lost.” And: “Let’s forge a new relationship with this place together.” It’ll be exciting, but also bittersweet to step out into the airport arrivals hall and have to get a taxi when I used to see dad impatiently smoking a cigarette.

That must feel very heavy—wanting the connection to that place but facing that absence.

Sometimes, I think it would almost be easier, in some ways, to just never go back. But it’s necessary to confront that loss. I’ll figure out what I’m going to build in that space.